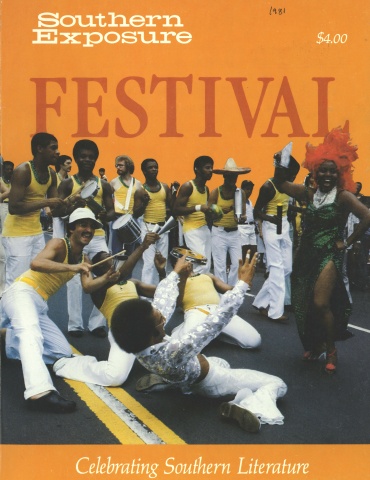

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Combustion Spontanée

Pourquoi ecrire

Personne va livre.

Tu perds ton temps

A cracher dans le vent.

La poesie, c’est grand,

Pas pour les enfants,

Ni les illettres,

Ni les accultures.

Ils ont rien a dire

Et, qa qui est pire,

Meme s’ils en avaient,

II faudrait le faire en anglais.

Mais qa change

Dans la grange.

II y a du nouveau foin

Entassé dans le coin

Et il va se faire voir, lui.

Il a attrapé de la pluie.

When Jean Arceneaux penned this poem in 1979, he gave voice to the feelings of thousands of his fellow Acadians, or Cajuns, those hard-working, hard-drinking, hard-playing descendants of the Nova Scotia exiles deported by the English in 1755. Hardheaded and easy-going, suspicious and hospitable, religious and anti-clerical, conservative and anarchistic, the Cajuns have regularly disobeyed their rulers, insolently challenged their “betters,” and consistently baffled outside observers. Today they are living a cultural revolution while thumbing their noses at the traditional purveyors of culture.

Louisianans once believed the Cajuns’ language was a patois, “not real French;” their music was “nothing but chanky-chank;” their oral literature was doomed to well-deserved oblivion. For many Louisianans, to be French, to participate in French culture, was to be marked as ignorant and inferior. But for the Cajuns, French language and culture have always been central to their identity. For a while they outwardly accepted as inevitable the Americanization of their culture, language and values, but, as “Combustion spontanée” points out, French remained alive and traditions remained strong, albeit under the surface.

Certainly Cajuns have enjoyed the new affluence that came to their state with the development of the oil industry; they bought big cars and televisions as readily as other Americans. But “Americanization” left them with a sense of loss. They suspected they could not live by sliced bread alone; boudin and gratons, those traditional Cajun delicacies, would greatly improve the fare.

By the 1940s, Cajun music — a vital element of the culture — was all but gone after nearly a decade of influence from Western swing, country and bluegrass. The diatonic accordion, the symbol of this forsaken music, had lost its dominance during World War II when German factories could no longer supply instruments. And the rural French Louisianans seemed headed toward the melting pot like their urban counterparts, the French Creoles. Compulsory English education, the prohibition of the use of French in the schools, and the English-language mass media seemed certain to doom the culture to extinction.

Then in 1948 a young folk musician named Iry Lejeune recorded a song called “La Valse du Pont d’Amour” and provided the catalyst for a revival of traditional Cajun music. His record was an unexpected success. Following Lejeune’s lead, other musicians dusted off their abandoned instruments and tunes and once again performed the old Cajun music.

These folk musicians, who could neither read nor write music or French, composed new songs in the old style — and unwittingly started a Cajun literary renaissance. The songs formed a natural bridge from an oral to a written literature, their lyrics constituting a small but important body of work suited to a society not yet literate in its own language. The themes are traditional: the pangs of unrequited love, the burden of poverty, the wages of sin. But the composers, like their spiritual ancestor Francis Villon, could say, “Je ris en pleurs.” I laugh in tears. And their cries of pain are veiled in jocularity.

Although nearly blind, Iry Lejeune traveled and played throughout southwest Louisiana, his accordion in a gunny sack, writing most of his songs himself with the help of his friend and recorder, Eddie Shuler. Iry was killed in an automobile accident in 1954 at age 27. “La Valse de Quatre-Vingt-Dix-NeufAns” is typical of his music:

Oh, moi, je m ’en vas

Condamné pour quatre-vingt-dix-neufans.

C’est par rapport a les paroles toi, t’as dit

Qui m ’ont fait souffrir aussi longtemps comme qa.

Oh, c ’est tous les soirs,

Moi, je me couche avec des larmes dedans mes yeux.

C’est pas de toi, bebe, je m ’ennuie autant.

C’est de ces chers enfants je connais qui miserent.

Oh, c ’est plus la peine,

Tes menteries vont te rester sur ta conscience.

La vérité va peut-etre te faire du mal,

Mais quelqu ’un va toujours te recompenser.

Other musicians picked up on Iry Lejeune’s lead, and soon Cajun music was stubbornly making a comeback. The revival of Cajun music heralded a general change of attitude throughout the culture. One group in particular, the Balfa Brothers Band, became a symbol of Cajun music everywhere, performing in the United States, Canada and Europe. With Dewey Balfa — a man dedicated to the preservation and development of traditional Louisiana music — at the center, the band came to represent for many the cultural pride of the Louisiana French movement.

Thus the scene was set for the state legislature’s 1968 act declaring Louisiana a bilingual state, acknowledging a state of affairs that had existed all along and restoring official status to the language of the colony’s founders. At the same time the lawmakers created the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana, which is charged with preserving and developing the state’s French heritage. CODOFIL’s efforts, along with other contemporary forces, have helped reverse the process of acculturation so that today many young Louisianans, steeped in the oral traditions, are writing poetry, plays, songs and short prose in French. This renaissance, unlike the French literary movements of the nineteenth century New Orleans French Creoles, has been relatively impervious to outside influences, emanating instead from the Cajun culture itself.

The earliest works in an emerging culture are songs and tales transmitted orally. Then appear drama — usually based on myth and folk tradition — and finally poetry derived from the oral antecedents. Just as the medieval mystery and miracle plays and farces, performed in the churches or on cathedral porches, were among the earliest examples of French literature, so the first Cajun literary work was a play, Jean I’Ours et la fille du roi. Written in 1977 by Richard Guidry and Barry Jean Ancelet with the assistance of the amateur theatrical troupe Nous Autres, Jean l’Ours was based on a traditional story told by Elby Deshotels of Mamou. This tale is woven around a folk hero, the poor but clever and impudent boy who wins the king’s beautiful daughter and a large share of the kingdom with the help of his supernaturally gifted friends. The presence of a king in an otherwise typically Cajun environment surprised neither the storyteller nor the south Louisiana audiences, who took him well in their stride. The production and performance of this first Cajun play tapped the rich vein of oral literature and offered an alternative to mass media entertainment and values.

Other plays followed. Martin Weber et les Maraisbouleurs, in 1978, and also by Guidry and Ancelet, was based on a local legendary character. In 1979 Mille Miseres, by Emile DesMarais, squarely faced the problem of ethnic identity and survival, condemning America’s encroachment upon Cajun tradition. In the same vein, and markedly influenced by New Brunswick Acadian writer Antonine Maillet and her brilliant monologues collected in La Sagouine, Guidry has written a series of Cajun monologues, which are performed in theaters and will soon be published by the Center for Louisiana Studies in Lafayette.

Supported by grants from the Acadiana Arts Council, the first Cajun plays toured the southern part of the state in 1978 with performances in church halls, community centers and high school auditoriums in small communities with no previous experience of live theater. They played to enthusiastic crowds and helped awaken latent literary talents.

Hesitantly at first, young men and women began jotting down their thoughts and feelings. And from these stirrings came Cris sur le bayou, the first collection of Louisiana French poetry published in the twentieth century and certainly the first anthology of Cajun poetry ever assembled. The volume was born of the Paroles et musique performance during a 1978 meeting of the French-speaking peoples of North America, held in Quebec. Asked to insert a “little Cajun story, something typical, you know,” into the program alongside the symphonies and poetry of French Canada, Ancelet and Zachary Richard searched for a more literary piece and discovered a small body of contemporary Louisiana French poetry. A later search turned up still more young activists who felt the need to write. These writers gathered for a regional version of Paroles et musique at the University of Southwestern Louisiana in Lafayette in 1979, and decided to produce the collection. Cris sur le bayou came directly from the heart of the Cajun experience and addressed itself to the problem that preoccupies the French-speakers of Louisiana: how to preserve one’s ethnic and linguistic identity in the face of an encroaching, homogenizing mass culture.

These concerns typically inform the poetry of Jean Arceneaux, a young Cajun who lives on the prairie west of Lafayette. Born in Acadia Parish, he studied in Lafayette and in France. He began writing seriously in 1978, almost by accident, and the bilingual monthly Louisiane Francaise soon published “Reaction,” his first poem. In “Schizophrenic linguistique” Arceneaux expresses the anger of Cajuns who were forbidden to use their native tongue in the classroom or on the schoolgrounds and spent countless recess periods writing “punish work” for breaking this commandment. Gradually they came to believe that French really was a badge of social inferiority and that upward mobility required the acceptance of the gospel according to Colonel Sanders. Then one day they discovered that they needed French to live and feel:

I will not speak French on the school grounds.

I will not speak French on the school grounds.

I will not speak French . . .

I will not speak French . . .

I will not speak French . ..

He! Ils sont pas betes, ces salauds.

Apres millefois, ga commence a penetrer

Dans n ’importante quel esprit.

Ca fait mal; gafait honte;

Puis la, ca fait plus mal.

Ca devient automatique.

Et on speak pas French on the school

grounds

Et ni anywhere else non plus.

Jamais avec des etrangers.

On sait jamais qui a l’autorite

De faire ecrire ces sacrees lignes

A n ’importe quel age.

Surtout pas avec les enfants.

Faut jamais que eux, ils passent leur temps

de recess

A ecrire ces sacrees lignes.

Faut pas qu ’ils aient besoin d’ecrire ca

Parce qu ’il faut pas qu ’ils parlent frangais

du tout.

Ca laisse voir qu ’on est rien que des

Cadiens.

Don’t mind us, we’re just poor coonasses.

Basse classe, faut cacher ca.

Faut depasser ca.

Faut parler anglais.

Faut regarder la television en anglais.

Faut ecouter la radio en anglais.

Commes de bons americains.

Why not just go ahead and learn English.

Don’t fight it. It’s much easier anyway.

No bilingual bills, no bilingual publicity.

No danger of internal frontiers.

Enseignez l’anglais aux enfants,

Rendez-les tout le long,

Tout le long jusqu ’aux discos,

Jusqu ’au Million Dollar Man.

On a pas reellement besoin de parler

frangais quand meme.

C’est les Etats-Unis ici,

Land of the free.

On restera toujours rien que des poor

coonasses.

Coonass. Non, non. Ca gene pas.

On aime qa. C’est cute.

Ca nous fait pas faches.

Ca nous fait rire.

Mais quand on doit rire, c’est en quelle

langue qu ’on rit?

Et pour pleurer, c’est en quelle langue

qu’on pleure?

Et pour crier?

Et chanter?

Et aimer?

Et vivre?

Ralph Zachary Richard, born and raised in Scott, Louisiana, and educated in Lafayette and New Orleans, is another young Cajun with strong roots in the prairies. Immensely popular in Quebec and France as a singer and musician, he prefers to be thought of as a composer and writer of the Louisiana French movement. Like his fellows, he feels fiercely that he needs his linguistic heritage to protect his identity, and he brandishes his imperfect spelling of his language as one of the effects of Americanization and the lack of French language instruction in the schools of his youth. An example is “Poeme Pour La Defense de La Culture”:

Devenu etranger a ma propre langue,

Parler franqais, parler anglais,

cameleon de culture,

c’est quoi, quoi c’est qa

la culture.

Crier Acadien,

Brailler ’Cajin,

Danser, Vivre,

Rire, Porter chagrin,

Porter misere,

Voyager d ’amour.

Dans toute les langues

Du monde, tout l’monde

Criant d’une seule voix

J’su que j’su.

Fin de la tyrannie.

Delivrance a la paix.

Deborah J. Clifton, whose roots are at once in Ohio and in Cameron Parish, spoke Creole as a child. Black, French-speaking and a woman, she attacks white, Anglo-American and male institutions with equal vehemence. “Situer Situation,” for example, is an impassioned affirmation of black agony and a bitter indictment of white refusal to face the reality of that suffering:

Mo, chus lafille d’agonie

Toute ma vie te passe en agonie

Et probablement je va mourir en agonie.

La misere, c’est qa mo l’heritage.

J’ai ete ene a Vagonie, sorti d’eine race en

agonie

D’ein peuple qui jamais conne arien

d’autre

Y’en a qui dit que je I’exagere, que les

problemes de qui je parle c’est pas

vraiment la.

Pour beaucoup I’annee j’ecoute les moun

qui’m disait tout ca.

Mais mon agonie c ’est trop dur

Et je connais bien que la vie est bien

comme qa semblait.

Si tu li qa-icit, tu peux l’aimer ou

l’hair mais dis plus que notre souffrance

est pas la,

pas vraiment la.

Karla Guillory is another Louisiana woman writing in French. Born in Eunice, Guillory’s interest in writing was formed as an exchange student in Quebec. A friend at the University of Southwestern Louisiana encouraged her, and she began to expose her sensuality in verse. She often refers to her poetry as her “French thoughts” because, she explains, she expresses in French what she would never think in English. For example:

Tu es la devant moi avec ton sourire

Mes sentiments s’expriment dans mes

soupirs

Tu me veux, je comprends

Tu me paries, je reponds

Tu me guides, je te suis

Tu me touches, jefremis

Tu m ’inclines, point je ne m ’oppose

Je t’aime, je suppose.

Si te desirer etait gouttes de pluie,

Ah, I’orage dans ma vie!

Carol Doucet is a mild-mannered, soft-spoken high school French teacher who reveals in his poetry an unexpected depth of passion and dissidence. Keenly aware of the importance of his Louisiana French roots, he has pioneered methods of teaching Cajun French in the classroom. His poems describe the Louisiana landscape and its seasons and revolve around traditional customs such as funeral wakes. They reflect typically Cajun attitudes, such as amused tolerance of drunkenness and admiration for toughness, hard work and wit. A case in point is his “Adieu, vieux gaillard”:

Une cinquantaine de personnes sont rassemblees

Au salon mortuaire a Bastringueville.

Sept hommes sont sur la galerie en avant,

Ca fume et ca cause.

De temps en temps on les entend rire.

Les femmes veillent le corps

Au dedans, les hommes sont assis dans le vestibule.

Il etait blagueur, ouais!

Un jour, quand on etait tous la-bas chez Claude Poulain

Il nous a raconte comment lui et Georges Perovert

Ont coupe le poil de la queue du cheval a le neveu

a Theodore Boiscreux...

Il y ena qui sont assis assez tranquilles,

D ’autres craquent des farces.

Bien vite on dira le chapelet.

Ca, c’est un homme qui travaillait dur.

Je l’ai vu un jour lever le bout d’un

De ces grands madriers lui seul.

Deux bougres avaient essaye de le lever.

Il leur a dit de se reculer de la, et il

A pris le bout lui seul et il a marche avec,

Et il I’a grouille la du il faillait. . .

Le temps passe.

Oui, c’etait un bon bougre, ca.

Le temps passe. Et le temps passera.

Michael Doucet is one of the most influential forces in the revival of traditional Cajun music. Especially interested in the roots of the music, he has apprenticed himself to some of the earlier bearers of tradition and recently began teaching a course on Louisiana French folk music at the University of Southwestern Louisiana. He has recorded albums and written songs like this one, in Creole, “Z’haricots gris gris”:

Tout partout au ras du bayou,

Mousse-la balance au gros chene vert.

Cocodris dormi en cypiere,

Fi-folets danse en cimetiere.

Vent plein de cris de loups-garous

Mulattes apes taper rythme-la fou.

Moune-la connait yo li z ’haricots,

Mulattes apes grouiller sont z ’os.

Z ’haricots chauds apes veni plus chauds,

Moune de couleur crient, Grande eau!

Pluie bien frais qu ’apes bouilli,

Pas capable froidi, son j’apes bouilli.

Beaux et belles apes fait ses projets,

Et grand mouma a dit, Gris gris!

Loin, loin en cypriere noire,

Tout quelqu ’un Creole crie, Z’haricots!

Antoine Bourque, another prairie Cajun, was born in Opelousas, brought up at Coulee Croche, and educated in Lafayette. He is a widely published historian who had long repressed his creative inclinations for the sake of scholarship. Well-versed in the history of his people, he conceals the quiet vehemence of his frontier background under an imperturbable exterior. “Premier livre” is one of a series of his poems in which he takes on the Anglo-American establishment directly, showing the complete cycle of cultural pride lost and regained.

Premier livre, la bonne soeur m ’a dit

“You must not speak French on the school grounds,

And those of you who do will spend their recess with me.”

Quatrieme livre, la bonne soeur, tres chretienne, m ’a dit,

“Cajuns are stupid, can’t even pronounce

This, that, these and those.”

Huitieme livre, la bonne soeur, avec un nom tres sacre,

m ’a dit,

En riant, “Stand up and pronounce the name of that

bayou in French again.

It’s so quaint.”

Dixieme livre, mon professeur de franqais au high school

m ’a dit,

“Cette phrase, c’est ce que Ton dit ici,

Mais ce n ’est pas du bon francais.”

Douzieme livre, mon pere, regardent le television,

m ’a dit,

En riant, “Look at all those old coonasses on the Marine

show.

They dance before they can walk.”

Deuxieme annee de college, mon professeur de

francais m ’a dit,

“Tu sais, c’est ce que Ton dit ici,

Mais ce n ’est pas exactement correct.”

Troisieme annee de college, mon roommate de

Shreveport m ’a dit,

“I need some information on the Cajuns for my term

paper. You know.

How they play cards . . . and drink beer. . . and dance

all the time.

Quatrieme annee de college, le grand pere de ma femme

m ’a dit,

“Si tu veux causer avec moi,

Il faudra que tu paries en francais, ’’

Et quand j’ai parle avec mes vielles tantes,

Mes cousins et mon beau pere,

C’etait la meme chose.

C’etait moi, pas eux, en exil culturel.

Culturellement mort.

C’est la que j’ai commence a ecouter pour bien parler

le bon frangais.

Et quand mon vieux voisin m ’a demande au deuxieme

festival de musique acadienne,

“Quoi c’est tu fais icitte? Tu te crois Cajun asteur?”

J’ai repondu sec, “Ouais, enfin.”

Amazingly and gratifyingly, this rebirth of French literature in Louisiana began spontaneously — no official agency, no academy fostered it. Paroles et musique 1979 revealed that many had felt the need to write at the same time and had begun to do so unaware of each other. Some of the young writers represented in Cris sur le bayou had known each other before the collection was compiled, but others were discovered by chance — someone would mention, for example, that his sister had a friend who knew a woman who might have written a few things.

Since then, the University of Southwestern Louisiana — especially through its Department of Foreign Languages and the Center for Louisiana Studies — has been a rallying point for the movement. New poems and short stories keep turning up, and in fact enough have come in to fill a second volume. Paroles et musique 1981 — now an annual event sponsored by the university — will bring together some familiar faces arid introduce new ones. In 1980 the university sponsored Le Prix Theriot, the first Louisiana French poetry competition, and drew some 40 entries from 18 poets. The second such competition will undoubtedly flush new coveys of poets, young and old.

And there is another activity. Working with actresses Amanda Lafleur and Earline Broussard, Carol Doucet and Richard Guidry have organized a touring company, Le Theatre Cadien. The present authors have developed a course on the French literature of Louisiana from 1682 to 1982. French literature is alive and well dans le sud de la Louisiane and it’s apparent that the first cris sur le bayou were not voices crying in the wilderness but choirs heralding a feu de savane, a brush fire, a spontaneous combustion spreading across the Louisiana prairies and into the bayous.

SPONTANEOUS COMBUSTION

Why write,

No one will read it.

You’re wasting your time,

Spitting in the wind.

Poetry is something grand,

Not for children,

Nor for illiterates,

Nor for acculturates.

They have nothing to say

And, what’s worse

They’d have to

Say it in English.

But things are changing

In the old barn.

There’s a new pile of new hay

In the corner.

And this time, it will be noticed.

It was dampened by the rain.

— Jean Arceneaux

LINGUISTIC SCHIZOPHRENIA

I will not speak French on the schoolgrounds. . .. After a thousand repetitions, the message gets through and the reaction is automatic. One no longer speaks French on the schoolgrounds or anywhere else, especially not with the children so that they will not spend their recess time writing that damned punish work. They must not speak French; it would show they are nothing but Cajuns. We must go beyond that, speak English, watch English television listen to English radio like good Americans. Go ahead, teach the kids English, bring them all the way to the Million Dollar Man. We do not need to speak here. This is the United States, the land of the free. We will never be anything but poor Coonasses. Coonass. No, that name does not embarrass us. It is just a nickname. It means nothing; it’s all in fun. It does not embarrass us. We like it; it’s cute. It does not make us mad. It makes us laugh. But in what language do we laugh? And in what language do we weep? Do we shout? Do we love? Do we live?

— Jean Arceneaux

THE NINETY-NINE YEAR WALTZ

I’m going away,

condemned for 99 years,

because of your words

that hurt for so long.

In tears every night,

I go to my bed.

It’s not you that I miss.

I miss my children who suffer so much.

It’s no use.

Your lies will always remain.

The truth will pain you

only until you find someone to help you forget.

- Iry Lejeune

SITUATING SITUATION

I am the daughter of anguish.

I have lived my entire life in anguish

And I will probably die in anguish.

Misery is my heritage.

I was born in anguish, of a race in anguish,

Of a people who have never known anything else.

There are those who claim that I exaggerate, that the problems

of which I speak are not really there.

Most of the year, I listen to people who tell me this.

But my anguish is too painful,

And I know very well that life is exactly what it appears to be.

If you read this, you can like it or hate it, but no longer say

that our suffering

does not exist,

does not really exist.

— Deborah J. Clifton

POEM IN DEFENSE OF THE CULTURE

Estranged from my own tongue,

speaking French, speaking English,

cultural chameleon.

Culture?

What is it?

To cry Acadian,

to scream Acadian,

to dance, live

and laugh, to carry sorrow

and to carry woe,

to travel in love.

In all languages,

everyone who cries out

with a single voice:

I am what I am.

End of tyranny.

Deliverance into peace.

- Ralph Zachary Richard

There you are with your smile and

My feelings show themselves in sighs.

You want me, that I know.

You speak to me, I respond.

You guide me, I follow.

You touch me, I tremble.

You bend me, I consent.

I love you, I suppose.

If desire were raindrops,

What a storm in my life!

- Karla Guillory

FAREWELL, OLD FELLOW

Some fifty people have gathered

In the Bastringueville funeral home.

Seven men on the front porch

Smoke and talk,

laugh from time to time.

The women wake the corpse inside.

The men sit in the hall.

“He liked to joke, I’m telling you!

One day, when we were over at Claude Poulain’s place,

He told us how he and George Perovert

Cut the hair off the tail of Theodore Boiscreux’s nephew’s horse...”

Others sit quietly,

Some crack jokes.

Soon they will recite the rosary.

“He was a man who worked hard.

I saw him lift the end of a huge beam,

All by himself.

Two fellows had tried to raise it.

He told them to step back, and he

Lifted one end, all by himself, and walked away with it.

He moved it to where it was needed.”

Time passes.

“Yes, he was a good fellow, all right.”

Time passes. And time will pass.

— Carol Doucet

PREMIER LIVRE

First grade, the good sister told me,

“You must not speak French on the schoolgrounds,

And those of you who do will spend your recesses with me.”

Fourth grade, the good sister, very pious, told me,

“Cajuns are stupid, can’t even pronounce This, that, these and those.”

Eighth grade, the good sister, with a very holy name, told me,

Laughing, “Stand up and pronounce the name of that bayou in

French again.

It’s so quaint.”

Tenth grade, my high school French teacher told me,

“That is what is said here,

But it is not proper French.’’

Twelfth grade, my father, watching television, told me,

Laughing, “Look at those old coonasses on the Marine show.

They dance before they can walk.’’

Second year of college, my French professor told me,

“You know, that is what is said here,

but it is not exactly correct.”

Third year of college, my roommate from Shreveport told me,

“I need some information on the Cajuns for my term paper. You

know.

How they play cards .. . and drink beer... and dance all the time. ”

Fourth year of college, my wife’s grandfather told me,

“If you want to talk to me,

You're going to have to speak French.”

And when I said a few words in proper French,

He turned to my wife and asked,

“What did he say?’’

And when I spoke with my aunts,

My cousins and my father-in-law,

It was the same.

It was I, not they, who was in cultural exile.

Culturally dead.

That’s when I started listening to learn our proper French.

And when my old neighbor asked me at the second Cajun music

festival,

“What are you doing here? You think yourself Cajun now?"

I answered dryly, “Yes, finally.”

- Antoine Bourque

Z’HARICOTS GRIS GRIS

Everywhere near the bayou,

Moss swings from live oaks.

Alligators sleep in the cypress swamp

The will-o’-the-wisps dance in the graveyard.

The wind is filled with werewolves’ cries,

The mulattoes tap a wild rhythm.

Those people know all about the z ’haricots,

The mulattoes are shaking their bones.

The hot z ’haricots get even hotter.

The colored people cry out, “High water!"

The cool rain which is boiling

Cannot cool, can only boil more.

The girls and the guys are making their plans,

The head man cries out, “Gris, gris!"

Far, so far away, in the black cypress swamp,

All the Creoles cry out, “Z’haricots!"

— Michael Doucet

Tags

Mathé Allain

Mathé Allain, a native of Morocco, is assistant professor of French at the University of Southwestern Louisiana. Barry Jean Ancelet, a native Louisiana Cajun, is director of folklore and folklife at the Center for Louisiana Studies at the same university. Their Anthologie de la Litterature Frangais de Louisiane, a text covering Louisiana French literature from 1682 to the present, is available from Media Louisiane, P.O. Box 3936, Lafayette, LA 70502.

Barry Jean Ancelet

Barry Jean Ancelet is a folklorist at the University of Southwestern Louisiana in Lafayette. (1991)