"A Free Platform"

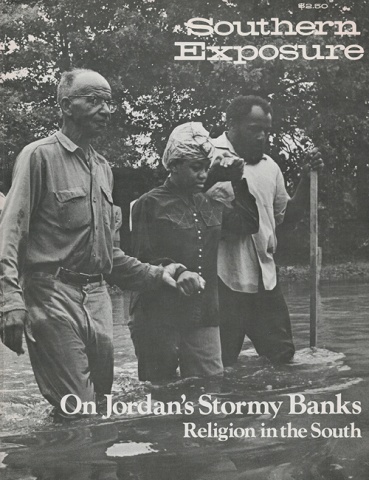

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

Rev. Joseph L. Roberts, Jr., is the minister of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church on Atlanta's Auburn Avenue. It is a symbol of the movement for black equality and of its most powerful, respected, and charismatic leader. Older church members remember holding Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on their knee when he was a child, it was in the basement at Ebenezer that he helped form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and it was here that his body was brought home for the final time in 1968. Today, Ebenezer still serves its local Atlanta congregation, but it has also become a shrine to thousands of tourists who visit each year. It stands now within the new complex of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Social Change.

Joe Roberts is excited by the possibilities and the challenges of his ministry at Ebenezer. He feels that precisely because of its historically prophetic role, the black church can remain the "focal point where political, social, economic, and theological issues can be discussed."

I graduated from seminary in I960 when integration was still big. I was the pastor of two integrated churches —trying to help people live together as Christians—and almost denigrating the black experience in so doing, compromising by allowing the church service to be what I had learned in seminary: a modern version of the English Puritan worship of the 17th and I8th century. And then sort of disavowing who I was as a black person.

When Stokely Carmichael and others broke forth — Dr. King did it, but Stokely did it more dramatically because he said we've got to liberate the turf we occupy—that made me wonder what I was doing in a predominantly white denomination. Was I really selling my services to perpetuate a basically racist system, or was I in a ministry with which black people could identify? To be honest, it caught me. It resonated with something that was deep in all of us, and I think we were able to sort of move on from there.

When I was pastoring in New Jersey, I was involved in the denominational hierarchy in New York as a volunteer on a number of boards and agencies actively involved in church and race. The cities were going up in smoke; Stokely had given the black power sign in '66, and the National Committee of Black Churchmen had met in New York to sanction the validity of the black experiment. I think the black church, at that point, was trying to put some religious sanction on blacks calling for separate black power—before they integrated—believing that it was impossible to integrate an elephant with a mouse. I was in the business of trying to interpret to conservative black congregations why the whole business of black identity was a valid pursuit and how it wasn't antithetical to the Christian gospel.

In 1970, I was called to do Church and Society for the Presbyterian Church, South, and I decided to give it a try. It is a church where one half of one percent of its constituency is black, and I was the highest black bureaucrat; naturally I had the church and race portfolio. I insisted when I came that I have some money to do some social change strategies.

We were right in the sweep of all the stuff that Nixon was talking about when he tried to get the Department of Commerce to push black capitalism. I had some feeling of satisfaction because I was in the train of James Forman (author of the Black Manifesto, demanding reparations from the white church). We were getting white people's money and giving it to black folks. I have some real questions about that now. In the first place, we did not have enough money to make black entrepreneurs successful. But I think the basic tragedy was that we never questioned the assumption of capitalism. We just said we are going to replace white entrepreneurs with black entrepreneurs and never did deal with the moral issue.

I

I traveled for the church in 16 states; I would be off maybe once or twice a month. A mutual friend introduced me to Dr. King, Sr.; he was getting older, and said, “I need a little help now and then. Can you help me?” I said, "It would be an honor to preach at Ebenezer.” And that's how i started, i preached for about a year when I could and just got close to the congregation. One evening he just got up in a church meeting and resigned and told them, "I know who you should choose for your successor," and put my name forward. They unanimously elected me.

I feel it is an honor for me to come here, and then I also feel, not being overly modest, uniquely prepared for the ecumenical thrusts that are needed now. I wouldn't have come here if it were just another local church. I felt this was a chance to give some personification to the ecumenical movement; I mean what difference does it ultimately make—all this noise about denominations? I saw it also as an attempt to speak out on some international issues that are very close to me, involving the violation of human rights in Latin America and Africa in particular. Those two places concern me. I knew here I would be able to have a platform to actually say something and do something.

Because this is a tourist spot, I have the opportunity to make it more than a tourist spot, to heighten the consciousness of a lot of people about the problems of Third World folks, and get them to see how they might affect those problems. We had 1,400,000 tourists last year. From April through October, they came by reservation. I would say easily a third of the congregation are tourists in the summer.

Then, to a very real extent, this place will always be something of a shrine to black people and it is very important for us not to let it die with Dr. King, but to at least make it the place where the issues are looked at and where folks can gather to do something about them.

Now I haven't romanticized the position. I don't plan to lead anybody down the street. I am not Dr. King, and I do not presume to be. I respect him for who he is and realize that he comes along once in a millennium. But there are still a lot of things to be done. Ninety percent of all black Protestants in this country are in Baptist or Methodist churches. The black church still has what the white church has seldom had because it didn't need it—the reputation of being the focal point where political, social, and economic as well as theological issues can be discussed openly. Here I have a free platform. We lay out Angola; we criticize the state legislature for cutting welfare, and with no apologies. In the Presbyterian Church you had to tip softly on some very, very fragile egg shells because some of the folks had the misconception that all welfare folks are lazy and black. But you don't have that here.

I think the black church has been far more political and theological, even when it did not realize it. The spirituals had theological as well as political overtones. "Let us break bread together on our knees." That had to do with when a meeting was going to be held for taking off; the line "when I fall on my knees with my face to the rising sun," meant "in the morning, on the west side of the river is where we are going to take off." The old spiritual "Wade in the Water" had to do with slaves escaping and hitting the water to kill the scent when the dogs came after them.

Always there was this feeling that another message was being carried. What the black preacher was trying to do was deal with the fact that black people had no place where they were called sane, or no place where they had any dignity. I've got women in my congregation who go out five days a week wearing white uniforms, which says they are nobody, but when they dress on Sunday morning and come to Ebenezer, they are dressed to kill, naturally. This is the only place where a nobody can be somebody. It doesn't matter to the people where they work who they are, and the uniform is a sign that they do not belong in that community, that they are only there to serve it. But when they come here, it means something altogether different.

How do you get your dignity? That is what black folks talk about; white folks didn't need to talk about that because, for better or worse, by whatever means necessary, they were able to get some power, and that was power over somebody else. But the struggle of black folks is how to get equality. And that is where this church has been very meaningful, from the time King supported the bus boycott and Rosa Parks.

II

I basically think the white Protestant Southern church serves a constituency that is interested in maintaining the status quo, and therefore is far more guarded and far more ambivalent than the black church. In contrast, the black church is not afraid of being prophetic because it's been on the bottom. In this congregation, people will applaud a strong statement for justice, will break out in a round of applause. If I said the same things in a white church, I would be fired. If I talked about multi-national corporations, if I talked about ITT and Chile, if I talked about Brazil and the heinous things going on there and, as I did, call for missionaries to leave because they were really perpetuating a bad system, I would just be out on my ear. That is the real difference; the white congregation is too tied in with the white power structure to be critical of it. The danger for black people is that they are tempted to pick up some of those same values.

The black church has always been willing to admit that a person is not only cerebral but visceral. The white church has not. From the Greeks on, the white church has made a bifurcation between mind and body, so that everything that didn't fit into western, rational, logical categories could not be dealt with. So, how do you deal with a feeling? The white church just isn't able to deal with that. The psychiatrist is, and so you get psychiatry and religion as twin ministries. A person goes to a white church and stays for one hour on Sunday morning bleeding inside and then beats it to the analyst that afternoon or all the next week to try to get it together. The black church always was able — sort of in the Hebraic concept — to keep body and mind together. For example, I had one guy who just said one Sunday morning, "In spite of everything that has happened to us, I'm so glad trouble doesn't last always," which is from an old spiritual. There were people who screamed, literally screamed, screamed as an act of jubilation because that was an affirmation of the faith. Now a white preacher would have said, "Rest assured that ultimately in the eschaton, there will be the assurance that the resurrection will be affirmed." You know, I don't know what that does for somebody whose kid got ready to jump off the roof, or spit in their face, or someone who had a fight with his wife. The black church has always been able to identify with the idiom of the people; it's known its people pretty well, and has had to deal with the underside of its people. The white church has always come, not to hear that stuff, but to seek some religious sanction for what it was.

I do think there is a psychology of poverty and oppression that is pervasive and transcends racial barriers. There has always been a fairly good relationship between poor whites and poor blacks in the South, because they were thrown together. They all lived in the same kind of shanties; they had relationships, albeit covert, on all sorts of dynamic lines. There has always been an attempt on the part of those who were in power to keep those two groups from coming together, to pit them against one another. Wallace plays to a mentality that itself is powerless; its only claim to fame is whiteness, so there must be a tenacious holding on to that in order to say I am better than the only person I see under me, who is black.

III

I don't see any revolution that was sustained by mass movements. You get to the point where you have got to take advantage of the gains that have been made, and then implement them into a new system. It is much easier when you have a tangible goal to go after and you knock it down. But that is always a means to an end and not an end in and of itself. I am unapologetic about saying that we don't have anything to pull people into — King would not have had. In Memphis, he was trying to take on the economic power in this nation and say that poor folks have to be organized to get what they want. It is the same thing that Caesar Chavez said, and that is the reason Mrs. King supported him; she could see the farmworker's struggle as a follow-through on what her husband was doing in Memphis with the garbage strikers. But he would have had to change tactics.

The '70s are a time when we have to figure out the new Easter egg hunt. When you take kids on an Easter egg hunt, you hide all the eggs. The next Easter, the kids go back to the same spots, but if you're slick, you hide them in a different spot. Well, what this nation does is hide all the eggs, and you learn where they are, and then the next year they are somewhere else. That is what Nixon and Ford have done. OEO money has either been cut out or shifted to HEW. It's no longer Selma, it is Washington. Or it's the state capitol where they do three cuts on welfare recipients! It's any issue that pertains to old folks. That is the new Easter egg hunt. The eggs aren't on the Selma bridge anymore; they are just not there. You can go anywhere you want to in Selma. You can eat at any restaurant. That is irrelevant. That has nothing to do with poor folks who get cut off of medical assistance. That has nothing to do with welfare mothers who get cut.

The point is that you go and find the eggs this Easter, and then because history is dynamic, you have got to find out what the new scheme is. You know, they are going to shift it to maintain power, and the job of those folk who have a social conscience is to find out where they are and deal with it everytime it comes up. You know, we are out of Vietnam, so now it is Angola. We're out of Angola, so now it is Rhodesia. But it's the same thing, the exploitation of poor folks in the interests of those that have vested interests in multi-national corporations.

I see a high correlation between domestic and international problems, and I don't think America is ever going to be serious about helping poor folks as long as it is pouring any money into Angola. If we can cut the poverty program yet continue high military expenditures, when part of that money might be used in Angola or Rhodesia, that has a direct correlation to black folks. When Roy Innis tries to get black Vietnam veterans to go fight in Angola, that is no longer simply an international issue because I have black Vietnam veterans in this church who do not have work because they are a part of that eight-and-a-half million unemployed. So, that is a very critical, domestic, international issue. I say, "Hell no, you don't go over there and fight black folks. We will feed you first before you start destoying your own people.”

I wax warm on these things, because I think they are critical to what the black church is actually doing. If they can continue to subject workers in the Republic of South Africa to low wages, that means that black folks in this country are still in trouble, because those same corporations will refuse to hire people here as long as they can exploit people somewhere else. So, I have got to stop exploitation over there so that the man cannot run away and leave me starving here.

IV

I think the problem with the '60s was that people didn't face the fact, when you get involved with social change you have to deal with failure and death. That is what Kent State taught the white community. You see, white folks didn't believe when they saw the dogs and the hoses in Birmingham; but when they shot those kids at Kent State, that revealed a lot. They were then able to see that it was true what black folks were saying, that you cannot just stand up as if there is "freedom of speech" and say you do or do not believe something, because they will get you. They really will. Now, that's enough to throw people off and leave them disillusioned for a long time.

But the whole history of the black experience has been a history of having to deal daily with failure and death, so we didn't get that sure. We didn't have to go into transcendental meditation or anything like that. The very essence of the Christian experience had already incorporated that. See, we didn't have any psychiatrists to go to. We had to deal with death and failure and "I am not a man" and they will shoot you and burn down your house whenever they want. So, I think we could make the transition much more easily than those who had invested too much in the American dream.

White people have always been used to winning. We just don't have a good, practical theology of winning. That's the history of American imperialism. So, how do you deal with the fact that kids get shot at Kent State? That was a mind-blowing thing; that shook me.

When you look at the '60s, we paid the price. The two Kennedys and King are gone. The hope that we all had for this nation — and black people had that hope too when they looked at Kennedy — you really saw that you could get a good guy up there and they would kill him. Somebody would kill him. And that just says, what the hell, why should I care, why should I get involved? What's in it for me other than dying? And it's just better to survive.

Black folks have always known that when you can't eat steak, you eat fatback. Fatback might be working for a full employment bill; fatback might be pushing for national health insurance. Black folks have always been more practical in their politics.

So, I'm trying to pull some things together. This is a great church to be in. It gives me an opportunity to see if I can shape the ways some things are going. I'm excited about what could happen.

Tags

Bill Troy

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)