This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

Appreciation for this interview is extended to the Southern Investigative Research Project of SRC and to numerous individuals: Dr. Glover P. Parham, Emory O. Jackson, Demetrius Newton, Asbury Howard, and above all to Dobbie Sanders, Hosea Hudson, and the black steelworkers in the Birmingham district who created this story.

Fairfield, Alabama, is a company town, one of 17 residential areas near Birmingham built by the United States Steel Corporation. Nearly everyone who lives here works —or has worked — in US Steel’s local mills or mines.

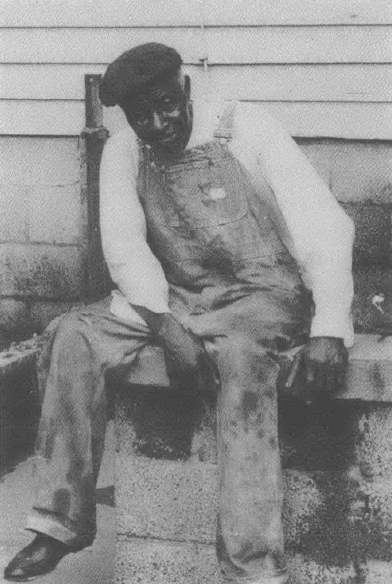

Dobbie Sanders is one of those former employees. Now 85 years old, Dobbie spent more than a quarter century working for US Steel, and the years have reshaped his body. His eyes are blurry; his feet, covered with callouses; his fingers, thick and rough — one with a tip missing.

Sanders lives in a small house on the corner of Fairfield’s Sixty-first Street and Avenue E. Each day, he walks slowly about his yard, dressed in a pair of greasy overalls. A passerby may see him squatting on the ground repairing a broken lawn mower, or leaning underneath the hood of a car, or fixing some electrical gadget. Sometimes, he sits for hours looking through one of the trunks in his yard, searching for objects that take him through his past: his baby sister’s dress from their family farm, a pair of his brother’s old gloves, records of outdated wage rates at US Steel, flyers from the International Labor Defense and various unions, his retirement papers, old insurance policies.

The objects that still fill Dobbie’s life are many and various, revealing his journey from a Mississippi farm to Alabama’s steel factories, from Birmingham to Chicago and back again. Like many black sharecroppers, he left the farm for higher wages and independence near the turn of the century. He found the company bosses instead. He went north looking for a means to advance himself, and enrolled in a school of electronics. He could make good money in the North, he says, but he felt he had to come home. And in Fairfield, he couldn’t find a job that met his new skills. He stayed, though, and persevered.

Today he sits on a yellow quilt, beneath a thin aluminum boat propped up by a single oar, and reads again the papers of his youth.

“Yessir,” he says as he rises from his quilt. “I’m a Mississippi man.”

Born in Bigbee Valley, Mississippi, near the Alabama line, Dobbie grew up with nine brothers and three sisters. They all began working at an early age. “My whole family sharecropped on the land of P.Q. Poindexter, a big white millionaire down in Bigbee Valley,” he recalls. “I worked from the time I first remembered myself. My father died when I was one year-two months old, but Mama told me he was a ditch digger. He dug ditches around the big farm to drain off the water.

“Mama raised us all. She was a mama and daddy too. She did a good job cause we didn’t have nothing. We did all the work and got nothing in return. Poindexter would credit us the tools, hogs, mules, cotton, corn seed and a pair of brogan shoes and jean pants. At the end of the season when it came time to add up, we would always owe him more money than we had to pay him, no matter how big the crop. We would always end up in the hole. We grew and raised everything, but he took it all. Course we had enough food cause we raised it. But that’s all we had.

“Every morning when the bell was rung, we had to get up and go out to the barn. Mr. Poindexter had hired a black man as the bell ringer; he was a wage-earner. When we got out to the barn to get our tools and stuff, it would still be dark. We would take our plows out to the field, and when the sun started rising, we were supposed to be sitting on our plows ready to work. The sun was the sign. And we would work and work and work until it got dark.

“Mr. Poindexter had hired a white overseer who rode through the fields on a horse telling us what to do. He never beat us; but Mama used to tell us how, when she was coming up, that the white overseers would beat the people with a whip. Sometimes we’d be out in the middle of the field working, and Mama would just bust out and start cryin and hollerin. She’d say, ‘If Bill was here, I wouldn’t have to be doin all this hard work.’ Bill was my daddy. I was small then, and didn’t understand why she was crying. But after I got up some size I understood.

“Lots of times people thought about leaving the farm, but if you tried to, the owner would take away everything you had. Your tools, mules, horses, cows, hogs, clothes, food, everything. But things were so bad that people still left.”

I just wanted to wear good clothes

“My oldest brother left home in 1919 and came to work in Fairfield at the US Steel Wire Mill. On May 8, 1922, I left. Mama had died, and I just wanted to wear good clothes like some of the rest of the boys. Hell, if you worked all the time and somebody took all you made, you’d leave too.

“After I left, I went and worked in the Delta at a levee camp as a wheeler, helping to pile dirt on the river bank to make a dam. I was paid about $1.75 a day. I stayed there a little while and then left. I hoboed, caught rides, and walked my way to North Carollton. That’s near Yellow Dog, Mississippi. I worked there for awhile laying ‘y’ shaped tracks at the end of railroad line until they laid me off. Then I hoboed on trains and walked until I got to Sulls, Alabama, working my way on up to Fairfield.

“In Sulls, I worked in the mines with my brother, Jim. I only worked for a month and had to quit cause I was too tall for the mines. My head kept hitting up against the roof. I told my brother I was going up to Fairfield to get a job in US Steel’s Wire Mill and stay with another one of our brothers, William. Jim said OK, but told me, ‘Make sure you work enough to feed yourself.’

“And I did. When I got to Fairfield I stayed with William and his wife in Annisburg, next to Englewood.* I started working in September, 1922. William’s wife would go down to the company store and get food, and the company would deduct it from my paycheck every two weeks.”

When he first entered industry, Dobbie Sanders followed a path beaten by thousands of black Southern workers before him. Even before the Civil War, blacks played a crucial role in Southern industry, and especially the iron business. As far back as 1812, 220 slaves were owned by the Oxford Iron Works of Virginia. In the Tennessee Cumberland River region, one iron company owned 365 slaves in the 1840s, and 20 other establishments in that area worked more than 1,800 slaves. In 1861, the Tredegar Iron Co. of Richmond employed the third largest iron-working force in the United States, and half of the 900 men were slaves. Altogether, an estimated 10,000 slaves worked in the South’s iron industry.

Before the Civil War, Selma had been the major site of Alabama’s iron works, but in 1865 the city fell and its plants were destroyed. Other coal and iron plants were soon constructed throughout the state and began to grow and merge. In 1871, Birmingham was founded as the ideal location for an industrial steel complex which required easy access to coal, iron, water and transportation. Eventually the Tennessee Coal & Iron Co. (TCI) became the uncontested leader in Alabama’s steel business, and in 1892, it moved its headquarters to “The Magic City,” a name Birmingham soon earned for its phenomenal growth. Fifteen years later, J. P. Morgan absorbed TCI into his US Steel empire.

In 1910, 13,417 blacks were employed in US blast furnace operations and steel rolling mills, the vast majority in the lowest paying, dirtiest, most tedious jobs. At this time, almost three-quarters of all common laborers in the steel and iron industry were black, though they were only 8.2 percent of the skilled workforce and 10.7 percent of the unskilled workers. Of those few skilled black workers. almost 40 percent were employed in Alabama —635 men.

Like Sanders, many of these workers had recently come from nearby farms in search of freedom from their hard times. Most didn’t find it.

“When I started working at US Steel’s Wire Mill, the company owned the houses, food and clothing stores, hospitals, schools, churches, everything. And they deducted everything out of your pay check — food, clothes, rent. Sometimes we’d work the whole pay period and time come to get paid, and we’d draw nothing but a blank slip of paper. That mill was rough. When I started working there in 1922, we were doing 10-hour shifts at $2.45 a day, as many days as the man told us to come in. Later, they went on the 8-hour day at $3.10 a day, but we still had to work 10-hour shifts. We had no vacation, no holidays, no sick leave, no pension, no insurance, no nothing. It was rough.

“I went ahead and got married in 1927. Most of the women in town did clean-up work. A lot of them worked in the basements of Loveman’s and Pizitz’ Department Stores shining shoes and scrubbing floors. No dark-skinned women drove the freight elevators even.”

Just got tired of the whole thing

Dobbie Sanders had come to Fairfield frustrated with working long hours and getting nothing for it. Now he found himself in the same situation.

“One day back in ’27 or ’28, I just got tired of the whole thing and quit work. I enrolled in the L. L. Cooke School of Electronics in Chicago. L. L. Cooke was the Chief Engineer of Chicago. Even though I had only finished the third grade, I was a good reader. I used to read all of my brother’s books. I’m a self-educated man.

“When I was in electronics school, I learned how to make and fix door bells, wire up burglar alarms, wire houses and everything else. I’ll even wire you so if anybody touches you, you’ll ring. I wired up that old dog pen out there just so it would touch the old dog up lightly when he tried to step over the fence. It’ll touch you up lightly too if you try to git in.”

Sanders points with pride to a thick, dusty electronics textbook printed in 1927 by L.L. Cooke Electronics School, Chicago, Illinois. Many sentences in the book have been underlined, with numbers from 1 to 10 marked beside them.

“You see, at the end of each chapter there are ten questions. The answers are in the chapter. I put the numbers of the questions next to the answers. Then I underlined the answers. I made everything in that book, and I read and studied every page of it. That’s why I can fix so many things.

“I can fix everything except a broken heart, can’t fix that.

“After I left Chicago, I went on to Detroit. I was making good money there, too, just fixing things. But I came on back to Fairfield. You know how it is bout home. You know everybody and everybody knows you. Plus, when I was away I was living with other people. You know how it is.

“So when I got back here, the head of the school in Chicago called the people at US Steel, and told them what I could do. But they said they wasn’t hiring no colored electricians. They still made me do electrical work sometimes, but they just didn’t pay me for it.

“US Steel is one of the dirtiest companies in the world. And if the working people of this country would ever get together, they could run the whole thing. That’s why I like that worker/farmer form of government.”

It was all about a higher standard of living

While working in Fairfield, Dobbie Sanders became involved in a number of groups fighting for black and working people’s rights. One was the International Labor Defense (ILD), organized by the Communist Party in 1925 to fight extra-legal organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan. ILD members had become active in highly publicized campaigns to free Tom Mooney, Warren Billings, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. In 1931, the ILD came south as the main organizers of the Scottsboro Boys’ defense in Birmingham. Over the next few years, the ILD was able to turn national attention to the South and to the trial of the nine young blacks facing the death penalty on charges of raping two white women. Blacks and a few whites throughout the South supported the ILD and the Scottsboro Boys, contributed money from church offerings and attended rallies. At one Birmingham meeting, 900 blacks and 300 whites turned out.

“Yes, the ILD was in here with the Scottsboro Boys, and I was right along with them. I used to pass out leaflets for them down at the plant. I would stick em in my lunch bucket and tie em round my waist and ankles. On the way inside the gate, I would open up my bucket, untie the strings and let the wind blow the leaflets all over the yard. I’d just keep steppin like nothin ever happened. There’s always a way, you know.”

But he is reluctant to talk much about the organization’s programs. He laughs, “You go ahead and talk some. I done already gone too far. Why, I been 75 miles barefoot, and on cold ground, too. But I’ll just say this: it was all about obtaining a higher standard of living.”

Sanders was also a member of the United Steelworkers of America, which began organizing in Alabama in the late 1930s and joined the state’s long tradition of integrated unions. That tradition started with the United Mine Workers before the turn of the century. By 1902, the UMW had organized about 65 percent of all miners in the state, a majority of them black. Racism and social segregation were continual problems for the union, but even in 1899 a few blacks were able to hold the presidency of locals that included white members. A series of long strikes took place in the first decades of the century, one from 1904 to 1906, which weakened the union immensely. But the UMW kept returning — in the teens, in the 20s, and again in the 30s.

Throughout this period, attempts were made to organize the steel industry, but that feat was not accomplished until the birth of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1936. Under the leadership of UMW president John L. Lewis, one of the top priorities of the CIO was the organization of the steel industry. The CIO established the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) for that purpose, which later grew into the United Steel Workers of America (USWA).

Dobbie Sanders joined USWA in its early years. “Before the union came in here in the 1930s,” he explains, “it was rough. We didn’t have any say in anything. I was one of those who helped get people signed up. We had to slip and sign our cards and pay our dues. When the Steelworkers ran into trouble, they’d just call in the Mine, Workers. Them boys would come in here from Walker County with snuff running down their chins, both black and white. And they didn’t take no stuff. If it wasn’t for Ebb Cox and the Mine Workers, we never would have got a union.”

Cox was one of the Steelworkers’ most determined leaders, encouraging workers to join the union wherever he could — in churches, in the bars and on the streets of Fairfield. Tall and lightskinned, with no formal education, he became one of the staff. He was the object of much anti-union and anti-black violence in Mississippi and Georgia as well as Alabama, but he continued his relentless fight for the union. He was eventually elected the first black member of the Alabama CIO Executive Board.

Dobbie Sanders was also a union leader in Fairfield. “I put food in a lot of women’s and babies’ mouths by writing out Step One-and-a-Half in the promotion line in the wire mill. Step One was on the broom. Step One-and-a-Half was classified as the “helper,” even though you’d actually be doing the work (of the person on the Step Two job). This was so the company could get away with paying Step One-and-a-Half wages even though you’d be doing Step Two work.

“After the union had come in, I wrote a provision that said that after so many hours on the job, a man had to be given a chance to bid for the job and be paid the right wages. I took it to my supervisor, and he couldn’t do nothing but accept it. Hell, before this thing was written up, they’d keep a man in Step One-and-a-Half for a hundred years. Yessir, that mill was rough.

“And we had a lot of people working against us too. Not just the company, police and sandtoters (informers), but most of the preachers. Man, them preachers is a mess. Most of em ain’t no good. Brainwashing, that’s what they all about. They should have been race leaders, but instead they are race hold-backers. And the people who support them are crazy, too. Does it make any sense to pay somebody to hold you in the dark? These preachers go around here charging people to keep them looking back. Goin around here tellin people bout heaven. How you gon git to heaven after you die, and you can’t even get to 19th Street in downtown Birmingham when you are alive. When you die you can’t even go to the undertaker, they have to come and get you. So how you gon go to heaven?”

Dobbie stayed at the mill for more than 25 years, doing the same work at the end that he had when he started. “I retired on March 31,1959,” he remembers with the precision that he has for only a few significant facts of his life.

Since then he has lived at the corner of Sixty-first Street and Avenue E in Fairfield, surrounded by the memories of his life. “I tell you,” he says softly, looking up from his boxes, “if I could go back through the whole thing again, I’d git me one of them easy shootin guns, the kind with a silencer on it. And I’d be a killer.”

*Annisburg and Englewood were the first areas built for black families working for US Steel. Although now a part of greater Fairfield, the areas were originally separated from the white neighborhoods by a row of bushes that Dobbie Sanders calls “The Iron Curtain.”

Tags

Groesbeck Parham

Groesbeck Parham, a native of Fairfield, Ala., still lives in the Birmingham area where he is preparing for graduate study. He has gathered extensive oral interviews and written documents on Birmingham’s black labor history. (1976)

Gwen Robinson

Gwen Robinson has taught history in Dartmouth’s Black Studies Program and is currently directing a research project in Chicago on minorities in the construction industry. (1976)