This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

"Great art is not an expression of Personality but an escape from it. Of course, only someone with a strong personality can know what it means to want to escape it." -T. S. Eliot

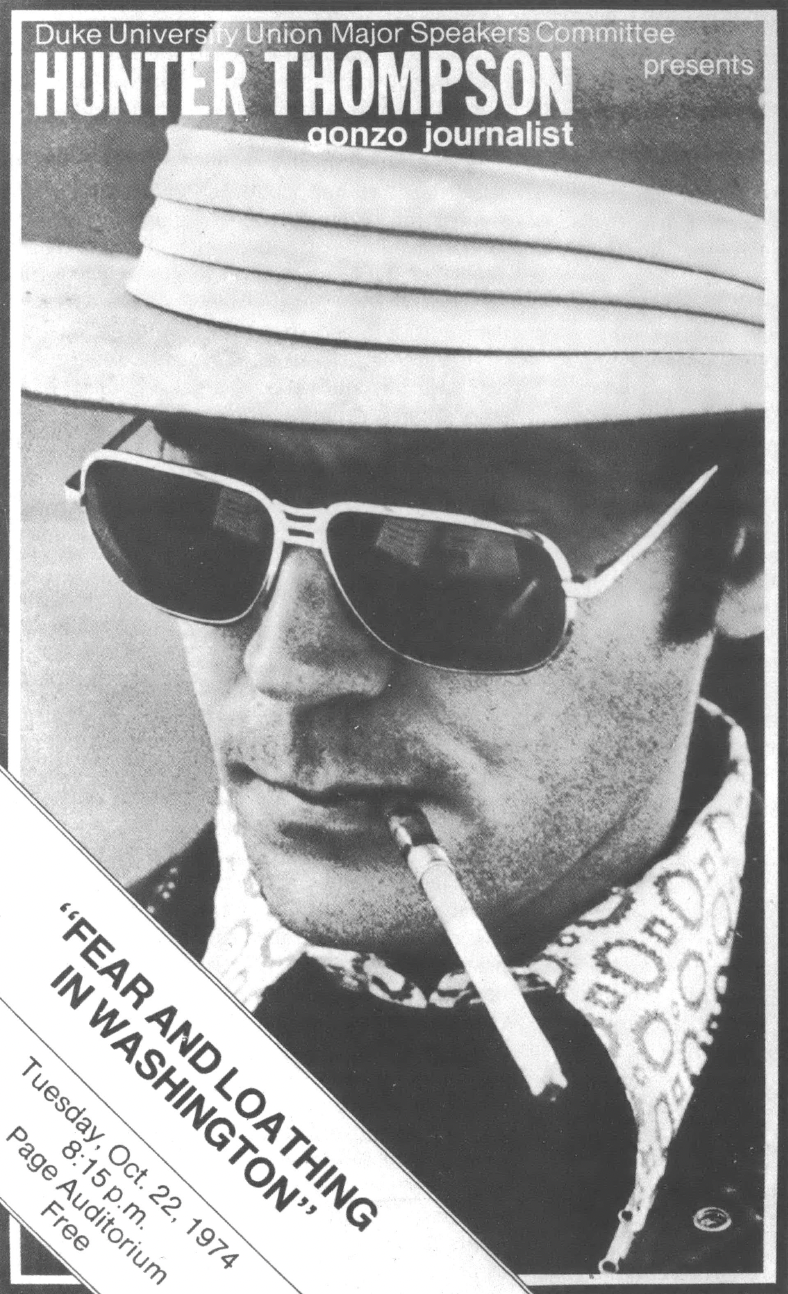

The audience that had assembled at Duke University's Page Auditorium on a cool October evening could have been mistaken for any crowd gathered for a rock concert. Frisbees and paper airplanes flew from the floor to the balcony and back again. Joints and bottles passed down the rows of seats filled with long-haired students. But there was a strange difference. Instead of banks of amplifiers, the stage contained only a podium, a few chairs, and a microphone. Instead of programs or complimentary t-shirts, spiral notebooks were eagerly clutched in young hands. The attraction that had drawn these Duke students, the self-conscious cream of Southern academia, was not a band but a single journalist, a writer who had emerged from the poorly-paid drudgery of free-lancing into the limelight of popular and professional acclaim. The Big Draw tonight was Hunter S. Thompson, "The Dean," as the posters had announced, "of Gonzo journalism."

I.

Thompson, an ex-Kentuckian, had written for Sports Illustrated, The Nation, and various newspapers before attracting popular notice with one of the earliest forays into New Journalism, a book on California motorcycle gangs called Hell's Angels. He followed with several articles for Rolling Stone and a frenzied campaign for sheriff of Aspen, Colorado, on the Freak Power ticket. Perhaps his greatest achievement to date, however, has been Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a semifictional account of a week long, drug-induced, credit card powered attack made by Thompson (under the alias of Raoul Duke) and Chicano activist Oscar Zeta Acosta (passing as a Samoan attorney) on the hype-ridden Nevada way of life.

Fear and Loathing is an LSD fancier's version of the Divine Comedy, a journey through a uniquely-American Purgatory with eyes forced wide-open by chemicals. When it first appeared, serialized in Rolling Stone, it rang bells of recognition in the heads of activist-visionaries who had tried to maintain the spirit of the sixties in the face of the deadening Nixon seventies through sheer audacity and adrenalin. It was a book of great perception, compassion, and humor, and it earned Thompson the National Affairs desk at Rolling Stone, a job that basically entailed covering the 1972 Presidential primaries.

As Timothy Crouse recounts in his book on the media's campaign coverage, The Boys On the Bus, Thompson hit the Ziegler-cowed press corps like an obscene thunderbolt, disregarding all the cherished rules of political journalism, such as "privileged information" and "objective reporting." He despised Nixon and made no effort to hide the fact. He had a qualified, tentative regard for George McGovern though, and was one of the very first journalists to understand the strategy of his campaign and take it seriously. Upon publication of his collected campaign articles, entitled Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, Thompson hit the peak of his profession. His articles were sought after, he was interviewed by Playboy, and Garry Trudeau created a new Doonesbury cartoon character named "Duke."

Thompson's meteoric rise as an “articulate freak” coincided exactly with the re-emergence of the Reporter as pop hero; but while journalists like Woodward and Bernstein were relatively normal folk, soft-spoken, and essentially linked with the system and structures they "constructively criticized,” Thompson was something else again. Battered, defiant, and determined to stay high, he is the logical successor to the short-lived heroes of the late sixties. Hunter Thompson has become, probably without his knowledge, and almost certainly without his consent, a Star.

II.

All this became disturbingly apparent as the Duke crowd, annoyed that Thompson was nearly an hour late, stomped their feet and clapped their hands in unison. All that was lacking was the occasional strident yell of "Boogie!" or "Start the music!" This crowd had not come to be lectured, but to be titillated. And at first they were not disappointed.

Thompson shambled on stage with the student M.C. anxiously guiding him to the lectern. As he was introduced, Thompson grimaced and squinted out at the audience. A tall, nearly bald, powerful looking man, he could easily have been mistaken for the sort of mean Army lifer who makes his career in the Airborne divisions. Only his cigarette holder implied that his personality might belie the visual impression.

"I'm pleased to be here at Richard Nixon's alma mater," he began, referring to Duke's Law School. There was only scattered applause. Re-opening an old wound was not guaranteed to appeal to proud Dukies. "First, I really don't know why I'm here. I don't have anything to say. I was on my way to Africa when the agency that ships me around like a piece of meat told me to come here. I don't even know if you paid anything to get in, but at any rate, all I'm going to do is to stand up here and argue."

And that was precisely what happened. Thompson leafed through a pile of notecards bearing questions submitted by the audience, flipping them one by one onto the floor where they joined a dozen or so paper airplanes that already littered the stage. Occasionally he would mutter "bullshit," or "Jesus Christ," all the while shaking his head in disbelief. He paused when he reached one card, took the time to re-read it, then leaned into the microphone and said, "This one wants to know, 'What's the happiest you've been in the past month?' Christ, isn't there anybody here with any intelligence?"

The question was resoundingly answered in the negative by a barrage of stupid queries shouted from the audience.

"What's your favorite drug?"

"I don't do drugs."

"What do you think of Rockefeller?"

"Come on, get serious!"

"Does Nixon have a political future?"

"He'll try."

"What about Terry Sanford?"

"God, I hope not."

Things went on like that for a few minutes, the audience asking about motorcycles, the relevance of voting, the sex life of Hell's Angels women, and various minutiae that had become attached to the Gonzo legend. Then came a voice from the balcony:

"What are you high on right now?"

This question, nightmarishly reminiscent of the Joplin and Hendrix concerts, where the prime topic of conversation was whether the star was tripping, on downs, or drunk, seemed to catch Thompson like a blow to the solar plexus. He had previously been sparring, but his mood suddenly changed. He turned on whom he obviously considered his tormenters with nearly incoherent relish. The fact that he probably was high at the time did not do anything to calm him down.

"What the hell do you fucking people think you're doing? . . . You're the wave of the future, God forbid. You're the type that went to see Evel Knievel bash his brains in at the Snake River Canyon . . . You're beer hippies! You don't give a shit or lift a finger to change things." Now anyone at all familiar with southern academic life knows to be a Duke student is to be as close as one can come in this life to Perfection, at least in the eyes of Duke students. So Thompson's assault came as somewhat of a surprise. Brooding resentment grew into outright cat-calls and insults.

Thompson responded to this by wandering from one end of the stage to the other; mumbling, pausing to answer inane questions, or challenge hecklers to fight. No one accepted. Only occasioally did he remember to speak into the microphone, and then he generally answered a question nobody had heard. It was obvious that Thompson considered himself involved in a verbal barroom brawl. Yet several times he dropped the fighter's role to deal with serious queries. One student asked, "Who was the greater man, Neal Cassidy or Eugene McCarthy?"

Thompson immediately answered, "Cassidy. And thank you, that was an intelligent question."

A student asked if it wasn't possible to "infiltrate the system." Thompson laughed nastily and asked how the kid proposed to do this. When the student answered that he was a journalism major and wanted to air his ideas discreetly through a major newspaper, he was scornfully asked what ideas he had. There was a pause and then the quiet answer, "Socialism." With long years of newspaper work behind him, Thompson snorted in amazement at such naivete. But the wave of laughter the kid's brave vocalization had brought forth caught Thompson short. After all, here was one beer hippie with the guts actually to defend his commitment in a hall full of half-baked cynics. He leaned over the podium and advised the kid to go ahead and try it; there were a few editors into that sort of thing. It may not have been a realistic thing to say, but it was a satisfying bit of professional and political solidarity. There were few such human moments that night.

The unequal contest continued for a few more minutes, until Thompson flew into a fit at some particularly noxious question and threw his notes, water glass, and everything else handy at the stage curtain and began to pound on the microphone. At this point, the student committee responsible for the whole disastrous evening dispatched a petite, young woman to fetch Thompson from the stage. He was led off as sheepishly as he was led on, to a chorus of boos. Some were meant for the committee; most were intended for Thompson.

Afterwards, a small crowd of Thompson fans engaged the student committee outside the stage door in one of those interminable debates on Free Speech that are an indispensable feature of college politics. Thompson himself eventually emerged from backstage and wandered about the campus, talking to groups of students in a strained, though civil, manner. The next day, he would be off to cover the Ali-Foreman bout, no doubt glad to be away from Durham and dealing with a fight in which, with any luck, he would not be a participant.

III.

For those he left behind, however, the whole bizarre incident raised some disturbing questions. In the first place, some of the audience that night had not been punks; there were many people there who had gone through the same changes and ordeals as Thompson. And like him, they were attempting to lead committed, humane lives in a society that frowns on that sort of thing. In their daily hassles, Thompson's work had been a welcome assistance. It was painful to see him becoming a prisoner of his image. Finally, there is always the nightmare memory of Hemingway and Dylan Thomas, leading lives that were caricatures of their dreams. The comparison becomes more explicit and deadly when it is realized that Thompson's true predecessors, as mentioned before, were the sad, doomed geniuses of sixties rock music.

There are enough tragedies in this benighted decade to keep us busy: the loss of a valuable writer and man is not at all necessary. All we can do though, is wish him well as he battles the Great American Success Machine, an enemy as corrupt as the Hell's Angels, as elusive as an LSD vision.

Tags

Steve Cummings

Steve Cummings, a native of Florida, is a cultural historian and a member of the staff of the Institute of Southern Studies. A former organizer of migrant farm workers in Florida, Mr. Cummings now lives in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he handles promotional chores for Southern Exposure. (1974)