This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 2, "Long Journey Home: Folklife in the South." Find more from that issue here.

The music died when Elvis joined the Army. Or when Little Richard found religion. The music went down with Otis Redding’s plane — or was it Duane Allman’s motorcycle. It was betrayed when Gregg Allman turned state’s evidence against his roadie, or the day Phil Walden met Jimmy Carter ....

Rock music must periodically be pronounced dead to be rejuvenated. Southern rock, from which all rock derives, is a feisty form which has been killed off dozens of times in the last quarter-century or so. Yet no matter how often the critics or the social arbiters or concerned parents prepare the bier, the corpse keeps dancing back to life.

Though easily eulogized, it is less simple to determine the birth of Southern rock. The form’s immediate ancestors, country-western music and the blues, as endlessly explicated by various pundits, have been performed in the region since before the turn of the century. With the advent of the phonograph, and then the radio, these musics were widely disseminated. Country music was broadcast as early as 1922 on Atlanta’s WSB; by the time WSM aired the first Grand Ole Opry in 1935, the “hillbilly” sound was a national phenomenon. The blues, though broadcast less widely for racial reasons, were recorded earlier and more thoroughly than country; some artists recorded in the field around 1917, with dozens of labels like Okeh, Paramount and Vocalion making “race music” available throughout the country.

Wherever these musics fuse, one finds the idiosyncratic essence of Southern rock. In somewhat the same fashion that an atomic reaction begins when the unstable element reaches critical mass, thus did Southern rock explode when arbitrary color lines were crossed. Was country music the white man’s domain? The first country artist recorded in Nashville was a harmonica-playing shoeshine boy named Deford Bailey, who was a member of the Grand Ole Opry troupe decades before Charlie Pride was born. Could only black men authentically sing the blues? Along came Jimmie Rodgers, “The Singing Brakeman,” whose soulful singing was an inspiration for later bluesmen like Howlin’ Wolf.

Southern rock, then, is a fusion of energy and emotion from the musics of both races, a unique form each can share. As the music transcends social barriers, it becomes the object of authoritarian disapproval, then a rallying point for those who would resist authority. This music demands some sort of response: turn it up or turn it off, and be cognizant that either choice is charged with a kind of political significance.

Certainly, the first practitioners of Southern rock had no such rhetoric in mind when they created the form. Greil Marcus, in his book, Mystery Train, argues a persuasive case on behalf of Harmonica Frank Floyd’s claim to have been the first Southern rocker. A drifting street singer from Mississippi, Floyd was 43 in 1951 when he cut his first records for Sam Phillips in Memphis. In the years of rambling that preceded, the harmonica player had picked up musical mannerisms from black and white players alike. “People think I am a colored man,” he told one blues collector, “but I really am white.” His music, earthy country blues played at what came to be known as a rock tempo, had no particular color; it was a new sound altogether.

Sam Phillips was the man to see if one had a new sound in mind. At his small Memphis studio, Phillips recorded blues and country singers alike in search of one artist who would crack the complacent world of pop music wide open. His criteria were simple: “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars.” Though Harmonica Frank and others failed to connect with the public, Phillips did discover a man to fit his bill: Elvis Presley.

As the story goes, Elvis was driving a truck for Crown Electric in Memphis when he cut his first tentative sides in 1953. He was 18, with a squeaky baritone voice and little else in the way of musical talent. His demo sides were unexceptional, but Phillips’ secretary to press Phillips on Presley’s behalf. Phillips acceded, bringing in electric guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black to augment Presley’s acoustic guitar and vocals in a formal audition.

The combination clicked. On Monday, July 6, 1954, Elvis and two sidemen recorded the first of the great Southern rock singles. After experimenting unsuccessfully with some pop standards, Elvis suddenly swung into a fired-up arrangement of “That’s All Right (Mama),” a blues tune by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. Phillips missed the first take, but had his one-track tape recorder rolling when the trio tried the song again. The result was one minute and 54 seconds of the fusion Phillips had been looking for. It was extraordinary to hear the white boy sing so blackly; there was no minstrel distance from the emotions expressed. Perhaps the ease with which Elvis summoned up such anarchistic music scared Sam Phillips a little bit; all accounts of this epochal session describe the participants as being taken aback by their accomplishment.

If “That’s All Right” occurred spontaneously, then recording a complementary flip side for the single was a painstaking proposition. Bill Monroe’s bluegrass standard, “Blue Moon of Kentucky” was chosen as a change of pace, but Elvis transformed even the straight country arrangement, and the final product was an up-tempo groove that bore little resemblance to the original. Elvis crooned, shouted, and exhorted the sidemen to play fast and loud, and Phillips used an echoing recording technique to give an ominous edge to the proceedings.

Phillips took the finished tapes across town to Dewey Phillips (no kin), whose Red Hot & Blue program on WHBQ was one of the most popular shows in the area. Though the disc jockey usually played black blues exclusively, he decided to take a chance on Presley’s version of “That’s All Right,” playing it about 9:30 that evening. The station was immediately swamped with telephone response, callers who wanted to know who sang the song and when it would be played on the air again. Dewey Phillips repeated the tune seven times that night, and finally dispatched friends to find the singer and bring him to WHBQ for an interview. Elvis was found in a movie house and rushed to the station, where on the air he was acclaimed as a new sensation. As the Presley phenomenon began, rock began to roll.

Sam Phillips held onto Elvis for a mere 16 months before selling his contract to RCA, but the sides Elvis cut for Phillips’ Sun label may have been the best of his lengthy career. Those songs — collected on The Sun Sessions (RCA 1675) — capture not only the cultural components of the Southern rock fusion, but a sexual essence which no academic phrase can properly elaborate. Elvis was more than an exciting music-maker; with his long, brilliantined hair and sideburns, suggestively smoldering eyes, and a restlessness onstage that drove girls wild, he was an exciting visual personification of the new music. His video was as good as his audio.

Elvis retained a personal manager, one Colonel Tom Parker. The former Hadacol salesman recognized a hot property when he saw one, and took steps to insure that his client’s career would be more than a flash in the pan, steering Elvis from the risks of his fusion music toward a more acces- sible, less controversial pop sound. When Elvis left Sun, his records hit the top of the pop, country and rhythm-and-blues (R&B) charts, then subsequently dominated what came to be called the rock-and-roll charts from 1955 until he joined the Army. The rock records were released less often as Elvis’ softer, balladic entries consolidated his appeal among women, and the Southern rock days can be said to have ended for Elvis after he moved to RCA in 1955. Ironically, Sam Phillips made only $35,000 on the RCA deal, much less than the hoped-for billion.

In the wake of Elvis, other hopefuls came to Sun from all over the South. There were the Arkansas country boys, Johnny Cash and Charlie Rich, Roy Orbison from Texas, Carl Perkins from right there in Memphis, Jerry Lee Lewis from Faraday, Louisiana, and many more. Sam Phillips recorded them all, in the process capturing some of the most energized music ever made: songs like “I Walk The Line,” “Lonely Weekends,” “Ooby Dooby,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Whole Lotta Shakin”’ and “Great Balls of Fire.”

Each of these artists left Southern rock for country sooner or later, and only Jerry Lee Lewis kept coming back to rock some more. Lewis came to record at Sun soon after being fired from a church piano job for playing roadhouse riffs during hymns. All of Lewis’ recorded work seems tinged by hellfire, a Pentecostal rock whose good times are pervaded with a sense of certain damnation (or so, well into his cups, he once earnestly explained to this writer).

Though more loyal to the spirit of rock throughout his career than Elvis proved to be, Jerry Lee never surpassed Presley’s achievements. When Elvis went into the service, Jerry Lee might have assumed the throne but for a morals scandal that erupted during an English tour. The Britons raised a furor over Jerry Lee’s marriage to his 13-year-old cousin Myra, a stigma which effectively blackballed the rocker from the popular market for many years. The sense of frustration never completely left him. (Indeed, early in 1977, Jerry Lee was arrested outside Elvis’ mansion in Memphis allegedly drunk and waving a pistol, demanding a meeting with Presley).

Millions of postwar adolescents with time to kill and money to spend adopted the new rock-and-roll music as their own, despite (or because of) parental disapproval. Record companies across the nation hurried to board the bandwagon, competing among themselves to discover new recording stars. In the South, activity was widespread; Antoine “Fats” Domino, who had been a successful R&B artist for seven years, had a rock hit in 1956 with “I’m in Love Again,” the first of many Number One singles for the New Orleans singer.

Huey “Piano” Smith and the Clowns recorded in Jackson, Mississippi, for Johnny Vincent’s Ace label, and connected in 1957 with songs like “Rockin’ Pneumonia and The Boogie-Woogie Flu.”

From Macon, Georgia, came “Little Richard” Penniman, who often used Fats Domino’s sidemen to accompany nonsensical celebrations like “Tutti Frutti” and “Good Golly Miss Molly.”

Though Southern rock was popular with the youth of America, its acceptance was by no means universal throughout the South. The implications of black music being sung for white kids were not lost on certain white racist organizations, many of which attempted to have rock banned as a pernicious influence upon impressionable Caucasian kids. At least one such group cited the NAACP as the evil force behind rock-and-roll.

The ugly culmination of this cultural antagonism occurred in April, 1956, when six men leaped onstage at Municipal Auditorium in Birmingham during a performance by Nat “King” Cole. The intruders, one of whom was a member of a White Citizens Council, beat the singer, later claiming to have acted on behalf of a boycott of “bebop and Negro music.” Cole, one of the finest pop stylists of the time, belonged to neither category.

Record producers in the Northeast and West sought to cash in on the success of Elvis, Little Richard and the rest by releasing records that aped the mannerisms of Southern rock. Soon the charts were jammed with ersatz Elvis, and, to paraphrase an economic maxim, the bad music tended to drive out the good. By 1959, Elvis was in the Army, Jerry Lee was in disgrace, and Little Richard, having undergone a religious experience while aboard an airplane during an engine malfunction, had given up “sinful music” to sing in the Seventh Day Adventist Church. Southern rock had ceased to affect the teen audience as a national phenomenon.

Throughout the following lean years, Southern artists continued to appear upon the charts, but most were singing modified pop tunes, country or soul. The fusion of white and black which made Southern rock unique was dormant until the early ’60s.

In 1962, Booker T and the MGs revived it with a hit instrumental called “Green Onions.” Booker T. Jones was a keyboard player in the Stax Studio in Memphis, where he and the session players who made up the MGs (Memphis Group) backed up soul artists like Carla Thomas and Otis Redding. Few outside the industry knew that the bass player, Donald “Duck” Dunn, and the guitarist, Steve Cropper, were white, so well did their lyrical chops blend with the funk laid down by Jones and the drummer, Al Jackson. This time, the Southern rock fusion helped black singers cross over from the limited R&B market to the potentially lucrative rock market.

Berry Gordy’s Motown label in Detroit had crossed black artists over first with slick, rhythmic productions, but Southern crossover records emphasized a mellow, bass-dominated sound in which the rhythm guitar could become a lead instrument. Had Motown been less popular, and had the Beatleled British Invasion not begun in 1963, it is possible the widely-popular “Southern Groove” would have dominated the music of the decade. As it was, the Stax sound of the mid-’60s propelled artists like Sam & Dave, Wilson Pickett, Joe Tex and Otis Redding to the top of the rock charts, and it had a significant influence upon the British groups with whom it competed for public favor. Compare, for example, the Rolling Stones’ version of “Pain in My Heart” with Otis Redding’s original, or Otis’ version of “Satisfaction” with the Stones’.

Otis Redding is a pivotal figure in this movement. Born and raised in Macon, Otis made maximum use of his gospel training and his love for Little Richard’s music. His early recording efforts were unexceptional, but with the guidance of his manager, a college boy named Phil Walden, Redding learned to pace his headlong approach to a song; he could phrase fast and slow songs equally well. His first Stax release was “These Arms of Mine” in 1963, cut as an afterthought to a Johnny Jenkins session. Other hits followed: “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long,” “Respect,” and “Mr. Pitiful.” Redding learned to deliver a song in person as well as in a recording studio (Memphis DJ and Stax artist Rufus Thomas was instrumental in this process), while Walden devoted himself to breaking Otis out in the rock market. Redding was the only black artist on the bill at the landmark Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and undoubtedly would have become a national star of the first magnitude. However, a plane crash took the singer’s life early in 1968, and Otis Redding’s first Number One single, “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay,” was released posthumously.

Prior to that tragedy, a New York producer, Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler, had begun scouting the South for recording locations outside Memphis. The Stax musicians were undeniably great, and Wexler utilized their services on one hit after another, but he was dissatisfied with the working relationship he had with them. His search for a harmonious studio atmosphere ended in Florence, Alabama.

Rick Hall, a sometime session player and arranger, had established Fame Studios in his hometown, Florence, in 1961. His first big hit was Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On” the following year, and with the aid of Atlanta music publisher Bill Lowery, Hall produced a number of hit records thereafter for various labels. Unlike Stax, the session musicians at Fame were all white.

The first Number One record utilizing the “Muscle Shoals Sound” (a name perhaps derived from the fact that Florence had no airport, and producers and artists coming to the Fame Studios landed at Muscle Shoals) was Percy Sledge’s “When A Man Loves A Woman,” in 1966. It was a slow gospel wail cooking over a low funk burner, and it confirmed Jerry Wexler’s guess that Fame provided the environment he’d been looking for. In 1969, writing in Billboard, Wexler gave his view of the Southern rock fusion: “the musicians are Southern country people who sort of turned away from country music and toward the blues, which doesn’t mean they’ve abandoned country, but rather that they’ve turned from the tedium of the Nashville thing and into this more creative R&B thing, which stirs them. ”

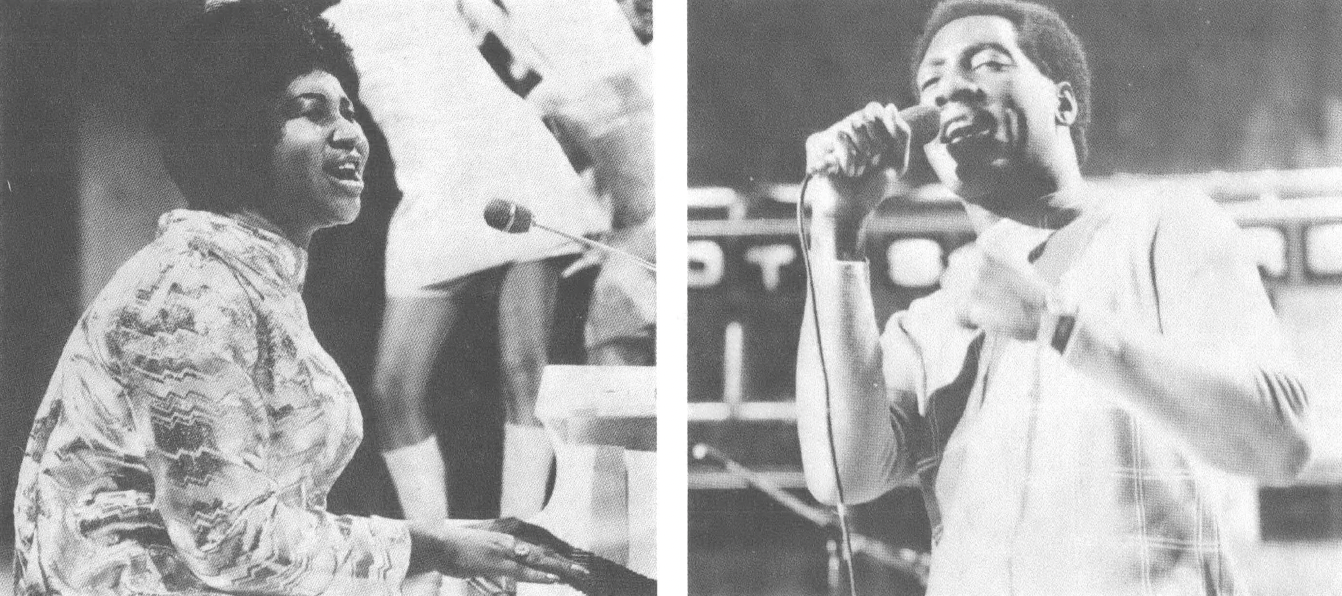

Wexler has written elsewhere that one of his greatest challenges as a producer was revitalizing Aretha Franklin’s career. Aretha was a gospel-pop singer from Detroit with an awesome potential untapped during her years at Columbia Records in the early ’60s. When Atlantic acquired her contract in 1967, Wexler gambled the reputation of his company on the Muscle Shoals musicians. Aretha was used to working with explicit musical charts and strict arrangements for her accompaniment, and Wexler could not be certain that she would be comfortable working in the loose, almost improvisatorial atmosphere to which the Fame session men were accustomed. As it turned out, the artist and the accompanists worked fluently together, and their first collaboration was one of the landmark records of modern music, “I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Loved You),” released in 1967. The record zoomed into the Top Ten, broke Aretha’s career wide open, and established the Muscle Shoals Sound as a viable entity within the music of the ’60s. That single, by the way, not only saved Atlantic Records’ reputation, but won producer Wexler several industry honors as Producer of the Year.

Because Rick Hall preferred to pay his musicians by the job instead of retaining them on salary, he lost many of his original session men. Some traveled to Memphis in late 1967 with guitarist Chips Moman to establish American Group Productions. Jerry Wexler urged New York musicians like the late saxophone wizard King Curtis to come South, where AGP helped English songstress Dusty Springfield create the best music of her career. Even Elvis Presley recognized the healing properties of the Southern Groove, using AGP facilities to record “Suspicious Minds” in 1968, a Number One single that did much to reestablish Elvis as the King of Rock.

Other former Fame sidemen set up shop in Muscle Shoals proper, establishing Quin Ivy Studios and Muscle Shoals Sound in 1969. The latter was staffed with what came to be regarded as the best studio band in America, informally known as the Swampers: Barry Beckett on keyboards, Jimmy Johnson on guitar, David Hood on bass, and Roger Hawkins on drums. These incomparable players have hosted sessions for virtually every notable in rock, from Bob Dylan to Paul Simon to the Rolling Stones, and at this writing show no signs of becoming jaded by success.

One Rick Hall find who did not start his own studio, but who came to be the major influence on latter-day Southern rock, was a lanky guitarist named Duane Allman. Duane and his brother, Gregg, a vocalist-keyboardist, came from Florida originally. While still teenagers, they scuffled in a series of short-lived bands with names like Allman Joys and the Hourglass until 1968, when the brothers split up — Gregg to seek a solo career and Duane to take his guitar prowess to the studios of Muscle Shoals.

Duane specialized in slide guitar, influenced by the playing of bottleneck guitarists like Elmore James. Unlike James, Allman played with a deft sense of melody, creating unique fills that made him popular at recording sessions, and eventually earned him the nickname “Skydog.” His work on Wilson Pickett’s cover version of “Hey Jude” came to the notice of the ubiquitous Jerry Wexler. It was Wexler who talked the late Otis Redding’s manager, Phil Walden, into putting a band together around Allman’s talents.

Walden created a label as well, founding Capricorn Records in Macon in 1969, with the debut album by the Allman Brothers Band as its first major release. The group Allman put together included his brother, who had given up the search for solo success to work once more with Duane, Richard “Dicky” Betts on second guitar, Berry Oakley to handle bass, and two drummers, Butch Trucks and Jai Johnny Johansen. This unusual configuration produced a refreshing new sound, relying as it did upon intricate twin lead guitars for soaring fills as a counterpoint to Gregg’s rough, blues-based vocals. Underneath that structure flowed the rhythm section, whose twin drums pushed but did not shove the music along. The formula was right. Whether reworking old standards like “Statesboro Blues” or exploring new areas of the Southern rock fusion, as in the jazz-influenced instrumental, “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” the Allman Brothers made music like nobody else in the world of post-psychedelic rock.

Employing the successful formula with which he managed Otis Redding, Phil Walden gradually built the Allman Brothers Band into a regional phenomenon. The band was totally unpretentious onstage — Duane once told an interviewer, “We don’t get paid to come out and dress up funny. We come to play.” Their espousal of exotic (to Southern youth) love-peace homilies left over from the halcyon days of hippiedom, and their unswerving allegiance to Southern culture created a fiercely loyal following for the band. Never before had a touring band in the South, an integrated band at that, drawn attention to the sense of brotherhood felt by kids growing up in the region. The Allman Brothers gave credence to their reputation for social awareness by playing free for assorted community benefits in the early days of their career. The band’s quasi-political activity, coupled with their admittedly superior musicianship, attracted the notice of trend-seeking rock journalists who helped boost the band into national prominence. Walden parlayed a grueling number of one-night stands into stints at the 1970 Newport Jazz Festival and Bill Graham’s rock palace, the Fillmore Auditorium. A double album recorded at the latter not only caught the spirit of their music at its peak, but also provided Capricorn and the Allman Brothers with their first gold record.

Then, as had happened to Walden with Otis Redding, tragedy struck as his client neared superstardom. In October, 1971, Duane Allman lost control of the motorcycle he was riding on a rainslicked Macon street and was killed almost instantly. The guitarist’s death saddened but did not sunder his band, who, practicing the brotherhood they preached, vowed to continue playing as a unit, as Duane would have wanted.

The band struggled to complete a new studio album, Eat A Peach, as a memorial to Duane. Incredibly, almost a year after Duane’s death, bassist Berry Oakley was killed in a similar motorcycle mishap. This time, the Allman Brothers Band rebounded from tragedy to record their most popular studio effort, Brothers and Sisters, from which “Rambling Man” became a Top Five single in 1973. That single, with its breezy highway lyric, propulsive rhythm and multi-tracked guitar lines, was hailed by many critics as the quintessential Southern rock single.

By this time, Southern rock was entrenched as a major trend in the otherwise directionless 1970s. The success of the Allmans’ fusion saw executives from every major record label flocking to the South to find more of the same. Shrewdly, Phil Walden had signed up aspiring groups some time earlier, so that, when the trend came his way, Walden was ensconced as the virtual czar of Southern rock. His Capricorn label was home for, besides the Allmans, a country-rock ensemble called the Marshall Tucker Band, bluesmen like Johnny Jenkins (whose album Ton-Ton Macoute remains one of the neglected classics of its kind), soul shouters like the Wet Willie Band, plus Cowboy, Captain Beyond, and more. Of these, only Wet Willie lived up to the promise of fusion, blending a roadhouse rhythm section with the black-white vocals of Jimmy Hall. Like the Allmans, Wet Willie had a compelling stage act, but their boisterous stage presence was completely unlike the low-key Allmans. It may be that Jimmy Hall’s inherent sexiness, like Elvis’ 20 years earlier, represented a threat to corporate status quo; for whatever reason, Walden never bothered to give the Wet Willie Band the build-up it deserved. After several disappointing years, the group left the Capricorn label altogether.

With his success, Phil Walden earned status in the business community, status that he attempted to translate into personal power. To that end, he cultivated the friendship of Georgia’s governor, Jimmy Carter, among other politicos, and that friendship proved beneficial to both. Early in the Carter push for the Presidency, Walden organized rock benefit concerts featuring Capricorn artists, the proceeds providing a crucial cash flow for the financially strapped campaign. At this writing, Walden participates less actively in the administration of his label, and it is rumored that he will make a run for political office in Georgia.

Under Walden’s absentee regime, and perhaps concurrent with the broadening of the label’s scope to include non-native talents like Elvin Bishop and comedian Martin Mull, Capricorn has not thrived. The label’s flagship group, the Allman Brothers, disintegrated for a number of reasons throughout 1975, and then, when Gregg Allman testified against his former road manager, Scooter Herring, in a widely publicized drug trial (during which it was revealed that Allman himself was a heavy drug user), the illusion of brotherhood was shattered for all time. Allman went on to a solo career seemingly no more successful than his first attempt in 1968; he became more famous as the husband of TV celebrity Cher Bono than as an accomplished musician.

Though no longer a dominant influence on the rock of the ’70s, the Southern Sound is kept alive by Allman Brothers derivations like Jacksonville, Florida’s Lynyrd Skynyrd band, or the Atlanta Rhythm Section, whose journeymen bid fair to pick up where the Allmans left off, with tunes like 1977’s hit “So Into You.”

Is the music dead once more? Will another such pronouncement bring the Southern rock fusion back to the forefront of the popular consciousness once again? Given the complacency of the current rock audience and its apparent willingness to listen to anything the radio plays regardless of its worth, it could well be that there is no place for the exuberance, the careless energy of Southern rock anymore.

And yet...this is the kind of complacency that Elvis Presley shattered the first time around, that an impatient Otis Redding stirred to life, that Duane Allman sought to turn on its ear. There is no shortage of the liberating energy of Southern rock; even now bearers of that peculiar force play their songs and raise their hell somewhere near you. Complacency is not safe while Southern rock is abroad in the land; ennui does not prosper. Let the fusion burn.

References

Of course, Southern rock must be heard to be fully comprehended. Obviously, it is hard to read words about the particular qualities of phonograph records and performing groups without experiencing them for yourself. So, do so. Several records can give you an especially good idea of what this fusion is all about. Besides Elvis Presley’s Sun Sessions mentioned earlier, you might listen to Elvis, Vol. 1: A Legendary Performer for a succinct survey of his career. Otis Redding records are hard to come by since the singer’s death, but a little judicious rummaging through local record stores should uncover an old Capricorn set called The History of Otis Redding. In the oldies bins you might be lucky enough to find a Stax issue called Dictionary of Soul; don’t let that pass you by.

There are plenty of Allman Brothers Band albums around, and if you never listened to them before — as I write this, I am earnestly convincing myself that somebody out there has not — procure Live at the Fillmore East for an idea of what all the brouhaha is about. And should you want to take a rapid trip through latter-day Southern rock, Capricorn Records has, obligingly, released an album called The South’s Greatest Hits, which isn’t entirely what the title intimates, but is a nice collection anyway.

If you insist on living your musical life vicariously through the writing of critics, you could do worse than the following selections:

Christgau, Robert, Any Old Way You Choose It. Baltimore, 1973.

Gillett, Charlie, The Sound of the City. New York, 1972.

___________, Making Tracks: Atlantic Records and the Growth of a Multi-Billion Dollar Industry. New York, 1974.

Hemphill, Paul, The Nashville Sound, New York, 1970.

Marcus, Greil, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock’n’Roll Music. New York, 1976.

Tags

Courtney Haden

At various times a television producer and radio station program direc tor, Courtney Haden currently edits Southern Style, a weekly cultural tabloid in Birmingham, where he also engineers at Boutwell Studios, producing rock groups and radio commercials alike. He makes his residence in Tuscaloosa as best he can. (1977)