This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Ninth Street opens up before dawn, an intimate village within a sprawling city ringed with shopping malls and interstates. Bookended by a bank and a natural foods store, Ninth Street maintains a thriving rhythm through the day as shoppers, workers and merchants go about their businesses.

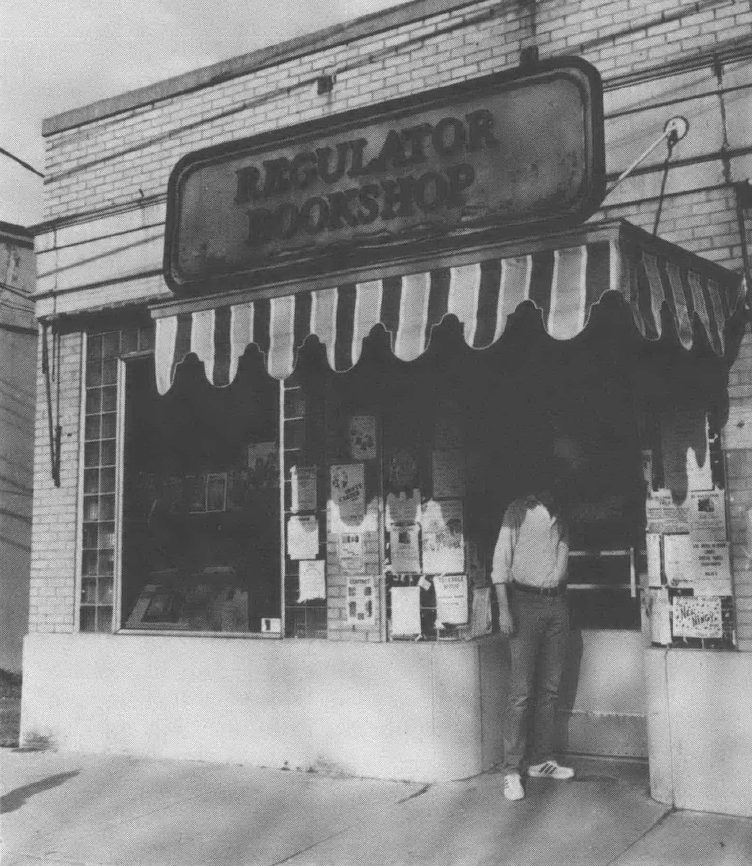

The Regulator Bookshop lives in a converted drycleaning building, sharing the street with a microcosm of American free enterprise: a hardware store, a post office, an auto parts store, several restaurants, a Burlington Industries mill across the street and a very personal drug store complete with a genuine soda fountain. The daily traffic to these and a dozen other small businesses on Ninth Street resembles a melting pot of the North Carolina Piedmont.

The Regulator began as a shared dream of a group of friends who had stayed in Durham after student days at Duke University. Opening a bookshop was one of a number of equally unlikely fantasies, which included starting a newspaper, a restaurant, a coffee house, even a Japanese bathhouse. Then suddenly, in the summer of 1976, a likely storefront came open; one member of the group put down two months rent and a meeting was called. The 12 people who attended that meeting became the board of directors of a nonprofit corporation, Regulator Publications, Inc. The pleasant dream awoke to planning, painting, shelf-building, fund-raising, book-ordering. The Regulator Bookshop opened for business on December 8,1976.

From its outset, the Regulator has been a hybrid of the conventional and the alternative. The store was initially capitalized by a $5,000 bank loan (finally approved at the third bank we approached) and $7,000 in low-interest loans from trusting individuals. None of the money came from the board of directors — none of us had anything to lend. We found that we were viewed as an alternative merely because we opened on a shopping street rather than in a mall and because we were independently owned rather than part of a national chain.

The store was conceived as a general bookshop carrying a quality selection in all areas. But we would have strong sections in areas that were important to us and that weren’t covered well in most other stores — progressive politics, alternative energy, women’s issues, gay and lesbian issues, the environment, children’s books. We added a room of periodicals that reflected our selection of books. Being naturally sympathetic to people of limited means, we devoted one entire room to used books.

When the bookshop opened, odds were about 50-50 that a business with a liberal/radical stereotyped reputation could survive on such a working-class street. Local malls and grocery stores carried 90 percent of what most people wanted to read right there in bright display racks.

Imagine a bull’s-eye target, a series of concentric circles. Maximum sales potential is the center bull’s-eye: Shogun, People magazine. Most chain stores program their stock according to this center targeting approach, ignoring the outer edges. The Regulator Bookshop attempted to carry the missing 10 percent, and is happily surviving after nearly five years. Our approach would be described as “fringe marketing.” So along with Princess Daisy and TV Guide, we sell The Wanderground and Guardian-, next to Mother Jones you’ll find the Saturday Evening Post-, color Xerox post cards beside the Miss Piggy wall calendars.

Access to information is a primary function of our bookstore. There are many great books written that never go beyond a small press network limited by word of mouth. A book not carried in B. Dalton will have a tougher time staying in print than another with a shiny cover on the chainstore counter. We try to even things out, ordering and reordering the more obscure titles that do sell two or three copies a month. It’s more satisfying to sell one copy of a non-bestseller than five copies of books whose primary selling interest was due to the author’s appearance on a TV show.

Suggestions and decisions about what to stock are, of course, major concerns. We survive by having not only what people ask for but by having what they might not know about yet. How many chances we take varies, but a business lives and dies by its cash flow. So certain times of the year the store is playing catch-up with its accounts and not necessarily stocking every new author or magazine. We have to sell x amount of books in x amount of time. Turnover of inventory is more important than just volume of sales. So we juggle the bestsellers with the also-rans and the never-closes.

But the bookshop is beginning to feel like a success. Apart from blind luck, we credit this success to two main factors: service to the community and honest but intelligent business.

Service to the community is more aptly service to subcommunities. Probably half the people that frequent our shop are likely to run into each other only at the Regulator. Some folks are interested only in our used books, some only in used gothic romances, others in our women’s shelves or our books on politics. We serve our many communities by talking to them about their reading, gleaning interesting-sounding titles for our order lists; special-ordering anything for anybody; taking book displays to solar energy fairs, art fairs, folk festivals. We try to make the shop responsive to what people are looking for. On the other hand, we try to lead people to things they might be interested in, given some encouragement. We often point out books to people and give little pep talks about books that we think are especially deserving. Now and then we set up a “manager’s choice” table that ranges from bestsellers to the kinky and obscure.

When we opened the shop, we imagined its future customers having wide-ranging tastes; for those that didn’t, we set out to broaden their horizons by such subtle devices as not labeling our sections and purposely shelving some surprises among the sections we had. A science fiction book about an outer space hospital went on our medical shelves. Right below our mostly “quaint” section of books on North Carolina are our shelves of books about gay men. But by and large our little tricks have been no match for the blinders so many people wear. So to some of our customers we are still seen as a political bookstore that carries a general selection just to stay alive. These folks seem a little embarrassed for us when they hear us con versing with someone else about Edmund Crispin’s 1950s English mysteries (which are almost uniformly wonderful, by the way).

We strive to provide a space where different kinds of people can feel comfortable and unthreatened. There are no signs posted in our store about “no food, no pets.” Bare feet are okay. We encourage a living-room ambiance. We built our shelves out of wood; a built-in sofa and coffee area are at the back of the shop. Customers have learned how to operate the coffee machine, so often we have fresh coffee without it being a chore. It is a good feeling to start work hassled and have people offer to help out in your own store, when they probably came to relax themselves.

Our efforts to be of service have been repaid with the gratifying loyalty of many of our customers. Almost every day someone comes in and buys books that they have seen at another store but they have waited to buy at the Regulator. All of our non-bank loans have come from our customers. In our last loan search, we raised almost $2,000 in $10 and $20 loans from dozens of people. We have been given outright more than $600. Twenty-five or so university professors order their textbooks through us on an exclusive basis. At the beginning of the semester our sales get quite a boost from these textbooks, and hundreds of students are introduced to the shop.

The other half of our “success formula” consists of honest dealing, good organization and a respect for money as a tool and resource. We were forced to learn book keeping, which, although often tedious, yields valuable information about what is happening in the store. After $400,000 of sales, our books contain a fudge factor of under one dollar. Out of more than 3,000 special orders, we have lost track of perhaps a dozen. Good organization frees up time for relaxing and talking with people, provides our customers with better service and allows us to make the best use of our limited capital. We think that good business practices are a lot like good craft work. Most of what’s involved is knowledge, organization and experience, but there’s an important fraction of creativity as well. Most decisions about store policies are made in informal weekly breakfast meetings. We’ve found it easier to discuss nearly all issues away from the store. The distance and openness are important for the store’s growth and for our own sanity. Yet we are a business and we approach seriously the issue of staying alive, the “bottom line.” The freedom to decide what salaries to receive, what holidays to take, which books to promote, when to advertise, is satisfying. That freedom gives opportunity for fresh ideas. Trying something new once sure makes it easier to try something else the next time or to allow someone else to run with his or her ideas. With the benefits of customer interaction, we’ve held used-books-by-the-foot sales, book rentals, had artists display their works, and discussed closing the store during lunch for basketball therapy. Recently, we had a “moral majority” special on Catcher in the Rye and held an autograph party to celebrate the release of records by two local rock’n’roll bands.

The Regulator Bookshop proposes itself as a synthesis. A synthesis of the alternative and the conventional; of books published by the conglomerates and books put out by the smallest of presses; of groups of customers with differing interests and backgrounds; of leading and following these customers; of airing controversial ideas in a non-threatening environment; of doing what we want to do and staying alive as a business. That we have survived and grown for four-and- a-half years is unusual. Achieving any sort of synthesis in this culture is not an easy task. As political attitudes and economic realities become harsher, this task will be all the more difficult. And all the more needed.

Oh yes, about our name. In the 1760s there was an uprising in this area against the colonial government and aristocracy. The upstarts called themselves the Regulators. Their taxes weren’t bringing any benefit. Their farms were being stolen out from under them by crooked courthouse lawyers. They wanted better social services and an end to corrupt, self-serving upper-class rule. They didn’t win, but we identify with their feelings and their spunk.

Tags

Tom Campbell

Previously a recreation therapist, John Valentine has worked at the Regulator for two years. He currently makes buttons for local rock’n’roll bands in his spare time. Prior to helping found the Regulator, Tom Campbell worked as a journalist, a teacher of emotionally disturbed children and a dishwasher. He watches very little television. (1981)

John Valentine

Previously a recreation therapist, John Valentine has worked at the Regulator for two years. He currently makes buttons for local rock’n’roll bands in his spare time. (1981)