This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

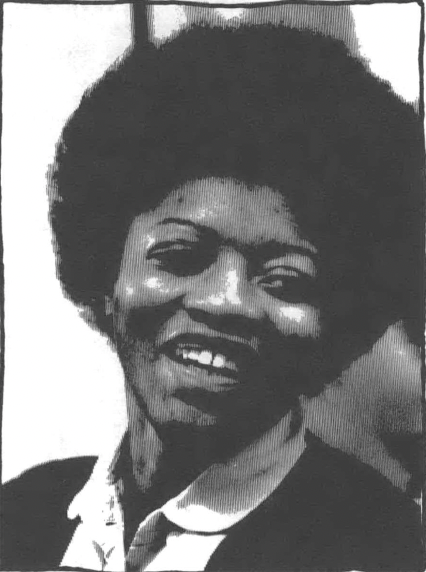

During the trial of Joan Little, I was teaching at Attica prison in New York State, but word about her and her acquittal was often discussed in my classes there. She was the heroine to the North Carolina inmates; a black woman from down home, down South, making a strong stand.

Later, I began teaching acting and creative writing at the NC Correctional Center for Women in Raleigh, and it was here that I met Joan. Seeing her for the first time, I was amazed - she seemed so small and skinny and young to have made the fight she did.

Joan was a member of my part-time acting workshop and later joined “Souls from Within,” a full-time project for the women. She was frequently disturbed by articles and plays that were written about her. “That ain’t me, ’’she would say. And I would encourage her to write her own story, for I believed there were many people who would like a firsthand word from the real woman.

Joan offered to tell me her stories on tape, if I would edit and organize the material. I agreed and we started the tapings in August of 1976. — Rebecca Ranson

I Am Joan

I was born May 8, 1954, in Washington, North Carolina.

I got six brothers and two sisters. I’m the oldest in the family. I am an average, twenty-two-year-old woman trying to live her life. I know that now under the circumstances that I’ve undergone that it’s very important that I not go back to the old way of life.

You know, life is one hole. It’s like being on a playground; you don’t learn how to play the game, you got to get off on the side. Life is not gonna stop for you. It’s gonna continue and go around and around....People expect a lot out of you. People try to stereotype you as a person. I am a human being; one that breathes, hears and sees the same as anyone else. I am not what someone has picked up out of a fairy tale, something that came out of the seventeenth century.

I am not against the experience that I’ve had in life or the things that I’ve done. I think that what I’ve done, where I’ve been, what I’ve been through have all taught me and have been a major factor in my finding out who the real Joan really is. Because two years ago I didn’t know who I was and what I wanted my life to be like. My life at that point was only going up to the poolroom with my friends; going out every now and then. Now I don’t consider myself as being the worst sinner in the world, and I definitely don’t put myself in the category to say that 1 was a saint. By all means no. 1 was far, far away from being a saint, but I never considered myself as being the type of person that did all the really bad things.

My past is past to me. It’s like a distant nightmare that I don’t want to relive ever again. I am a new Joan Little. At one point, I looked at myself as being almost a tramp on the street, someone that had no future or no meaning in life. If I were to pass away, I would of felt like I was just another corpse that was making room for somebody else that was coming into the world that could do something meaningful. Now, I see that regardless of what you are or who you are or what you might be...even a wino in the street has a purpose. That person who stands out in the street corner has a reason for standing out in the street corner.

Basically, I think this society has come to the point wherein they are too hard, too harsh and definitely too judgmental against their own kind. They’ve stopped looking into what they’re doing and looking into somebody else’s backyard. Besides I can’t even begin to look in somebody else’s backyard because I haven’t raked up my own. You know, my own experiences have taught me a lot, and I feel that at twenty-two years old, I have matured enough to say that my experiences have been those of a woman in her forties.

Teaching

I was born in a house on Greenville Road, and then Mother moved to 418 Pierce Street and that’s where I grew up at. It was like two houses, one house, but both of them was joined together and like you could just step right across from one porch on to the next porch and go on. Then we moved out to the country and behind it we had this wood house, a house where you keep wood in and all kinds of stuff. My mother had an upholstery machine where she had learned how to upholster sofas and stuff and she had all her old trunks from way back. It was real nice in there. She had all her clothes, coats and stuff out there.

I went out there when I was out for a school break during the summer, and cleaned all that stuff and made it neat. She had a dresser that looked like a desk, and I took all the chairs and set them up in there and made a school. I used to go downtown and buy paper and pencils and my brothers and sisters had nothing to do, you know, cause I had to clean up the house. After I finished cleaning about twelve o’clock I’d call all of them in there, and I’d give them something to do and show them how to write and make letters. I’d put a letter up there and have them make the same letter I’d made, and I might put a straight line and say, “Make a straight line first and then come around and do this right here and you’ll have an H.”

I used to have a good time teaching school, but what made me mess up was, I started teaching my brothers and sisters about sex. Ha ha ha ha!! I was, I’d say about fifteen, and I was trying to find a way of doing things to keep my mind occupied so I wouldn’t have to start running the streets or whatever, you know, cause me and my stepfather wasn’t getting along. So this was my way of expressing myself, doing something that I really wanted to do. With my little sister, I’d get a piece of paper and say, “This is something that all little girls have, the vagina.” And I’d tell my brothers, “Now, you are different than her cause you are a male and you have a penis.”

Well, when mother found out she said, “oh, no,” and said, “No more, no more. You can go out there and you can teach them how to write letters but don’t show none of that.” And I said, “Well, if I don’t tell them, they gonna grow up and ain’t gonna find out nothing.” I’d tell my sister. She would have never known about her period unless I had told her. My mother always thought that you just don’t tell. She grew up in the old fashion.

Fathers

My stepfather lives at home. My real father lives in New York. My real father never lived with us, and my mother got married when I was six years old. I remember it very well. I didn’t accept the fact of her getting married and I think that my mother — she had some kids already — I think she should have considered the fact of the kids. She may have thought we didn’t know what was going on but we did. I resented that for a long time. I thought, “You ain’t my father and you can’t tell me what to do.”

Those kind of changes put Mama in the middle and that’s one reason why I started running out like I did. I could not deal with him, and he didn’t have the authority to tell me what to do. And he would tell Mama, “Joan is disrespectful. It’s cause you let her get away with it.” My mother never really put her feet down and beat me, but she was constantly aware of the trouble. Like if I said I wanted something, my father gave it to me and he wouldn’t even give the other kids things. He wanted me to come to New York and live with him, but my mother didn’t want any of us to be separated. My father left when I was eighteen months old. See my father was married already when my mother started dating him.

Let me tell you about my mother though. My mother never has been the type to run around. The first time my mother ever went to a club was when she went in one with me and that was last year. I went in to thank this man for giving me some money for the defense fund and she didn’t even want to go in there then. She ain’t never drunk no beer. She ain’t never smoked no reefer. Ain’t never shot no dope, and I said, “You ain’t never done nothing.” You know, I can remember her having boyfriends and stuff, but there was only about two of them, and I didn’t know them that well-then because I was small, but I knew them after I got grown because I remembered the faces.

Jimmy

Let me tell you what I ended up doing one time. I got so many weird things that happened in my lifetime. See my family is really big. In Washington there’s not that many Littles but my mother is really from Pitt County.

I didn’t know that the Midgets were any relation to me at all cause my mother kept us home all the time. We didn’t never go visiting anybody, so when they started living on our street, Mama told us Yvette was supposed to be a relation to us but that was as far as it goes. Kids don’t be listening to nothing like that. Far as I was concerned, we was just playmates and I used to love to go to Yvette’s house all the time cause she had a lot of brothers — Ernest, Lee, Jerry, Johnny — and they used to live two houses away. Ernest and all of them had a band and they used to get out there on the porch and play music and stuff. We’d get out there and be dancing, going in and out the kitchen and her Mama’d be in the living room with the door closed, watching TV. The band would be playing and we’d be running and she’d have kool-aid and dessert back there to eat. Oh, we’d be having a ball!!

I hadn’t ever seen Jimmy before — never in my whole life had I seen him. It’s so funny now. Jimmy was in, I think it was the tenth grade and I was in the seventh. There was an old truck parked there in the back of their house, a black truck. We was back there playing Mama and Daddy. Jimmy was supposed to be my husband. Yvette had my brother for her husband. Okay, we’d leave and come to Yvette’s house and eat dinner. Well, it was mud actually and then me and Jimmy would go home. Our home was on the other side of the truck and so we’d go on the other side of the truck and we’d be talking, you know. You know how you feel when you’re real shy cause you ain’t never been around no boy before and see, Jimmy was older. He kept telling me, “I like you.” And so I’d say, “I guess it’s about time for us to go and be eating and visiting Yvette again.” Then it started getting dark. They had a light in the back of their house. You could go down to the electric company and get them to put up a post light right in the back of your house.

Okay there was one of those back there and Yvette said she was going home. Jimmy stayed.

He and I were just sitting back there in the backyard talking and it was dark and there were honeysuckle vines growing all up on the fence and stuff. We had a place called “the woods” where we had made a path and we’d say, “Don’t nobody know how to go through the woods.” Me and Jimmy was sitting out there talking and...uhh...then he kissed me. That was the first time anybody ever kissed me before!! I said, “Well, I think it’s time for us to go,” and he said, “Well, okay.”

I think it was about the next week before I saw Jimmy cause he was in school and stayed with his grandmother around the corner on Fifth Street, and so he didn’t ever come around unless he came in the evenings to visit his Mom.

I was coming out and I saw Jimmy coming up. I said, “Hey, Jimmy, how you doing?” And he said, “Hey, where you going?” I said, “I’m going to the store,” and he said, “You want me to walk you to the store?” I said, “Yeah.” I was going to this store called “Shorty’s.” Shorty used to give me candy, snowballs, cookies and stuff. He knew all of us cause we had grown up around Shorty and you know we got used to seeing him ride by on his bicycle. He was a real short, fat man. There was this warehouse right across the street from us and it’s dark, not real dark. Jimmy walked me to Shorty’s just about four or five houses away and then he asked me to go with him. When he asked me, I said, “Yeah.”

He started coming over to my house all the time. Like he used to say he was coming over to see my brother, but I used to play with my brothers all the time so my mother didn’t think nothing about it. Sometimes my brothers wouldn’t be home, and Jimmy’d come over and we’d be out there playing, riding bicycles.

He started to come almost every evening and my mother got on me. She said, “That boy is hanging over here too much and you’re hanging round that boy too much and I’m gonna tell him that he can’t be coming here to see you. He can come over here to see Jerome, but he’s a boy and you are a girl and you can’t be playing with him.” She went and told Jimmy’s mother not to let Jimmy come over there to see me. After that he kind of slacked up and left. I think I went to New Jersey and when I came back from there, I was about 17 or 18 years old and still liking Jimmy. I knew then he was my cousin, but it didn’t really phase me until I started getting up and I said now he’s actually my cousin, you know. Then, when I look back we wasn’t really doing anything. It was just, you know, alike. If I had been older and didn’t know he was my cousin we would have probably got into something but I was so young. I didn’t even know what a man was all about much less what a man could do to a woman.

Johnny

I used to tell my mother don’t try to hold so much grip on me cause when I was like about fifteen or sixteen everybody got to go out and date and stuff. She didn’t want me to date nobody. She said I was too young. What I ended up doing, I started going with this boy. He was eighteen and I was fifteen. My mother said he was too old for me. I just couldn’t see where he was too old cause I really liked him. I thought the sun rose and set in him. Seemed like he knew a whole lot more than I did cause his mother, she used to let them go out all the time and go to dances and stuff.

There were school dances and the pay was a quarter to get in. My mother was working nights. What I’d do is I’d keep my lunch money and Yvette, she’d always ask me about going to the dances. I didn’t want to say no, because I was embarrassed. Like at school they used to joke me and say stuff about you’re in high school now and your Mama won’t let you go to dances. I went. You don’t want to be left out of your group. Sometimes the dances would last until twelve or one o’clock. I would have my brothers watch for me and open the door so I could get in. My mother, she would always fuss but when she’d go to work, she didn’t have no say-so and I went to dances anyway.

Mama got so tired of it that she started checking up on me at school. I was going to school but I just didn’t want to stay home and I got so tired of her being so possessive that I started staying with a friend. I’d go to school every morning and when Mama would leave for work, I’d go home and pick me up some clothes. Every time she would come looking, I’d go out the back door or hide or something like that so she put the police to looking for me. The Chief of Police then was Mr. Cherry. I went down and talked to him and my mother. He says, “Now, Joan, you gotta stay at home. Just go home now with your mother and stay there.” I said, “Yeah,” and went home and left that same night and went back to a friend’s house. Then I heard my mother had been to see some lady and signed some papers and the police was looking for me again. They picked me up and told me I was going to a juvenile hearing because I was under the jurisdiction of my parents and I wasn’t obeying them.

I went to court and the judge said he was gonna put me on six months probation. He let me go and I went home for about two months. Later I had to go back to court and that time he put me on a year’s probation and said for me to not come back before him or else he was gonna send me to a girls’ home. My mother talked up for me, but about a week later I was there again. So he said he wasn’t going for it and there wasn’t gonna be no hearing or nothing, that he was gonna send me to that girls’ home.

Before all this, before going to Dobbs, the reason why my mother got so mad and all was that I was messing with this dude named Johnny. She didn’t like him cause she said I was too young. The judge told me I could live with my aunt. I did and she was even stricter than my mother. I couldn’t go nowhere on Saturdays and I had to stay there and I mopped, waxed, washed and ironed. She give me five dollars for allowance. If I went downtown, I had a certain limit of time to go and be back. When I came home, I couldn’t visit with anybody. If I went anywhere, I had to be back before six o’clock. If I didn’t have her permission, I couldn’t even leave the porch, much less the yard and here I was sixteen years old.

My aunt said, “Since you want to date this boy so bad, I’m gonna let you have company.” When I started taking company I wished I hadn’t, cause we were sitting in her living room. He couldn’t sit nowhere close to me or put his arm around me or nothing and kissing was out. My aunt was sitting in the next room and she’d keep passing back and forth in the room. No lights turned down or nothing. Johnny came one time and said this is it, the only time.

I was sleeping in the back room by myself. My aunt had a son and a daughter but they was real young. Since I was older, I slept in the room by myself. After they all went to bed, I would lock the door and sneak out by the window, and run down the street. Johnny lived over by the school, a good three blocks away, and I’d run the whole way. I’d go over there and knock and ask was he there and his sister, she’d say, “Yeah, he’s upstairs in bed. You can go on up.” So I’d go on up and wake him and talk to him. I’d stay until probably three or four and run home and jump in the window and get in bed and sleep like I’d been there all night long.

Johnny’s mother worked in a fish house where they cleaned crabs, and she wasn’t right down on none of her kids. She let a person do what they wanted to do. I wasn’t understanding anything my mother was saying about her then, but I can understand it now. If Johnny wanted to come in and lay up with a woman, his mother just wouldn’t have nothing to say about it. Only time she had something to say to me was if my mother would come up there looking for me. Well, Mother would come around saying stuff like, “I don’t want my daughter around here,” and she wouldn’t say nothing to her. I’d be upstairs and I’d be looking at her out the window. I’d hear her say, “If Joan comes here, please send her home. I don’t want to be calling the police to send them around here all the time. Joan is too young to be hanging out.” I’d just stand there and listen.

I thought it was real hip.

I thought I was real grown.

Training School

I was taken to Dobbs Girls’ School in Kinston. My social worker, who used to be a teacher, took me up there. She told Mother to have my clothes packed and she’d pick me up. The lady came to get me, took me to Kinston and put me in the Lennox Cottage at Dobbs. That’s the first cottage when you come through admissions.

I ran away from training school. It wasn’t that bad, but it’s hard being so young and locked away. I wouldn’t have run away but this lady accused me of talking loud in the lounge when it wasn’t even me. She was gonna make me buff floors until morning on my knees with an army blanket to make it really shine. I wasn’t going for it. I stepped.

Little Washington

After nine o’clock at night in Washington, there ain’t nobody on the street. You don’t see hardly even three cars coming down the highway unless they’re passing through town. I was totally all into the black community and I knew where I was. There wasn’t nobody there that was gonna hurt you as long as you didn’t cross that bridge.

Washington is the kind of town that’s way behind the times. You can tell there’s a lot of racism that goes on in town because there’s a railroad track that runs down the middle of town and from Fourth Street on back there’s nothing but blacks, the black community. On the left-hand side are all the whites so you know by what street people live on whether they’re black or white. If they say Tenth Street, you know you’re across the tracks in the black neighborhood. Most of the black streets are dirt streets.

The poolroom is on the corner of Fourth and that’s where all the blacks hang at. They go down there long about this*time of year, summer when it’s hot, and they drink wine and beer and hang. They sit around and listen to music and play pool, you know. There are a few clubs down there like the Elite and the American Legion and there’s Griffin Beach. A lot of blacks go to Griffin Beach. It’s not like a regular beach. It’s just a little road going way back up in the woods. When you get down there in the woods, there’s about three little shacks sitting up in there and there’s the whole big Pamlico River that you can swim in. It’s not that great. When you go up into a shack to change clothes into a bathing suit, it’s like some carpenter took some boards and built a hut out of them. Nothing at all elaborate. The whites go to a beach called Butcher’s Beach. They got a paved road to it and it’s real nice.

About four years ago my mother moved to Chocowinity. Chocowinity is an Indian name. Used to be Indians there, but there aren’t any settled there now. I don’t know where they went but just into history.

In Washington, there’s not what you would absolutely call integration. They integrated the schools in about ’70, I think. I was a sophomore and they moved me to Washington High School. You know, you just don’t hear of a black and white walking down the street hand in hand. You might go to Greenville, a college twenty-two miles away, and you might see it but you don’t see it in Washington.

Blacks and whites don’t really do nothing together. Not church either. We went to a Baptist Church. Jehovah’s Witness is integrated. The people that come up, they’re not gonna change. They don’t want to change. You live in a community like Durham or Chapel Hill, and you don’t come in contact with the kind of things like down there.

I remember there used to be a man, Johnny Rawls, down there in Washington. I worked for him in a cafe, a little small cafe. On the lefthand side was a door for the blacks and on the right-hand side was one for the whites. If you’d go on the side where the whites was, you just wouldn’t never get waited on. You’d just be sitting. They wouldn’t wait on you. It was air-conditioned on the white side.

On the black side, there’d be things like hot sauce bottles with some salt in them sitting up on the tables. There’d be a jar with some toothpicks sitting up in it. No napkins, no tablecloths or nothing, plus he had all this food stored and stacked up in one corner. When a black went in there, where you ordered at, you could see the kitchen part, the oven and all. You’d stand at this open window and they’d have pudding and desserts sitting up there on top of this deep freezer, and if they’d turn their back and you wanted to, you could reach your hand in there and get some. Ya ha ha ha. It was a trip! The white side was real nice.

I worked as a dishwasher. I did that in the summer and after I couldn’t get back into Washington High, I tried to go to work for Mr. Rawls. He wouldn’t accept me so I went to work for Mr. Levee at another restaurant. I had to make hot dogs there every day during the week and on weekends, too.

Some people stay in Washington, but most of my friends have gone. Young people don’t hang around there nowadays. Only place they can go to work is the garment factory of Hamilton-Beach or this yarn place, and they seldom hire a lot of young people. When they get out of high school and get their diplomas, there’s no real jobs for them there.

Washington is behind the rest of the world. It took two hundred years to get racism the way it is, and it’ll take just that long to get it straightened out.

Part II: After the Incident

After the jail, after the incident happened at the jail, I was just running down the street. My intention was to get to my cousin’s house, and when I got there I was asking him for help, you know, trying to explain bits and pieces. I guess it didn’t make sense what I was saying. We finally got it together, what had happened. He got just as uptight as I did.

When I left the courthouse, I could see a car coming up in the parking lot. When I left, if they were going by the testimony in the trial, the police came in and they were trying to find out where the jailer was and they went walking around back in the women’s section. He was locked in but they didn’t have no key. There was one key, like a big ring with all the keys to the whole courthouse. When I left out, I snatched up those keys that was in the door, so there was no keys at all in the whole jailhouse.

I could see the police cars coming up the street cause I could look right across the street at the house where I used to live, you know, and that’s where they thought that I was going. The police was looking and everything. My cousin started getting so uptight I started wondering myself if he was so nervous he was gonna jam me. So, I just left.

There was this liquor house, but I didn’t know nothing about it. I just more or less knew it was by them sitting on the porch and me passing by when I used to live on that street. I didn’t know nobody but I just walked on in the house like I wanted to buy me a shot of liquor. Pops was sitting out there on the porch and I said, “I got something I want to talk to you about,” and he say, “Okay,” and I say, ‘‘I’m tired and sleepy, can I lay down?” and he say, “Yeah, yeah okay. Go on back there and go to sleep. It’s alright with me.”

So I went back there and laid down on the bed. About thirty minutes later, he close up the house, came back there and lay down on the bed. I started telling him the main things that had happened and he said, “Wow, little girl, you got yourself in a whole lot of trouble, I got to tell you, you know. Well, I’m going to do everything I can to help you out.” I believe he was pretty high.

The next morning he got up, heard a knock on the outside of the door, locked my door and went on out. I was locked into the room. I didn’t get paranoid or nothing. He’d gone around the block and he told me he’d heard my name all on the radio, on TV, he said, wanting me for questioning about the death of the jailer. After that point, I just stayed.

The police kept coming up to the house. Like one night they came up and I was getting ready to come out of the bedroom. It was in the summertime. Down there where I live they cut off all the lights, raise the windows up and, you know, people sit on the porch till eleven, twelve o’clock because it be so hot to sleep. All the lights were out and I had walked out in the front. The floors were made out of cement. That’s how the old-timey houses were. I was walking down this little short hall into the living room, and I just happened to hear a car easing around the corner, just like damn police cars, you know.

I couldn’t run out the door or the back door cause I knew they probably had the police all around so the first thing I thought about was jumping in between the mattresses and this is what I did. Don’t ask me how I got in there or what made me do it. It’s just the first thing that jumped in my mind. I just got in there. The mattresses were about eight inches thick I know. They were this real heavy old mattresses that got feathers in them. It’s not hard like the ones they make now. I could fit plus it be sinking in the middle, and so I got under there and stretched my arms out trembling. You know it was hot as hell under there. I was scared to breathe. I heard them when they came in. They just busted in the house and told Pops they got a warrant to search the house and I heard them go upstairs.

Upstairs is where it looked like they had started making rooms but they didn’t, so it was just one big room and Pops had a whole lot of junk up there. He had this lady who used to come around drinking and all. She was laying up there with another man. She was drunk. They must have been into something because she was naked and the police hurried up and came downstairs. They came in where I was, shining flashlights on the bed. They shined them in the closet, and one of them raised up the mattress and I said, “Ohhhhhh, Gawwhhddd,” but he didn’t pull it all up, just raised it a little bit, got on top of the bed and then he left.

Police didn’t come back until the next day when I was sitting in there talking to Pops’ son. We was just sitting there talking and they come up on the porch. One man was talking to Pops and telling him they’d received a message that I was there and if he’d just give up that information they’d pay him, and Pops told them that money didn’t mean nothing to him, that this girl’s life meant more than money and he wouldn’t tell them anything.

They wanted to search the house again. So I got between the mattresses and Pop’s son laid up on top of me like he was asleep, and Pops raised hell saying, “Whatcha gonna come in here waking my son up and him sleeping and him out working all day?” So they left on out that time. I said, ‘‘Wow, things are sure enough getting hot. The next time they come they probably gonna tear this house apart.” I told Pops I should probably leave so it wouldn’t get him in trouble.

What I had intentions of doing was going to this old house, this twostory house up on Pierce Street. Nobody lived there. This guy I used to run with on the street, his family owned the house but nobody lived in it. It was furnished but it was so old on the inside, it just looked like every day it was gonna fall or cave in. I was gonna go up there. I knew how to get in and I was gonna try to hitchhike a ride out of town, but I was too scared. Pops’ son, he talked to me and said he had heard so much that he felt like they’d just shoot me down on sight. He wanted to try to take me to Greenville where I might could talk to a lawyer, and I told him I’d just hold. Then on Labor Day weekend, I saw my cousins outside the house. I thought maybe I could hitchhike a ride and go upstate somewhere, but it was broad daylight and I couldn’t just walk out there.

Somehow word got around to this sister named Margie and she found out that I was at Pops’. I didn’t even tell my mother where I was. I called her and told her I was alright but said, “I’m not gonna tell you where I am because as long as you don’t know, you can’t tell nobody!” I just didn’t trust nobody, you know. One night I was just laying on the bed and I hear somebody knocking on the window and I said, “Who is it?” and she said, “Margie. Tell the sister to come out the back door. I got a ride for her.”

I walked round to the back door and opened it up for her and she came in. She had another girl with her she called Sissie. She told me to hurry up and git clothes on cause we got a ride. She said, “Jerry Paul got it all set up and here’s what we’re gonna do — put your Mama in one car and your sister in another car.” My sister looks just like me. “When we leave, one car is going one way and the other car is going the other way because they got two tails out there. That’ll use up the tails and then, the third car, that’s the one we’re gonna use for you. We’ll let the other woman walk into the house and change wigs with you. Then she’ll stay in the house and you’ll walk out.” So that’s what we did.

Sissie got out of the car with Margie and I put on the wig that Sissie had on and walked out and got into the car. We rode away and went down to what they call Mister Ed’s and when we got down there, Jerry Paul’s car was waiting. We drove up beside Jerry’s car. I got out of Margie’s car and Margie and Jerry got into an argument about the damn wig. Margie wanted her damn wig back, and Jerry says, “Man, I’ll pay you for the wig. This ain’t no time to be arguing.” Ya ha ha! We got in Jerry’s car and rode on up to Chapel Hill.

When we got to Chapel Hill, we went over to this professor’s house. He like helped a fugitive for a couple of days, you know. The SBI issued me as an outlaw which means you can be shot down on sight. Jerry was making negotiations with Charles Dunn, who was head of the SBI then. The negotiations were that I was supposed to get a speedy trial and at no time was I supposed to be held in custody by Beaufort County officials. I was supposed to be held in an adjoining county or at the Women’s Prison but not at Beaufort County, so Charles Dunn agreed to those terms. I was supposed to turn myself in.

It was September 7, 1974, about three o’clock, I believe. Jerry came over to the professor’s house and picked me up and we went on over to Charles Dunn’s office. He read my warrants to me and told me I had been charged with first degree murder and that I would be held at Women’s Correctional Center. There was a lot of peoples out there, a lot of reporters and a lot of different political branches, so they didn’t bring me back out the front door. They took me out the back to a SBI car. When I got out there, this lady and man put handcuffs on me. There were about four other cars, eight policemen and a female officer was in the car with me. All of them rode over to the Correctional Center to make sure that I was in prison. After they called the dogs off, I just went on in the Women’s Correction Center and I stayed there from September 7 until February 26th when I made bond at $125,000.

Tags

Joan Little

Rebecca Ranson

Rebecca Ranson is a playwright who is a native of North Carolina. The author of over 30 plays produced in many cities across the country, Ranson bases most of her work on voices of the oppressed. (1986)