This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 2, "Special Report from Appalachia." Find more from that issue here.

Central Florida is a stretch of slightly rolling hills, cypress swamps, vast citrus groves, and relatively clean air and water that most Floridians thought of until recently as the most livable area in the state. It has neither the damp, cool winters of the impoverished panhandle, nor the blazing year-round mugginess of the gaudy Gold Coast. The small towns had maintained their oak-lined streets and rural conservatism with equal passion in a largely successful effort to hold on to the ersatz cultural memories of the Old South. All in all, the old were right, the “highland-ridge” area was as comfortable a place to live as existed in the state or region.

Now, however, things are vastly different. Condominiums sprout overnight from cow pastures as suburbs apparently designed from Mussolini’s blueprints for resettlement camps are gouged out of orange groves. The pastoral farm and cow towns such as Arcadia and Groveland find themselves described as “near-by urban centers” in the brochures of the “planned communities” Poinciana Springs and Fantasyland Acres. Inevitably, the question arises: Why? Why is central Florida being turned into Jersey City in tropical drag? Although industry is starting to move in now, such development was noticeably lacking when the boom started, back in 1970. Indeed, the local economy was suffering rather badly then. Phosphate, the area’s principal mineral product, was giving out; the space program was being cut back; and agri-business was gobbling up the acreage of small and medium farmers at a rapid pace. So the question remains--what “saved” Florida’s central highlands for the greater glory of Development? The answer lies in a curious, perverted dialectic that encompasses everything from beach erosion to the weekend luxury camper.

Perhaps we should start unravelling the tangled skein of events in the late 1960s, at Miami Beach, home of Florida tourism. Here, for the first time since the Depression, the flow of northern money was beginning to falter. Mindless over-development had led to a serious lack of usable beachfront space, a problem made even more serious by the rapid erosion of the precious white sand, due to the practice of extending high-rise hotels right to the high-tide mark. On top of all this, prices had risen to a point that made even habitually over-charged New Yorkers gulp in disbelief. Besides, there were just “so many goddamn Cubans! I mean, if we wanted to hear Spanish all the time, we could of gone to Spanish Harlem and saved the $500, right?”

Another important factor in the decline of the Gold Coast was the rebirth of an interest in camping-getting back to the land, as it were, as long as the land was equipped with electric hook-ups and running water. The advent of the huge recreational vehicle and latch-on camper top made these naturalistic yearnings practical, as long as the suburban pioneer possessed sufficient credit (at least $8,000 for a Rec Vee, as they are now known). Of course, the very thought of piloting one of these civilian personnel carriers down Miami’s Biscayne Blvd. was absurd. Obviously, what was needed was someplace else to go in Florida, someplace sort of wild, but with, well, something for the kids to do, and a place to go at night. Your standard wilderness is all right for a few hours but after a while, any self-respecting suburbanite wants entertainment.

And at this very time-this strange interlude in corporate development-the untapped wonders of central Florida caught the ever-alert eyes of the Gnomes of Burbank, the financial wizards of Walt Disney Productions.

Disneymania

Just who actually conceived of Disney World, the mammoth entertainment complex destined to be ten times the size of Disneyland, will probably never really be known. Disney mythology officially maintains that all wisdom flowed from the head of Big Walt. Insiders speculate that Walt’s brother Roy was the main man of the Florida project, though of course, it’s always possible that ultimate credit may rest with some senior accountant rewarded for his brain-storm with a secret weekend with either Annette Funicello or Dean Jones. But perhaps I’m getting carried away.

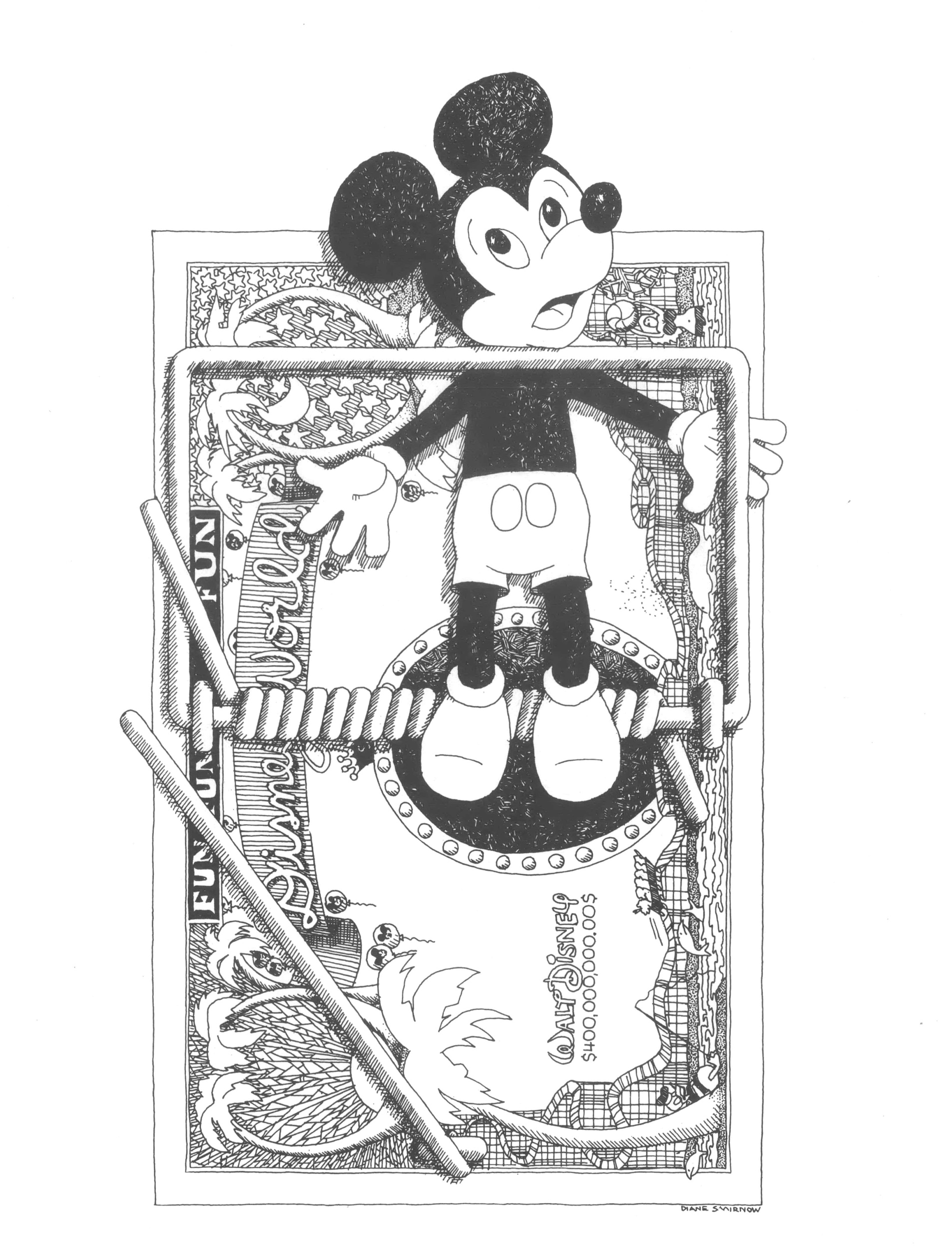

Whatever the origin, the simple facts remain that Disney spent roughly $400 million on the 27,400 acres that will eventually comprise not only the Magic Kingdom and its resort hotel (property of U. S. Steel Corp.), but an entire very-upper-middle-class “Experimental Community of Tomorrow” and, as ecology-minded Disney P.R. men will proudly (and it must be said, correctly) point out, a 7,500 acre green belt of woods and scrubland. Another simple, indisputable fact is that tourism became the single greatest component of the central Florida economy by the introduction of Disney World. A rather insane form of tourism, to be sure, dependent neither on history (the Dade Battlefield Museum on the site of the greatest Indian victory east of the Mississippi goes relatively unvisited for some reason), nor scenery (Disney World visitors rarely venture into the wild green belt), nor climate (air conditioning is a must in every public building).

The weird truth is that Disney World is an attraction simply because it is famous. Years and years of family entertainment pouring forth from Disney studios has left its dent on the American psyche. After all, who could forget Fred McMurray in “The Absent-Minded P.O.W.” or the animated classic “Bambi Versus the Do-Gooder Sierra Club?” Here again, I’ve gotten somewhat carried away, but you get the point: a trip to Disney World is an America Hegira, and not just for straight middle-agers. Indeed, Disney World makes a real effort to attract the hip young marrieds with a kid or two, not to mention the Mickey Mouse shirt-bedecked teenager, and often it succeeds.

It succeeds because almost all Americans are hooked on entertainment, whether they be the old folks watching hour after hour of TV or young kids absorbing hour after hour of abuse from second and third-rate rock groups. Whether you use Marxist or metaphysical terms, the analysis is, logically enough, the.same. Americans are so profoundly alienated from creativity, community, and realization, that they must be told when to have a good time. “You are now on vacation. You are going to a vacation resort. You will have a Good Time.”

To be sure, there are a few enjoyable attractions at Disney World. Perhaps the most promising from a societal view is the monorail from the truly awe-inspiring parking lots (named after Disney cartoon characters: “Good afternoon folks, welcome to the Magic Kingdom. Your parking lot is Goofy, I repeat, your parking lot is Goofy”) to the main entrance. The monorail is smooth, fast, and exceedingly comfortable. It even runs right through the lobby of the Disney-U.S. Steel resort hotel, which is shaped like an Aztec pyramid with two of its sides made of glass. Here again, though, media programming comes into play, since I’ll always be a sucker for anything that looks like one of those Rocky-Jones-Space-Cadet-Cities-of-the-Future. Being objective, which I can of course be, the monorail-hotel set-up is probably as good an opportunity as is possible to educate people from all over the country about the possibilities of mass transit. Indeed, the “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow” (EPCOT) will even have its own monorail system, a first that the Disney people are continually throwing back to ecologists.

In addition to all this futuristic stuff, a few of the Magic Kingdom rides are quite enjoyable. The Haunted Mansion trots out various cinematic techniques and even uses laser holograms to create one of the best spook houses ever. Monsanto Corporation utilizes a super-Cinerama 360-degree movie screen to provide a tour of America’s scenic wonders. (Monsanto, you may recall, is the company that makes all those wonderful “disposable” plastics and chemical fertilizers.)

Once you see those, however, and possibly listen to the West Indian steel band, you’ve exhausted the possibilities of real enjoyment, and are left with a seemingly endless procession of false-front castles and plastic plants, mechanical animals lurching unconvincingly from behind concrete boulders, and various rides that go around in erratic circles.

One of the most dispiriting experiences imaginable is to take one of these rides, say the Tom Sawyer steamboat, and watch the faces of your fellow passengers. Their faces are almost uniformly blank. They show nothing but a sort of mindless exhaustion as they listen to the Captain’s spiel and survey the concrete banks of the artificial lakes and rivers. Then you realize where you’ve seen that expression before. Of course! These people are “enjoying” the ride the same way they enjoy the Sonny and Cher Show. The programming has been. successful. They’re watching three dimensional TV!

“Go Rec Yourself, Man!”

Once you realize what this “recreation” is all about, you can begin to understand those clean-cut young employees. (Disney World employs nearly 10,000 people. The average age is 23. Hair length regulations for males are actually stricter than the Army’s). These poor benighted souls, many of whom travel up to 75 miles to and from work ($2.00-per-hour employees were not taken into account in the designs of the ideal city of tomorrow), have the same zombie expression as they go about their routines gaily

decked out in period costumes or cartoon character suits. A little probing and questioning reveals that these kids aren’t regular TV addicts. No sir, these are Freaks! “Don’t be put off by the hair, man, we stay royally fucked up all the time.” Yes, the Disney World work force is a haven for the numbed-out mutants of Woodstock Nation, the Qualude-kulture. As pointed out previously, choose your anesthetic according to your age and tastes, and an interminable semi-coma is the result.

All this would be of little importance if Disney World were just another facet of madness, but its paramount position in the developing tourist economy has made the Disney success story a model for eager developers and turned sleepy Polk, Orange, Lake, and Citrus counties into something entirely different from what they were only a few years ago.

Palmetto scrubland that once sold for $150 an acre now brings down $4,000 if it is available at all. Rents in Orlando, the closest city tp Disney World, have risen from a $75 average to $110-135 a month. Daily traffic on Interstate 4, one of the principal Disney access roads, has quadrupled. In its first year of operation Disney World brought in 1,600,000 guests. Seventy thousand people crowded the gates the day after Christmas alone. In two years Central Florida will have the largest concentration of motel rooms anywhere in the world.

In addition to the hamburger stands, gas stations, and motels, there is a plethora of new “attractions” that will probably finish off what Disney started: the conversion of all the highland-ridge area into the biggest amusement park on earth. Many of these attractions defy credibility, their brochures reading like they were written by Terry Southern and P. T. Barnum at 3 o’clock in the morning. Among the new tourist sites are:

□ Circus World: the permanent home of Ringling Brothers-Barnum and Bailey Circuses. Budgeted at $50 million, its main landmark will be a nineteen-story-high elephant, complete with elevators to the eyes.

□ Sea World: costing roughly $20 million, this will be the most real-life of the attractions, complete with leaping porpoises, coral reefs, and marine study activities. Located near Disney, it sounds like it might be worthwhile, which is a good bit more than you can say for . . .

□ Bible World: no, my friends, I’m not kidding. Do you think I enjoy writing this stuff? Complete with Palestinian village, murals of Christ’s life, and even an Israeli government pavillion; all courtesy of Fred Tallant, owner of Atlanta’s Stouffers Inn, and budgeted at a mere $7,000,000.

□ Johnny Weismuller’s Tarzan Land: roughly $25 million, no word if it features Johnny Sheffield or Maureen O’Sullivan. If they can recreate that scene where Weismuller jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge in “Tarzan Goes to New York,” I’m going! Perhaps Tarzan land was one reason for the premature death of . . .

□ Wild Kingdom: based on an idea paralleling Weismuller’s African park, Wild Kingdom first ran into trouble when Mutual of Omaha sued the owners for using the name of their Sunday afternoon television show without permission. Then the bills began piling up and, before anyone knew it, the grim laws of profit and loss had made their first kill among the hoard of central Florida side shows. There have been stories that the disgruntled ex-owners plan to simply let their collection of exotic African veldt animals run wild in the cypress swamp and cabbage palm hammocks they have grown accustomed to. Several antelope are already unaccounted for, giving rise to hopes of future visions of gazelles bounding through the orange groves.

Besides these large amusement complexes, there will be several novelty-type attractions, such as Vienna’s Lippizaner Stallions, in their new home outside Lakeland. A large hangar near Cape Kennedy will house the only model ever completed of the SST-supersonic transport. For a dollar or so, tourists will be able to take a quick tour of the plane they’ve already spent millions in taxes to build. A little to the south of the heart of the boom-zone, the Seminole Indians are begging to be allowed to continue usage of their traditional stronghold, the Big Cypress Swamp. The Indians have put forth a plan that would leave the huge virgin area untouched except for “wild animal farms” where good employment would be provided for the otherwise jobless Indians. These farms would raise alligators, deer and even such predators as fox and wildcat in natural surroundings. The animals would be reintroduced to hunted-out areas and permanent green belts around the cities. The plan is simple, yet truly progressive. It has received little but lip service in the state capitol at Tallahassee.

There, where the dollar signs still gleam in the eyes of legislators and lobbyists alike, only the most concerted and forceful action by the public can tear the government’s rapt attention from the siren-song of developers. But it has been done. Hugely successful “ecology referendums’’ in St. Petersburg and Sarasota have forced U.S. Steel and Florida Power & Light to give up their large shares of beach-front land as parks. In Sarasota, the referendum passed by nine to one, although the land in question, valued at $100,000 three years ago, had been given a sale price of $800,000 by Florida Power. A similar price was asked by U.S. Steel for Sand Key, and in both cases, a grumbling public gave its approval.

Anytime the electorate votes large taxes on itself, there must be some sort of trend in the making. The Attorney General, Robert Shevin, picking up on this environmental issue has declared all beach-front and marshland to be state property, a move that is already having far-ranging consequences. Unfortunately, saving the beaches will be of little help to central Florida. Here too, the people grumble about traffic, high costs, pollution, and general deterioration of living conditions, yet they also feel the pinch of economic pressures. There isn’t much more phosphate, and the day of the family farm is over, point out the hard-nosed realists. Besides, when mechanization finally reaches the groves, what else can all those migrants do but be waitresses and busboys?

It is hard for even the most resentful area resident to fight back against these arguments since in the end, there can be no real solution short of an environmentally sound, popularly planned, cooperative economy. These folks know that business is literally killing them, yet, as in most places, generations of conditioning send them to the barricades at the mention of alternatives to raw capitalism. The hope for building a real community rapidly fades as central Florida rushes to become a developer’s insane dream come true—one vast, manic Fantasyland.

Tags

Steve Cummings

Steve Cummings, a native of Florida, is a cultural historian and a member of the staff of the Institute of Southern Studies. A former organizer of migrant farm workers in Florida, Mr. Cummings now lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he handles promotional chores for Southern Exposure. (1974)