The Innocence of James Reston, Jr.

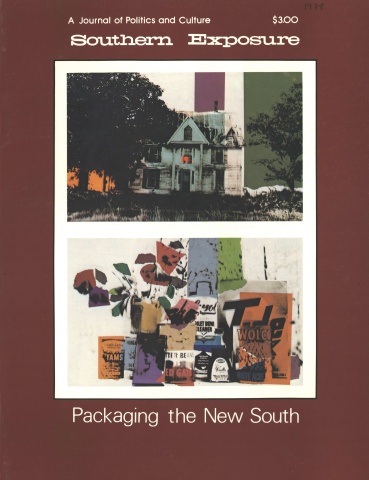

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

In his introduction, James Reston, Jr., lists what he says are the “five crucial questions” arising out of the case of Joan Little, the young black woman charged with and acquitted of first-degree murder in connection with the death of an elderly white jailer who, she said, attempted to assault her sexually in her Beaufort County, North Carolina, jail cell in the early morning hours of August 24, 1974:

In a sexual assault, does a woman (or a man) have a right to kill her (or his) sexual attacker? Is the level of decency in North Carolina and the nation above the spectacle of human executions? What recourse does a prisoner in jail have to the brutality of jail authorities? How has the lot of the black citizen changed in the rural South? And finally, despite the flood of flowery acclaim for the South that Jimmy Carter’s election has brought, how new is the New South?

The questions are excellent. Unfortunately, the answers are not to be found in The Innocence of Joan Little: A Southern Mystery. The reasons lie with both the form and the substance of the book. Using the Japanese film “Rashomon” as a model, Reston provides what is essentially an oral history of the affair, using transcripts of fifteen lengthy interviews of principals in the case. Fifteen conflicting views of any event, presented uncritically, would be difficult enough to sort out if each person were telling the truth to the best of their ability. In this case, however, a majority of the participants are so thoroughly caught up in creating obvious and outright fabrications, and in inflating their own roles, that a reader unfamiliar with the Joan Little trial would come away knowing less for having read this book.

Occasionally, when Reston pauses in the transcripts to make an observation of his own, his analysis is excellent, as here, when discussing the strategy of District Attorney William Griffin:

Griffin never understood that the Joan Little case had long since travelled beyond legalities, that the courtroom was simply the stage for a far broader spectacle in which only lawyer-publicists belonged, and that the horror of the audience outside, stretching now beyond state and national boundaries was sustained as much by the danger to Joan Little’s life as anything. Had Griffin acceded to reducing the charge to second-degree murder or manslaughter back in November, the nation would never have heard of Joan Little and the case would have been handled “the country way” from start to finish.

It is both a pity and a loss that Reston, who covered the trial for television and the newspaper Newsday, who perceived the crucial issues at the outset, and who could be so incisive in the relatively few instances in the book where he relied on his own analytic skill, chose to present this kind of oral history of the Joan Little case.

In the entire book, the single bit of new information I found about this affair was that Joan Little’s and Jerry Paul’s hometown of Washington, North Carolina, was also the birthplace of Hollywood film mogul Cecil B. DeMille. Of the interviews themselves, the only ones I found credible, in the main, were those given by prosecuting attorneys William Griffin and John Wilkinson, and defense psychologist Courtney Mull in — and only Ms. Mullin’s did I find wholly believable. (Judge Henry McKinnon was also believable, but his limited role, i.e., approving a change of venue from Washington, NC, to Raleigh, while important, did not make his observations especially valuable.)

The main problem with oral history is that people lie to you. The folks in Reston’s book are no exception. Now “lie” is a pretty strong word. Someone kinder might say that the difficulties involve “selective recollection,” “disremembering,” “exaggeration,” “fudging on details,” etc. In any case, good research would have been Reston’s best safeguard against such occupational hazards, research which would have made it possible for him to ask the right questions and critically evaluate the answers. Furthermore, given the limited space in a book like this, the truthfulness of a person’s testimony ought somehow to be reflected in the space allocated for their words within the author’s larger mosaic. Obvious lies ought simply to be discarded. Unfortunately, that has not been Reston’s practice in The Innocence of Joan Little.

Here are a few of the more egregious errors that I found among the interviews:

Sheriff Ottis “Red” Davis. The sheriff’s account of Beaufort County’s recent history of racial harmony is simply at odds with the facts. If time had not exactly stood still in eastern North Carolina until the late 1960s, it was dragging its feet. And almost nowhere did it dig in its heels more than in Beaufort County — in matters of voting rights, jury service, public accommodations, school desegregation and, yes, police brutality. But, to hear Sheriff Davis tell it, Washington, NC, had a better racial climate than Chapel Hill, or Tuskegee, Alabama.

District Attorney William Griffin recalls his thoughts when his summer vacation in New Jersey was interrupted with news of the murder and escape:

My initial reaction was that if things like that are going to happen, they’ll happen in Beaufort County. All the messy cases in my district seem to take place in Beaufort County. People are more litigious there, and the county has quite a few sorry folks, white and black.

At another point in his narrative, the sheriff mentions the illness of a key law enforcement official on several occasions. That illness, he once told me, was a severe, debilitating case of alcoholism. The sheriff never failed to make two related points to journalists who interviewed him, and does so here. First, that after spending an hour and a half with an out-of-town reporter, he was surprised to find himself portrayed as a “redneck.” He refused to be specific, but he apparently was talking about an article I wrote for the magazine New Times in which I didn’t let him get away with the kind of self-serving nonsense he is fond of pawning off on the media. Which brings us to his second claim, that he is beloved by the blacks of Beaufort County. Sheriff Davis consistently points out that he got “ninety percent of the black vote” when he was elected sheriff. Unfortunately, he always fails to state whether he is talking about the Democratic primary or the general election. A little prodding from Reston would have revealed that Davis has no figures at all for the Democratic primary, and is referring to the general election, in which ninety percent of the black vote means little, given the reality of Beaufort County politics.

Ernest (Paps) Barnes, Margie Wright, Golden Frinks and Celine Chenier. The various accounts given by these individuals of the events immediately following the killing of Clarence Alligood are so flagrantly divergent (as is that of Jerry Paul) and conflicting that they almost go beyond the realm of myth and epic. Each must have his or her own reasons for their exaggeration, some of which are obvious. Celine Chenier was under increasingly debilitating pressure even before her involvement with Joan Little, as leader of Action for Forgotten Women, the prisoners’ rights organization. And Golden Frinks was understandably bitter at being shut out of the most important case of his career as a civil rights leader for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

Jerry Paul. There came a point in the Joan Little trial when reporters stopped believing anything Jerry Paul told them outside the courtroom — and for good reason. Almost for his own amusement, it seems, he spun tales of secret witnesses, Polaroid pictures of the crime taking place and all manner of bizarre and palpably false information. Likewise, he has never provided a full accounting of the massive fundraising efforts made on behalf of his client.

In the course of two chapters devoted to his memories of the case, Paul manages to badmouth the efforts of almost everyone else involved in the case, including his law partners (who have since left his firm), SCLC, the Black Panthers, feminist groups, leftwing groups like the Communist Party, and the news media. Each was, by Paul’s account, foolish, misguided, naive, incompetent, and/or subject to the manipulations and grand design of the chief defense attorney.

Of his client, he recalls:

I could not sell Joan with her negative side coming out. She has that basic personality flaw that her environment created in her, and it’s still there. She’s not an honest person. That doesn’t mean she committed this crime. Beyond that, Joan is an actor, an impersonator. The psychiatrist to whom I later referred her told me: “Joan Little is not a real person.”

(At another point in his monologue, Paul says that he refused to refer her to a psychiatrist, thinking he could do a better job himself.)

It should be noted that throughout the trial and for some time afterward, Jerry Paul has been under a good deal of pressure apart from the fate of Joan Little and the disintegration of his law firm: a dying child, jail sentences for contempt of court and disbarment proceedings. Any combination of these things may have contributed to his mesmerizing mixture of messianism and megalomania.

Terry Bell. This alleged “secret witness” was one of Paul’s more outrageous ploys. It was so outrageous, in fact, that the only reporter in the press corps who fell for it was James Reston, Jr. In addition to causing a good deal of useless legwork for other reporters (whose editors in New York and Washington wanted to know what was going on), this scoop prompted a distinct cooling of enthusiasm on the part of Reston’s editors at Newsday. Why such an embarrassing incident is referred to, much less given an entire chapter, is beyond comprehension.

The list could go on and on. Deputy Sheriff Willis Peachey, surely one of the more sinister presences in the Raleigh courtroom and at the scene in Washington, is permitted to explain away an almost criminally negligent and botched investigation. City Councilman Louis Randolph is allowed to justify a lack of vigorous black leadership in the county.

There are also smaller factual errors. The respected criminologist Herbert MacDonnell becomes the “notorious Hubert MacDonnell.” (In his earlier account for the magazine of the Sunday New York Times, Reston twice reported that Joan Little faced the electric chair, although North Carolina actually uses a gas chamber.) There is no index.

In his introduction, James Reston, Jr., characterizes his story as a

. . . circumstantial case of murder and rape, with two distinct theories of how the crime(s) happened, each supported by considerable evidence (not all of which was presented to the jury or reported to the public in the press). As the chronicler, I have endeavored to relate both theories with equal passion. Each theory of the case was based largely on a view of the character of Miss Joan Little — heroic or villainous — and judging the defendant was largely a matter of predisposition.

Yet Reston later says that he found Joan Little’s character “indistinct to the end,” and the chapter that bears her name is composed almost entirely of transcripts of her trial testimony and cross examination. If Joan Little’s character is so central, where is the revealing interview with Joan Little? Where are the long interviews with the jurors, with the presiding judge?

The author’s promise of “equal passion” turns out to be an equal lack of passion, punctuated only with obscure literary references and glib, one-word characterizations of people and their actions. A lecturer on creative writing and author of two novels, Reston seems throughout more intrigued with the literary formula of his “mystery” — as he nearly admits in his introduction — than with the pursuit of the questions he knows the case raises in real life. His failure to provide an interview with Joan Little — who was willing and able to cooperate — fits well with the construction of a fictionalized mish-mash of competing egos fighting over her life, but it is also the final proof that the book is not a serious investigation of how justice works in the South, and more importantly, what American justice means for its victims.

Tags

Mark Pinsky

Mark Pinsky is a freelance writer based in Durham, North Carolina. (1982)