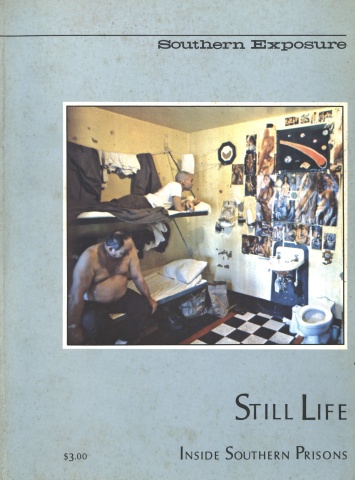

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 4, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons." Find more from that issue here.

Johnny Harris walks into the window-encased visiting room of Holman prison, Alabama’s maximum security facility. He is a strong-looking man about six-one, 175 pounds and wears blue jeans, a dark blue polo shirt, light-weight jacket and tennis shoes. His hands are cuffed but he is smiling. “He’s always smiling,” a guard standing nearby says. “If I was in his shoes nothing would ever crack my face ... I’d be just like stone.”

The 33-year-old black inmate greets his attorney with a hard handshake and stares into his eyes. They sit down together on a church-like wooden bench and talk about how things are going.

“My blanket got here just in time,” Harris says, referring to a blanket his lawyer’s wife sent him. “It was getting cold. Sometimes the guards on the night shift turn the heat off on segregation ... the water too.” Harris cracks a laugh. “Just depends on how they feel. Guys in population don’t have that problem.

“That judge couldn’t have considered all the evidence in my case,” Harris says about his last appeal. “He only took two weeks to make a decision.” Then he asks, looking down at the floor: “What we gonna do now?”

Johnny Harris faces a death sentence for his involvement in the January 18, 1974, inmate rebellion at Alabama’s Fountain Correctional Center, in which a white prison guard was killed. His story is similar to that of hundreds of other inmates incarcerated in American prisons and facing the death penalty. Many share a common bond: because they are poor they cannot afford to buy quality legal representation, which is many times the only factor determining whether a defendant will live or die. They simply cannot afford the high price of justice.

Harris began his life in the heart of the Black Belt region, near York, Alabama, a small rural community located about halfway up the state just a few miles from the Mississippi line. His mother and father managed to squeeze out an existence by taking on odd jobs for the local white population, and, though poor, they managed to get along well in the rural community. But Johnny’s life changed abruptly when his mother died and his father was killed on a construction job where he was working. It was then that Harris moved to Birmingham to stay with his aunt and uncle.

Away from the secure and stable rural life that he had known, Harris had trouble making it in this highly competitive, industrialized deep South city; it was the early 1960s when racial tension was approaching its breakpoint. He was in and out of school for a while and then finally dropped out to search for work before reaching the ninth grade. He found nothing steady, and in 1962, at the age of 16, he was arrested and charged with two counts of Second Degree Burglary — one for stealing shoes, the other for stealing a small amount of cash. He was tried and convicted as an adult in Jefferson County and sentenced to four years in prison for two petty crimes that more affluent teenagers would have probably gotten off with no more than a caution from police and a slap on the hands from their parents. Harris would later be sentenced to an additional three years for an attempted escape. By the time he was released — seven years later, in 1969 — he had served his full sentence.

Behind bars for the first time, Harris was exposed to a system in which, according to court reports, there was no effort on the part of the state to separate violent from non-violent prisoners, youthful and impressionable offenders from older, habitual criminals — where the young were often raped and then sold as prostitutes to the highest bidder. These were the same conditions that eventually led to the 1974 rebellion at Fountain Corrections Center, and that in 1976 would prompt Federal District Judge Frank M. Johnson of Montgomery to take control of Alabama’s prisons, describing them as “barbaric and inhumane” and so overcrowded that they created a “jungle atmosphere.”

“It was simple to accept it,” Harris recalls of his first confinement in prison. “I mean, I wasn’t going anywhere . . . and surviving is the best incentive for learning to live with it.”

Out of prison in 1969, he was again faced with poverty and this time the odds were slimmer than ever that he could make it on the “outside.” He now had a criminal record which would weigh heavily against his attempts to find work and begin a new life. But he married a childhood friend, moved into her family’s home, and found a succession of temporary jobs — as a janitor in a bus station, a laborer in a steel fabrications plant, and a laborer for an industry producing target ammunition for the military. For the first time, Harris began to feel that things were turning around for him. It was a feeling that was enhanced with the birth of his first child about a year after his release.

In March of 1970, Harris and his family decided to move from then crowded apartment to the Ensley area of Birmingham, giving little thought to the fact that the neighborhood they had chosen to settle in was predominately white. White residents, however, were outraged to have blacks moving into their community; fearing that to allow one black family to stay would lead to an influx of others, many of the whites launched a concerted effort to drive Harris and his family out.

One white woman who had befriended them stated that they were subjected to constant racial harassment and abuse. It got to the point, she said, that the local Ku Klux Klan members would hold meetings in the neighborhood Baptist Church to discuss ways of making them move. Some whites, she said, even went so far as to try to persuade neighborhood kids to firebomb and vandalize Harris’ home and property. The woman herself was later the victim of vandalism and harassment from many of her neighbors because of her efforts to make Harris and his family welcome in the neighborhood.

For months Harris and his family withstood the abuse and harassment, believing that eventually the white folks would come to accept them or at least overlook their presence. Then on August 11, 1970, as Harris was riding to work with his wife’s parents, the police stopped the car and picked up Harris and his wife’s father. The Birmingham police had a well-known sympathy for the Klan, so Harris had cause for concern. The questioning was all routine, the policemen assured him, but Harris soon learned otherwise.

Though no warrants for their arrest had been issued, they were taken to the Jefferson County Jail, fingerprinted, and placed in a line-up. After the line-up, Harris learned that he had been identified as a rapist by an eighteen-year-old white woman. Unable to believe what he was hearing, Harris told the detective where he had been on the night of the alleged rape, but his alibi was rejected and he was repeatedly pressured to sign a statement admitting to the rape. When he refused, Harris was thrown in jail. His present attorneys say that the woman’s original description of her attacker came nowhere close to resembling Harris. The following day he was charged with four counts of robbery involving money in the amount of $11, $67, $90 and $205, stolen from a service station and a drive-in theater.

Harris sat in jail for eight months between August 12, 1970, when he was actually charged with the crimes, and April 6, 1971, when he was sentenced to five life terms. During this period the court appointed three attorneys to defend him. The first one waived Harris’ right to a preliminary hearing; none of the three lawyers ever filed a bond motion on his behalf, nor did they do much to ensure that Harris had an adequate defense when he went to trial. One attorney did interview alibi witnesses, finding several who were willing to swear that Harris was somewhere else at the time the rape occurred; but none of those witnesses were ever subpoenaed to appear in court. One attorney even showed his apparent lack of concern for Harris by having himself subpoenaed to appear in court for the trial. He did it, he said, to make sure he would remember to be there.

So on April 6, 1971, Johnny Harris appeared in court to face the death penalty with virtually no defense at all. Each of Harris’ charges carried the maximum penalty of death; the district attorney offered to reduce these to life imprisonment if Harris would plead guilty. Just before the jury was brought in and the trial was to begin, he recalls one of his attorneys “told me he didn’t see how he was going to win the case when the court was going to take the white woman’s word over mine because I was black, and he didn’t have no intention of bucking the system. The he advised me to go ahead and take the D.A.’s offer because if I didn’t I would otherwise get the chair.”

Harris’ “deal” was that if he would plead guilty to the rape charge, then the four robbery charges would be dropped. He refused and told his attorneys that he wanted to take the stand and give his testimony.

The court proceeding went on, but following qualification of the jury Harris had a talk with his other attorney, who also tried to persuade him to take the deal. Harris said he was told then for the first time that no alibi witnesses had been subpoenaed, and the attorney told him bluntly that he wasn’t prepared to go to trial.

Though adamant about his innocence, Harris realized then that he had little choice: it was either the death penalty or one life term for the rape. “I changed the plea on the rape case in order to get the other four dismissed and to get around the death penalty ... I had proper representation to worry about and I didn’t have it,” he said.

Harris was sentenced that same day to five life terms. The four robberies were not dropped. Apparently, five “papers” he signed for his “deal” were admissions of guilt for each crime. He remembers signing only one paper.

Harris lost everything in his life when he was sentenced in Birmingham that day and denied the right to prove his innocence because of ineffective representation by his attorneys. His family, under the pressure of continued harassment and worried that what happened to him might also happen to another member of the family, finally moved from the white neighborhood a few months after Harris was arrested. But worst of all, he lost contact with his wife and baby in December, 1970. He has not heard from them since nor does he know what became of them. It is a subject he does not like to talk about and he gives little response when asked why.

He recalls that period of his life: “For me it was a time of craziness and frustration like you wouldn’t believe. But I ain’t bitter ... I mean who am I supposed to be bitter against?”

Harris entered prison for the second time with little hope of ever getting out. But he was wiser this time around and with nothing left to lose, he began working with other inmates for improved conditions in Alabama’s prisons — especially the two Atmore facilities, Holman maximum security prison and Fountain Correctional Center, where he was serving his time.

He adopted the name Imani and joined a prison activist organization consisting of both black and white members who were determined to see that the people of Alabama and the lawmakers became aware of the deteriorating conditions in the state’s prisons. The organization was called Inmates for Action and, among other things, taught basic education to inmates who could neither read nor write. Many IFA members were outspoken and considered by the Alabama Board of Corrections to be militant radicals determined to undermine the prison officials’ authoritative hold over inmates. But Harris wasn’t considered to be one of the radicals. As one guard said: “Harris was mostly quiet. He was one of them, but he didn’t cause no trouble.” And despite pressure from IFA members to take stronger stands and become more outspoken against the system, Harris’ involvement with the IFA remained relatively low-key.

The conditions alone at Fountain were bad enough to strain the patience of most inmates, but when prison officials stepped up their efforts to break up the IFA, the increased pressure and harassment finally reached breakpoint on the afternoon of January 18, 1974.

IFA members in segregation units 1 and 2 at Fountain received word that another IFA member at Holman, located just two miles from Fountain, had been beaten and possibly killed by prison guards there. According to accounts of the witnesses, Harris was one of two inmates ordered by IFA leader George Dobbins to take two guards hostage. Harris and another inmate, Oscar Johnson, were “cell flunkies,” or cellblock trustees, who had access to the control lobby at the front of the segregation cellblock where two guards were stationed. When Harris and Johnson returned food trays to the lobby that afternoon, they jumped the two guards and took them hostage.

After Dobbins was released from his cell he made several demands of prison officials, but none were ever met. Then later that afternoon, Fountain’s warden, Marion Harding, led his riot squad into the cellblock. What followed was a short but bloody confrontation which left one of the hostages, Luell W. Barrow, dead from stab wounds and a number of other guards and inmates suffering from injuries. Dobbins was also injured, reportedly from a gunshot wound, and he was found kneeling over the body of Barrow with a knife in his hand. Later Dobbins died, but according to an autopsy report, not from a gunshot wound, but stab wounds to the head and face — wounds Dobbins received either immediately following the riot or while en route to a Mobile, Alabama, hospital. Although the Alabama Attorney General’s office has investigated Dobbins’ death to some degree, no attempt has been made to prosecute anyone in connection with it.

Harris was indicted on April 2, 1974, along with four other inmates, for Barrow’s murder, despite the fact that he was never implicated in the murder during the state’s first investigation. The Attorney General’s office discovered that Harris was serving life, and Attorney General Bill Baxley made the decision to prosecute him personally under the only death penalty statute on the books in Alabama at the time: an 1862 statute, Title 14, Section 319, which calls for the death of any inmate convicted of first degree murder while serving a life sentence.

He watched the year between the time he was indicted and finally went to trial go by in a flurry of motions and hearings that, at one point, saw him subjected to the worst kind of racial discrimination: he was called a “nigger” in a courtroom hearing by the presiding judge, who later claimed he said “nigra” and not “nigger.” The judge followed his statement with another blunder, declaring that despite what he said it should not be taken seriously because he was only joking when he said it. Not long after the incident occurred, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals ordered the judge to recuse himself from the case.

When Harris went to trial on February 24, 1975, in the Baldwin County Court House of Bay Minette, Alabama, one reporter stated that the trial would be nothing more than a rehearsal for Attorney General Baxley’s campaign to re-establish the death penalty in Alabama. Baxley knew that a conviction, even under the rarely used Section 319, would prove to be instrumental in the passage of a new Alabama death penalty law which he had written. Baxley’s law was passed in 1975 and by mid-1978 had resulted in the addition of 36 more inmates to Death Row.

Baxley and the State of Alabama failed to provide enough evidence during the trial to prove Harris was involved in Barrow’s stabbing. Though he was on trial for his life and charged with first degree murder, incredibly the state never contended that he killed Barrow. In a pretrial hearing, Assistant Attorney General George Van Tassell told the court: “It is not our position that the defendant was actually holding the knife or anything else. We don’t contend that this defendant stabbed the guard.” What the state did contend was that Johnny Harris could still be convicted under Section 319 as an accessory to murder because he took part in the rebellion. At the same time, the state chose not to prosecute a number of other inmates who were also involved in the rebellion.

Despite the lack of substantial evidence linking Harris to Barrow’s murder, on February 28, after a four-day trial which took place under heavy security, Harris was convicted by an all-white, all-male, all-over-40-years-old jury and sentenced to die in the electric chair by presiding Judge Leigh Clark of Birmingham.

Following his conviction, Harris became more outspoken about the type of criminal justice system which he felt had unfairly and discriminatingly brought him to trial to face the death penalty for the second time in his life. He called it “a system that robs poor people of their very existence by leaving them little room to fight for their freedom.”

He took to calling himself “Baxley’s political scapegoat,” saying that the attorney general’s personal prosecution of his case was being used by Baxley as a catalyst to further his political career. And indeed Baxley used the Harris case and his death penalty law as examples of his tough stand on law and order to woo voters in his bid to replace George Wallace.

Harris’ new attorneys, Clint Brown and Diana Hicks of Mobile and William Allison of Louisville, Kentucky, are now challenging his 1971 sentences on the grounds of ineffective representation as well as continuing to fight for a new trial over his 1975 conviction and death sentence.

In the meantime, Harris spends his time in a small cell on Death Row at Holman Prison. What he thinks of now is not what happened to him in Birmingham or what it’s like to face death in the electric chair, but what he must confront everyday in a system which erodes a man’s dignity and self-worth. Somehow he continues to exude a quiet calm and inner control from which springs an optimism and hope that leaves those who know him, or who come in contact with him, wondering how he does it.

Recently, the story of Johnny Harris has become a celebrated case — at least in the Soviet Union. Few people outside Alabama had ever heard of Harris until the Soviets, in retaliation for President Carter’s attacks on their own human rights violations, began promoting Harris as a political prisoner of the United States and a victim of a racist and inequitable judicial system. Since the Soviet Union’s “Free Johnny Harris” campaign started in early 1978, the American press has begun reporting on his case. But too often the accounts have accepted as fact the portrayal of Johnny Harris as a rapist, robber and murderer.

Tags

Greg McDonald

Greg McDonald is a free-lance journalist who has been following the Harris case for the past three years. He was a member of the team which worked on the federal court-ordered Alabama Prison Classification Project of 1976, and has written numerous articles on the state’s prisons. (1978)