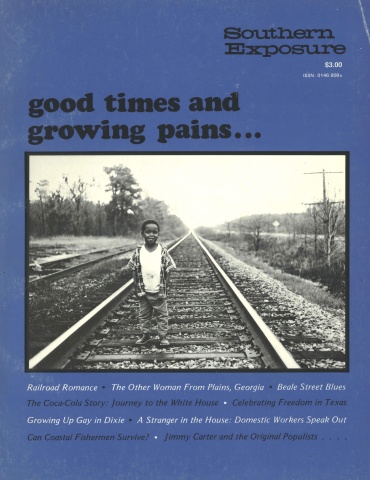

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 1 "Good Times and Growing Pains." Find more from that issue here.

Figuring out Jimmy Carter has become such an exciting and profitable pastime for writers and commentators that it may be too good to give up. Even when what he is becomes obvious, we’ll still keep watching his every move, ever more impressed by a finesse that has not been seen in Washington for many years. Jimmy Carter is a master illusionist, and even when his magic is known to be nothing more than a series of finely tuned techniques, the power to captivate our attention will remain, perhaps even intensify.

Many of us in the South were understandably amused by the success of Jimmy’s big act on the campaign trail. We gleefully watched him mesmerize the normally haughty national media and parlay the symbols of Southern provincialism into a national revival. But now that he has made it to the top, we feel a little duty-bound to admit that he’s not really just a good ole boy — especially since so many political analysts in the North persist in searching for the secret of Jimmy Carter in the South. In truth, the significance and skill of Jimmy Carter’s magic act goes far beyond the routines of Southern politics.

Southerners are quite familiar with the politician as magician. In fact, the South itself may rightly be seen as largely illusion: a place built on images, on the manipulation of symbols and the projection of order, beauty and unity onto what would otherwise appear as arbitrary, coercive and fragmented. It is no surprise that the South has nurtured its brightest minds into the nation’s most noted novelists, journalists, politicians and preachers. These are the trades that thrive in a culture rooted in myth and mystery, rhetoric and romance. Jimmy Carter is a hero in this culture.

What we have now is the Americanization of the Southern hero, or rather the Southernization of America’s identity crisis. For generations, Southern politicians have made it into office by promising their voters nothing more than self-respect. With an impressive repertoire of gimmicks and symbols (from galoshes and suspenders to Bibles and bicycles), they succeeded by making the mass of defeated, humiliated white Southerners believe in themselves, believe that they could survive, that they were better than those other people, that the South shall rise again! Southern politicians gave people pride, not prosperity, and for more than a century it worked.

Now an America shaken by the guilt of Vietnam, the shame of Richard Nixon, and the anxiety of economic crisis has turned to the modern Southerner for a few words of moral uplift. Jimmy Carter’s mission is to deliver us from evil with a government “as good as the people.” He promises to restore our national image, our belief in ourselves. Oh yes, Lord! We are a great country after all. Our righteousness will see us through the hard days. America shall rise again.

It’s a fantastic image, and with the proper orchestration it will continue to sell big. The trick, of course, is to package this image so well that it keeps selling even after it is recognized as rhetoric. The medium must become the message; the humble, gracious, open-minded, honest President is the government! Responsive politics is no longer a system that makes the state accountable to people, but a super-leader that citizens have access to. We believe that the government cares because Jimmy cares, and he’s okay because he says we’re okay. We are gently reminded that our real strengths as a nation are moral, not material, and our new feeling of superiority helps us forget who’s pushing the cost of energy up, or why we’re laid off, or what happened to national health insurance.

For this kind of finesse to be believable, very sophisticated image manipulation is required. Too sophisticated for the run-of-the-mill, good-ole-boy Southern “populist.” Jimmy Carter has succeeded so well — and will continue to do so — because he understands better than any previous President, including the facile JFK, that the power of magic in politics depends on mastering the techniques that control the audience’s attention. He has coupled his regional instincts for charm, sincerity and rhetoric with a keen appreciation for the technology that allows him to know and shape what it is people want to hear and feel.

There is no contradiction in this: the best magician is always the best technician. He knows exactly when to look you in the eye, when to tug his sleeve, when to introduce a new prop, with each movement designed to lull you into thinking things are happening that really aren’t. It is precisely Carter’s preoccupation with the mechanisms of political leadership that separates him from the intuitive, earthy Southern style of a Bible-quoting Sam Ervin or a sloganeering George Wallace. He is the master magician because he has adapted his skills as a technician, an engineer and a management specialist to the problem of Presidential power in an era when people are cynical about politics and Presidents. He manipulates his images for maximum appeal with information gained from systems analysis. No other Southerner ever did that.

In the campaign, the merger of image and technology was best represented by Pat Caddell, the Yankee computer-polling wizard. Everything from the green color-coding of the campaign literature to the inspirational tone of the Carter speeches was developed from detailed analysis of computer print-outs on the American voter. In fact, the process started in 1974 when Carter, as the Democratic Party’s National Campaign Coordinator for the mid-term election, gathered an elaborately detailed portrait of voters which revealed how hungry people were for symbols they could believe in again. With this knowledge, Carter began his act, dropping one image after another into the national media about who he really was: populist, outsider, non-racist, agrarian, management expert, fiscal conservative, born-again Christian. In the final days of the campaign, when Carter’s popularity in the polls was slipping, the creator of hundreds of Coca-Cola commercials, Tony Schwartz, was brought in to help. The voters were beginning to wonder if the moralist farmer they liked could be a respectable president; so the man who worked on making Coke “the real thing” repackaged Carter as the serious, subdued candidate. “We took him out of the fields and put him in a suit in a library,” says Schwartz about the new TV ads. “Whether it’s Coca-Cola or Jimmy Carter, what we appeal to in the consumer or voter is an attitude. We don’t try to convey a point of view, but a montage of images and sounds that leaves the viewer with a positive attitude toward the product regardless of his perspective.” This final touch by Coke’s brilliant media technician put Carter over the top and foreshadowed things to come.

Once in the White House, the Carter show took on dazzling dimensions. It’s not just that he continues working the symbols to keep his own popularity high. He literally intends to transform the image and technique of government administration so that it becomes both more acceptable to the general population and more efficient in serving America’s economic interests in a new era of global competition. To accomplish such an ambitious goal, Carter first brought in a team of management wizards who had the vision, administrative skills, and muted arrogance to reorder America’s system of government. The merger of image and technique which these managers relish is perhaps best illustrated by the members of the Carter team selected from two of the world’s largest multinational corporations, Coca-Cola and IBM (including Coke-retained attorneys and executives Griffin Bell, Joseph Califano, Charles Kirbo, Charles Duncan and J. Paul Austin, and IBM directors Harold Brown, Patricia Harris and Cyrus Vance).

No other organizations have succeeded so well in perfecting the technique of packaging their products with an irresistible mystique. Coca-Cola has done it by literally transforming what is essentially colored sugar water into an all-purpose elixir indispensable to life itself. It is the world’s quintessential manipulator of images—and it is run by Southerners. IBM has done it by making technological innovations indispensable to the business world’s capacity to expand. It is the quintessential manipulator of information, the basis of modern organizational planning and power.

Behind the images of these clean companies faithfully serving their constituents lie nothing less than the most sophisticated, shrewd and farsighted corporate managers in the world. Like Carter, they are fundamentally technicians, the master manipulators of image and information; they deal in goals and management-by- objective, not antiquated ideologies that can be labeled “conservative” or “liberal.” Like Carter, they are specialists in reorganizing bureaucracies to maximize their efficiency in solving problems. Their two interrelated goals are simply to restore public confidence in a faltering domestic political economy and to bolster the position of the dollar—the ultimate expression of America-in an expanding system of international trade. The first requires opening the government to outsiders with everything from walk-in voter registration to phone-in talk shows; and in doing that Carter appears the liberal. The second involves controlling inflation with everything from cutting pork-barrel spending to opposing labor’s minimum wage; and in doing that Carter appears the conservative.

In fact, both programs are part of a style of politics as new to the South as to Washington. It is a style that unites magic and technology, image and information, a style that is more fascinated with the mechanism of efficient administration for reaching measurable objectives than with balancing off the special interests and their lobbyists.

Meanwhile, by playing the country boy from Plains, Jimmy endears himself to the voters and keeps the attention of the media focused on his Southern roots. Of course, we don’t mind a little attention down here now and again, but we know our quaint ways can sometimes distract people from the bigger issues. Behind the sleight-of-hand tricks, Jimmy’s main act has more to do with the introduction of corporate gamesmanship and computer technology into Presidential politics than with bringing work shirts and black-eyed peas into the White House; it is the dramatic distortion of democracy, not its fulfillment.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.