This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 4, "Generations: Women in the South." Find more from that issue here.

In 1956, Pauli Murray published Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. Like Alex Haley’s Roots, this triumphant saga of four generations served notice that black Americans had begun to recover and define their own history. Murray’s book focused on her grandparents, Robert and Cornelia Fitzgerald, who embodied in their own lives the tensions of a biracial society. Cornelia was the daughter of a slave raped by the son of a wealthy North Carolinian. Robert was the offspring of a loving marriage between a mulatto coachman and an illiterate white farm girl. The couple met when Robert, after fighting in the Union Army, came South to open a school for ex-slaves. When the dismantling of Reconstruction and the re-establishment of white control forced him to close the doors of his beloved school, Robert moved his family to Durham, North Carolina, a New South tobacco town. There he made a sparse but respectable living as a bricklayer.

Robert’s love for teaching, however, lived on in his oldest daughter, Pauli Murray’s Aunt Pauline. She was, she later told her niece, “practically born and bred in a school house with a piece of chalk in my hand.” Robert carried her to his school when she was only two; at four she could read and write. Nine days before her fifteenth birthday, with her hair up and wearing a long, grown-up dress, she passed the county teachers’ examination. Although so fair she could have crossed the color line, she remained what was known as a “race woman,” making her work as a teacher her contribution to the black freedom struggle.

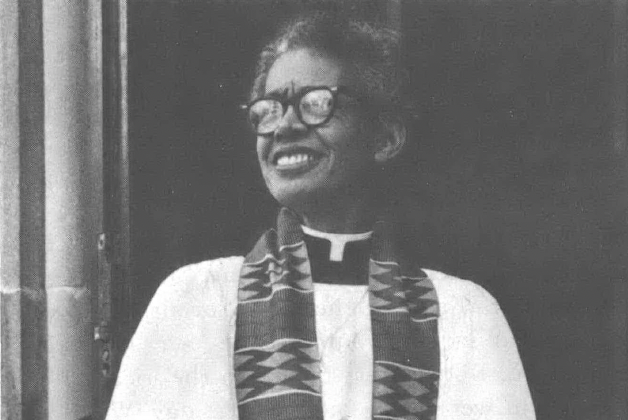

Now 66, Pauli Murray has continued the battle for dignity and self-expression which is her family heritage. In the process, she has won distinction as a civil-rights attorney, a feminist leader, a writer and a poet. On January 8, 1977, she became the first Negro woman ordained a priest in the 200-year history of the Protestant Episcopal Church.

Murray began her career in the 1920s as a “New Negro” poet of black identity and protest. In the ’30s, she plunged into the labor movement. Gradually, however, the logic of events pushed her toward the law.

In 1938, the University of North Carolina, heir to the estate of Murray’s own white ancestors, turned down her application for graduate study because she was black. The following year, she was jailed in Petersburg, Va., for resisting segregation on an interstate bus. The turning point came with the famous Odell Waller case, in which a black sharecropper was unjustly sentenced to die for the murder of his white landlord. As a field secretary for the Workers Defense League, Murray traveled throughout Virginia raising funds for the defense. “I told myself,” she remembers, “that if we lost his life, I must study law. And we lost his life.”

As a writer and an attorney, Pauli Murray has raised a singular voice on behalf of both women’s liberation and black autonomy. She was a co-founder of NOW, and, as an ACLU attorney, she contributed to the precedent-making court decisions holding that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applies to discrimination because of sex. She served as a Senior Lecturer at the Ghana Law School and, from 1968 to 1973, as Stulberg Professor of Law and Politics at Brandeis University.

In 1973, she abandoned her legal career for the church. As a candidate for the priesthood, she found herself in the midst of a conflict as bitter as any that had gone before. Yet, for her, ordination represented not so much a milestone in the struggle for women’s rights but a new phase in a long search for “reconciliation and liberation.”

The story below was selected and edited by Lee Kessler from the rough draft of a chapter from Pauli Murray’s new book, tentatively called The Fourth Generation of Proud Shoes (forthcoming from Harper & Row).* Like the first volume of her family history, Fourth Generation is more than a record of accomplishment. It portrays with great warmth the sorrows and pleasures of everyday life on the edge of the color line, the sustaining role of kinship bonds, the tradition of self-sufficient women, and the faith in education which made it possible for the Murray family to “walk in proud shoes.” The story begins in 1914, when, after the death of her own mother, Pauli Murray came to Durham to grow up under the guidance of her Aunt Pauline.

* * *

Aunt Pauline’s decision to adopt me was a significant departure from her traditional role in the Fitzgerald family. I learned afterward that she had taken the step in the face of dire warnings and admonitions from friends and relatives. As the oldest of six children of a blind father-and high-strung mother, she had been the workhorse, the person to whom everyone looked to keep things going through all emergencies; her parents’ wishes and needs had been paramount. She had escaped this role briefly around 1899 to marry and embark on a life of her own, but this bleak venture was marked by an unrelieved struggle for existence and by the loss of her two children in infancy. The marriage itself foundered on an issue of principle.

The future seemed promising enough when she married young, blond, blue-eyed Charles Morton Dame, fresh from Howard University Law School. But they had not reckoned with the formidable racial barriers facing colored men who took up the practice of law. Racial lines which had blurred during Reconstruction were now being drawn ever tighter by the segregation laws enacted by the Southern states in the wake of the Plessy decision of 1896. The best young Dame could do was to earn a few dollars here and there surreptitiously writing wills and deeds for white attorneys, supplemented by his wife’s meager earnings as a teacher. They moved from Virginia to West Virginia in search of opportunities, but Dame seemed unable to establish himself at the bar.

Some of the white men for whom he worked said flatly, “Look, Dame, you’ll never get anywhere as a colored lawyer. You’re as white as any white man and you’ll have a better chance if you cross the line.”

During the first half century after Emancipation, thousands of near-whites exercised this option to escape racial oppression, and the temptation to end a grubbing existence finally overpowered Charles Dame. He announced his intention to his wife and tried to persuade her to join him in the proposed venture. She herself looked indistinguishable from a Caucasian and the two of them would have had little difficulty fading into the white background.

Aunt Pauline’s refusal brought an end to their marriage. Charles Dame disappeared from her life and there were rumors that he became a very successful lawyer in a neighboring state. She returned home to slip into her accustomed harness and everyone took it for granted that she would have no further life of her own. Thus, it was with some consternation that her relatives and close friends viewed her first step toward independent action. They warned her that taking a three-year-old

child was too great a responsibility for a lone woman of 43 who already had two aging parents.

“It’s a mistake to raise somebody else’s child, particularly a girl,” they said. “It’s too full of heartaches; she’ll bring you nothing but trouble.”

Their concern was well-founded. My arrival would create many practical problems, for the Fitzgerald household included my grandparents, who were frail and in their late seventies, as well as Aunt Pauline and Aunt Sallie, her unmarried sister of 36. Both sisters taught in the local public schools and were away most of the day. What was Aunt Pauline to do with me while she was away at school? It was too much to expect my grandparents to cope with an active mischievous child. And there were no nursery schools for working parents.

Moreover, her appointment to the city system was more than a full-time job. It required the dedication of a saint. Aunt Pauline rose at five every morning and arrived at school before seven thirty. She came home late in the afternoon, prepared supper, and then returned to night school to conduct literacy classes for the hardworking parents and grandparents of her day-school pupils, if a child was absent, she visited the child’s home after school to find the reason. She was expected to attend all community gatherings in addition to teachers’ meetings and parents’ meetings. On Sundays she usually went to church twice: morning service at her own St. Titus Episcopal Church and evening service at the neighborhood Second Baptist Church which many of her students and their parents attended.

For all her stolid exterior, Aunt Pauline had a timid streak and shrank from contention. She gave in on many issues to keep peace in the family and in most of her decisions she deferred to her parents’ wishes; but on the issue of my future she was resolute.

There were obvious reasons for her decision, of course. I was her namesake, her godchild, and it was my mother’s last request that Aunt Pauline have me. I also filled a void left by the deaths of her own children. But I think there were other reasons which she could not put into words. She was reticent about expressing her inner feelings to adults, but she had no difficulty communicating with small children. She had the unerring intuition of a great teacher. She taught not merely to impart knowledge but to build character and shape the future. Whether a child was pliable and responsive or wooden and inflexible, she sensed its possibilities. She envisioned the finished product, the fine grain of wood beneath a rough and splintered exterior.

So, in spite of family objections and anticipated hardships, Aunt Pauline brought me to Durham to live. If she ever had misgivings about this risky venture, she never voiced them. Aunt Pauline’s sturdy ally but strong competitor in her new undertaking was her younger sister Sallie, also a teacher. Seldom were two individuals so different, yet so fiercely loyal to one another. Aunt Pauline was intensely practical, a woman of few words who seldom smiled. She was kind and just, but strict; she never allowed me to dawdle over my chores or to evade responsibility for misdeeds. She possessed a

methodical mind and plodded through the most difficult task until it was done. Aunt Sallie was imaginative and entertaining, with a contagious laugh and an endless repertoire of engaging stories, but she tended to be disorganized and followed a pattern of stops and starts. She had great intellectual curiosity, sang, played the piano, read widely and was a great conversationalist. Aunt Pauline sang a little off-key and had less artistic bent. I could always talk out my troubles with Aunt Sallie, but in any emergency which required action I automatically turned to Aunt Pauline. Their contrasting personalities were my strongest maternal influences and I grew up absorbing characteristics of each.

My schooling began in a somewhat unorthodox manner when I was around four or five. Since Aunt Pauline was determined not to burden my aging grandparents with caring for me, she decided to enroll me in school. She taught at West End, a six-grade public school for colored children housed in a weather-beaten two-story wooden building across the road from the long, low Liggett and Myers tobacco warehouses near the Southern Railroad tracks. What a contrast it was to the nearby white children’s school with its fine brick building and green lawn. West End was so rickety that you could hear the wind howl through on stormy days. We had no playground equipment or lawn either, just barren clay ground.

Although West End had no kindergarten, it had three levels of first grade. A child normally progressed from one level to the next, and it usually took three years to reach second grade. Aunt Pauline taught the highest section, 1-A, but she secured the principal’s permission to place me with other beginners in Miss Hattie Jenkins’ class.

My career in class, however, proved to be short-lived. Within a few weeks my presence stirred up a controversy among other parents who complained that if “Mis’ Dame” could put her child in school before the legal age of six, they had the same right. Mortified, Aunt Pauline immediately withdrew me from formal enrollment, but having no alternative she continued to bring me to school with her every day and kept me in her own classroom. The older children adopted me as a class mascot and under Aunt Pauline’s watchful eyes, I was permitted to sit with them at their desks and to look on while they recited. But in order to avoid criticism, she did not allow me to participate in class games or to be anything more than an onlooker.

The most common classroom game in the lower grades in those days was one in which children performed their reading and spelling lessons standing in line side by side. When a child made a mistake, the next child who recited correctly took his place. The line was constantly changing, the objective being to reach the head of the class. Children who misbehaved forfeited their places and were sent to the end of the line. It was a harsh game for slow learners, but the faster learners loved it.

Toward the end of the school year Aunt Pauline was surprised to see me standing in line with the

other children, something she never allowed me to do. In spite of her sternness, she was gentle with children, and I never knew her to single one out for humiliation. She simply ignored me and was about to pass over me to the next pupil when she heard me sing out, “I can read, Aunt Pauline!”

Without waiting for her to reply, I seized the book of the child next to me and began to read out loud. When the class was over, Aunt Pauline called me to her desk. She reached in her drawer and pulled out a book I had never seen before.

“Let me see you read this book,” she said. She had assumed that my earlier performance was one of mimicking the other children and speaking words from memory. When I read the new book without making a mistake, she realized that all the time I had been in her class I was learning whatever she taught the others. From then on study was as natural to me as breathing and the classroom became my second home.

One of Aunt Pauline’s big problems was how to fill the bottomless pit in my stomach. She could not understand how a small child could eat so much and stay so skinny. I had three passions — beef steak, molasses, and macaroni and cheese. Macaroni and cheese we ate almost every Sunday and molasses was cheap, but steak was usually beyond Aunt Pauline’s pocketbook. She would buy a few ounces, just enough to flavor thick flour gravy, and use hot biscuits as a filler.

In those early years I rebelled against Aunt Pauline’s discipline only over food. Once we were invited to dinner at the home of Dr. Charles Shepard, brother of the Negro college president, Dr. James E. Shepard of North Carolina Central University. Aunt Pauline admonished me to be on my best behavior. All went well at the dinner table until I asked for another piece of meat. Aunt Pauline said no, but I insisted. “Let her have it, there’s plenty,” Mrs. Shepard said, but Aunt Pauline believed that good discipline required firmness and said that I had to learn that “no” meant “no!” I continued to beg for meat. Finally, she threatened to take me down from the table and give me a whipping if I asked again. She almost never whipped a child, and to her, a whipping was a drastic measure. But her warning had not the slightest effect. I stubbornly clung to my request.

The inevitable happened. Aunt Pauline took me into a room and gave me one of the few whippings in my life. I was in disgrace when we came back to the table, but my first words were, “I want more meat, Aunt Pauline.” I didn’t get it, of course, but the incident made such a deep impression on me that I always saved the meat on my plate to eat last.

Aunt Pauline’s method of hometraining was a remarkable blend of firm discipline and freedom to choose, though I had to live with the consequences of my choices no matter how bizarre they might be. Once she let me pick my winter hat and coat, and I decided on a chinchilla coat with a red flannel lining and a funny little Tyrolean hat from the boys’ department. This I had to wear — it was my choice — no matter who laughed.

This unorthodox approach collided with the more traditional methods used at school, and during the five years I attended West End, Aunt Pauline was in the unhappy position of being both a parent and a colleague of fellow teachers who found me too self-assertive, “too fast” and “too womanish” for my own good. She seldom escaped a detailed report from them of my slightest misdeed. A teacher’s child was expected to be a model of good conduct, not a ringleader of mischief. They never complained that I was insolent or deliberately disobedient, but that I had too much energy for one child.

My teachers used various schemes to keep me under control. In the second grade, my Cousin Ethel Clegg, whom I adored, felt that she had to be extraordinarily severe with me so that other children would not complain of favoritism to her relative. She made me sit apart from the class in a corner desk near hers in the front of the room where she could keep an eye on me. It was the lingering remnant of the “Dunce Stool” and Cousin Ethel could not have contrived a more embarrassing symbol of disgrace.

Miss Martha Hester, my third grade teacher, would take me along with her whenever she left the room on an errand, explaining to other teachers that she dared not leave me behind or I would have the class in an uproar when she returned. On these occasions I would stand wishing I could shrivel into a speck of dirt and disappear between the floorboards.

My worst ordeals at West End came in the fourth grade under Miss Louise Bullock, a massive woman who ruled by naked fear and would cuff a child without warning. Once when we were standing in line, she thought I had created a commotion. Without saying a word she slapped my face so hard she left the red print of her fingers on my cheek for all to see. My problems with Miss Bullock were complicated by the fact that, along with Christine Taylor and Lucille Johnson, I was among the three “lightskinned” pupils in a class of darker hues, a minority within a minority. That Lucille and I also had parents who taught in the school system did not add to our popularity. We seemed to be the prime targets of Miss Bullock’s ire.

One of our forbidden pleasures that year was sneaking off to Mr. Jim Elliott’s little grocery store a few doors from our school building during school hours. Mr. Elliott kept a big barrel of vinegar pickles in the back of his store which he sold for a nickel each. Our supreme joy was to wedge ourselves between rows of piled up cans and cartons, fish around in the barrel with a long-handled fork for the biggest cucumber we could find, then buy a penny’s worth of sour balls, bite off the end of the cucumber, insert the candy and suck the sweet and sour combination until the pickle gradually disappeared. When Miss Bullock caught me one day with a half-eaten pickle in my desk, she thrashed me before the entire class.

After one of these episodes, Aunt Pauline would look at me steadily through her rimless glasses, a sadness in her eyes and deep disappointment in her low even voice. She would sigh when I brought home my report card each month with a string of A’s in scholarship marred by the first column labeled “Conduct” which wavered from A to D. I would feel more remorseful than if she had given me a second whipping because I knew that I had brought her disgrace.

Those years of being a high achiever in scholarship and a low achiever in deportment made me ambivalent about myself. I desperately sought approval and my inability to measure up to my teachers’ expectations made me feel there was something wrong with me.

I also felt different, both rooted and alien, because I could not talk as naturally about my

parents as other children did. It must have been my need for a visible parent which finally led me to ask Aunt Pauline if I might call her “Mother.” To her credit she tried to fill my need while being very careful not to usurp my own mother’s place in my memory. She did not try to shield me from painful truths and she answered endless questions about my family. So strong was the fusion of need and reality that I lived with two symbols of motherhood. On Mother’s Day when people wore flowers in tribute to their mothers, I could not decide whether to wear a white flower in memory of my mother Agnes or a red flower in recognition of Aunt Pauline. It was characteristic of my way of resolving dilemmas that I wore both kinds.

Copyright 1977 by Pauli Murray, published by permission of the author.

Tags

Pauli Murray

Among Pauli Murray’s publications are Dark Testament and Other Poems (1970); States’ Laws on Race and Color (1951); and “The Liberation of Black Women,” in Our American Sisters, edited by Jean E. Friedman and William G. Shade (1973). See also Pauli Murray Interview, Feb. 13, 1976, Southern Oral History Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (1977)