Folkroots: Images of Mississippi Black Folklife (1974-1976)

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 2, "Long Journey Home: Folklife in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Roland Freeman is a Washington-based photographer whose work has been exhibited widely in this country and printed in numerous publications throughout the world. The Mississippi Folklife Project, from which these photographs are taken, was supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Above: Ned Weatherby, fife maker, Franklin County, Mississippi.

The Mississippi Folklife Project grew out of the research and documentary efforts of black folklorist, organizer and poet Worth Long and myself for the 1974 Smithsonian Institution Festival of American Folklife. Our exhibit for that Festival is now permanently housed in the Smithsonian and in the archives of the State of Mississippi Department of Archive and History.

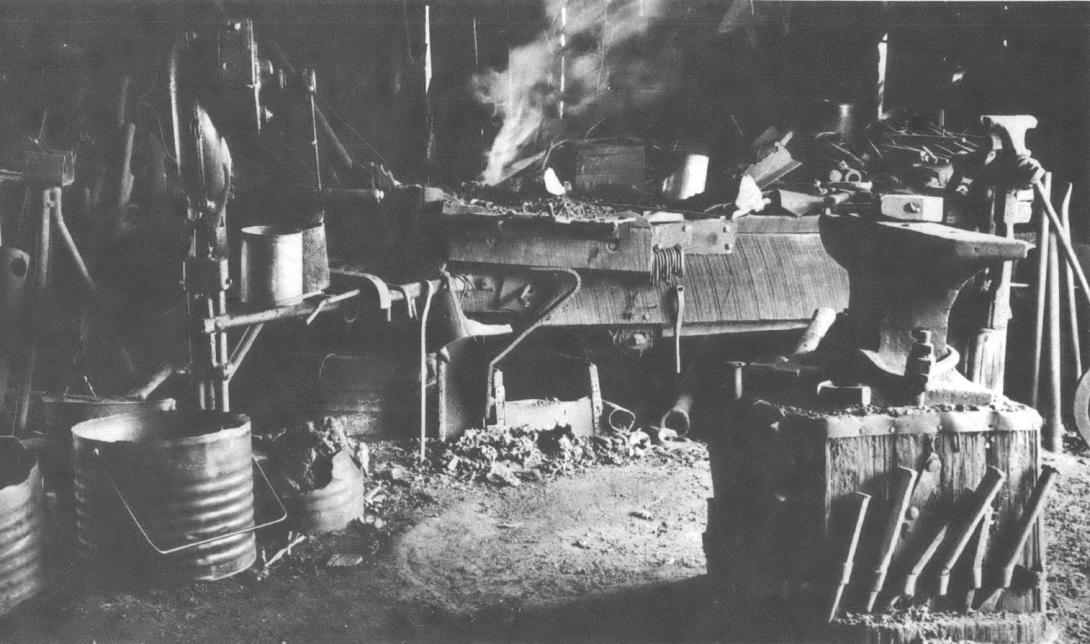

Through the research, photo-documentation and exhibition of the Project, we wanted to record and help preserve the fast-disappearing aspects of the black cultural heritage. We learned that most of the previous work done in Mississippi had focused mainly on the Delta region; we chose to start in the 11-county area of southwest Mississippi. In a relatively short period, we found a rich tradition of folk art, including quilting, basketry, blacksmithing, wood carving, moss and cornhusk weaving, crafting of musical instruments and children’s toys, clay and wood sculpture, gravestone making, yard sculpture, syrup and sorghum grinding. To the extent possible, I photographed all of these practices.

The deeper we got into the Project, the greater the historical significance it assumed. Time was literally the adversary of the culture and the people we were documenting. In the Project’s first two years, six craftspeople we have worked with have passed. And on Memorial Day, 1977, Julius Mason, a blacksmith from Roxie and a dear friend and constant source of wisdom and encouragement, passed.

Now, you have to look long and hard to find traditional folklife practices. Most people who know how to make baskets are becoming arthritic, or getting cataracts, or having trouble finding white oak needed to make the baskets. Where there were once blacksmiths serving every community, now there is hardly one active in every other county. Whittling and wood carving scarcely exist, and people who once made hand-sewn quilts now use machines. The time once spent in oral traditions is now consumed with television watching. The ability to craft most things that one needed, and of passing that skill on to the next generation, has lost its status and respect, especially among the young. Thus, when the existing craftspeople die, with them will go many of these practices. Understanding that dynamic was the main reason we started and continued the Mississippi Folklife Project.

We are presently in the Project’s exhibition phase. A major exhibit of photographs and selected artifacts from the Freeman Collection of the Project runs from Sept. 6 to Oct. 16, 1977, at the Mississippi State Historical Museum in Jackson. Entitled “FOLKROOTS: Images of Mississippi Black Folklife (1974-76),” it is the first photographic exhibit by a black photographer mounted by the Museum. From Jackson, the exhibit goes to Alcorn State University in Lorman, Miss., then to the annual meeting of the American Folklore Society in Detroit, and to Indiana University, and then on an extensive national tour.

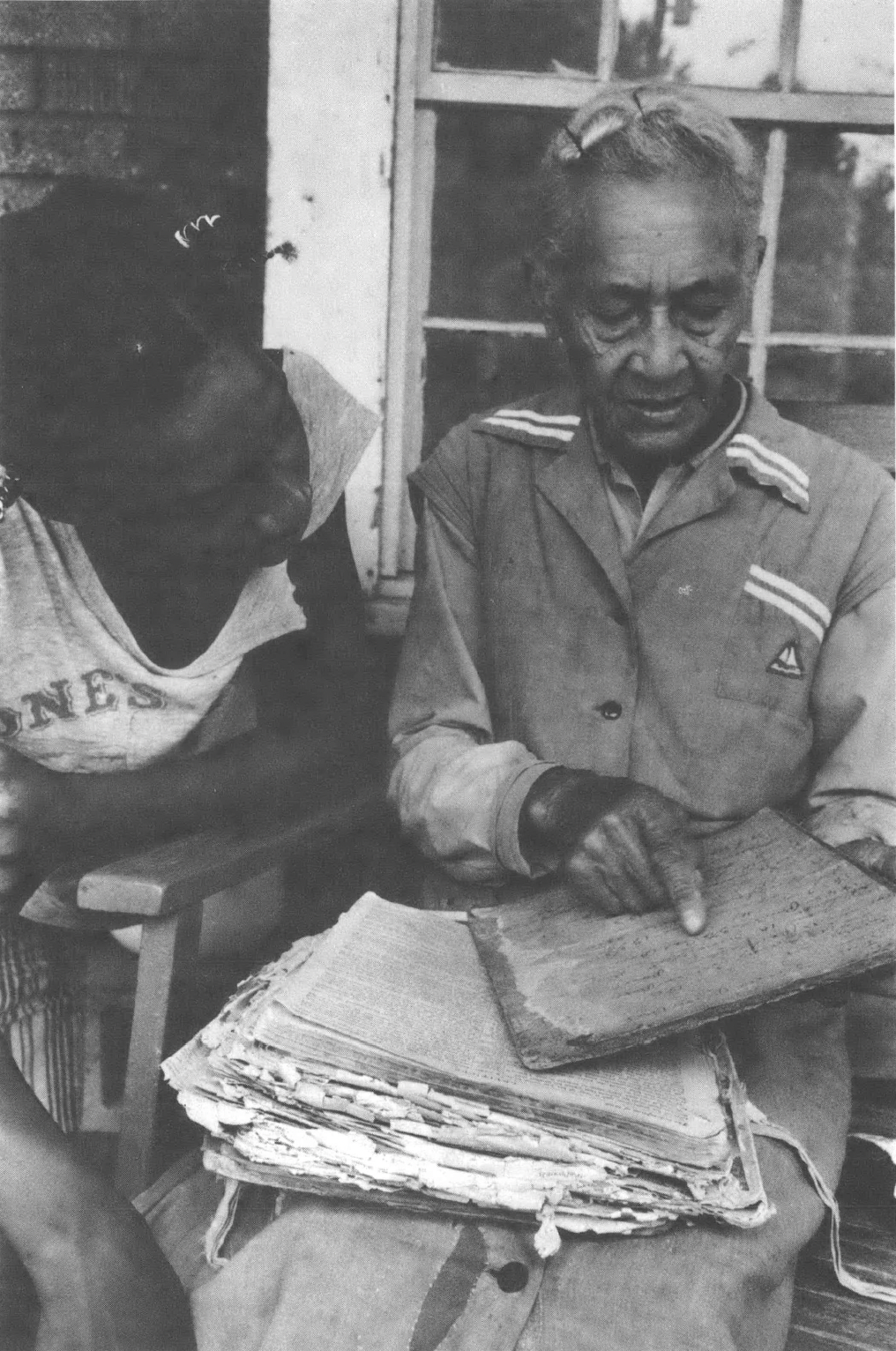

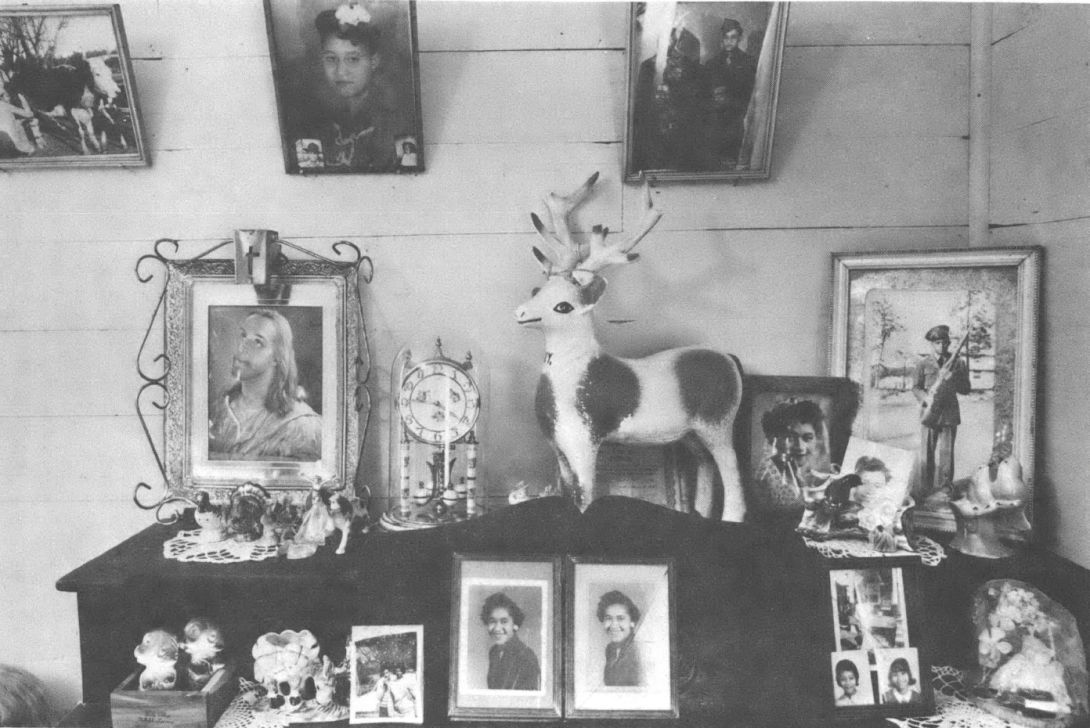

Mrs. Annie Mason, quilter, Franklin County, showing her grandson how the family has traditionally recorded names and birth dates in their Bible. Of all the people I’ve met during the project, she has one of the best family histories of photographs and other memorabilia. She takes great pride in saying she has a grandson in California who wants to preserve her house as it is, as a family museum, when she has gone on.

“I started working for a colored man named Mr. Gene Prophet in his farm shop when I was eight years old. By the time I was 10, I was sharpening plows for a nickel. At 14, I went to work for a white man who had a grist mill and blacksmith shop, and worked for him 22 years. I opened my own business right here in 1939 and continued until 1976. I made everything from wagon wheels to dog irons, and when lumbering came in, I made all kinds of equipment for them, and even had as many as five men working for me at one time. Now I’m just about like all those old-time things. I’m about played out. I had a stroke a little while back and still got a pain in my chest. I’ve been breathing this coal smoke too long. It’s time for me to retire and let the old fire just burn out.” — Julius Mason, (1902-1977), blacksmith, Franklin County

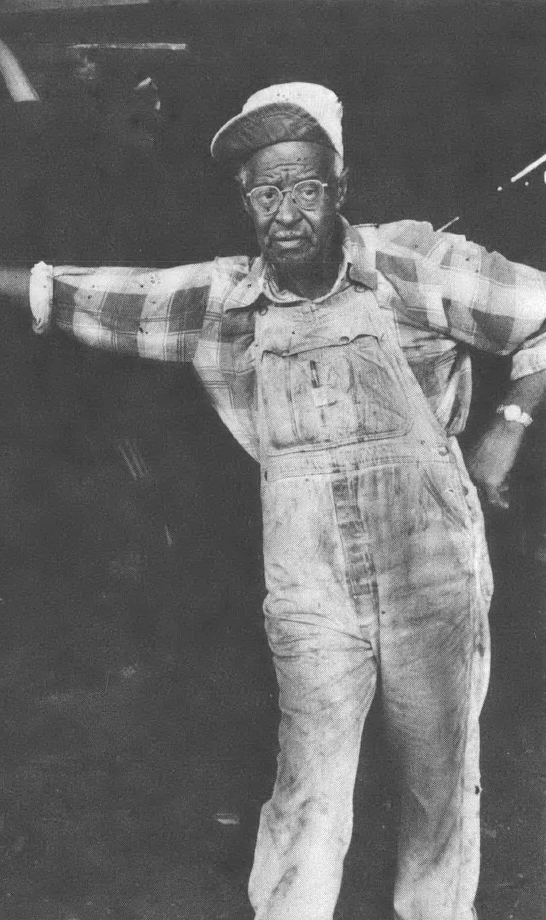

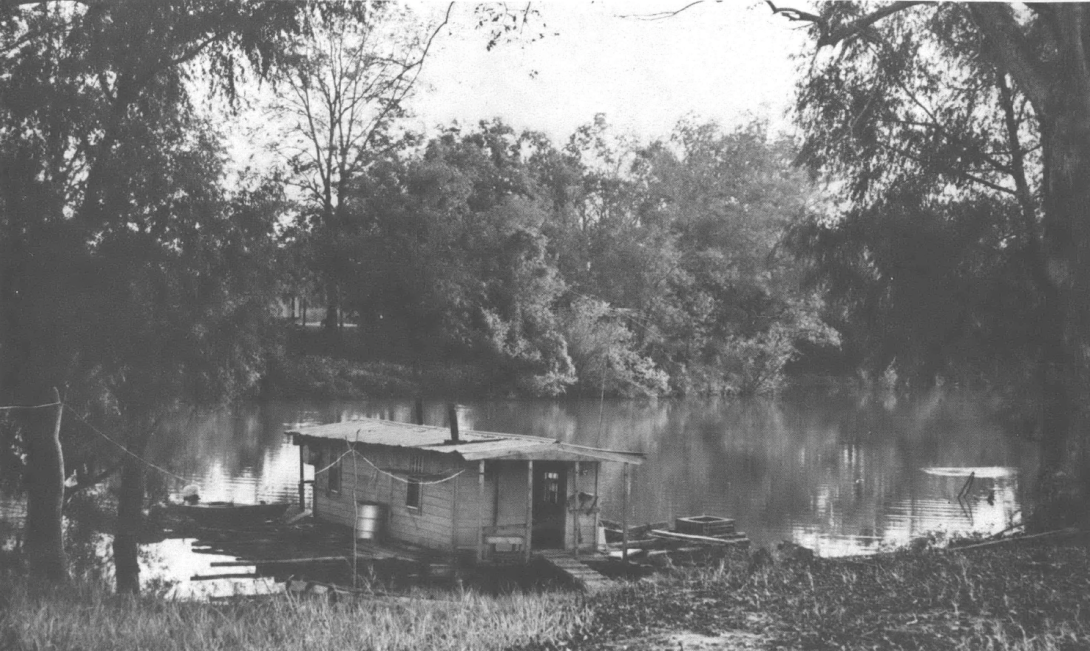

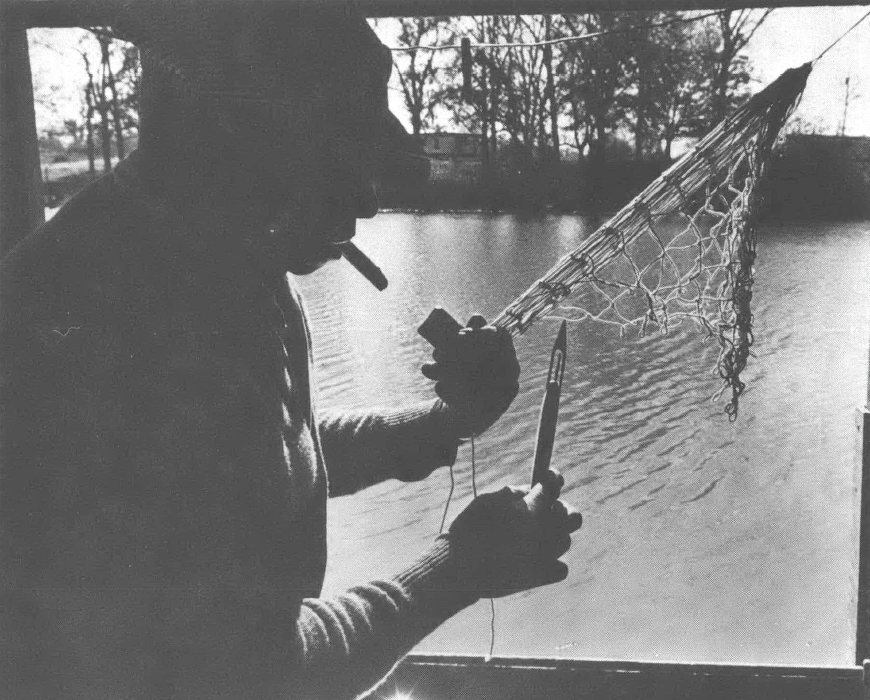

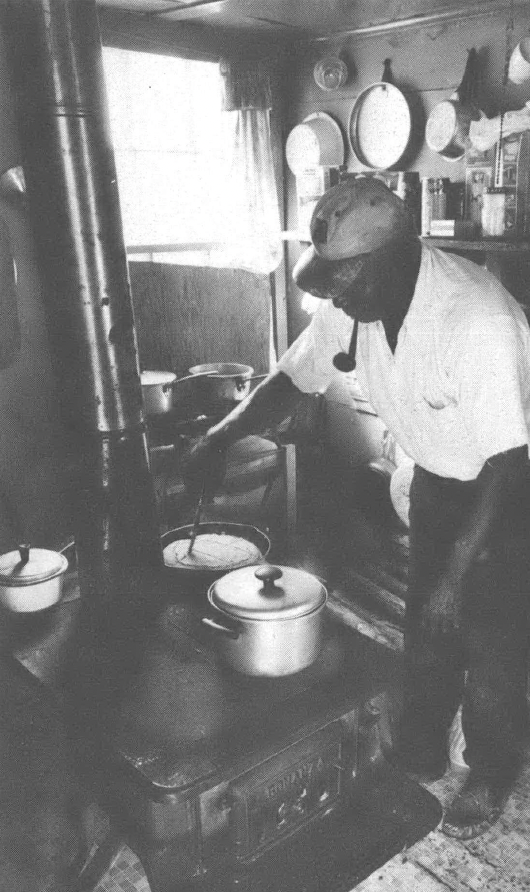

“My mamma and daddy brought me out here round this river and lake when I was about seven. I done all kinds of work in my life, everything from raising cotton to public work. I worked all up and down the Mississippi River between here and New Orleans. I’ve been called all kinds of nicknames, from ‘barrel house’ to ‘rough crawler.’ “Now I just fish here in the old lake. Once there was an awful lot of colored people all around here, but when those last high waters came in ’72-73, just about everybody left here. I got cables hooking my house to them trees, and when the water rises, my house rise with it. And when the water went down, I’m still here. Old bossman said I could stay here as long as I wanted to.” — Henry Butler Fields, riverman-fisherman-netmaker, Adams and Wilkinson Counties

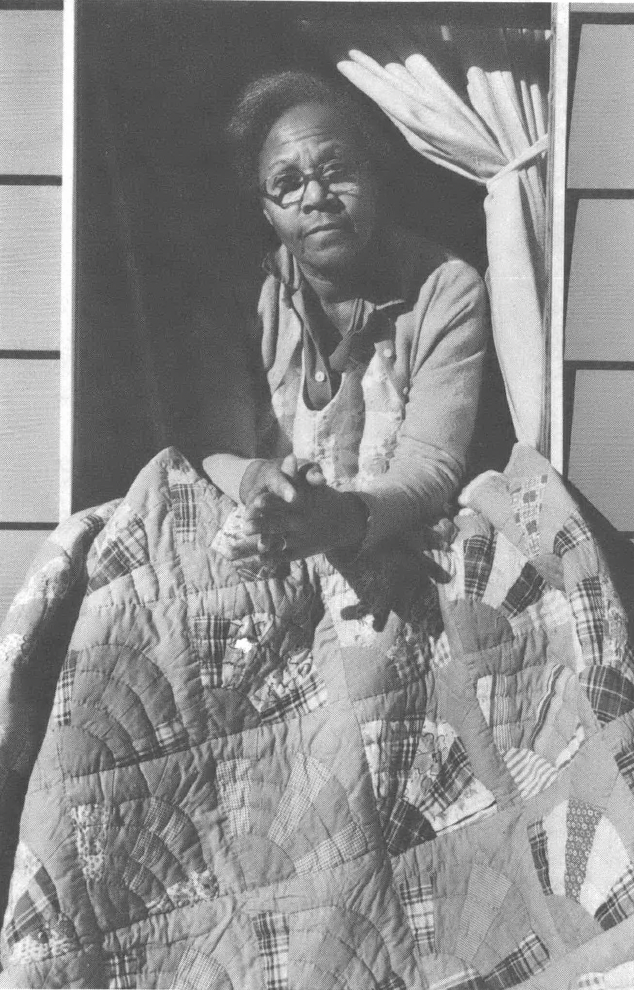

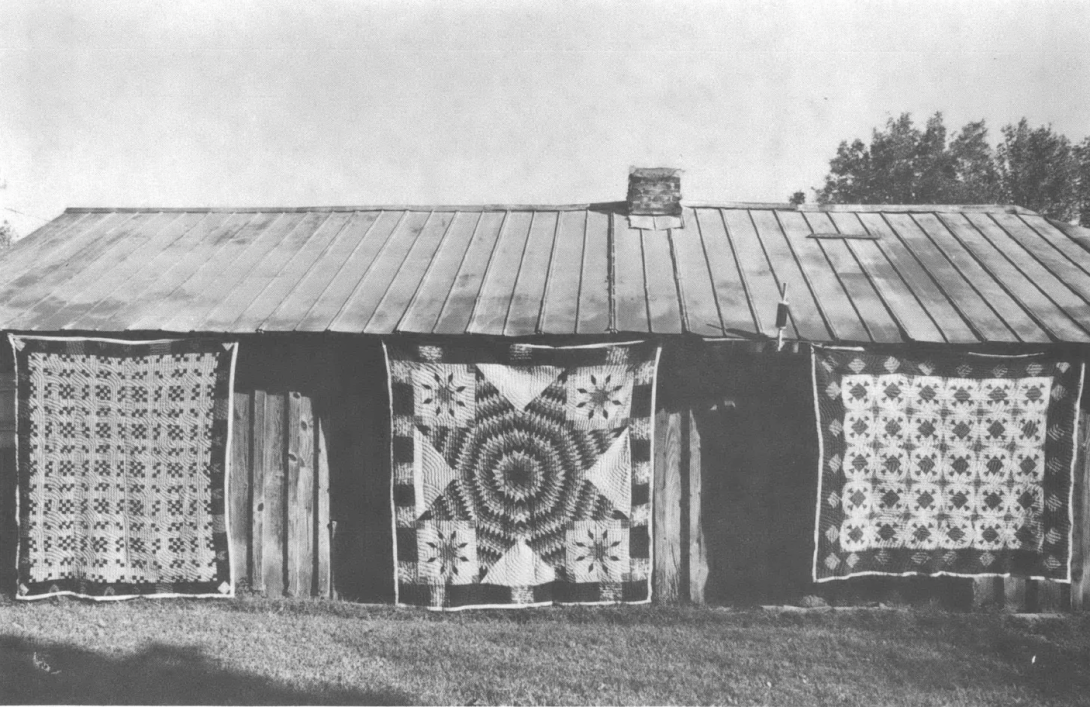

“I started piecing quilts when I was seven or eight years old. First thing I pieced was a little nine-patch, and Papa made the biggest fuss over it you ever saw. My grandmama quilted, my mother quilted and two of my three daughters, Annie and Emma, quilt. Course they do that fancy piecing and quilting. I don’t do any more quilting. My hands won’t take it, but I can still piece up one of the prettiest spreads around.” — Mrs. Phoeba Johnson, 94, quilter, Wilkinson County

Mrs. Johnson’s daughters, Mrs. Emma Russell, Mrs. Annie Dennis and Mrs. Dennis’ house and quilts.

Tags

Roland Freeman

Roland Freeman is a Washington-based photographer whose work has been exhibited widely in this country and printed in numerous publications throughout the world.