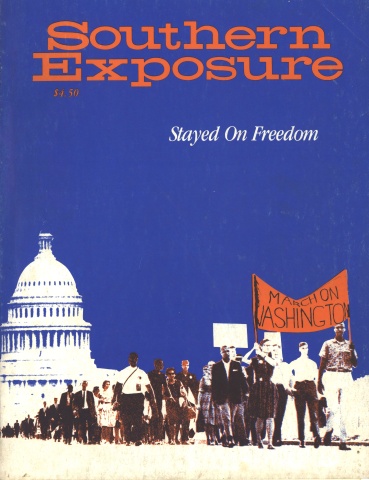

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

They say that Freedom is a constant sorrow,

They say that Freedom is a constant sorrow,

They say that Freedom is a constant sorrow,

Oh, Lord, we’ve struggled so long,

We must be free, we must be free.

(Freedom song composed by member of the Young family, Worth County, Georgia, 1966)

Media coverage has played an essential part in the planning and development of Movement organizations. At the local level, civil rights organizations are composed primarily of poor people whose only real resources are themselves. To make the most of themselves as resources, they rely heavily on events which highlight injustices and attract media attention.

Newspaper and television coverage in the ’60s by local Southern media was often biased toward the existing power structures and seldom adequate to the task of providing balanced and fair reporting of the civil-rights struggle. By and large editors and station owners were part and parcel of the segregated system. The media had the power to make events happen or not happen in the eyes of the public. When one radio station in Dawson, Georgia, claimed, “If you haven’t heard it on WDWD, it hasn’t happened,” there was more going on than just bragging rights for news coverage. News blackouts, distortion of facts, selective use of information were all important to the effort of local establishments to keep control of their communities by regulating the flow of information.

In this climate, it is no wonder that it was difficult to get the word out about voter-registration work, courtroom struggles, demonstrations and organizing. If groups attracted national media, people across the country would be more likely to know what was going on than folks in the next county.

In 1968 in southwest Georgia, there were 26 radio stations, one television station, one daily newspaper and a host of small-town local newspapers. Three established white families controlled half of the radio stations, and one man was both editor of the daily newspaper and owner of the television station. These families owned plantations and businesses, and participated on boards of organizations with vested interests in maintaining segregation and economic discrimination against blacks.

An example of outright distortion of news took place in the spring of 1968. Junior Nelson, a 17-year-old black youth, was shot to death by a white store clerk in the small town of Warwick, Georgia. According to a number of witnesses from the black community, Nelson had been trying to break up a fight between a friend of his and a Warwick police officer who had taunted the friend while arresting him for drinking a beer in public. The clerk came out of the store and struck Junior Nelson, knocking him down. When he angrily got back to his feet, the clerk shot him. Nelson lay for approximately half an hour on the street with a bullet wound in his abdomen, while a group of whites armed with guns encircled him letting no one, not even the boy’s mother, come to his aid. Eventually Junior Nelson was hauled off to the Worth County Hospital, not in an ambulance but in a police car, and he died. But the next day the local radio, television and newspapers carried the story that Junior Nelson had attacked the clerk with a knife, and the clerk had shot in self-defense.

The clerk was never arrested or indicted. The black community of Worth County organized a boycott of Griffin’s Grocery, where he worked. Fearing reprisals, so the story goes, the clerk mowed his yard with a shotgun in one hand. Eventually he moved away from Warwick. However, despite much clamor from the black community about the incident, the news media never looked further into the story of the shooting of Junior Nelson.

Distortion was only one way the local media made things difficult for blacks. Media also blacked out news — ignoring it altogether — or chose only to select certain sources of information. Such incomplete and imbalanced reporting is typified by the story of Dorothy Young and her family during their struggle with school desegregation in 1968 and 1969.

In the ’60s, the response of Southern states to the demands of the Brown v. Board of Education decision of the Supreme Court was the “freedom of choice” system. Under this system students were permitted to enroll at the school of their choice in their school district, provided that their choice did not increase segregation. The initiative to desegregate the schools was left with individual families, and the pressures against exercising this “freedom of choice” were enormous. As a result only a handful of black students enrolled at white schools, and virtually no white students enrolled in the black schools.

The few pioneer black families who dared to send their children to the better-funded and equipped white schools did so knowing that they were not welcome and that they would suffer daily abuses. These families tended to be landowners and farmers who did not have to fear losing their jobs or homes in reprisal for their activities.

One such family was that of Leroy and Ida Mae Young of Worth County, Georgia. The Young family had long been active in the Civil Rights Movement in the southwest Georgia area, working tirelessly in voter-registration drives and welfare rights organizing and providing support and encouragement for other families in the Movement throughout the county. They took the risk of housing fieldworkers from SNCC, the Southwest Georgia Project (a regional civil-rights resource organization) and other “outside agitators.” On their 150-acre farm they raised vegetables, hogs and chickens. Leroy’s two brothers, Sonny and James, had adjacent small farms and with the combined machinery and labor of three families they raised and marketed cotton, soy beans, peanuts, corn and other crops. Leroy also held a job with a fertilizer plant outside of Worth County.

The Youngs took the courageous step of sending their children to the white schools of Worth County. Fourteen-year- old Dorothy was among the first blacks to enroll at an all-white school in the county. She remembers the torrent of abuses suffered by her and the others who enrolled with her in the seventh grade of Warwick Elementary School:

The first year was real bad because there were only three of us in the school. They treated us terrible. They [white students] would kick you and hit on you. And the teachers were bad, too. We had one teacher when I was in the seventh grade that whenever we made a good grade on a test or something, she would show it before the whole class and say, “Before I would let them beat me I’d go to Pokimo and hide my head and never come up.”

On December 4, 1968, Dorothy and her younger sister Yvonne, age 11, were picked up from school by the deputy sheriff of Worth County and taken to the Albany Detention Home, the juvenile center in Dougherty County, 25 miles away.

I was walking down the hall to class and the principal called me to his office. So I went and he said to come go with him. I asked where we were going. He told me not to ask any questions, just come on! Then he grabbed me by the coat behind my neck and took me out to a car. He took my purse and searched it. I don’t know what he was looking for. And my little sister Yvonne was out there crying. I asked him where he was taking us and he said, “Shut up and don’t ask any questions. ” He didn’t tell us where we were going. We went to Albany. I didn’t know where we were but I found out we were in a juvenile home. I didn’t know why we were there, and I didn’t find out until I read it in the paper and heard it on the radio. We stayed there seven days.

Mr. and Mrs. Young did not learn of their daughters’ whereabouts until the following day when their attorney, C.B. King (then the only black lawyer in southwest Georgia), located them by phoning the Department of Health, Education and Welfare in Atlanta.

Dorothy and Yvonne were charged with “being in a state of delinquency.” Yvonne had come to the defense of her younger brother, who had been kicked in the shins by a white boy; Dorothy was accused of using “vile, obscene and profane language” without just cause. A white boy had been throwing spitballs at her and taunting her. She had told him to stop. The boy had called her “nigger,” and she had told him to “kiss my ass.” They were held in the detention home for seven days, during which their parents were not allowed to visit, and no bond was set. Judge Bowie Gray, who had signed the petition authorizing the arrests, refused to speak with an assistant to attorney King.

They locked me up in a room and wouldn’t let me talk to nobody. They said the less you say in here the better it will be for you. I thought I wasn’t never going to get out of there. They used to treat me like an old dog. They wouldn’t give me no covers [for the bed] at all. During the day they took the mattress away while I was locked up in the room. They didn’t want you laying in the bed. The FBI came to see me. They wouldn’t let nobody else come to see me, but they let the FBI. And they tried to trick me. They said, “Now, come on, you can tell us the truth. We’re not going to tell nobody. Didn’t you curse them little white girls out and beat that white boy up.” I said, “Does my lawyer know y ’all are here.” “Yeah, yeah, we have his permission.” I told them I didn’t believe it and they said I could still talk to them. “It is just between us and you. ’’But I wouldn’t talk to them.

After a hearing, Yvonne was released on probation, but Dorothy was sentenced to the state youth detention system for an undetermined sentence of anywhere between three months and six years. The case was appealed, but the judge would not allow Dorothy to go home either in the custody of her parents or on bail. Then her attorneys filed a writ of habeus corpus in state and federal courts to have Dorothy released. The habeus corpus appeal failed on the state level but was granted by the federal court, and after nearly three months Dorothy went home. The white youths involved were not punished in any way.

In the court ruling, U.S. District Judge Newell Edenfield said:

Here the minor child involved was adjudged a delinquent on a charge of having used vile, obscene and profane language. . . . An adult charged with similar misconduct, even a hardened criminal or the town drunk, could, at most, be guilty of only a misdemeanor and would be entitled to bond pending appeal. The court concludes that to say the very least there is sufficient merit. . . to require that bail pending appeal be allowed.

In a related incident on December 20, two weeks after Dorothy and Yvonne’s arrest, Leroy, Jr. —their 16-year-old brother — was arrested for shooting at a car with two young white “hunters” in it. The two had made a few passes at the Young home and had shot at it. No one was injured in the shootings.

During this three-month period, the black community of Sylvester and the surrounding Worth County was in an uproar. They saw the actions against Dorothy and her family as revenge on the part of the school officials and law enforcement authorities for the embarrassment caused them by the school desegregation efforts. The Worth County Improvement League held nightly meetings and planned and carried out marches and demonstrations protesting the arrests of Dorothy, Yvonne and Leroy, Jr. They demanded their release and black representation on the school board and local governing bodies. In the series of marches and protests, over 100 people, primarily youths, went to jail to dramatize the injustices.

As a result of these demonstrations and a school boycott, there was considerable coverage of the events by the news media. Reports were published in newspapers ranging from the local Sylvester and Albany papers to the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. The news articles began appearing only after the demonstrations started, some five days after Dorothy and Yvonne were arrested. It is quite conceivable that there would not have been any news coverage were it not for the demonstrations and the organizing work done by the Worth County Improvement League with the impetus of the fired-up high school students.

However, there was a considerable difference between the news coverage by the local papers, The Sylvester Local and the Albany Herald, and the coverage given by papers in Atlanta and New York.

“Chicken Dips Snuff!!”

The Albany Herald’s biased coverage of the Dorothy Young story may be logically derived from the editorial policy of the editor-publisher Of the paper, James H. Gray, Jr., the current mayor of Albany. Mayor Gray probably has had more influence over the mass media of southwest Georgia a than any other individual. Besides being the editor and publisher of the newspaper, Gray owns or, through Gray Communications, Inc., has controlling interest in WALB, the local NBC affiliate television station which is seen in all 20 counties of the southwest Georgia area, plus television stations in Florida, Arkansas and Louisiana. He recently had to give up control of Gray Cablevision in Albany as a result of anti-trust and FCC.

James Gray has long been known as an avowed segregationist, and his racist actions have left their stamp on Albany and the state of Georgia. In May of 1962, when it became evident that the Tift Park public swimming pool in Albany would be integrated, he bought it and reopened it for whites only. During the massive demonstrations and sit-ins in Albany in 1961 and 1962, the Herald made fun of events that were shaking the entire country. When 75 clergy from various parts of the country gathered in Albany to demonstrate their support of the many who had gone to jail to protest injustices to blacks, the Herald came out with headlines like: “Crowd Cheers As Cops Clap Clerical Crowd in Calaboose.” In a Newsweek article in September, 1962, Gray had this to say: “The racial problem in Albany has been overemphasized. It’s not a real story.” Commenting on the reliability of his newspaper, he said: “The Herald reflects the attitude of Albany. ... If the Herald says a chicken dips snuff, you can lift its leg and find a box of it there.” Gray was also selected by the “axhandle” governor Lester Maddox as the Georgia State Democratic Chairman for the 1968 election. He headed the Georgia delegation whose credentials were successfully challenged by Julian Bond and a “challenge delegation” over the issue of fair representation at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. When the challenge delegation was given the right to half of the seats allotted the Georgia delegation, Gray and Maddox walked out of the convention.

The Sylvester Local, a weekly publication, was closest to the scene. Although the events continued for seven weeks, only two articles appeared in the Local, and only one of them dealt directly with the demonstrations. The first ran over a month after the arrests of Dorothy and Yvonne and a full four weeks after the demonstrations and school boycott began. The front-page headline read: “Parents are Warned on School Absences,” and the article consisted of an interview with the superintendent of schools in which he expressed concern over the high rate of absentees, particularly among black students, and reminded parents that all children between the ages of seven and 16 were required by law to attend school. The remainder of the article elaborated on the background and qualifications of the new superintendent.

The next week the Local ran a front-page article with the headline “More Marchers Arrested in Defiance of Mayor’s Ban” and a subhead stating “Lawhorne [the mayor of Sylvester] Vows to Keep Order.” This article featured the mayor and the superintendent of schools stating how they were going to keep order in Sylvester. There was a reference made to reports that the Improvement League was “seeking for the 14-year-old Negro girl’s release,” and that the charges be dropped against her older brother “accused of shooting at two young hunters.”

The Local seemed to have disregarded the fact that when there is controversy or confrontation, there are at least two points of view to be considered. The Local never talked to Dorothy or her parents or any of the hundreds of students involved. They did not talk to the Worth County Improvement League even though the League’s office was only three blocks from their own. They even chose to ignore the arrival of prominent civil-rights leaders such as Ralph Abernathy of SCLC, Horace Tate (then president of the Georgia Teachers Education Association) and state senator Leroy Johnson.

The Albany Herald, southwest Georgia’s only daily newspaper, gave more extensive coverage of the events in Worth County: 14 articles in all, including two feature articles and a number of AP and UPI releases. Frontpage coverage was given twice with small headlines. Headlines such as the following appeared: “Worth County Schools Close,” “Negroes Arrested in Worth,” “Negro Student Boycott Appears Over in Worth.” This latter headline appeared a full month before the demonstrations actually wound down, about the time when the Herald ceased its coverage.

With one or two meager exceptions there were no references to the position of the Worth County black community, but even these were only alleged references picked up by the Herald from wire services. The Herald also relied almost exclusively on sources within the school system and law enforcement agencies of Worth County. In the seven articles printed by the Herald which were not AP or UPI releases, the sources mentioned in order of the frequency of their appearance were as follows: the Worth County Superintendent of Schools, “school officials,” Judge Bowie Gray, “authorities,” the Sylvester Police, Worth County Sheriff Hudson, Deputy Sheriff Prichard, “white leaders,” Sylvester Mayor Thomas Lawhorne and the Sylvester City Court Judge. There were no firsthand reports from the black community.

The Herald seemed preoccupied with the national news media’s presence on the scene in Sylvester. One feature article dismissed it three times:

Much of the current controversy concerns two Negro girls, the object of national press attention and the daughters of a family living near Warwick. The sisters, 14 and 11, have been termed chronic “troublemakers.”

The girls were subjects of publicity in the New York Times and the Washington Post, as well as both Atlanta daily newspapers. Worth Countians said the big-city newspaper reports were often distorted and much press criticism unjustified.

The Herald also quoted Judge Gray, who had sentenced Dorothy:

“Sensational publicity, untruths and half-truths have spread far and wide. . . . False accounts in some over-anxious newspapers as to what the facts are resulting in unfavorable publicity, school boycotts and demonstrations designed to create pressure will not accomplish anything for the correction and rehabilitation of these children. The court is not affected by such things whatsoever.”

Two Atlanta daily papers, the afternoon Journal and the morning Constitution, which publish a joint paper on Sundays, carried 17 articles between them on the Dorothy Young story. Besides wire stories, they published a number of feature stories and assigned staff writers to cover the events. The Atlanta papers had nine feature articles compared to the Herald's two. Five of these were printed on the first page, one with banner headlines. Articles had such headlines as, “Worth Negroes Urge Probes, Map Protests,” “19 Arrested in Worth School Protests,” “Negroes Chant for Release of Worth Girl,” and “U.S. Court Orders Worth Girl Freed.” The last item wasn’t even covered by the Herald.

Furthermore, the coverage was considerably more balanced, quoting Dorothy’s parents, representatives of the Worth County Improvement League and a number of state black leaders. C.B. King, Dorothy’s attorney, was quoted several times. He was referred to as “Albany Attorney, C.B. King” by the Constitution and Journal, whereas to the Herald he was invariably “Albany Negro Attorney. . . .” The demands of the Improvement League were stated several times alongside the statements by Worth County officials. The Atlanta papers reported that state senator Leroy Johnson and state representative Ben Brown intended to investigate the events. One article noted that school officials justified their failure to punish the white hecklers because Dorothy was involved in repeated incidents, but with different white students each time; the article went on to explain:

The Southern Regional Council in Atlanta reports that one school system operating under the freedom of choice plan had a rule that any student regardless of race will be expelled after four incidents. The SRC said that in this particular case white students teamed up in groups offour, each picking a fight with the same Negro on different days. After four fights, the Negro was expelled and whites had only one incident logged on their records.

Thus this February 12 article linked the Dorothy Young story to the problems of desegregation throughout the South.

Accounts also appeared in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, and although fewer in number, they went into greater depth. They described the home of the Youngs and the background of Dorothy’s parents. They highlighted the unreasonable nature of Dorothy’s and Yvonne’s arrest and linked it to the family’s participation in civil-rights activities. They reported the Youngs’ account of the shooting incident involving older brother Leroy. Ironically, the further away the publication was from the scene of the events, the more balanced was the reporting.

After her release, Dorothy Young returned home as something of a heroine. She flew home on a plane chartered by SCLC and was accompanied by Andrew Young and Ralph Abernathy, who made a speech to the black community assembled in Sylvester to welcome her home. T

oday, Dorothy lives in Birmingham with her husband Chico Rivera and their son Inyea. Another child is on the way. She worked for a while at a commercial bakery, where she became the shop steward of the union local and was instrumental in getting some changes in health conditions. She quit that job for a better-paying job in the coal mines. She took training courses in handling mining equipment and was hired, but only after filing a sex discrimination suit against the mining company.

Tags

Joe Pfister

Joe Pfister is a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies who sings and writes songs and gets people singing together in his “spare time.” (1986)

Joe Pfister, now on the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies, was a field worker for the Southwest Georgia Project from 1966 to 1976. (1982)

Joe Pfister was a field worker for the Southwest Georgia Project for Community Education from 1966 to 1976. He is currently a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies and an editor of Southern Exposure. (1981)