I’ll Just Keep Running

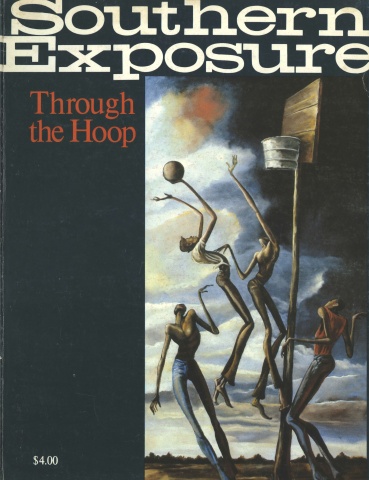

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

April 17, 1977. It is 9:00 a.m. on a cloudy spring morning, the temperature and humidity both hovering at 70. I am in Opelousas, Louisiana, toeing the starting line for a 10-mile road race with 35 other hopefuls.

Hardly awake, I wonder what I’m doing here — a four-mile-a-day runner (I hate the word jogger) who accepted my friends’ invitation to drive up from Baton Rouge for the race. But my friends are marathoners and former collegiate track stars. This is just another run for them. For me, used to circling an asphalt track in a city park with my dog bounding at my heels, it is a marathon.

Opelousas is a sleepy little Cajun town whose only claim to running fame is high hurdler Rodney Milburn, gold medalist in the 1972 Olympics. Milburn, in fact, is on hand for the race, which is sponsored by the Opelousas state troopers.

The troopers obviously lack experience in putting on races. They serve coffee and doughnuts as a pre-race snack but have provided no toilets to accommodate pre-race jitters. They have, however, invited another Olympic hurdler, Willie Davenport, to fire the starter’s pistol.

“Aren’t you going to run, Willie?” I ask, hoping for sterling company in my maiden 10-miler.

“Hell,” drawls Davenport, “put together all my races and I may have run 10 miles.”

The race starts near the highway, which appears to be in the legendary middle of nowhere. I stand well back of the pack and assess my rear-guard companions. A middle-aged man in cut-off dress pants, a T-shirt that reads Cajun Power, leather workboots and red bandana already complains of blisters. He’ll ride to the finish, I silently predict, thankful the troopers will be patrolling the course.

A black man in football pants and abbreviated T-shirt looks like a grid star gone to fat. A junior-high trackster in black high-top sneakers cracks his knuckles. And then there’s me, former devoted creampuff and athletic outcast who two years ago discovered running and has preached and practiced with the zeal of the convert ever since. We are the motley crew.

Davenport fires the gun and the pack leaps forward. I plod forth at my eight-minute pace, the last one past the starting line. Davenport catches my eye. “Bye,” he says, heading for the doughnuts. Did I detect a note of irony?

Assaulted by a stitch in my side, I reach Mile Two in 16 minutes. The junior-high kid, puffing along beside me, says he’s never gone more than two miles consecutively. My pain sharpens, and I slow to a walk and let him go.

I resign myself to an invalid’s pace. After all, I didn’t come here to win the race, or even to finish it. At 9:30, the day is still cloudy, with sporadic light rainfall. The asphalt country road is disturbed by few motorcars; this is the hour when good Cajun people are singing hymns in church or sleeping off the rigors of last night’s sortie to Webb’s in Lafayette.

Barbed-wire fences thick with honeysuckle line pastures on either side of me. Hollandaise-colored buttercups sprout from ditches. Cows and new calves blink at me, and three horses stare from a rise. After a mile, I resume running. The smell of honeysuckle makes breathing seem easier. At Mile Five, I pass Cajun Power.

“I saw you resting back there, cher,” he scolds. “Now, here you come again.”

“Yeah,” I gasp. “It’s the tortoise and the hare all over again.”

“Well, you better not stop again, no,” he warns in his thick patois. I picture him climbing over my back in a mile or so, but I press on. In a curve of the road dark with the shade of pin oaks, I pass a black family — grandfather and three kids — leaning on a wooden gate. They gaze at me unmoving. “Good morning!” I call, and they raise their hands in tentative greeting.

I catch up with Junior High, and we fall into a companionable stride as he tells me he runs the quarter-mile and he throws the discus for the Arnaudville Junior High track team, a crew that hasn’t won a meet this year. I ask his best time in the quarter. “Oh, about a minute and a half,” he says. Pondering that information (perhaps he runs the quarter while carrying the discus?), I notice his breathing is labored. Now it’s his turn to drop back.

A half-mile later, I pass Mr. Touchdown. He huffs and puffs fiercely but looks strong. I’ve passed three men (well, two men and a boy), but I can’t expect this to last. Nevertheless, here I am at the six-mile mark, feeling pretty good. No more side stitch. I’ve never run more than six miles before. I think I’ll just keep going.

Matter of fact, I’d better. I haven’t seen a trooper in three miles. I’m thirsty, too, but I’ve seen no aid stations throughout the race. Did the troopers think coffee and doughnuts would suffice?

At Mile Eight, momentarily menaced by a German shepherd, I lose some time. My right heel stings with blisters. My body gradually adopts an “old-person” stride: steps cut short, arms pulled in close, chest sagging, as though to protect me from my growing fatigue.

The last two miles seem endless; I don’t know how far I still have to go. I check the road behind me: Cajun Power, Mr. Touchdown and Junior High are nowhere in sight. I contemplate tears: too much effort. I’ve come too far to quit now.

I spot a police car. A trooper directs me to turn right. “How much farther?” I gasp. “Three tenths of a mile.” Aw riiiiiight! A piece of cake. I urge my numb legs into a sprint. The road is full of potholes, each one a ravine ready to swallow me. The troopers at the finish line yell, “Kick! Kick!” You fools, I mutter, I am kicking.

I lunge across the finish line. My friends stand there, grinning like idiots. They don’t believe I’ve done it. Neither do I. Thirst overpowers me. Someone gives me Gatorade, but it tastes like pure salt. I grab for water, can’t stop guzzling it. Has champagne ever tasted so sweet — or so richly deserved? I feel like I’ve won a gold medal. Down the road, I spot Cajun Power, beginning his kick. His red bandana bobs like a victory flag. I stand at the finish line, cheering him on.

Tags

Ruth Laney

Ruth Laney is a free-lance writer based in Louisiana. Her work has appeared in Women’s Sports, The Runner, Track & Field News and Louisiana Life. Her story, “I’ll Just Keep Running,” appeared in Southern Exposure’s special issue on sports. (1981)