This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 2, "Long Journey Home: Folklife in the South." Find more from that issue here.

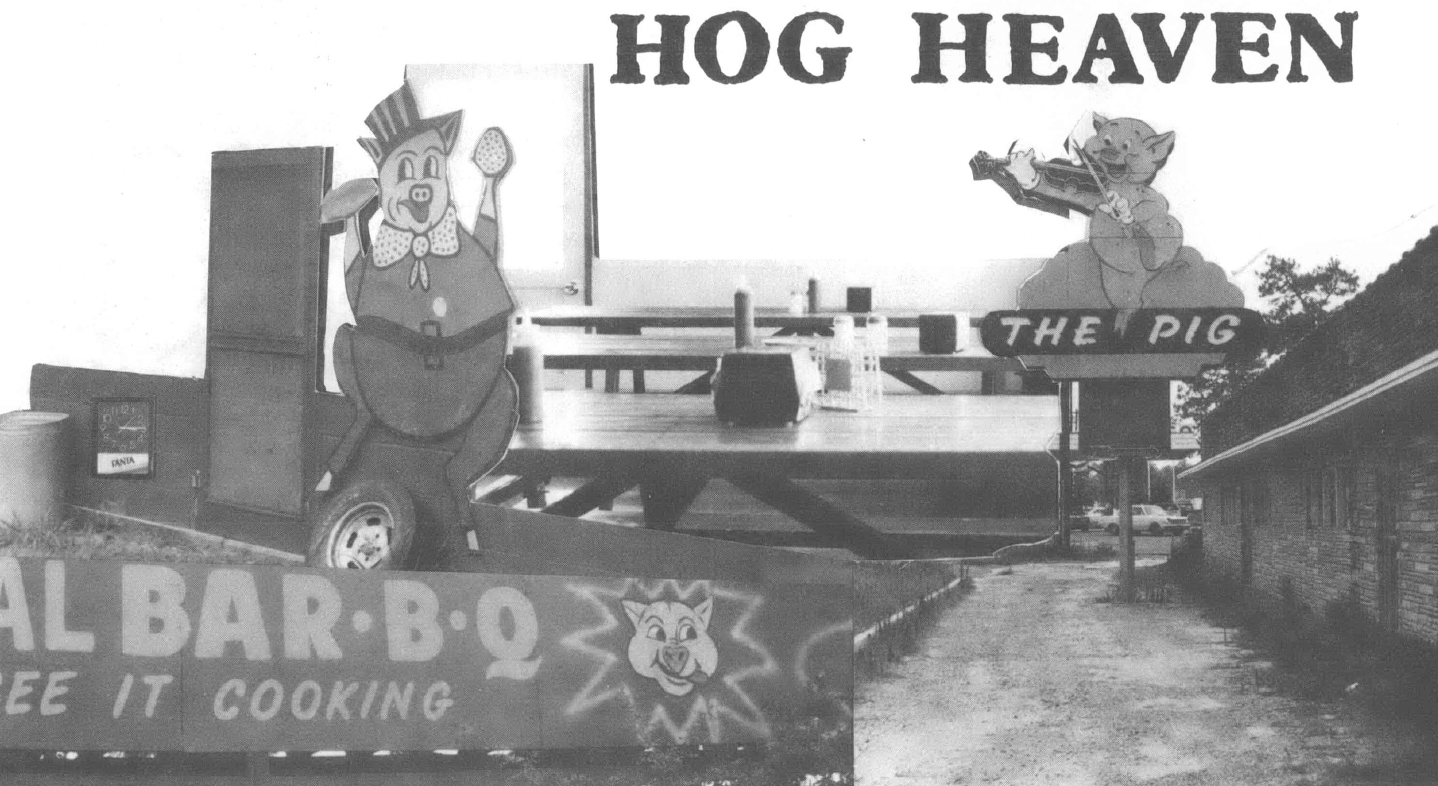

Fat signboard piggies run, dance and fiddle all along the highways of the Southeast. They point to neon wood-fires, urge you to "Watch It Cook!" and generally display gleeful enthusiasm for their own kind's sacrifice in the barbecue pit.

Restaurateurs would have you believe that Southern pigs, like people, take a lively interest in every detail of the preparation of this all-important dish. And Southern people, as anyone knows, take their barbecue very seriously. The ritual of barbecuing has endless variations from region to region, or even town to town. Yet in each locale, the resident experts will assure you that theirs is the only way, the only method yielding what is termed "true barbecue."

"People drive miles out of their way to eat here," brags Avant Taylor, long-time owner of Avant's Barbecue near Blackshear, Georgia. So saying, he serves up a sandwich of well-done sliced pork shoulder smothered in a hot gooey mayonnaise-based sauce.

Back in 1931, Avant paid a man in nearby Waycross $100 for the sauce recipe. He claims it makes anything, "even tossed salad," taste better.

But you probably couldn't pay another chef $100 to let that thick, pink stuff anywhere near his barbecue. Like Charlie Watson, manager of Wilber's Restaurant in Goldsboro, North Carolina, a purist: "You'll mess a pig up if you start putting all that stuff on it." The only thing Wilber's combines with the meat is hot sauce, made by adding red and black pepper to a pot of boiling vinegar. The result is a very mild, moist and smoky dish.

These are two extremes of merely one dispute in the controversy-filled world of barbecue. Like many matters of opinion, it is made more troublesome by a lack of facts. Somewhat like religious tenets, barbecue sauces are touted as essential while, at the same time, being declared unknowable. Cook's and pitmen are masters of evasion when you try to wheedle an actual recipe out of them (Charlie Watson notwithstanding). "Why I wouldn't even know how to tell you to start," claims one South Carolina cook of 27 years' experience. "I just throw it in a pot, a little of this and a little of that. . ."

"Oh, so the sauce comes out different each time?" the gullible customer may ask.

"No, no, no!" The idea is outrageous. "It tastes exactly the same every batch!"

So, it's a matter of faith in "old family recipes" never to be revealed. Though one suspects that the parallel with religion applies here as well: the age, hype and mystery surrounding the sauce must affect its taste quite as much as a cup more or less of vinegar.

Another point for hot argument: Must the whole hog be used or do Boston butts alone yield the quality of meat fitting for barbecue? Again the answers vary radically, even within a single state.

The walk-in cooler behind Wilber's is hung with 90-pounders split down the middle and missing only feet and guts. "When our hogs are cooked," explains manager Watson, "we bring them in to the chopping block and peel them like you would peel a potato. You need the whole hog to make barbecue right. People like it best with a little of the fat and crispy skin mixed in."

But barely into the North Carolina Piedmont, at Huey's in Burlington, they boast of just the opposite: shoulders alone are used, ensuring tender, moist and fat-free meat. "Our shoulders make the Rolls Royce of barbecue,” Paul Huey maintains. "Our prices may be a little higher, but you're getting what you paid for—pure, lean pork."

The type of wood burned to make coals or ashes for the pits is yet another item of contention. Throughout North Carolina and Virginia, it's a given that hickory-wood smoking is the only proper method, and most advertisements claim its use.

"But you just go out back and look at their woodpile," reveals a more honest businessman. "You'll see a lot of oak and very little hickory. . .hickory's expensive and hard to find nowdays. Hell, I have enough trouble just keeping up my supply of oak. Hardwood, it must be. But it'd take a mighty delicate set of tastebuds to tell the difference between oak and hickory."

Down in eastern Georgia, the latter is openly admitted to be out of the question. So here the issue becomes, what kind of oak? Gator oak with its thick skin-like bark is the favorite since, unlike water oak, it yields heavy coals just right for cooking.

But should coals be used, or do ashes cook best? What is the optimum roasting time? How large should the hogs be? How far the racks from the fire? Must the meat be basted during cooking or only after? Is sliced or chipped barbecue the best?

These and many other fine points are the subject of endless hours' discussion amongst connoisseurs of the dish. Yet what seems to be most important, finally, is who is doing the cooking, and where and why.

Bill Dunham, for example, attacks his job as pitman, caterer and chef unlike anyone has before or since. The result is a totally individual meal, to say nothing of the show which accompanies its preparation.

Dunham and his kitchen are not hard to locate, once you've found the tiny, near-tropical town of Kingsland, Georgia, just four miles north of the Florida line. "You go up town, and you ask anybody, 'Where can I find Bill's Barbecue?' and they'll tell you," the massive black man accurately claims.

"We have a-a-all the dignitaries come down here — bankers, and doctors and lawyers, yes sir! Sometimes I don't have nothing but bankers!"

"Down here" is a small signless pit - kitchen - dining room - storefront combination, somewhat shakily constructed by Dunham himself. It is squeezed in between his son's barber shop on one side and an abundant garden on the other. Bill's brick-patterned, tarpaper-covered home is next door, and flowering plants and trees fill what little space is left.

The chef was taking the day off from barbecuing. "It's just too hot, and I've gotta help Mama here put up all these vegetables." However, he is always willing to lecture on his art, which he proceeded to do from a front porch armchair surrounded by pans of purple hulls and okra.

"When I first started off barbecuing 47 years ago, it was to throw a party for my timber crew, to give them a big blow-out, don't you know. We did that maybe once every three months; there was 77 of them, and I couldn't afford to carry them to no restaurant. So we'd buy a hog, and cook it here, the way the old Indian peoples did way back yonder. And then I kept going, kept going, until feeding became my business."

The Indian method consisted of burning a large log — live oak or water oak or hickory (but no black gum or pine!) on a grate until the coals fell through. These were shoveled into a deep hole in the ground, and the hog, which had been quartered, was laid on a rack above to cook.

"But if there come a rain during that time, you're in trouble, don't you see. So then for a while we used a tent."

Nowadays, Dunham has the pit inside for convenience's sake, but still practices the Indian method upon request. It makes a colorful display at the many cookouts he caters for businessmen and politicians at resorts from Georgia's Golden Isles to the Florida Gulf Coast.

Mixing with the "dignitaries" and directing huge cooking operations are two of the greatest pleasures of Bill Dunham's work. He proudly tells of one event he catered for the St. Regis Paper Company of Jacksonville, where 5,000 people attended. "There were nine Greyhound buses, escorted by the Florida road patrol to the Florida line, then the Georgia road patrol took 'em on in to the party." Other enormous dinners have been prepared for the Georgia Bulldogs and friends, gubernatorial candidates and their allies, college deans, rich cattlemen's sons, and the Florida State Rangers. Barbecue Bill's fame has spread.

"I was sitting down at one party, talking to this man, and somebody across the room called me Bill. Well, I didn't know this fellow I was sitting with from Adam's house cat, but he says 'Are you Bill Dunham?' I says yes. ‘Well’ he says, 'they were talking about you up in Tennessee the other night!' "

Newspaper clippings and letters from the executive secretaries of pleased patrons illustrate the stories. In well-worn photos, we see Bill, magnificent in chef's white hat and apron, face shining with sweat and pleasure, while four or five assistants (including his wife Charity and various relatives) serve mountains of food to tuxedoed and bejeweled party-goers.

Dignitaries aren't the only ones who appreciate Bill's barbecue, however. Neighbors, friends, and relatives crowd the tiny Kingsland restaurant every weekend, picking up take-home orders, eating a plate there, or just sharing talk and a bottle with Bill in the back room. "I can't run them out of there," he complains contentedly.

Of course, he will not reveal anything about the recipe for his famous sauce. But, Dunham is willing to share some important secrets of barbecuing the meat:

With the help of a neighbor boy, a fire is started in the pit (really just a big brick fireplace right in the kitchen, with horizontal bars for the meat and a sheet metal cover to be leaned up against the opening during use). After three or four hours the wood has "burnt down good" to form coals, and a few cardboard boxes are thrown on to make a final blaze, cleansing the metal racks above.

Then it's time to lay on the hog, cut in quarters, meat side down. (This is a special trick of the trade, Bill lets it be known. There's no danger in telling it, though, since it takes more than mere knowledge to make a barbecue chef: "I can do it and it works, but the other fellow tries it, and he fails!") The temperature at the racks (positioned four feet—rather than the normal two-plus — above the coals) is 250 to 300 degrees, and the meat is left there for 40 minutes. Then, it's turned rib side down to continue cooking for six to eight hours depending on the thickness of the piece.

Most barbecue pits are separate from the restaurant, and are so hot and smoke-filled that pitmen are forced to watch the process through pyrex windows, or to wear goggles and masks on their quick dives into the cookhouse. But Bill Dunham watches the whole thing from the comfort of an overstuffed chair, with a radio and electric fan handily nearby.

The difference is made by his "cool" fire: the dripping of the grease onto the coals makes just enough smoke to flavor and cook the meat, but not enough heat to burn the pork and drive the chef away.

"If I gets too much fire in there, I've got me a bucket of water and I just go to fighting it. And then I sit right back down and watch it cook."

Burning the meat, or scorching it by basting with sauce during cooking are two of Bill's major complaints about his competitors. Another sin is using too heavy a sauce. "Some people put a-a-all that crap in it," he waves a hand in disgust, continuing in a language as distinctive as his cooking. "But if you do that, you ain't gonna be able to taste the meat! You gotta use your monocklins with cooking!"

Often served in conjunction with Dunham's barbecue is another favorite, "a thing they call The Brunswick Stew."

"Don't many people know how to make that. I mean, all kinds a people try to do it, but it's gotta be just right. . . " At this point he draws a yellowed and spattered piece of paper from a back pocket, and unfolds it gently along weakening seams. It has the appearance of many little worn blocks of paper, held together by threads, and reads: 15 lbs. beef 15 lbs. pork 9 lbs. chicken 12 cans butter beans 12 cans tomatoes 12 cans sweet peas 12 cans corn 15 lbs. potatoes 4 lbs. onions 4 bell peppers 1 stalk celery 1 box salt 2 gals, catsup 2 lbs. butter 3 bottles Worcestershire sauce 6 bottles A-1 sauce 1 bottle hot sauce 1 gal. tomato juice 1 can black pepper 1 gallon mustard 1 gallon V-8 juice 1 pkg. garlic season 1 whole garlic

"Course, this is just my shopping list," cautions the cook. "I say, 'one can black pepper' but that don't mean put the whole thing in there. You can't buy a part of a can, so I leaves it up to you to figure out what's right."

Do hushpuppies and slaw go along with it? Bill is amused by the idea. "Hushpuppies is for catfish," he explains patiently. "I give the people what they want — light bread or rolls, mashed potatoes, baked beans, or potato salad."

Despite his age, 76, and the fact that "the Health Department hounds me some," Mr. Dunham shows no signs of slowing down.

"I make a good living." He nods meaningfully toward the nearly new pickup which carries him and his feast to and from catering jobs and pig pickings. "I've had three restaurants hereabouts offer me a job as pitman, but I turned 'em down. They wanted to give me less than $25 a week."

Bill plans to pass his business on to his children, when he gets old and tired enough. But for now, he's too busy enjoying himself while feeding the dignitaries.

The clientele is strictly working class at Avant's in Blackshear, Georgia. Not far from Bill Dunham's home, the scene and science of barbecue here might as well be a thousand miles removed.

At 10:30 am, construction workers pull their trucks into the dirt parking lot beside the small roadhouse-restaurant on the Savannah-to-Waycross highway, for a morning sandwich and beer break. The pine paneling, bar stools and mirrors make it clear that — though the establishment's been serving barbecue for 44 years — liquor is still its main reason for being.

"We were a package store about nine years before we started making sandwiches,” says long-time owner Avant Prentice Taylor, or "The Doctor," as he's jokingly called. "In fact, we were one of the first to be licensed when Prohibition was repealed and Georgia voted wet."

But the place has gone through many changes since then. "First, we had groceries on all those shelves; we always had gas, and curb service. As the fella says, 'rag rugs, wash tubs, sewing machines, needles, and whatnot' — a general store."

The package store still adjoins, and there are living quarters and a kitchen in the back. "Many's the time somebody would come in and order a sandwich, and we'd have to get up from the dinner table to serve it. And the chicken'd get cold and the grits'd get lumpy, but that was the business."

Taylor's wife, mother and daughter have all worked here, too, at one time or another, but the family has long since moved out to a nice house down the road.

One can only imagine what Bill Dunham would say about Avant's claim to "the best barbecue in Georgia." The hamburger-bunned sandwiches, wrapped in paper "to go,” are heavily laden with a thick, hot, pink sauce. A bag of potato chips and two pickles complete the serving.

During tobacco season, especially, Avant's does a booming business in barbecue sandwiches (the only form of the dish they bother with). For once, everyone has plenty of money; people bring guitars and banjos and there's music and dancing 'til four in the morning.

An occasional tourist, strayed from Highway 121 up from Florida, finds his way to the roadhouse, samples a sandwich, and then drives on. "The word has spread — people come here from hundreds of miles around, just to buy our sauce by the gallon."

Avant's does their own barbecuing, too, in a small outside pit next to the restaurant, but it's their sauce which is distinctive and responsible for their fame.

Local specialties like this ensure that barbecue will never successfully become incorporated into a large fast-food chain. (There have been some attempts, but progress is slow.) "Everybody's got their own idea about what barbecue should be," explains one student of the dish. "Usually you'll find that what a person grew up eating, that's the taste he insists is the real thing."

Accompanying foods also vary greatly from place to place. From North Carolina's formulaic slaw, hushpuppies and Brunswick stew, the fare in coastal South Carolina has become slaw, light bread and barbecue hash on rice.

The hash, as concocted by D&H Barbecue of Manning, South Carolina, is made of meat from hogs' heads and other non-choice parts. These are placed in a big pot, cooked down thoroughly, and then mixed with a little barbecue. "A lot of other things" (catsup, pepper, hot sauce, to name a few) are added finally, and the whole batch is simmered a while longer. It's a filling, cheap meal at $1.00 a pint, plus rice.

D&H has a small, barren cinderblock dining room with picnic tables and benches for the customers. The walls are decorated with drug-abuse posters and hand-written signs thanking people for cleaning up their own mess. Orders are given directly to the kitchen hands, through a window at the back of the room. But the main business here is take-out. From another window, also connecting with the kitchen, local people pick up barbecue and hash by the pound, half-hog skins for crisping at home in the oven, lard, cracklings and pig feet.

Here, as in many barbecue houses in the Carolinas, liquor in any form is strictly prohibited. The attitude goes beyond the region's normal Protestant-inspired disapproval of alcoholic beverages. It's a matter of principle, with complete loyalty to barbecue being required of the diner. If a man's interested in drinking, he's not going to be paying attention to the food, is the general belief. "Liquor and barbecue don't mix," D & H's owner, John Denny, puts it simply.

D & H is open only Wednesday through Saturday. Employees include "one colored man" (who watches the pits), "one boy" (who cleans up) "and two women" (who wait on customers).

Such utilitarian decor and frank hog orientation contrast sharply with some of the more upwardly mobile barbecue establishments in North Carolina.

At Huey's in Burlington, for example, hanging plants and stained glass screens reflect owner Paul Huey's belief that "eating out is a form of entertainment, these days. People want an escape and we try to provide it with our nostalgia bit."

Thus, the 31-item salad bar is mounted on an antique tobacco sled, and the elegant art-deco menu contains cute, self-conscious phrases about "Eastern Carolina Hawgs."

Huey (who majored in history in college) takes a genuine interest in "our Southern ethnic food." Fifteen hundred pounds of pork shoulder are barbecued under his direction here each week, and its flavor is rightly renowned. Yet somehow the pig seems very far away.

A lot of things have changed in barbecue lately. While the dish itself seems more popular than ever, Health Department regulations and the scarcity of hardwood have altered many of the traditional approaches to cooking and marketing. Most troublesome is the difficulty in finding men willing to perform the hot, strenuous and lonely work of running the pits all night. Pitmen are usually older blacks, who often tend farms in addition to their restaurant jobs. More and more restaurateurs are turning to gas or electric heat as a way out of the labor predicament. Besides being less trouble, it is a faster and cheaper method.

Others, thank the Lord, have their principles.

"People say you can't tell the difference," one manager of 15 years sniffs indignantly. "But I tell you, it's like night and day... If we have to give up pit-cooking, we'll close. That's all there is to it.

Tags

Kathleen Zobel

Kathleen Zobel grew up in Apex, North Carolina, and is currently a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies and co-editor of its weekly syndicated column, Facing South. (1977)