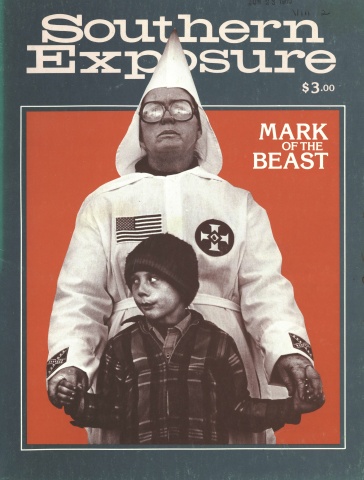

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

It is the winter season slacktime, and there’s not much work on the Mitchell farm but feeding the cows and tending to odd jobs in the shop. Two dozen people from farming families here in Navarro County, Texas, have taken advantage of the slowdown in farm work to join the 1979 farm protest in Washington. Three tractors from the county drive the whole way in the American Agricultural Movement tractorcade. Though Tom Mitchell is not among them, he is following the protest — and the results it achieves — with more than casual interest. He has been active in AAM, too, in his own ways.

Like others in the movement, Tom joined because his farm was being caught in the crunch of costs rising faster than income. His farm lost $8,000 in 1975. The next year it was $20,000. In 1976 and 1977 he had to refinance some of the family land which was almost paid off. This allowed him to catch up on some of the equipment payments the bank had been carrying for him. But it was a painful sacrifice. Most of the land he farms is owned by landlords, and the bank holds notes on most of the farm's equipment. That family land was source of pride. It was also the most tangible fruit of his parents' long years on the farm.

january

Keeping the cattle fed is the major accomplishment of the month. There are four small herds — 79 “momma cows’’ and four bulls in all — on pastures in four different directions from the tiny East Texas community of Barry. Tom checks up on his stock from time to time, but leaves most of the hay-hauling to the two full-time hands who work through the winter. It’s an every day of the week job, but the work is usually done before the morning is over. A junior college student from nearby Corsicana who works for Tom during the summer comes out to the farm every so often to keep in touch and help out with the work. Pay, feed, repairs and fuel for the month cost $5,202. There is no income.

february

The sodden weather continues, and getting hay, straw and cotton seed to the cattle remains the major chore. There is also shop work, getting equipment ready for the planting, which should start in March. Two tractors go to Corsicana for repairs. The operating loan of $72,000 comes in, allowing Tom to make the annual payment of $1,115 on the mortgaged family land and pay off an $8,000 fertilizer bill. In all, the expenses come to $15,21 7. There is no income. The farm is running $20,419 in the hole.

Like a growing number of younger farmers, Tom did not have to be in the fields. He chose to. With a BS in education and a master’s degree in biology, Tom had carved out a successful teaching career — 12 years in all at high school and college level. “I enjoyed teaching and still miss teaching, but I began to want to be my own boss,” he recalls. His father, George Mitchell, was about to retire from the farm started by his grandfather a century before, so in 1974 “with about $5,000 and a pickup truck,” at the age of 35, Tom went back to the farm.

Even when Tom was a boy, a “family farm” was not something one family could handle on its own. But beginning with the years just after World War II, the face of farming has changed almost beyond recognition. The hand labor which dominated the farm in his boyhood days gave way to increasingly sophisticated machines.

“I can almost see my father get up at four in the morning and go into Corsicana to pick up blacks to hoe the cotton,” he recalls. “He would make the east side, picking them up at their houses. They would stop at Lee’s Grocery, and he would loan the hands enough change to buy summer sausage and a pack of crackers for lunch and bring them out to the farm to go to work.”

About 30 hands, hired on a day labor basis at cotton chopping time, hoed the weeds out by hand. This work was done early in the cotton cycle, and a smaller crew was brought out later for some clean-up weeding. All 30 were needed again when it came time to pick the cotton. Tom’s own work included chopping cotton, scooping feed and throwing bales of hay on and off trucks. He remembers driving a tractor through the cornfields at the age of seven or eight while farm hands pulled corn and tossed the ears into the trailer behind him. “One of the hands had to put in the clutch,” he recalls. “I couldn’t reach the brakes; I could only steer it up and down the row.” He drew water by hand from a well to fill two 30-gallon water flasks they took to the fields for the hands to drink from during the cotton-picking season. And he babysat for the small fry who came to the fields with their mothers.

The family farm back then — land worked by his father and his grandfather both — never added up to more than 250 acres, and cotton was about the only cash crop. Now Tom and his father (when a farmer says “retired,” it always has quotation marks around it) work 1,550 acres. 1,150 acres of crop land are divided among cotton, grain sorghum and wheat. The rest of the land is pasture, hay meadows and waterways.

It seems paradoxical to see someone like Tom — drawn back to the farm in a search for independence — linking himself with other farmers in a movement like AAM. But the very existence of AAM is a paradox. Virtually all the farmers in it are as independent-minded as Tom. Some are older, some younger; some are firebrands pushing for direct action, others quiet like Tom. Some see farming as a way of life; others see it merely as one way of several that they can make a living. All have a sense that the family farm, even in its modern-day mechanized incarnation, is in danger.

“For years and years farmers were a most individual kind of person,” Tom says. “But in the last two or three years a large number of farmers have discovered that they can no longer remain independent. If we’re going to continue to exist, we’re going to have to get together. If you consider a world of labor unions demanding their wages, if you consider we’re living in a world where large corporations are paying lobbyists for legislation oriented in their direction, then independent, individualistic farmers must realize they have to get together to accomplish the necessary goals in the agricultural world.”

Henry “Pie” Davis takes the wheel of the tractor and trundles out to the fields. After years of practice he makes the intricate planting maneuvers look simple. The throttle never moves. Pie shifts the gears, touches the hydraulic controls, mashes the right brake pedal to the floorboard and spins the steering wheel. The huge tractor pivots on the motionless inside set of twin rear wheels; the plow quickly lowers again into the moist but crumbly soil; the blades bite in, turning another ribbon of earth. The wheat in this field was stunted by a herbicide used to keep grass out of last year’s sorghum, and Tom has decided to plow under about 100 acres.

This year Mitchell will set up test plots to see whether the Miloguard — a pre-emergent herbicide designed to keep grass out of grain sorghum fields — can be used in lower doses. On some plots he will try a post-emergent herbicide, too. Those experiments will help Mitchell plan for future crops, but for this year there’s nothing to do but plow the stunted wheat under and prepare the fields for cotton. The weather allows them about seven days work in the fields. They are able to “top dress’’ all the wheat — about 230 acres — with ammonium nitrate fertilizer. They have to make three trips across the land they are changing from wheat to cotton to get it ready for planting. march Rains keep Tom and his crew on edge most of the month. Planting should have started by the tenth, but the fields remain too wet all through March. There are enough dry days to get fertilizer spread in the wheat fields. The cattle are wormed, treated for ear ticks and sprayed for lice. The calves are ear-clipped for identification and vaccinated against black leg. And the bull calves are castrated; steers gain weight faster than bulls. The month’s expenses total $4,815. There is still no income, so Tom’s farm is $25,234 in the red.

april

It was touch and go, jockeying with the persistent rains, but Tom Mitchell got all his milo seed in the ground this month.

A week and a half ago Tom was on the tractor himself, spelling his hands while they went for lunch, 311 acres of planted grain sorghum behind them. And the rains returned.

“I planted the last three acres at seven miles an hour with the windshield wipers going,’’ he says. “That was the fastest planting I’ve ever done. Some people may wonder what we need windshield wipers on a tractor for. You can tell them about that.”

Not all the farm’s tractors have wipers. Most don’t even have cabs. But the newest, fanciest, largest tractor is the one which does the planting. It can carry an eight-row cultivator on the front and the planting attachment behind, doing two jobs at once. There were only nine days this month when the fields were dry enough to work. On the busiest of those days, four tractors were running at once, spraying pastures for weeds, fertilizing milo fields with anhydrous ammonia, planting the milo, and rolling the earth over the seeds to hold in the moisture.

Even Tom's ‘'retired" father, George Mitchell, was in the fields, on that final tractor, rolling the fields. Tom was supervising and picking up the loose ends.

There is no way Tom can keep up with all these chores without his trusty pickup, but the pickup gave up this month. The camshaft wore out. The new pickup adds $7,000 to April’s expenses, which total $19,670. The year’s first income flows in, from the sale of 28 calves and a few bales of hay. It adds up to $11,340. The farm ends the month $33,564 in the red.

The longer Tom stays with the farm, the easier he can remember things he needs to know when he is on the run. The reason he can tell you that last year he spent $5.63 per hour of field time, though, is the records he keeps.

These records begin with the small pocket notebook Tom carries with him to record tasks to be done and field notes to be transferred to the thick ledgers waiting at home.

There, he charts the inputs — seed types, type and amount of fertilizer, chemical applications — and the yield. After a period of years, to give time for weather variations to smooth out, he can pull out numbers from these records showing which crops respond better to fertilizer, or which fields are better for which crops.

Or at the beginning of a year, when he expects perhaps 20 pounds of lint per acre and a price of maybe 53 cents a pound for cotton, he can review the costs of planting the crop and harvesting it, and see whether it will pay.

“This is the ultimate to record-keeping,” Tom says, “knowing that break-even point.”

Some things changed for the Mitchell family when Tom went back to the farm. For one, they had to give up their garden. That had been Tom’s project, and now there is no time. Right when the garden would need the most attention, Tom is working “from can ’til can’t” on the farm. The family’s schedule changed, too. Tom’s wife Zoe Ann laughs as she recalls Tom’s wishful thinking when he first went back to the farm: “Tom said, ‘I plan to have a schedule where I can get through about five in the afternoon except in the heavy times.’ That slipped. Now he keeps hours like his dad did.”

Other things have stayed the same. The Mitchells still live in a comfortable ranch-style brick home in Corsicana, county seat of Navarro County. Tom commutes the nine miles to Barry. Zoe Ann still teaches physical education and coaches at Collins Middle School in Corsicana. She leaves the farming to Tom. It doesn’t interest her. It is increasingly common for the women in farm families to work. Like Zoe Ann, over 41 percent of these women were part of the labor force in 1977. This compares with 29 percent in 1960. Two-thirds of the working women, like Zoe Ann, have jobs outside agriculture, and that percentage is growing.

Christi, now 17, is the only other family member who shares Tom’s interest in agriculture, and that is not a direct result of Tom’s farming. A school friend got her interested in showing cattle, and she’s now active in 4-H and FFA. She’s of two minds about what she wants to do in the future. “One of these days I’d like to have a registered herd of Herefords,” she says, “but I’d also like to teach.” In the spring and summer she sometimes shows up at the farm to help out and learn a little more about the operation — but on her own, not drafted, as Tom was when he was a boy. Even the simplest of the tractor-driving jobs is not so easy as it looks. The tractor starts bucking as Christi tries to turn at the end of the row. “Clutch, girlie, clutch!” Tom shouts, though there is no way his voice can carry all the way across the field. Gradually she’s getting the feel for it, but it takes time.

Brian, 13, shares his mother’s interest in sports. He pays little attention to the farm. “Sometimes I go out and ride with Daddy on the combine,” he says early in the year. “And I like to watch — like when they move cows from field to field. I like to get little sticks and poke the cows in the trailers.” Later in the season he shows more interest, and even learns how to pilot the smaller tractors. But Tom is not sure whether Brian is really interested in the farm or whether he is just motivated by the extra pocket money he gets for helping with farm chores.

The uncertain pace of farm work cuts Tom out of family activities more than he might like. “It’s hard to say, ‘Yes, Christi, I’ll take off. I’ll be happy to transport calves and equipment to San Antone for you,’ and be gone the three or four days of the livestock show there,” Tom says. The show in San Antonio, right at spring planting time, is one of the three biggest in the state. “So instead you say, ‘If I’m not busy and you need some help, feel free to holler at me.’”

Tom tries to be as available as possible, though, especially outside of planting and harvest seasons. “Zody (Zoe Ann) and I both talked along the lines there’d have to be some give and take both ways when I went back to the farm,” he says. “I have to realize that she’s working and some of the take-the-kids- to-practice, a certain amount of pick-em-up-and-carry-them-to-school are my responsibility as well.”

may

Most of the cotton is planted. This includes 80 acres which had to be planted a second time. Rains and chill weather conspired to keep the seed from sprouting. The sorghum has grown from tiny seedlings to foot-high plants. Already there are insect problems in many of the sorghum fields, and Tom's father George is spraying insecticide to knock out greenbugs. Fuel allocations are announced, but so far Tom has felt no impact on the farm’s fuel supplies. Expenses for the month are $2,534. There is no income, so the balance for the year now stands at a negative $36,098.

june

The month is nearly half over and 60 acres of cotton land still need to be planted. There is hay to cut and bale. And the wheat is ready for harvest. Tom, George, three full-time hands and eight parttime and seasonal workers get little rest for nearly three weeks. They are busy 14 hours a day, six days a week, and they barely slow down for Sundays. The wheat crop is good, though — better than 41 bushels an acre. Prices are good, too — as high as $3.90 per bushel, with an average of $3.50. Fuel supplies have not been cut, but fuel prices are going up. Total expenses for the month are $14,774. Income is $28,349. For the first time the monthly balance is in the black, but for the year expenses are still $22,523 ahead of income.

As he runs between jobs, Tom stops at Barry’s combination filling station and general store for two Dr Peppers and a pack of cheese crackers. “Days like this we live on these,” he says. “I didn’t even get a cup of coffee before I came out.” Tom sees his role on the farm as that of manager, but it’s no desk job. His office, more often than not. is the front seat of a pickup. And especially during the busy season he does a lot of plain and simple tractor driving. One day in June he reconstructs a list of all the work he did that day. It fills four pages of notebook paper. The jobs include jockeying pickup trucks around so tractor drivers working in four different directions from town can get back to the shop if they have problems, taking care of flats on two tractors, bringing in a load of fertilizer from a nearby town, getting two pickups to a field to jump-start a tractor with a 24-volt electrical system, buying hay seed, checking with the veterinarian who had to do a caesarian section on one of his cows, and item after item of emergency repairs to equipment or transporting hands from one field to another.

At the end of each month, Tom’s budget promises him $600 for his trouble. In good years he will have more from farm profits. In bad years he may go into debt to cover just the $600. But in either case, his hands have much smaller paychecks. Tom pays the going rate in the area. For a full-time hand, that’s about $200 a month. Some informal fringe benefits soften the stark prospect of trying to provide for a family on that wage. These can include use of one of the farm’s pickups, emergency loans, or free rent and utilities in one of the deteriorating houses still standing on the farm. Sometimes a hand is given a share in the profits of part of the operation. The job is nothing someone would do solely for the money, though, and because farm work itself requires an increasing level of mechanical skill, working on a farm is becoming much more like working in a factory.

Many who used to work on farms have gone north to Dallas for jobs. Over the course of the year both of Tom’s full-time black workers leave for city jobs. It’s not the first time they have left, and as before they return to the farm. In Navarro County, though, being a black farmworker is usually a dead-end street. Pie, who is Tom’s main combine operator, is hoping for better.

Pie has worked on the Mitchell farm far longer than any other hand who is still there. He was working for Tom’s father George before Tom came back to the farm, and operates the heavy equipment with a deft touch which shows his years of practice. Tom trusts him with equipment and jobs he won’t let any of the other hands touch. Pie takes care of basic field repairs, too, though he leaves more complicated work to Tom.

Pie’s family comes from neighboring Henderson County. The southeast comer of the county, now half flooded by a huge reservoir, is unusual because of an enclave of black farmers who struggled and saved to buy their own land. Pie’s grandfather was among them. When the lake — Lake Palestine — was built, Pie recalls, his grandfather refused to sell any of his land. “They can flood it, but I’m not going to sell.”

Pie’s own dreams are rooted in this spirit of proud independence. For years he and his family have been living in one of the old farm houses which dot the countryside. Some area farmers (though not Tom) still refer to them as “nigger houses.” Pie’s is bigger than most, but the porches are collapsing, the carcass of an abandoned automobile sits in the weed-choked front yard, and the chill of blue northers whistles through the clapboard walls. Rent and utilities are free.

During the course of the year Pie moves. With Tom’s help on the paperwork, and a parcel of land his brother has given him, Pie has built a new brick home on an FHA loan.

The new home adds to Pie’s needs and hopes. “I told the boss I’d like to have a little more share in things,” he says. “I just borrowed $25,000 for that house, and I don’t want to be paying on it for 30 years.” Pie does have part interest in one cow, and would like to expand on that. “I might get me some cattle if I can find some land to put them on,” he says. Land is not easy to come by, though. And Pie is limited, too, by the fact that he does not particularly like reading and paperwork. They are skills even a small farmer needs these days.

Late in the season Pie and Tom come to an impasse in discussions about Pie’s “share in things.” He leaves the farm for an unskilled job at the county hospital. It is not the first time he has left, but Tom is not sure whether he will be back or not. In a month, though, he returns. He likes the work of farming — more, at least, than the city jobs he has tried so far. Pie is tom between that preference and the desire to make a better life for himself and his family. It remains to be seen how long he will stick with the farm. But in a time when it is difficult for a college-educated farmer with sales of more than $100,000 to stay in business, Pie’s chances of gaining the kind of independence his grandfather did are slim.

Other workers on the Mitchell farm are students — usually white — from the high school or junior college in Corsicana. They work part-time in the school year and full-time in the summer. For them the work is a steppingstone — a chance to learn the ropes and perhaps get a toe hold in farming for themselves. Steve Ragsdale, for example, already owns several head of cattle. Tom puts him in charge of hay cutting and baling this year — both the work on the Mitchell farm and “custom” work done for other farmers. This gives Steve some management experience and a chance to share in the profits from the custom work.

Besides this year-round labor force, Tom’s operation still needs some less-skilled seasonal labor in the summer months for chores like hoeing weeds, mending fences and clearing brush. Some area farmers hire women and children from rural black families for these jobs. Tom, like most, depends on migrants, most of them Mexican citizens. It’s not a matter of choosing them over local black workers. There aren’t that many local people who still hire on — not for that kind of work, and not for the wages that farmers pay.

Tom finds it hard to imagine what the farm labor force of the future will be. He sees the fulltime workers in the area slipping away, and he doesn’t blame them for leaving. He knows they can make more in the cities. “I would like to pay better wages, but if I paid what I’d like to pay, I’d be out of business,” he says. This skirts the question of whether he could afford to pay more — and whether he would be willing to buck community pressure, which decrees low wages.

It is true, though, that labor costs are the second largest item in Tom’s budget. The only thing larger is rent. Tom’s farm is pieced together from parcels, none bigger than 240 acres, owned by nine landlords. On the crop land, his rent is a share of the crops — a third or a quarter — and so it varies from season to season.

july

This turns out to be the best month of the season for a vacation. The wheat was harvested in June, and the sorghum will not be ready until August. “Evidently we’ve had our vacation and just didn’t notice,” Tom laughs. The month has been spent in keep-up and catch-up chores — equipment maintenance, fence repairs, weed cutting and generally keeping tabs on the crops.

For a while Tom had three tractors in the shop in Corsicana at once. One had a radiator problem, another needed work on the hydraulic pump, and the third had to have the fuel injector pump fixed.

He took the generators off a fourth tractor and one of the grain trucks and sent them in for overhaul. The welding equipment at the farm’s shop was enough to take care of a pasture shredder which broke.

Now that the seed is in the ground and the plants are up, the cotton and milo crops are, to a certain extent, at the mercies of the rains and the sun. The good, unusual rains put more moisture in the soil and greatly improved this year’s crop prospects, Tom says. On the other hand, heavy rains in July increase the chances of root rot in cotton plants. When the root rots, the plant dies. Some of the soggier spots in cotton fields around Barry are already beginning to turn brown.

Fuel bills hit hard, adding $2,360 to the month’s total expenses of $7,813. There is no income, so the balance at the end of the month is $30,336 in the red.

august

The sorghum harvest begins. It isn’t spectacular. Because the planting season was so stretched out, the harvest has to be stretched out, too. In some fields Tom decides to combine the grain before it is completely dry just to get it done and out of the way so the fields can be prepared for next year. This means the grain has a high moisture content, and prices are lower. The check for the sorghum he’s sold will not come until September, so the cash flow for the month is all outbound — $4,999. The deficit now stands at $35,335.

“They say a farmer spends 364 days a year producing his crop and one day selling it,” Tom says, “while a buyer spends 365 days of the year buying or looking at the markets.” The big buyers on the agricultural commodity markets may be as far away as Chicago or New York or as close as Fort Worth. They calculate the possible impact of flooding in the Dakotas or droughts in the Soviet Union, then forecast commodity prices a year and more into the future. “The buyer knows a whole lot more about the potential income from our products than we farmers do,” Tom says. “So a great deal of farm marketing becomes taking the product to the buyer and saying, ‘Here, what’ll you give me?’ rather than knowing what our product is really worth.”

It’s a marketing system with so many middlemen that a loaf of bread on the store shelves contains only about three cents worth of wheat. Farmers who want to survive will have to become much more canny in the market, Tom believes. One way — a method which will short-circuit at least a stage or two in the marketing chain — is a new computerized, cooperative marketing system Tom helped bring to the county in 1979. So far it is used only for selling cotton, though it may expand to other crops in the future. It allows a cotton farmer to put his crop on the block before some 47 major world cotton buyers, who handle 90 percent of the cotton produced in the United States.

The system is an indirect result of AAM. “We became united through the agriculture movement and continued with this because we knew we could get something done together,” Tom says. It’s hard to tell this first year what the effects of the new system are, but Tom is optimistic.

AAM was, for the first two years of its existence, a nebulous not-quite organization. There was no formal membership, and people participated at various levels. Meetings were irregular, and depended on what was happening and what needed to be planned for. From his comments Tom seems to be one of the quieter supporters who gave money, attended local meetings and helped with pressure on legislators. Tom and others like him supported the AAM goal of making the public and legislators aware of the plight of the family farmer, but shied away from what Tom calls the “agitative” approach: blocking traffic, for instance.

september

The sorghum is all harvested and most of it is sold this month. This is also the time to start preparing the land for next year’s crops, which means Tom has to decide what will go where. To some extent this follows naturally from his three-crop rotation, but not completely. Expenses run $10,223. Income is $31,420. For the year Tom is only $14,138 behind now.

october

In a “normal” year the cotton would have been harvested this month. This year the harvest has just begun by the end of October. Most of the month is taken up with planting wheat for winter grazing, working cattle and getting the cotton strippers and trailers ready. Expenses are $5,417. Income, from the sale of four old cows, is $1,655. The year’s deficit takes a jump to $17,900.

The cotton harvest begins with the application of a chemical which, in the right amounts, dries the leaves without killing the plant stem so the bolls can continue to ripen. This handy chemical is an acid compound of arsenic. It is dangerous. It can cause rashes, swollen eyes and nausea. Tom handles it himself rather than entrusting it to his hands. If he thought there were a safer substitute, he would use it. But Tom is no organic farmer; he believes that at the right times and in the right amounts, chemicals are necessary to modern agriculture. He also uses chemical insecticides and herbicides, not to mention chemical fertilizers — nearly $20,000 worth of fertilizer for the year. He uses nonchemical controls when he can, though, like the insect-resistant strain of sorghum he tested this year. When herbicides used on last year’s sorghum stunt some of this year’s wheat, he looks for a better way. “I don’t think chemicals will ever take the place of some manual labor,” Tom says. “Excess use of chemicals will deter the plant you’re trying to propagate. I find you need to back off chemicals and spend some time hoeing.”

Although Tom follows some basic soil conservation techniques — he is a leader in the county in introducing wheat into the cotton-sorghum rotation, and he plows most of the stubble from his crops back into the fields — he thinks we have already come close to hydroponic farming, or growing crops in chemical solutions, like laboratory cultures in petri dishes. “From the standpoint of natural productivity, we and our ancestors have pretty much worn out the soil,” he says. “My question — and it would lead to gigantic discussion — is should we spend our finances in an attempt to return organic matter to the soil or spend it on chemical fertilizers? I’ve got a certain amount of money to spend. Where do I put it?” The more crop residues are plowed into the land, the more fertilizer he needs, because some of the nitrogen fertilizer is used by bacteria during the process of decomposition.

“If our grandfathers could see our farming practices, it would simply be unimaginable to them,” Tom says. “If we could look a generation into the future, that would be our first impression — like our grandfathers — to say we’ve advanced as far as it’s possible to advance.

“But in my short farming career I’ve seen changes unimaginable four or five years ago,” he continues, ticking off just a few examples:

· electronic seed counters on planters;

· electronic grain monitors for combines;

· chemical control of weeds;

· twin seeding of grain sorghum to increase production; and

· new markets for farm products, such as selling grain for the manufacture of gasohol.

“There is in the experimental stage right now a machine which moves on tracks through the fields,” he says. “It plows, fertilizes, applies weed control, plants and irrigates electronically, all on one pass.”

Those 60- to 80-row behemoths will be used for very high intensity vegetable farming — beyond the reach of the family farmer. It will be corporate farms which put them into the fields.

“There will always be a place for the family farmer — the individual — but it will definitely decrease,” Tom says. “It will reach the point where the corporations control the agricultural economy, where they control the prices.”

november

The cotton harvest is nearly finished this month. Tom plows 60 acres under because there isn’t enough cotton on the plants to make it worth harvesting. Over all, though, he brings in better than a half bale an acre on 400 acres. It’s no record, but it isn ’t a bad harvest. He also gets the wheat for next year’s harvest into the ground and spends a lot of time in the shop, putting plows and brush cutters into shape. Cattle have to be rotated to new pastures, and the sorghum fields are prepared for the next crop.

“In a ‘normal’ year — depending on how heavy the dew is and when it dries — it may be one o’clock before we can get the strippers into the fields, ” Tom says. “This year it’s short lunches and the weekends kind of run together.”

On a good day there will be three strippers in the fields. Tom drives one, and Steve Ragsdale and Lawrence Moore are on the others. Tom’s “retired” father, George Mitchell, shuttles back and forth from the fields to the gin in Barry, hauling the full cotton trailers in and making sure there are empties for each stripper.

With repairing and re-repairing, the Mitchell farm can count as many as 14 cotton trailers. Sometimes that’s enough; sometimes it’s not.

“Sometimes you reach the point where there are no trailers,” Tom says. “They’re all on the gin yard. But there’s a lot of sharing and ‘Loan me trailers you’re not using’ — a lot of cooperation between people. It makes it kind of nice.”

The money has not come in from the cotton, so the month’s books only show the $4,290 in expenses. For the year Tom is $22,190 in the red.

december

“We have made the cycle,” Tom says. “We are at the point where just feeding the cattle is the daily routine again. And it’s greener on the other side of the fence. So we’ve done some fence repair — sometimes before and sometimes after they got out.”

Some of the cattle that got out turned up as far as five miles away by the time they were tracked down.

Other cattle had to be moved to winter pastures, herded down the dirt road from horseback; 10 calves went to market; and Tom hired outside help to brand and work some of the calves.

It is time for the whole herd — 72 cows and four bulls — to be wormed and de-loused, but that work will have to wait until the schedule allows. And about 20 baby calves need to be castrated and ear-marked.

The last of the cotton comes out of the fields, the cotton stalks are cut in next year’s milo fields and the land is plowed and bedded into miniature hills and valleys stretching across the landscape. It happens later than it would in a “normal” year, but the books start showing some pluses. Expenses this month are $30,066, but there is also $71,755 on the income side of the ledger. For the year Tom comes out $19,499 ahead.

If every year turned out like 1979 did for Tom, farming would be a more attractive occupation. Tradition says, though, that a farmer will have one bumper year, then scrape through for the next nine. To evade that risk, American farming has been moving in two directions. On one end are the massive corporate-owned agribusinesses like those in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley and in California. Fifty-three percent of the farm market in Texas is now dominated by six percent of the farms.

On the other end are people who hold down a city job and farm as an evening and weekend sideline. Tom and most other members of the American Agriculture Movement teeter somewhere in between. To make a living from their farms, they need gross sales of $100,000 or more. Tom’s gross sales in 1979 were almost $140,000.

Though Tom believes that the AAM has made some legislative progress, it clearly has not succeeded in its main goal — having target prices set at 100 percent of parity. (At full parity, sale of a bushel of wheat would give the farmer the same purchasing power it did in 1914.) AAM has settled in for the long haul. It has incorporated and elected formal officers, and it will concentrate on lobbying national and state legislatures.

In the meantime Tom and other family farmers have to find ways to keep going. The main elements for Tom are: (1) more sophisticated management of the farm, which begins with keeping careful books; (2) better understanding of the complex commodities market and an increase in cooperative buying and selling by local groups of farmers; (3) “custom” combining and hay work for extra income; and (4) Zoe Ann’s salary. These, plus the simple fact that he wants very much to continue farming, will probably keep Tom going.

“I don’t think you can take the esthetic values out of farming,” Tom says. “If you’re paid a wage, that’s fine and good. It gives you a certain amount of assurance. But in my case there’s more to living than knowing that if you do a job each day, at the end of the month you’ll get paid regularly no matter how you do the job.

“I’ll never get rich. Still, I’ve got a desire to reach a point where what I own is paid off, where I’m not bound by anybody, where I’m independent. But that’s off in the future. That gives me a goal to shoot for. The old farmer has got to be the eternal optimist.”

Tom doesn’t feel sorry for himself and doesn’t ask anyone else to. The fact is, for all the uncertainties each year brings, Tom and his family live a pretty comfortable life. But he and other AAM members have raised fundamental questions about the changing structure of American agriculture. It already takes more than four times as much land to have a survival-level farm as it did just a generation ago. The next generation’s chances of farming their parents’ land are diminishing year by year. If the balance is not tipped back in favor of family farmers, a way of life — one which has been a bedrock of American culture — may in fact vanish. More than that, as one county agricultural agent put it, “When Ford and General Motors own that land, they will say potatoes are 80 cents a pound, and if you want potatoes you will have to pay 80 cents a pound.”

Tags

John Spragens

John Spragens got to know the Mitchell family while working as Farm Editor of the Corsicana Daily Sun He is currently co-director and Indochina specialist of the Southeast Asia Resource Center in Berkeley, California. (1980)