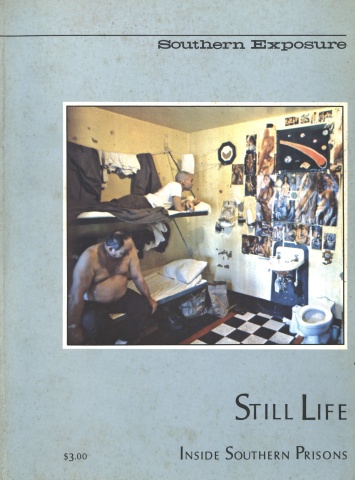

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 4, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons." Find more from that issue here.

Florida State Prison: Gary Gilmore, who was so insistent on his execution, and who was obliged by the State of Utah 14 months ago, was the kind of man the public fears and thinks archetypal of murderers: cold-blooded, pitiless, cynical to the core.

But the true test of capital punishment, and the public support of it, lies in the execution of a man who does not want to die. There has not been such an execution in this country in 11 years.

One is now looming at this prison in the spare, flat, green countryside of north central Florida. If it comes to pass, as it may this winter, it will take place on the ground floor of this prison, in a three-legged chair hand-built by prison inmates many years ago, in full view of reporters from the print and electronic news media.

It is in keeping with state sentiment and court practice that the next execution should take place here. The Florida legislature rushed into special session to enact a new capital punishment law when the US Supreme Court struck down the old one in 1972. As of late September, 1978, there are 118 men and one woman on Death Row in Florida, more than in any other state.

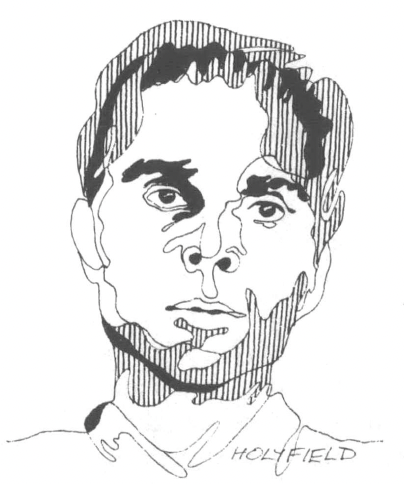

The first one scheduled to die is a brown-eyed, handsome man, white, 29 years old, an admitted killer of a fellow prison escapee named Joseph Szymankiewicz.

John Arthur Spenkelink was raised in Buena Vista, California, where his mother was a teacher and his father something of a failure and a drunk. Fie established a criminal record there and was extradited after killing Szymankiewicz in a motel room in Tallahassee in February, 1973.

The record began with his first arrest at the age of 12 for fighting, malicious mischief and burglary. It is a record of offenses that grew steadily every year thereafter through charges of battery, running away, burglary, auto theft, narcotics — the classical range of adolescent crimes.

It expanded, when he was 19, into several charges of armed robbery. He had spent time in juvenile institutions, but conviction on the new charges sent him into the California prison system on a sentence of five years to life. He did time in San Quentin, perhaps the toughest of American prisons, where the relationship between black and white and Puerto Rican had settled into fear and hate. There he learned about survival in a racial guerilla war, learned it painfully once when he was stabbed in the back with an icepick while walking up some stairs.

Moved to a lighter security institution, he escaped — “just a walkaway,” he says — and hooked up with the older Szymankiewicz, an escaped career criminal whom he picked up hitchhiking on a Texas road. They stayed drunk a great deal, and for the promise of money, he says, Spenkelink drove Szymankiewicz to New York, then Baltimore, then Detroit, and finally to Tallahassee. In Tallahassee, Spenkelink says, Szymankiewicz robbed him. And then there was the motel room murder, or as Spenkelink swears, the self-defense shooting. At the age of 23, Spenkelink shut the motel room door and took to the road again. He ended up in a rental apartment in California; there he was found and arrested. He pleaded guilty to two more armed robberies before being extradited back to Florida to stand trial for murder.

At the trial in Tallahassee, he took the stand to say that the gun belonged to Szymankiewicz, who had once used it to force Spenkelink into a homosexual act. When Spenkelink tried to get his things and leave, Szymankiewicz began to choke him and then went for the gun. In the struggle, Spenkelink shot Szymankiewicz once. Past that point, he said, his memory went blank. Szymankiewicz was found in bed, shot twice from behind and clubbed on the head. The jury found Spenkelink guilty of murder in the first degree, and the judge sentenced him to death.

That was the record which was in part responsible for moving Governor Reubin Askew to select John Spenkelink to be the first to die under the state’s new capital punishment law, which had been tested and found constitutional by the US Supreme Court. He signed the death warrant on September 12, 1977.

Askew has never agreed to speak about the reasons which moved him to choose Spenkelink to die, but there are others besides his criminal record. There were six men whose death warrants Askew was legally free to sign once a State Supreme Court stay expired the last of August. But Spenkelink was the only one with no attorney and no appeal of any kind filed in court.

He took the news in character. He is an inch over six feet tall, lean, muscular, soft-voiced, cautious in conversation and unfailingly polite. He keeps an immaculate cell and person, writes a small, scripted, precise longhand and is determinedly self-reliant, something he has perhaps learned in the time he has spent in the treacherous society of prison. Perhaps because of the length of that experience, he is not well-educated. He does not really understand the various functions and responsibilities of the judicial system, the executive and the press. But he has his standards.

He once told me that in California, “I pleaded guilty to three first-degree armed robbery charges so three other dudes could get off. That’s the way I’ve been raised. It doesn’t do any good for anybody to do any more time than necessary.” When a Christmas card circulated on Death Row in 1976, collecting signatures to be sent to Florida Attorney General Robert Shevin under the message “Wish You Were Here,” Spenkelink declined to sign. Shevin, who argues against their appeals and for their execution, is the nemesis of the residents of the Row. But the card offended something in Spenkelink.

And when the massive, mustachioed prison superintendent, David Brierton, called Spenkelink down to the office on that Monday a year ago to tell him that Reubin Askew had signed his death warrant, Spenkelink thanked him for the courtesy. That’s all.

Then they led him down to a newly painted, sunny yellow cell on the bottom floor of Q Wing, down the hall from the room where the Electric Chair is bolted down to the floor. There Spenkelink waited, alone but under constant guard. For two weeks, while Florida attorneys Tobias Simon and Andrew Graham consulted with lawyers at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in New York and rebounded from court to court in search of a stay, he waited. He got within two days of the date set for his execution before his lawyers secured a federal stay while they appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans.

Governor Askew said he would not sign another death warrant, for Spenkelink or any other person on Death Row, until Spenkelink had exhausted his last appeal. Spenkenlink’s attorneys filed some 19 issues of argument with the Fifth Circuit, but there was one primary issue: that capital punishment in the state of Florida was still being imposed unequally by the courts because 95 percent of all those on Death Row were there because they had killed a white. The life of a black man, in other words, had yet to achieve an equal worth. It was an intriguing argument, and Florida Attorney General Shevin, then and now the front-runner in the race for Governor, argued personally and strenuously against it.

“Ridiculous,” he said.

On Monday, August 21, after 10 months of consideration, a three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit rejected all the arguments of the defense in a 40- page long opinion.

Shevin, when he heard the news, was jubilant. Spenkelink, when I saw him the next day, was calm. Legally, he is far closer to execution than anyone else in the United States. There is only the US Supreme Court left in this current appeal. “It’s just not going to bother me,” he said. “In order for me to function right every day, I just gotta keep a cool head.”

“I’m not blocking reality,” he said. “It’s right there on Front Street all the time. I’m afraid of the chair, too, but... I’ll handle anything they dish out. I’ve done programmed myself to handle that, no matter what.”

Tags

Dudley Clendinen

Dudley Clendinen is a roving columnist for the St. Petersburg, Fla., Times. He is currently at work on a book about Florida’s death row, to be published by W. W. Norton and Company. (1978)