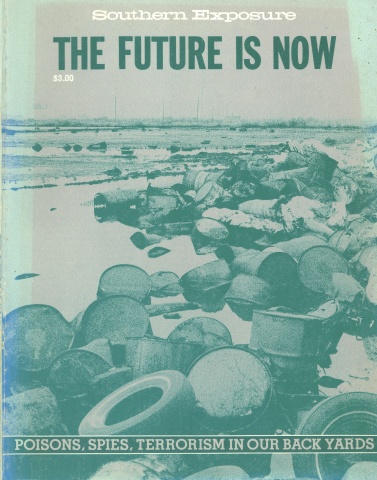

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

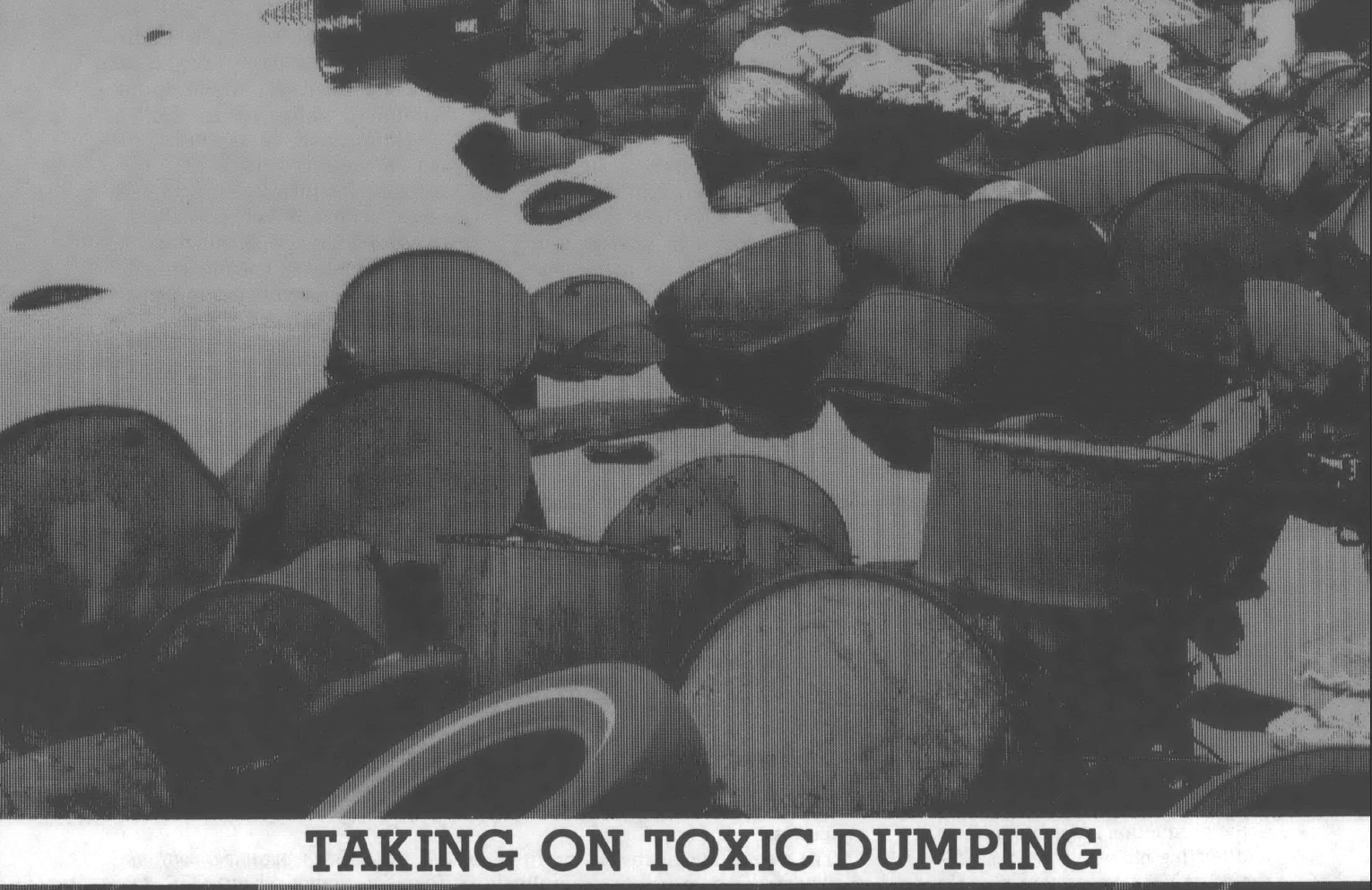

Love Canal. PCB dumping in North Carolina. PBB poisoning of livestock feed in Michigan. Kepone in the James River — all these events have made national headlines over the past few years as we have finally had to face the legacy of our lax approach to monitoring chemical wastes.

However, such nationally significant events are really only the tip of the iceberg. Every state in the South has been the scene of harrowing episodes caused by chemical waste disposal, and new ones come to light every day.

Most of the blame for these atrocities must fall on the corporations which produce these lethal wastes. An estimated 90 percent of our hazardous wastes have been disposed of illegally or improperly by companies mostly interested in saving a few dollars on disposal costs. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and state regulatory agencies are underbudgeted, understaffed and underskilled — and consequently unwilling and/or unable to take the vigorous action necessary to protect citizens from the horrors of chemical dumping. Under Reagan’s leadership, there is little hope that the performance of these agencies will improve.

The all-out drive for industrial expansion in the South further compromises government policies towards hazardous waste. For instance, while North Carolina Governor Jim Hunt launched a vigorous campaign to bring the microelectronics industry — and its chemical problems — to the state, he was also steering an improved but obviously flawed waste management act through the General Assembly. A comparison of Southern laws with those in states like New Jersey which have labored to overcome their legacy of chemical nightmares shows just how weak an approach the South has taken.

States have largely focused on only one tack for “solving” their waste problems: burying them in landfills and hoping they’ll go away. This approach also applies to low-level radioactive wastes, which are also viewed as a “crisis” problem by most state governments. The problem is that landfilled wastes will not stay buried forever: they will leak, will enter the water supply, will endanger the health of people living around the landfill. Even the most technically advanced landfills will eventually leak some chemicals; many of these substances remain deadly virtually forever. However, alternatives like recycling reusable materials, neutralizing the most deadly wastes or even curtailing their production are viewed skeptically by most industry and government officials because to do so would reportedly be too expensive. So state governments are pursuing landfill programs that only defer the payment of the high costs until the time when leakage from these new waste dumps creates a new generation of Love Canals.

At the same time, state and EPA officials have refused to acknowledge the hazards that past dumping and landfilling have created. As people discover an alarming incidence of skin rashes, breathing problems and other health disabilities and link these symptoms to nearby waste dumping, the “responsible” state agencies assure them that everything is safe, that there is no problem — until local residents create such a clamor that their horrors must be faced. And in many situations — Love Canal and Memphis, for example — the help they finally receive is woefully inadequate.

Viewing the government’s poor performance in protecting and assisting these citizens, residents of communities slated for new landfills have fought back with vigor, telling officials that they do not want landfills in their communities. Most such dumps have been targeted for rural and lowincome areas, where people generally have less political power, but still the communities have rallied together and often stopped states’ plans to saddle them with the region’s waste products. Citizens in Hickman County, Tennessee, and Heard County, Georgia, have recently fought off landfills, and people in other parts of the South are now engaged in similar struggles.

State officials and to some extent the media have often portrayed these dump opponents as selfish people who oppose dumps out of fear and ignorance; their thinking is portrayed as limited to: “Not in my backyard, you don’t.” However, newly aroused citizens often unite with the victims of past dumping to agitate for sane waste management policies throughout their state. For instance, Tennesseeans Against Chemical Hazards (TEACH) combines victims of past dumping with opponents of new landfills to seek compensation for victims and improved regulation of all forms of hazardous waste. In fact, TEACH is representative of a new wave of community organizing throughout the South aimed at revamping our approach to waste disposal and protecting us from present and future Love Canals.

To dramatize the seriousness of the hazardous waste dump dilemma and the vigor of citizens’ response to it, we have prepared this section as a brief reader on the problems the South is experiencing with both past dumping and new landfill plans. Kenny Thomas analyzes the frustrating attempt of Memphis residents to get relief from the city’s legacy of poorly regulated dumps and “midnight dumping.” Betty Brink shows how inept state regulations allowed a “temporary” low-level radioactive waste storage center in Texas to become a long-term lethal hazard. Ginny Thomas and Bill Brooks profile Georgia 2000’s successful campaign against a hazardous waste landfill in Heard County, Georgia. Finally, Nell Grantham discusses her own horrifying ordeal with an abandoned chemical dump but explains how this experience led her to help start TEACH.

Much of this material is extremely depressing; the exasperation Memphians feel as the city, state and EPA ignore their problems is gruesome to consider. However, throughout these articles the determination of the individuals involved is quite inspiring. As we learn from Nell Grantham, even those Memphians who got the cold shoulder from their government have stuck with the efforts of TEACH and tried to assist others facing similar problems. Therefore, despite the gloomy nature of the problem, the continued work of groups like Georgia 2000 and TEACH does point to some optimistic conclusions. As more and more individuals band together to protect themselves from hazardous wastes, they are laying the groundwork for greater grassroots involvement in combating our chemical hazards and protecting people from the tragedies that have occurred in the past.

At the end of the section, we have provided a brief glossary of the chemicals, and their potential effects, mentioned in these articles. Our thanks to the Highlander Center and its excellent publication, We Are Tired of Being Guinea Pigs!, for the information provided.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.