Jimmy Carter and “Populism”

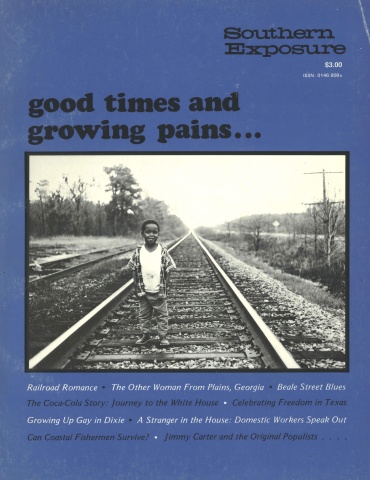

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 1 "Good Times and Growing Pains." Find more from that issue here.

Beginning in the spring of 1976, when the nomination of Jimmy Carter first became a distinct possibility, and extending through the ensuing campaign and into the first hundred days of the Carter presidency, a fairly uncommon ideological question intruded into mainstream American politics: “Is he a populist?”

The question was asked with great longing by some, with considerable anxiety by others, but, in either case, the possibility of presidential “populism” acquired, for awhile, a fair amount of notoriety. Now that Mr. Carter has, in his own interesting fashion, provided impressive evidence that he is not a populist, the entire episode might be put aside as a temporary national aberration were it not for the fact that the implicit issues raised — including the very meaning of modern political language — cast such revealing light on the rigidity of contemporary American politics.

Carter himself precipitated the discussion by his quiet acknowledgement, made quite early in his bid for the Democratic nomination, that he was indeed a “populist.” The term evoked images of legions of Southern and Western farmers striving, some time in the late nineteenth century, for more economic justice and, as such, was consoling to many Americans of progressive persuasion. But before Carter’s early primary victories, his pronouncement stirred little general interest — especially east of the Hudson River where manifestations of the original Populist impulse had been virtually nonexistent and where the topic has ever since remained cloudy. But by the time Carter had demonstrated his growing electoral muscle in the Pennsylvania primary in the late spring, a number of Northeastern urbanites, including a banker or two, began to interest themselves in the populistic proclivities of Jimmy Carter. The serious investigation of Carter’s ideological presumptions was upon us.

The inquiry was beset by a certain amount of organic confusion from the outset, for any measurement of Carter’s populism necessarily depend-ed upon some sort of understanding of what “Populism” was. And this, of course, meant grasping the essentials of the original specimen which appeared in the late nineteenth century. A generation ago, the noted historian, C. Vann Woodward, did his best to provide a calm, scholarly description of historical Populism through his brilliant biography of Tom Watson, the agrarian captain from Carter’s home state of Georgia. Some years later, Woodward followed with an investigation of Populism throughout the South, published as part of his magisterial rendition of the post- Reconstruction era, Origins of the New South. But though Woodward presented an impressive case that Populism in the South was serious business, and though subsequent scholarship has offered evidence that it was serious business in the Western granary as well, the Gilded Age reformers continued to receive considerably more condescension from twentieth-century Americans than serious inspection.

Despite the efforts of those historians who wrote in the Woodwardian tradition, Populism did not materialize as a progressive movement in our history books. Rather, it remained somewhat odorous (either faintly or malevolently) and, above all, vaguely defined. In this fashion, the agrarian revolt was dimly perceived as some sort of mass popular movement unencumbered by serious intellectual content. The conclusion seemed to be that a Populist was someone who was “for the people,” but precisely how he or she proceeded to demonstrate this loyalty remained obscure.

Contributing to the uncertainty over time were a number of Eastern-based academics — notably Richard Hofstadter, Oscar Handlin, and Daniel Bell — who seemed to restrict their research to local libraries where primary materials on populism were necessarily in short supply. In their hands, Populism was “irrational,” “zenophobic,” and altogether something from which Americans were well spared. Indeed, Jimmy Carter’s willingness to associate himself with such a questionable historical experience indicated he might not quite measure up to the minimum requirements of presidential stability.

From such premises, then, the investigation of Jimmy Carter’s populist roots proceeded. The results were contradictory. It was discovered that his maternal forebears in Georgia had been disciples of Populist Tom Watson, and that they shared with Watson the conviction that credit merchants in the South, and the American banking system generally, were systematically exploiting the great mass of American farmers. Building upon this conviction, Watson, and presumably Miss Lillian’s parents who supported Watson, developed some rather far-fetched ideas about the proper structure of the American economic system.

On the other hand, Jimmy Carter’s paternal forebears were credit merchants who, like their counterparts elsewhere in the South, managed to acquire title to much of the surrounding countryside. As such, from a Populist perspective, they were part of the problem, not part of the solution.

The 1976 presidential candidate seemed to blend these sundry ancestral impulses into his speeches with semantic ease. The poor needed help and he would give it; on the other hand, he was a fiscal conservative, and government was too big. He worked well with people who worked well with Nelson Rockefeller; he also worked well with Andy Young. He even, very briefly, worked well with Ralph Nader. The signals were, indeed, unclear. From beginning to end, the debate about presidential populism was conducted without much clarifying assistance from the principal subject himself.

In fact, the inquiry by all parties was misdirected from the outset, and little blame can legitimately be placed on Carter for the disappointment of liberals over his economic policies once he settled into the White House. As a matter of fact, the plaintive hope of so many people that Carter would resuscitate the American progressive tradition by acting in “populistic” ways reveals rather more about the erosion of the democratic environment in America than it does about the political maneuvering room available to a president elected within the constraints imposed by that environment.

The confirming evidence for this assessment comes not so much from presidential actions as it does from a clear understanding of what historical “Populism” actually embraced and what modern “liberalism” does not embrace. Populism was a mass movement of some millions of people over a score of states scattered across the South and West. It was autonomously based — that is to say, it was grounded in an institution that offered specific political goals in the name of the people who comprised the institution. Ideologically, Populism represented a critical analysis of the particular structure of finance capitalism at a time when the captains of industry and finance were in the process of defining the future ground rules for social, economic, and political conduct of twentieth-century Americans. Populists regarded these ground rules not only as inherently undemocratic and exploitive, but corrosively restrictive of popular democracy itself. However, since they lost their struggle to place a number of curbs on the spreading power of the corporate state, modern politics in America has necessarily operated within the much narrower perspectives that Populists worked to avoid.

One consequence of our constricted modern view is that we have been unable to understand the original Populists. However, in terms of Jimmy Carter, one thing is clear. Though Populists strenuously attempted to hold their political spokesmen to support of the structural economic goals of their movement, they had far too sophisticated an understanding of authentic democratic politics to place their hopes for such fidelity in the politicians themselves. Instead of deferentially hoping that their spokesmen were “good Populists” who would not betray them, they attempted to maintain their movement in such purposeful and democratic order that they themselves would be able to determine who those spokesmen would be. “The people” themselves, organized and politically informed through their own actions in their own movement, were to provide the necessary guarantee that any political problem inherent in the infidelity of candidates would take care of itself. In short, they did not wait, apprehensively, for signs that their own spokesmen would or would not, in contemporary parlance, “sell them out,” for the simple reason that they did not believe authentic democratic politics could be created from on high by a “leader” — even a presidential leader.

Indeed, in one sense, the culturally confined participants in modern American politics who have described the original Populists as “irrational” were correct. From such a perspective, steeped as it is in resignation masking itself as sophistication, it is indeed “irrational” for anyone in modern America to aspire to the kind of democratic goals the Populists envisioned.

The verdict is clear. The Populists lacked sophistication. They did not know what they were up against. They lacked the wit to be intimidated by the constraints of political life in the corporate state, with its massive economic oligarchies, with its privately financed elections responsive to those same oligarchies, with its resulting culture of loyalty to the prerogatives of corporate elites to shape the political process itself.

The Populists did not understand that their battle should not have been fought because it was not going to be won. So failing to understand, they worked together for many years, first as a small band in the Southwest, then as a mass constituency of “plain people” across half a continent. So failing to understand, they developed their own sense of autonomy and self-respect, their own democratic analysis of the world they live in, their own Jeffersonian-style vision of a society where people rather than corporate combinations determined the rules of civic dialogue. So failing, they dared to aspire in behalf of their own vision of human possiblity. This, indeed, was their fate.

But this is also their legacy. It has little to do with Jimmy Carter. He is as confined by the rules of modern American politics as any of the rest of the population. As the original agrarian reformers of Gilded Age America knew, democratic politics does not begin with politicians, even presidential politicians. It begins with the self-respect of individual people, and eventually the organized self-respect of many people. If the evidence of history is any guide, Americans will not have a populist president until we first develop a mass popular constituency. For such is the stuff of authentic democratic politics. Unfortunately, such a concept of democracy is a topic, indeed a way of thinking, that is not easily fathomed within the constraints of “modern society.” Contemporary progressive politics persists without relation to the building of mass democratic constituencies.

Eighty years after Populism, the Democratic Party is little more than a repository of vaguely progressive impulses, an organizational shell so undefined and helpless it was taken over by 100,000 kids in behalf of McGovern in 1972 and taken over four years later by a provincial politician with wholly predictable ties to his own provincial corporate elite.

Today, our very traditions of politics, our confined sense of what is possible, mitigate against the conceptual intuitions about democracy that guided the nineteenth-century Populists. Our problem in not understanding them, and the cultural issues raised by our inability to understand them, is not the fault either of the original Populists or of Jimmy Carter. Our problems are our own. They are rooted in our resignation about what is possible and what is not possible in the modern corporate state.

The Populists would not have admired their modern “progressive” descendants. Until we develop the cultural poise and self-respect to understand why, we will continue to think of politics as the special province of leaders. We will, therefore, continue to look to Washington and shape our response to harmonize with the requirements of what passes as modern political morale — with passive resignation, with sophisticated cynicism, or with romantic hope.

Such sundry modes of deference were not notable Populist attributes.

Tags

Lawrence Goodwyn

Professor of history at Duke University and author of Democratic Promise, the landmark history of the Populist movement. (1990)

Larry Goodwyn teaches history at Duke University. His son, Wade, born in Austin during the family’s years with the Texas Observer, is currently a member of the Longhorn Marching Band. (1979)