In Egypt Land

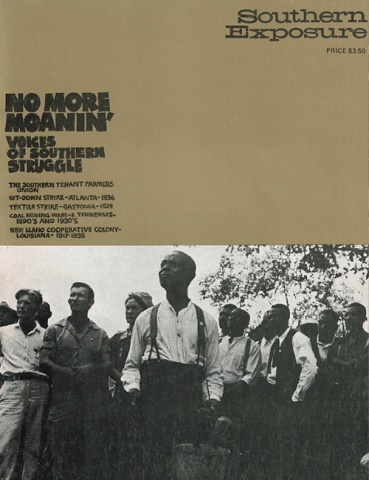

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 3/4, "No More Moanin'." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

“In Egypt Land” is taken from John Beecher’s To Live and Die in Dixie, 1966. Mr. Beecher has been active in popular struggles in the South all his live and published a number of other poetry books. His collected poems will appear in a single volume published by Macmillan in the Spring, 1974.

It was Alabama, 1932

but the spring came

same as it always had.

A man just couldn’t help believing

this would be a good year for him

when he saw redbud and dogwood everywhere in bloom

and the peachtree blossoming

all by itself

up against the gray boards of the cabin.

A man had to believe

so Cliff James hitched up his pair of old mules

and went out and plowed up the old land

the other man’s land but he plowed it

and when it was plowed it looked new again

the cotton and corn stalks turned under

the red clay shining with wet

under the sun.

Years ago

he thought he bought this land

borrowed the money to pay for it

from the furnish merchant in Notasulga

big white man named Mr Parker

but betwixt the interest and the bad times coming

Mr Parker had got the land back

and nigh on to $500 more owing to him

for interest seed fertilize and rations

with a mortgage on all the stock—

the two cows and their calves

the heifer and the pair of old mules—

Mr Parker could come drive them off the place any day

if he took a notion

and the law would back him.

Mighty few sharecroppers

black folks or white

ever got themselves stock like Cliff had

they didn’t have any cows

they plowed with the landlord’s mule and tools

they didn’t have a thing.

Took a heap of doing without

to get your own stock and your own tools

but he’d done it

and still that hadn’t made him satisfied.

The land he plowed

he wanted to be his.

Now all come of wanting his own land

he was back to where he started.

Any day

Mr Parker could run him off

drive away the mules the cows the heifer and the calves

to sell in town

take the wagon the plow tools the store-bought furniture and the shotgun

on the debt.

No

that was one thing Mr Parker never would get a hold of

not that shotgun . . .

Remembering that night last year

remembering the meeting

in the church he and his neighbors always went to

deep in the woods

and when the folks weren’t singing or praying or clapping and stomping

you could hear the branch splashing over rocks

right out behind.

That meeting night

the preacher prayed a prayer

for all the sharecroppers

white and black

asking the good Lord Jesus

to look down

and see how they were suffering.

“Five cent cotton Lord

and no way Lord for a man to come out.

Fifty cents a day Lord for working in tne field

just four bits Lord for a good strong hand

from dawn to dark Lord from can till can’t

ain’t no way Lord a man can come out.

They’s got to be a way Lord show us the way . . .”

And then they sang.

“Go Down Moses” was the song they sang

“Go down Moses, way down in Egypt land

Tell old Pharaoh to let my people go”

and when they had sung the song

the preacher got up and he said

“Brothers and sister

we got with us tonight

a colored lady teaches school in Birmingham

going to tell us about the Union

what’s got room for colored folks and white

what’s got room for all the folks

that ain’t got no land

that ain’t got no stock

that ain’t got no something to eat half the year

that ain’t got no shoes

that raises all the cotton

but can’t get none to wear

’cept old patchedy overhauls and floursack dresses.

Brothers and sisters

listen to this colored lady from Birmingham

who the Lord done sent I do believe

to show us the way . . .”

Then the colored lady from Birmingham

got up and she told them.

She told them how she was raised on a farm herself

a sharecrop farm near Demopolis

and walked six miles to a one-room school

and six miles back every day

till her people moved to Birmingham

where there was a high school for colored

and she went to it.

Then she worked in white folks’ houses

and saved what she made

to go to college.

She went to Tuskegee

and when she finished

got a job teaching school in Birmingham

but she never could forget

the people she was raised with

the sharecrop farmers

and how they had to live.

No

all the time she was teaching school

she thought about them

what could she do for them

and what they could do for themselves.

Then one day

somebody told her about the Union . . .

If everybody joined the Union she said

a good strong hand would get what he was worth

a dollar (Amen sister)

instead of fifty cents a day.

At settling time the cropper could take his cotton to the gin

and get his own fair half and the cotton seed

instead of the landlord hauling it off and cheating on the weight

“All you made was four bales Jim” when it really was six

(Ain’t it God’s truth?)

and the Union would get everybody the right to have a garden spot

not just cotton crowded up to the house

and the Union would see the children got a schoolbus

like the white children rode in every day

and didn’t have to walk twelve miles.

That was the thing

the children getting to school

(Amen)

the children learning something besides chop cotton and pick it

(Yes)

the children learning how to read and write

(Amen)

the children knowing how to figure

so the landlord wouldn’t be the only one

could keep accounts

(Preach the Word sister).

Then the door banging open against the wall

and the Laws in their lace boots

the High Sheriff himself

with his deputies behind him.

Folks scrambling to get away

out the windows and door

and the Laws’ fists going clunk clunk clunk

on all the men’s and women’s faces they could reach

and when everybody was out and running

the pistols going off behind them.

Next meeting night

the men that had them brought shotguns to church

and the High Sheriff got a charge of birdshot in his body

when Ralph Gray with just his single barrel

stopped a car full of Laws

on the road to the church

and shot it out with their 44’s.

Ralph Gray died

but the people in the church

all got away alive.

II

The crop was laid by.

From now till picking time

only the hot sun worked

ripening the bolls

and men rested after the plowing and plowing

women rested

little boys rested

and little girls rested

after the chopping and chopping with their hoes.

Now the cotton was big.

Now the cotton could take care of itself from the weeds

while the August sun worked

ripening the bolls.

Cliff James couldn’t remember ever making a better crop

on that old red land

he’d seen so much of

wash down the gullieS toward the Tallapoosa

since he’d first put a plow to it.

Never a better crop

but it had taken the fertilize

and it had taken work

fighting the weeds

fighting the weevils . . .

Ten bales it looked like it would make

ten good bales when it was picked

a thousand dollars worth of cotton once

enough to pay out on seed and fertilize and furnish for the season

and the interest and something down

on the land

new shoes for the family to go to church in

work shirts and overalls for the man and boys

a bolt of calico for the woman and girls

and a little cash money for Christmas.

Now though

ten bales of cotton

didn’t bring what three used to.

Two hundred and fifty dollars was about what his share of this year’s crop would bring

at five cents a pound

not even enough to pay out on seed and fertilize and furnish for the season

let alone the interest on the land Mr Parker was asking for

and $80 more on the back debt owing to him.

Mr Parker had cut his groceries off at the commissary last month

and there had been empty bellies in Cliff James’ house

with just cornbread buttermilk and greens to eat.

If he killed a calf to feed his family

Mr Parker could send him to the chain-gang

for slaughtering mortgaged stock.

Come settling time this fall

Mr Parker was going to get every last thing

every dime of the cotton money

the corn

the mules

the cattle

and the law would back him.

Cliff James wondered

why had he plowed the land in the spring

why had he worked and worked his crop

his wife and children alongside him in the field

and now pretty soon

they would all be going out again

dragging their long sacks

bending double in the hot sun

picking Mr Parker’s cotton for him.

Sitting on the stoop of his cabin

with his legs hanging over the rotten board edges

Cliff James looked across his fields of thick green cotton

to the woods beyond

and a thunderhead piled high in the south

piled soft and white like cotton on the stoop

like a big day’s pick

waiting for the wagon

to come haul it to the gin.

On the other side of those woods

was John McMullen’s place

and over yonder just east of the woods

Ned Cobb’s and beyond the rise of ground

Milo Bentley lived that was the only new man

to move into the Reeltown section that season.

Milo just drifted in from Detroit

because his work gave out up there

and a man had to feed his family

so he came back to the farm

thinking things were like they used to be

but he was finding out different.

Yes

everybody was finding out different

Cliff and John and Ned and Milo and Judson Simpson across the creek

even white croppers like Mr Sam and his brother Mr Bill

they were finding out.

It wasn’t many years ago Mr Sam’s children

would chunk at Cliff James’ children

on their way home from school

and split little Cliff’s head open with a rock once

because his daddy was getting too uppity

buying himself a farm.

Last time they had a Union meeting though at Milo Bentley’s place

who should show up but Mr Sam and Mr Bill

and asked was it only for colored

or could white folks join

because something just had to be done

about the way things were.

When Cliff told them

it was for all the poor farmers

that wanted to stick together

they paid their nickel to sign up

and their two cents each for first month’s dues

and they said they would try to get

more white folks in

because white men and black

were getting beat with the same stick these days.

Things looked worse than they ever had in all his time of life

Cliff James thought

but they looked better too

they looked better than they ever had in all his time of life

when a sharecropper like Ralph Gray

not drunk but cold sober

would stand off the High Sheriff with birdshot

and get himself plugged with 44’s

just so the others at the meeting could get away

and after that the mob hunting for who started the Union

beating men and women up with pistol butts and bull whips

throwing them in jail and beating them up more

but still not stopping it

the Union going on

more people signing up

more and more every week

meeting in houses on the quiet

nobody giving it away

and now white folks coming in too.

Cliff James looked over his ripening cotton to the woods

and above the trees the thunderhead piled still higher in

the south

white like a pile of cotton on the stoop

piling up higher and higher

coming out of the south

bringing storm . . .

III

"You”

Cliff James said

"nor the High Sheriff

nor all his deputies

is gonna git them mules.”

The head deputy put the writ of attachment back in his inside pocket

then his hand went to the butt of his pistol

but he didn’t pull it.

"I’m going to get the High Sheriff and help”

he said

"and come back and kill you all in a pile.”

Cliff James and Ned Cobb watched the deputy whirl the car around

and speed down the rough mud road.

He took the turn skidding

and was gone.

"He’ll be back in a hour” Cliff James said

“if’n he don’t wreck hisseff.”

"Where you fixin’ to go?” Ned Cobb asked him.

"I’s fixin’ to stay right where I is.”

“I’ll go git the others then.”

“No need of eve’ybody gittin’ kilt” Cliff James said.

"Better gittin’ kilt quick

than perishin' slow like we been a’doin’” and Ned Cobb was gone

cutting across the wet red field full of dead cotton plants

and then he was in the woods

bare now except for the few green pines

and though Cliff couldn’t see him

he could see him in his mind

calling out John McMullen and telling him about it

then cutting off east to Milo Bentley’s

crossing the creek on the foot-log to Judson Simpson’s . . .

Cliff couldn’t see him

going to Mr Sam or Mr Bill about it

no

this was something you couldn’t expect white folks to get in on

even white folks in your Union.

There came John McMullen out of the woods

toting that old musket of his.

He said it went back to Civil War days

and it looked it

but John could really knock a squirrel off a limb

or get a running rabbit with it.

“Here I is,” John said

and “What you doin’ ’bout you folks?”

“What folks?”

“The ones belongin’ to you.

You chillens and you wife.”

“I disremembered ’em,” Cliff James aid.

“I done clean disremembered all about my chillens and my wife.”

“They can stay with mine,” John said.

“We ain’t gonna want no womenfolks nor chillens

not here we ain’t.”

Cliff James watched his family going across the field

the five backs going away from him

in the wet red clay among the dead cotton plants

and soon they would be in the woods

his wife

young Cliff

the two girls

and the small boy . . .

They would just have to get along

best way they could

because a man had to do

what he had to do

and if he kept thinking about the folks belonging to him

he couldn’t do it

and then he wouldn’t be any good to them

or himself either.

There they went into the woods

the folks belonging to him gone

gone for good

and they not knowing it

but he knowing it

yes God

he knowing it well.

When the head deputy got back

with three more deputies for help

but not the High Sheriff

there were forty men in Cliff James’ cabin

all armed.

The head deputy and the others got out of the car

and started up the slope toward the cabin.

Behind the dark windows

the men they didn't know were there

sighted their guns.

Then the deputies stopped.

“You Cliff James!” the head deputy shouted

“come on out

we want to talk with you.”

No answer from inside.

“Come on out Cliff

we got something we want to talk over.”

Maybe they really did have something to talk over

Cliff James thought

maybe all those men inside

wouldn’t have to die for him or he for them . . .

“I’s goin’ out,” he said.

“No you ain’t,” Ned Cobb said.

“Yes 1 is,” Cliff James said

and leaning his shotgun against the wall

he opened the door just a wide enough crack

for himself to get through

but Ned Cobb crowded in behind him

and came out too

without his gun

and shut the door.

Together they walked toward the Laws.

When they were halfway Cliff James stopped

and Ned stopped with him

and Cliff called out to the Laws

“I’s ready to listen white folks.”

“This is what we got to say nigger!”

and the head deputy whipped out his pistol.

The first shot got Ned

and the next two got Cliff in the back

as he was dragging Ned to the cabin.

When they were in the shooting started from inside

everybody crowding up to the windows

with their old shotguns and muskets

not minding the pistol bullets from the Laws.

Of a sudden John McMullen

broke out of the door

meaning to make a run for his house

and tell his and Cliff James’ folks

to get a long way away

but a bullet got him in the head

and he fell on his face

among the dead cotton plants

and his life’s blood soaked into the old red land.

The room was full of powder smoke and men groaning

that had caught pistol bullets

but not Cliff James.

He lay in the corner quiet

feeling the blood run down his back and legs

but when somebody shouted

“The Laws is runnin’ away!”

he got to his feet and went to the door and opened it.

Sure enough three of the Laws

were helping the fourth one into the car

but it wasn’t the head deputy.

There by the door-post was John McMullen’s old musket

where he’d left it when he ran out and got killed.

Cliff picked it up and saw it was still loaded.

He raised it and steadied it against the door-post

aiming it at where the head deputy would be sitting

to drive the car.

Cliff only wished

he could shoot that thing like John McMullen . . .

IV

He didn’t know there was such a place in all Alabama

just for colored.

They put him in a room to himself

with a white bed and white sheets

and the black nurse put a white gown on his black body

after she washed off the dried black blood.

Then the black doctor came

and looked at the pistol bullet holes in his back

and put white bandages on

and stuck a long needle in his arm

and went away.

How long ago was it

he stayed and shot it out with the Laws?

Seemed like a long time

but come to think of it

he hid out in Mr Sam’s corn crib

till the sun went down that evening

then walked and walked all the night-time

and when it started to get light he saw a cabin

with smoke coming out the chimney

but the woman wouldn’t let him in to get warm

so he went on in the woods and lay down

under an old gum tree and covered himself with leaves

and when he woke it was nearly night-time again

and there were six buzzards perched in the old gum tree

watching him . . .

Then he got up and shooed the buzzards away

and walked all the second night-time

and just as it was getting light

he was here

and this was Tuskegee

where the Laws couldn’t find him

but John McMullen was dead in the cotton field

and the buzzards would be. at him by now

if nobody hadn’t buried him

and who would there be to bury him

with everybody shot or run away or hiding?

In a couple of days it was going to be Christmas

yes Christmas

and nobody belonging to Cliff James

was going to get a thing

not so much as an orange or a candy stick

for the littlest boy.

What kind of a Christmas was that

when a man didn’t even have a few nickels

to get his children some oranges and candy sticks

what kind of a Christmas and what kind of a country anyway

when you made ten bales of cotton

five thousand pounds of cotton

with your own hands

and you wife’s hands

and all your children’s hands

and then the Laws came to take your mules away

and drive your cows to sell in town

and your calves

and your heifer

and you couldn’t even get commissary credit

for coffee molasses and sow-belly

and nobody in your house had shoes to wear

or any kind of fitting Sunday clothes

and no Christmas for nobody . . .

“Go Down Moses” was the song they sang

and when they had finished singing

it was so quiet in the church

you could hear the branch splashing over rocks

right out behind.

Then the preacher got up and he preached . . .

“And there was a man what fought to save us all

he wrapped an old quilt around him

because it was wintertime and he had two pistol bullets in his back

and he went out of his house

and he started walking across the country to Tuskegee.

He got mighty cold

and his bare feet pained him

and his back like to killed him

and he thought

here is a cabin with smoke coming out the chimley

and they will let me in to the fire

because they are just poor folks like me

and when I have got warm

I will be on my way to Tuskegee

but the woman was afeared

and barred the door again him

and he went and piled leaves over him in the woods

waiting for the night-time

and six buzzards settled in an old gum tree

watching did he still breathe . . .”

The Sheriff removed Cliff James from the hospital to the country jail on December 22. A mob gathered to lynch the prisoner on Christmas day. For protection he was taken to jail in Montgomery. Here Cliff James died on the stone floor of his cell, December 27, 1932.

“In Egypt Land” is taken from John Beecher’s To Live and Die in Dixie, 1966. Mr. Beecher has been active in popular struggles in the South all his live and published a number of other poetry books. His collected poems will appear in a single volume published by Macmillan in the Spring, 1974.

It was Alabama, 1932

but the spring came

same as it always had.

A man just couldn’t help believing

this would be a good year for him

when he saw redbud and dogwood everywhere in bloom

and the peachtree blossoming

all by itself

up against the gray boards of the cabin.

A man had to believe

so Cliff James hitched up his pair of old mules

and went out and plowed up the old land

the other man’s land but he plowed it

and when it was plowed it looked new again

the cotton and corn stalks turned under

the red clay shining with wet

under the sun.

Years ago

he thought he bought this land

borrowed the money to pay for it

from the furnish merchant in Notasulga

big white man named Mr Parker

but betwixt the interest and the bad times coming

Mr Parker had got the land back

and nigh on to $500 more owing to him

for interest seed fertilize and rations

with a mortgage on all the stock—

the two cows and their calves

the heifer and the pair of old mules—

Mr Parker could come drive them off the place any day

if he took a notion

and the law would back him.

Mighty few sharecroppers

black folks or white

ever got themselves stock like Cliff had

they didn’t have any cows

they plowed with the landlord’s mule and tools

they didn’t have a thing.

Took a heap of doing without

to get your own stock and your own tools

but he’d done it

and still that hadn’t made him satisfied.

The land he plowed

he wanted to be his.

Now all come of wanting his own land

he was back to where he started.

Any day

Mr Parker could run him off

drive away the mules the cows the heifer and the calves

to sell in town

take the wagon the plow tools the store-bought furniture and the shotgun

on the debt.

No

that was one thing Mr Parker never would get a hold of

not that shotgun . . .

Remembering that night last year

remembering the meeting

in the church he and his neighbors always went to

deep in the woods

and when the folks weren’t singing or praying or clapping and stomping

you could hear the branch splashing over rocks

right out behind.

That meeting night

the preacher prayed a prayer

for all the sharecroppers

white and black

asking the good Lord Jesus

to look down

and see how they were suffering.

“Five cent cotton Lord

and no way Lord for a man to come out.

Fifty cents a day Lord for working in tne field

just four bits Lord for a good strong hand

from dawn to dark Lord from can till can’t

ain’t no way Lord a man can come out.

They’s got to be a way Lord show us the way . . .”

And then they sang.

“Go Down Moses” was the song they sang

“Go down Moses, way down in Egypt land

Tell old Pharaoh to let my people go”

and when they had sung the song

the preacher got up and he said

“Brothers and sister

we got with us tonight

a colored lady teaches school in Birmingham

going to tell us about the Union

what’s got room for colored folks and white

what’s got room for all the folks

that ain’t got no land

that ain’t got no stock

that ain’t got no something to eat half the year

that ain’t got no shoes

that raises all the cotton

but can’t get none to wear

’cept old patchedy overhauls and floursack dresses.

Brothers and sisters

listen to this colored lady from Birmingham

who the Lord done sent I do believe

to show us the way . . .”

Then the colored lady from Birmingham

got up and she told them.

She told them how she was raised on a farm herself

a sharecrop farm near Demopolis

and walked six miles to a one-room school

and six miles back every day

till her people moved to Birmingham

where there was a high school for colored

and she went to it.

Then she worked in white folks’ houses

and saved what she made

to go to college.

She went to Tuskegee

and when she finished

got a job teaching school in Birmingham

but she never could forget

the people she was raised with

the sharecrop farmers

and how they had to live.

No

all the time she was teaching school

she thought about them

what could she do for them

and what they could do for themselves.

Then one day

somebody told her about the Union . . .

If everybody joined the Union she said

a good strong hand would get what he was worth

a dollar (Amen sister)

instead of fifty cents a day.

At settling time the cropper could take his cotton to the gin

and get his own fair half and the cotton seed

instead of the landlord hauling it off and cheating on the weight

“All you made was four bales Jim” when it really was six

(Ain’t it God’s truth?)

and the Union would get everybody the right to have a garden spot

not just cotton crowded up to the house

and the Union would see the children got a schoolbus

like the white children rode in every day

and didn’t have to walk twelve miles.

That was the thing

the children getting to school

(Amen)

the children learning something besides chop cotton and pick it

(Yes)

the children learning how to read and write

(Amen)

the children knowing how to figure

so the landlord wouldn’t be the only one

could keep accounts

(Preach the Word sister).

Then the door banging open against the wall

and the Laws in their lace boots

the High Sheriff himself

with his deputies behind him.

Folks scrambling to get away

out the windows and door

and the Laws’ fists going clunk clunk clunk

on all the men’s and women’s faces they could reach

and when everybody was out and running

the pistols going off behind them.

Next meeting night

the men that had them brought shotguns to church

and the High Sheriff got a charge of birdshot in his body

when Ralph Gray with just his single barrel

stopped a car full of Laws

on the road to the church

and shot it out with their 44’s.

Ralph Gray died

but the people in the church

all got away alive.

II

The crop was laid by.

From now till picking time

only the hot sun worked

ripening the bolls

and men rested after the plowing and plowing

women rested

little boys rested

and little girls rested

after the chopping and chopping with their hoes.

Now the cotton was big.

Now the cotton could take care of itself from the weeds

while the August sun worked

ripening the bolls.

Cliff James couldn’t remember ever making a better crop

on that old red land

he’d seen so much of

wash down the gullieS toward the Tallapoosa

since he’d first put a plow to it.

Never a better crop

but it had taken the fertilize

and it had taken work

fighting the weeds

fighting the weevils . . .

Ten bales it looked like it would make

ten good bales when it was picked

a thousand dollars worth of cotton once

enough to pay out on seed and fertilize and furnish for the season

and the interest and something down

on the land

new shoes for the family to go to church in

work shirts and overalls for the man and boys

a bolt of calico for the woman and girls

and a little cash money for Christmas.

Now though

ten bales of cotton

didn’t bring what three used to.

Two hundred and fifty dollars was about what his share of this year’s crop would bring

at five cents a pound

not even enough to pay out on seed and fertilize and furnish for the season

let alone the interest on the land Mr Parker was asking for

and $80 more on the back debt owing to him.

Mr Parker had cut his groceries off at the commissary last month

and there had been empty bellies in Cliff James’ house

with just cornbread buttermilk and greens to eat.

If he killed a calf to feed his family

Mr Parker could send him to the chain-gang

for slaughtering mortgaged stock.

Come settling time this fall

Mr Parker was going to get every last thing

every dime of the cotton money

the corn

the mules

the cattle

and the law would back him.

Cliff James wondered

why had he plowed the land in the spring

why had he worked and worked his crop

his wife and children alongside him in the field

and now pretty soon

they would all be going out again

dragging their long sacks

bending double in the hot sun

picking Mr Parker’s cotton for him.

Sitting on the stoop of his cabin

with his legs hanging over the rotten board edges

Cliff James looked across his fields of thick green cotton

to the woods beyond

and a thunderhead piled high in the south

piled soft and white like cotton on the stoop

like a big day’s pick

waiting for the wagon

to come haul it to the gin.

On the other side of those woods

was John McMullen’s place

and over yonder just east of the woods

Ned Cobb’s and beyond the rise of ground

Milo Bentley lived that was the only new man

to move into the Reeltown section that season.

Milo just drifted in from Detroit

because his work gave out up there

and a man had to feed his family

so he came back to the farm

thinking things were like they used to be

but he was finding out different.

Yes

everybody was finding out different

Cliff and John and Ned and Milo and Judson Simpson across the creek

even white croppers like Mr Sam and his brother Mr Bill

they were finding out.

It wasn’t many years ago Mr Sam’s children

would chunk at Cliff James’ children

on their way home from school

and split little Cliff’s head open with a rock once

because his daddy was getting too uppity

buying himself a farm.

Last time they had a Union meeting though at Milo Bentley’s place

who should show up but Mr Sam and Mr Bill

and asked was it only for colored

or could white folks join

because something just had to be done

about the way things were.

When Cliff told them

it was for all the poor farmers

that wanted to stick together

they paid their nickel to sign up

and their two cents each for first month’s dues

and they said they would try to get

more white folks in

because white men and black

were getting beat with the same stick these days.

Things looked worse than they ever had in all his time of life

Cliff James thought

but they looked better too

they looked better than they ever had in all his time of life

when a sharecropper like Ralph Gray

not drunk but cold sober

would stand off the High Sheriff with birdshot

and get himself plugged with 44’s

just so the others at the meeting could get away

and after that the mob hunting for who started the Union

beating men and women up with pistol butts and bull whips

throwing them in jail and beating them up more

but still not stopping it

the Union going on

more people signing up

more and more every week

meeting in houses on the quiet

nobody giving it away

and now white folks coming in too.

Cliff James looked over his ripening cotton to the woods

and above the trees the thunderhead piled still higher in

the south

white like a pile of cotton on the stoop

piling up higher and higher

coming out of the south

bringing storm . . .

III

"You”

Cliff James said

"nor the High Sheriff

nor all his deputies

is gonna git them mules.”

The head deputy put the writ of attachment back in his inside pocket

then his hand went to the butt of his pistol

but he didn’t pull it.

"I’m going to get the High Sheriff and help”

he said

"and come back and kill you all in a pile.”

Cliff James and Ned Cobb watched the deputy whirl the car around

and speed down the rough mud road.

He took the turn skidding

and was gone.

"He’ll be back in a hour” Cliff James said

“if’n he don’t wreck hisseff.”

"Where you fixin’ to go?” Ned Cobb asked him.

"I’s fixin’ to stay right where I is.”

“I’ll go git the others then.”

“No need of eve’ybody gittin’ kilt” Cliff James said.

"Better gittin’ kilt quick

than perishin' slow like we been a’doin’” and Ned Cobb was gone

cutting across the wet red field full of dead cotton plants

and then he was in the woods

bare now except for the few green pines

and though Cliff couldn’t see him

he could see him in his mind

calling out John McMullen and telling him about it

then cutting off east to Milo Bentley’s

crossing the creek on the foot-log to Judson Simpson’s . . .

Cliff couldn’t see him

going to Mr Sam or Mr Bill about it

no

this was something you couldn’t expect white folks to get in on

even white folks in your Union.

There came John McMullen out of the woods

toting that old musket of his.

He said it went back to Civil War days

and it looked it

but John could really knock a squirrel off a limb

or get a running rabbit with it.

“Here I is,” John said

and “What you doin’ ’bout you folks?”

“What folks?”

“The ones belongin’ to you.

You chillens and you wife.”

“I disremembered ’em,” Cliff James aid.

“I done clean disremembered all about my chillens and my wife.”

“They can stay with mine,” John said.

“We ain’t gonna want no womenfolks nor chillens

not here we ain’t.”

Cliff James watched his family going across the field

the five backs going away from him

in the wet red clay among the dead cotton plants

and soon they would be in the woods

his wife

young Cliff

the two girls

and the small boy . . .

They would just have to get along

best way they could

because a man had to do

what he had to do

and if he kept thinking about the folks belonging to him

he couldn’t do it

and then he wouldn’t be any good to them

or himself either.

There they went into the woods

the folks belonging to him gone

gone for good

and they not knowing it

but he knowing it

yes God

he knowing it well.

When the head deputy got back

with three more deputies for help

but not the High Sheriff

there were forty men in Cliff James’ cabin

all armed.

The head deputy and the others got out of the car

and started up the slope toward the cabin.

Behind the dark windows

the men they didn't know were there

sighted their guns.

Then the deputies stopped.

“You Cliff James!” the head deputy shouted

“come on out

we want to talk with you.”

No answer from inside.

“Come on out Cliff

we got something we want to talk over.”

Maybe they really did have something to talk over

Cliff James thought

maybe all those men inside

wouldn’t have to die for him or he for them . . .

“I’s goin’ out,” he said.

“No you ain’t,” Ned Cobb said.

“Yes 1 is,” Cliff James said

and leaning his shotgun against the wall

he opened the door just a wide enough crack

for himself to get through

but Ned Cobb crowded in behind him

and came out too

without his gun

and shut the door.

Together they walked toward the Laws.

When they were halfway Cliff James stopped

and Ned stopped with him

and Cliff called out to the Laws

“I’s ready to listen white folks.”

“This is what we got to say nigger!”

and the head deputy whipped out his pistol.

The first shot got Ned

and the next two got Cliff in the back

as he was dragging Ned to the cabin.

When they were in the shooting started from inside

everybody crowding up to the windows

with their old shotguns and muskets

not minding the pistol bullets from the Laws.

Of a sudden John McMullen

broke out of the door

meaning to make a run for his house

and tell his and Cliff James’ folks

to get a long way away

but a bullet got him in the head

and he fell on his face

among the dead cotton plants

and his life’s blood soaked into the old red land.

The room was full of powder smoke and men groaning

that had caught pistol bullets

but not Cliff James.

He lay in the corner quiet

feeling the blood run down his back and legs

but when somebody shouted

“The Laws is runnin’ away!”

he got to his feet and went to the door and opened it.

Sure enough three of the Laws

were helping the fourth one into the car

but it wasn’t the head deputy.

There by the door-post was John McMullen’s old musket

where he’d left it when he ran out and got killed.

Cliff picked it up and saw it was still loaded.

He raised it and steadied it against the door-post

aiming it at where the head deputy would be sitting

to drive the car.

Cliff only wished

he could shoot that thing like John McMullen . . .

IV

He didn’t know there was such a place in all Alabama

just for colored.

They put him in a room to himself

with a white bed and white sheets

and the black nurse put a white gown on his black body

after she washed off the dried black blood.

Then the black doctor came

and looked at the pistol bullet holes in his back

and put white bandages on

and stuck a long needle in his arm

and went away.

How long ago was it

he stayed and shot it out with the Laws?

Seemed like a long time

but come to think of it

he hid out in Mr Sam’s corn crib

till the sun went down that evening

then walked and walked all the night-time

and when it started to get light he saw a cabin

with smoke coming out the chimney

but the woman wouldn’t let him in to get warm

so he went on in the woods and lay down

under an old gum tree and covered himself with leaves

and when he woke it was nearly night-time again

and there were six buzzards perched in the old gum tree

watching him . . .

Then he got up and shooed the buzzards away

and walked all the second night-time

and just as it was getting light

he was here

and this was Tuskegee

where the Laws couldn’t find him

but John McMullen was dead in the cotton field

and the buzzards would be. at him by now

if nobody hadn’t buried him

and who would there be to bury him

with everybody shot or run away or hiding?

In a couple of days it was going to be Christmas

yes Christmas

and nobody belonging to Cliff James

was going to get a thing

not so much as an orange or a candy stick

for the littlest boy.

What kind of a Christmas was that

when a man didn’t even have a few nickels

to get his children some oranges and candy sticks

what kind of a Christmas and what kind of a country anyway

when you made ten bales of cotton

five thousand pounds of cotton

with your own hands

and you wife’s hands

and all your children’s hands

and then the Laws came to take your mules away

and drive your cows to sell in town

and your calves

and your heifer

and you couldn’t even get commissary credit

for coffee molasses and sow-belly

and nobody in your house had shoes to wear

or any kind of fitting Sunday clothes

and no Christmas for nobody . . .

“Go Down Moses” was the song they sang

and when they had finished singing

it was so quiet in the church

you could hear the branch splashing over rocks

right out behind.

Then the preacher got up and he preached . . .

“And there was a man what fought to save us all

he wrapped an old quilt around him

because it was wintertime and he had two pistol bullets in his back

and he went out of his house

and he started walking across the country to Tuskegee.

He got mighty cold

and his bare feet pained him

and his back like to killed him

and he thought

here is a cabin with smoke coming out the chimley

and they will let me in to the fire

because they are just poor folks like me

and when I have got warm

I will be on my way to Tuskegee

but the woman was afeared

and barred the door again him

and he went and piled leaves over him in the woods

waiting for the night-time

and six buzzards settled in an old gum tree

watching did he still breathe . . .”

The Sheriff removed Cliff James from the hospital to the country jail on December 22. A mob gathered to lynch the prisoner on Christmas day. For protection he was taken to jail in Montgomery. Here Cliff James died on the stone floor of his cell, December 27, 1932.

Tags

John Beecher

“In Egypt Land” is taken from John Beecher’s To Live and Die in Dixie, 1966. Mr. Beecher has been active in popular struggles in the South all his live and published a number of other poetry books. His collected poems will appear in a single volume published by Macmillan in the Spring, 1974. (1974)