This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 3 No. 4, "Facing South." Find more from that issue here.

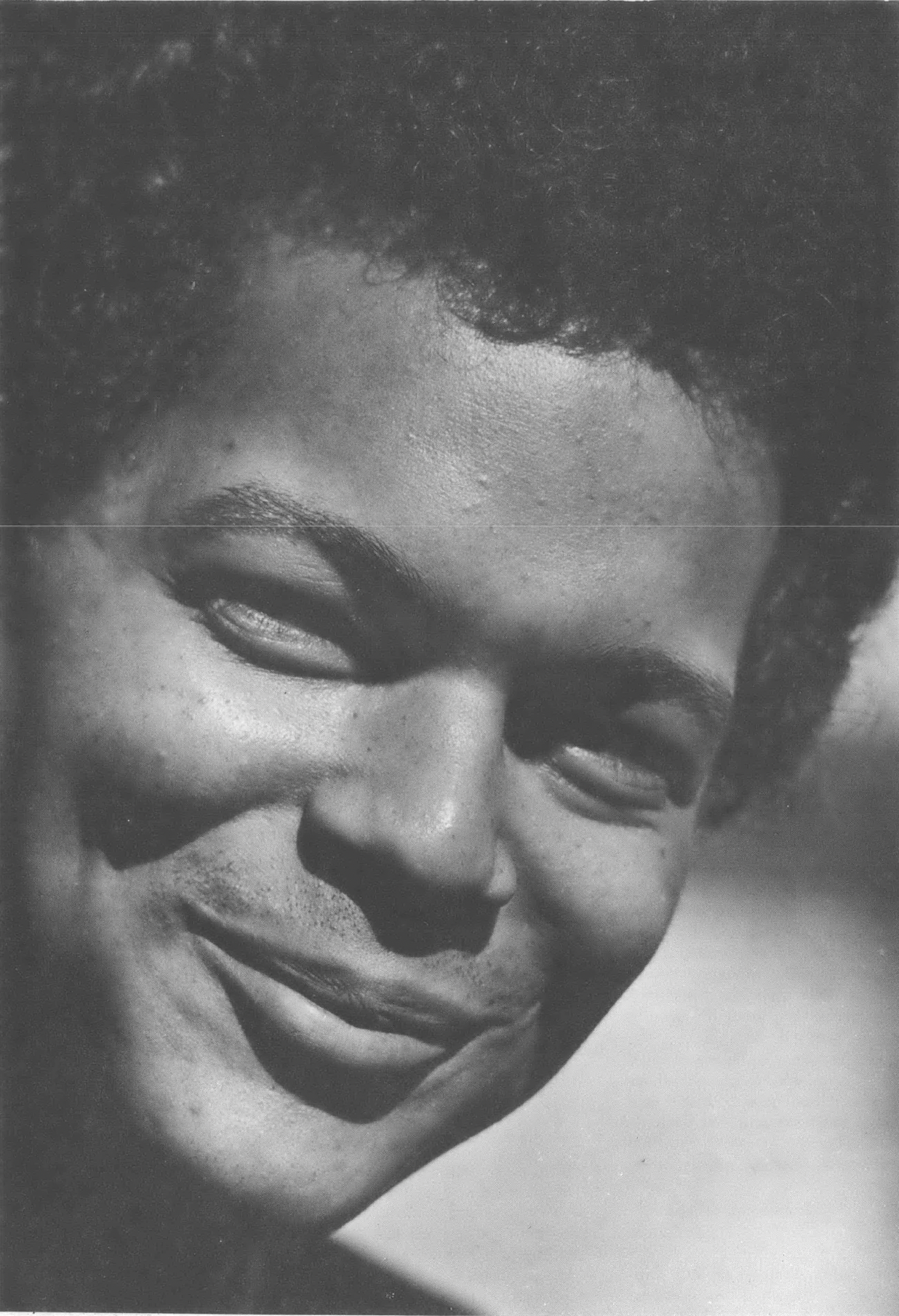

Julian Bond possesses a blend of poise and easy humor that is often associated with distinguished families who have assumed the responsibilities of community leadership. His father, Dr. Horace Mann Bond, was an astute historian of the black experience, and though he rarely received just recognition from white scholars, his studies are now praised as classics in the field. Julian was headed for a career as an intellectual leader himself, perhaps as a creative writer, when the storm of the civil rights movement swept him into political life.

Bond was 20 in 1960, when four students sat-in at the Woolworths lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., and triggered the mass entrance of black students into the movement. A few months later, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was formed, and Bond began directing the organization’s publicity work. In 1965, he gained national notoriety when the Georgia state house of representatives refused to let him take his newly-won seat in the assembly. The white majority claimed his endorsement of SNCC’s anti-Vietnam statement amounted to a rejection of the US Constitution, but in the resulting legal battle, the US Supreme Court finally upheld Bond’s right to political office.

Bond now serves in the state senate and nationally is one of the strongest advocates of black political power. He has even announced that he would run for the Presidency himself, if he could finance a campaign. Today, he regularly speaks to twenty different groups in a month, as a means both to support his wife and five children and to get his message out to a wider audience. Although the news media rarely gives his serious views full treatment, he consistently projects a radical alternative for America’s economic and political organization. At the same time, and with typical nonchalance, he maintains a wry sense of humor, finding it hard, as he says, “to resist the opportunity for a little witticism when folks are feeling overly self-important. ”

This edited interview of Julian Bond’s thoughts on the movement’s development since the early 1960s was conducted in Atlanta in December, 1975, by Bob Hall and Sue Thrasher.

Question: Let’s start at the beginning. I’m interested in what you learned as a child from your father and others that had a bearing on your own development as a leader, what was passed from one generation of black leadership to another?

Julian Bond: Well, it was less my father or other people saying, “Here’s what you’ve got to do,” than learning from the examples they set. For instance, I saw the way my father responded to pressures which came down on him-and in one case nearly crushed him. That was when he was president of Lincoln University in Lincoln, Pennsylvania, which was then a private black college, the oldest in the country, as a matter of fact. Anyway, the board of trustees decided they wanted to integrate the school. It had always had a few white students, just like any other black college, but they wanted to integrate even further. My father resisted that, and lost his job and had to come down to Atlanta and be dean of the School of Education at Atlanta University.

At the same time, a stream of people were in and out of our house, and we had a chance to watch them. I have a picture of myself and Dr. W.E.B. Dubois and E. Franklin Frazier —I was just four years old—and it has the three of us in academic regalia. It was a half-serious, half-joking plot of my father’s to consign me to a life of academic study.

And then there was Paul Robeson, who was somebody to emulate, you know, he is somebody who had a certain kind of life that is worth copying. And I saw Walter White, who was then the executive secretary of the NAACP, and learned that here is somebody who is in fact a professional civil rights worker, one of maybe 20 in the country. You see, at that time there was no “class” of people who were professional civil rights workers. Today there is, both from public and private life, if you call the affirmative action director of IBM a certain kind of civil rights worker —probably not very much of one. But in the early 1940s, this wasn’t the case. There was, however, a very strong sense that the educated black person had a responsibility of sharing his training and skills with others, with those less fortunate. If you were a scholar, you had a responsibility to study the black condition — as my father and Dr. Dubois did. If you were a doctor, it was more than just treating sick people, but having concern for the race as a class, as a group.

Then, again, I was raised in a home that was full of books about Africa and the South and Black America, and those were topics of conversation all the time. And it was a home full of black newspapers, the Pittsburgh Courier and the Afro-American, as well as the New York Times and so forth. I remember my impression of the South when we moved to Atlanta from Lincoln in 1957 was formed largely by those black newspapers which at the time were often sensationalist. Whenever anything particularly vicious took place in the South it was front page news in the black press for weeks. I can remember one incident of a guy who was a Korean veteran being beaten blind in a bus station in some Virginia or North Carolina city. And I thought those kinds of things happened daily, and that you were literally taking your life in your hands to walk into downtown Atlanta.

But, on the other hand, it was only when I went to Atlanta that I discovered for the first time that this group of black doctors and lawyers and writers and, really, largely academic types, had a national character to it—a whole community of people separated by professions. So when I entered Morehouse [part of the Atlanta University complex] I found that I would know people because if your father teaches at Tuskegee and somebody else’s father taught at Fisk and somebody else’s at Albany State, then you all knew each other.

Southern Exposure: But part of recognizing that you belonged to this middle-class, professional network was the realization that others didn’t belong to it?

Bond: Oh, yes, very much so. I’ll tell you one thing that shocked me. When I came to Morehouse, I had a great facility for testing. I had taken the college boards twice, and I bet that I scored higher on the college boards and entrance tests than any other freshman at Morehouse. But by the end of the year, I had come down to about the middle third of the class. What had happened was that these young men - some of them early admission students, 15 and 16 years old, who had interrupted their high school education to pick cotton or peaches, and for whom education was the most precious thing in the world —these guys would study all night, after coming back from work somewhere as waiters, sleep for an hour, go to class, go back to work. They were not your classic grind, but were well rounded people, very attractive and very much interested in upward mobility.

Southern Exposure: When the civil rights movement started, which class background did the student leaders come from?

Bond: Well, I’m not sure. The person who involved me in the movement was Lonnie King, who had entered Morehouse from high school, was not from middle-class origins at all, had left Morehouse and gone into the Navy, and had come back to be older than the average student-but was very much the big man on campus, a football hero. We were just running out of Korean veterans —this was 1959. Then there was Ben Brown, whose father had been an embalmer and had a job then working as a laborer. Charlie Jones’ mother was a professor at Johnson C. Smith and had a Ph.D., and Charles Sherrod was a student at Virginia Union and I think was raised by a mother who was a maid. Even if they came from exact opposite backgrounds, they were all in college. They all had entered the middle class. College at that time was almost a guarantor of a job, and it was a tremendous step toward upward mobility.

Southern Exposure: So the college students were enough inside the middle-class values, the aspirations of what America should give them, to see the contradictions, the limitations, as unjust?

Bond: Well, many people saw them earlier. Take John Lewis, for example. He saw them when he was in high school. John was riding a bus into Montgomery from Troy —quite a distance—to go to the mass meetings when the boycott started in 1955. He went to see Rev. Shuttlesworth and Dr. King in Montgomery to get their help so he could file suit to integrate the schools in Pike County, and I think they discouraged him because they thought he’d be killed. So some of these people were active in their high school NAACPs, and when they got to college, they were almost in place holding, and they probably didn’t know they were waiting, but they were poised and ready to jump in.

When the Greensboro sit-ins happened in early 1960, that was it. It wasn’t that much of a conscious decision of what to do. Greensboro became the model, almost a blueprint. You didn’t say, “Why did they go to Woolworths?” You thought, “Gee, we got one right here.” And you didn’t say, “Why were they nonviolent?” There was no choice; they would have been killed, or beaten severely, so that was the best thing to do. It also put pressure on the white community, you know. You held up a standard of decency and goodness and honesty, and your opponents were so obviously evil. The moral aspect, of course, was very strong because so many of these people were pre-ministerial students — Sherrod, Charlie Jones, John Lewis and on and on.

Southern Exposure: How did the news from Greensboro come to Atlanta? What did the Atlanta University students do?

Bond: I was sitting in the Yates and Milton Drugstore on February 3, 1960, and Lonnie King, who I only knew as a football hero, a “big man on campus,” came up to me with this Atlanta Daily World that said something like “Greensboro Students Sit In for Third Day.” And he said, “What do you think of this?” And I said, “Well, I’ve read about it.” And he said, “Don’t you think somebody ought to do it here?” And I said, “Well, somebody probably will.” And he said, “Let’s us do it.” And I wanted to say, “What do you mean, us?” You know, “Why me?” He said, “You take this side of the drugstore, and I’ll take the other, and get everybody here to come to a meeting at noon.” And we did it, and that’s how it began.

We formed a committee and went to see the presidents of the Atlanta University colleges, and particularly Dr. Clements, the AU president, who told us that the AU Center had always been different from all other black schools in the country and that it wasn’t sufficient just for us to sit-in. I think they were trying to buy some time. They said no one will understand what you are doing. Of course people would understand, but we said, “Yes, you’re right, no one will understand why we are sitting-in.” So they encouraged us to issue a statement of principles, and we did. The students wrote it, and called it an Appeal for Human Rights, and it listed a dozen or more things that we thought were wrong. We got the money —with the help of some adults —to put the Appeal in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution with the signatures of the student body presidents of the AU schools, and it concluded by saying, “We pledge our hearts and minds to do whatever is necessary” — which were strong words then-“to see that these rights are granted us.” Of course, that caused quite a little storm. I remember that Gov. Carl Sanders said the thing sounded like it was written in Moscow, if not Peking. But, you know, Atlanta had this concept of itself as a “City Too Busy to Hate.” and Mayor Hartsfield, who coined that phrase, said, “Of course this is not written in Moscow or Peking; this was written by our own students whose demands are entirely legitimate.” This was before any action at all.

The following week, Lonnie King and myself and another person went downtown to survey our lunch counters. We really made the store people nervous with our yellow pads and pencils, saying things like, “Let’s see, there are 15 people at this counter.” The store detectives would just about faint; they knew something was happening.

On March 15, 1960, we went to every dime store in town, to the bus station and to the cafeterias at the federal building, the state capital and the city hall. We purposely picked three different kinds of targets. I was the leader of the group that went to the city hall cafeteria. And it had a big sign outside saying “City Hall Cafeteria: Public Is Welcome,” apparently because there wasn’t enough business just in city hall. But that only meant whites, not even black city employees. Well, we went in, and the woman in charge called the police —it was all pretty straight-forward, not as vicious as in other cities at the time—and they packed us in the paddy wagon and took us to the old jail. I had told the group we would be in jail only an hour, but the hours ticked by, and they began saying, “What’s happening, Bond? You told us we would only be in here an hour. I’ve got a class this afternoon.” It wasn’t until six that evening that we got everybody out. I remember we all went to Paschal’s for dinner. It was a real celebration. Of course, it was a surprise to most the community, including Dr. Clements, who we thought was trying to slow us down. We had some adults helping us; they bonded us out, and later, when the grand jury indicted us on charges of conspiracy and restraint of trade, with possible maximum sentences of something like 99 years, the adults worked out a deal and kept getting the trial delayed indefinitely. But it was mostly just us students in this Committee on Appeal for Human Rights.

We decided next to engage in hit-and-run sit-ins, to sit-in a place until just before the police came and leave and not be arrested. The stores then began to adopt a policy of closing down the lunch counters periodically. Well, we finally stopped messing around with these Woolworths and Grants and so on. They were taking their orders from New York, and while there were people picketing Woolworths in probably a hundred southern cities, we felt we weren’t going to change much by focusing on them in Atlanta. It was out of our hands. So we decided to go after the giant in Atlanta, which was Rich’s; it was the largest department store in the city and it was locally owned. Everybody went the way Rich’s went, and we found out very early that Rich’s was vulnerable. We had had a meeting with Richard Rich down at the police station—Police Chief Jenkins, Lonnie King, Richard Rich, myself, and probably Mary Ann Smith or Hershel Sullivan. And Rich tried to tell us, “Why y’all picking on me? I give $500 every year to the United Negro College Fund.” He was very worried, and we knew we had him, so we kept pushing him and pushing him.

We put up a picket line around his store—which was right downtown where all the buses came—and started collecting credit cards from the community and started boycotting him. His trade just went down, down, down. You could read it in the Constitution every Sunday morning from the Federal Reserve reports: retail sales in Atlanta down for the fifth week. We kept a picket line up around the store, mostly with students, but I remember one time we had a picket around the whole downtown area, 1,400 or so people, from the housing projects and campus. We had two-way radios; we had a succession of volunteer cars coming every day; we had women from the community who brought food in at lunch time for the picketers. We had heavy football jackets from the athletic department at Morehouse for the girls to protect them from blow guns and spit. And we had all weather, laminated picket signs. It was quite an operation. . . . Those were really fantastic times for all of us.

We —the students—were doing most of the work, but the whole community was pulled in. And it revealed to us many of the splits within the black establishment and the movement. We finally got Dr. King to go down to Rich’s and get arrested. We went to him and said, “You’re not doing anything; come and get with us. You’re from Atlanta and these are Atlanta students from your alma mater.” King really didn’t have much of an organization at all then. SCLC was just a few people. But when he moved back to Atlanta from Montgomery, after the bus boycott, he was viewed as a threat by many of the adult leaders. This is a very, very tight town, and they were interested in political power, electoral power, which King was not concerned about at that time. He had a national agenda and they were afraid he would hurt their local interest in political power. You see, this was about the time Q. V. Williamson had been picked to be the single black candidate for the board of aldermen of Atlanta in a deal with the white power structure. At that time, we were a minority vote, but a very disciplined vote. It was disciplined by the Atlanta Negro Voters League, which on election eve would pass out a ticket printed on bank-note paper that couldn’t possibly be imitated or duplicated. This was the ticket; there was no other. Now you can stand up at the poll and get 20 of them. And actually, it was fairly democratically done then; these were endorsements by people you knew, with their names on the bottom, the ward leaders and party chairmen. Candidates went before the League and got their endorsement, but they couldn’t buy the ticket like they can now.

Anyway, we got Dr. King involved in the boycott and other groups came in, and finally we began negotiations with Ivan Allen, who was then president of the Chamber of Commerce, and other whites on one side and some students and more adults on the other. We finally got an agreement which was a terrible agreement. It said, first, that the boycott would stop, and secondly, that the stores would integrate on a timetable of their own choosing, and thirdly, that if there was any violence over the integration of the public schools, which was going on then, they wouldn’t integrate the stores at all. We held a mass meeting across the street from Mt. Moriah Baptist Church to announce the agreement, and on the platform were Lonnie and Hershel Sullivan and Daddy King, Sr., and a couple other adult leaders and Martin Luther King, Jr. The crowd was incensed, bitterly angry with the agreement. They repudiated Lonnie, repudiated Hershel, and almost had them in tears. I remember one woman in a nurse’s uniform storming down through the crowd saying, “I didn’t give up shopping at Rich’s for a year for this!” They called Daddy King an Uncle Tom, and I don’t think he had ever been called that before. But then Martin made a speech, and I have never heard such a masterful speech. It was on leadership, and it said, in effect, you have to trust your leaders even when they don’t do what you think they ought to. He really played the audience like a violin; he lifted them up and let them down, lifted them up and let them down, lifted them up and let them down, and the last time he was through—and the stores did integrate on a fairly regular schedule. I remember the day Rich’s integrated. They wanted us to send testing teams, and so the word went out, and some matrons in the community who had never lifted a finger to help us wanted to be among the first. So they went down to integrate Rich’s wearing furs and hats and so on —I mean, just to go eat lunch.

Southern Exposure: What were you doing during this period, from the spring of 1960 into the summer and fall?

Bond: I was the publicity guy, sending out press releases all over the country to the black press and keeping in touch with local offices of the national press: Time, Newsweek, the New York Times and Washington Post. I became the publicist almost immediately because I was interested in writing and could write a press release that other people could understand. I had been active in a literary magazine at Morehouse, and Lonnie probably volunteered me from the beginning to be the press person. And I enjoyed that very much.

Then in the summer, when the students left, we moved from sitting-in at lunch counters to picketing job targets. One of the main ones was the A&P on the corner at Hunter and Ashby. You know, here is this almost all-black A&P, but it had only one black employee, a bag boy. We started our picket, but we didn’t have the community support that we needed because there was no information about what we were doing reaching people. We knew they would support us, if they just knew what we were doing. It turned out the A&P was one of the biggest advertisers in the Atlanta World, so they put pressure on the World and the World began to attack us. They had always been very conservative, but this was the final straw; we knew we needed our own media. So we started publishing a newsletter every Saturday night and every Sunday we would go out and distribute thousands of copies at churches, and it really caught on. We had news of what was happening with us—“the boycott is in its third week.” And I was hot on those Federal Reserve numbers, you know, to show we were winning. Then there was other news; I wrote most of it myself. Then a group of liberal businessmen who were also discontented with the World, but who wanted a black medium too, approached us and asked us to help start a new regular newspaper. So we left our newsletter and I went to work for the Inquirer.

Southern Exposure: What about the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), your role in that and its relation to Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)?

Bond: Well, I left the Inquirer to go work in the SNCC office full-time. SNCC had been formed in April, 1960, at a conference in Raleigh called by SCLC, or really by Ella Baker as her last act before leaving SCLC. It was that same spring following the Greensboro sit-ins, when there were boycotts and picketing and sit-ins in towns all over the South. So the conference brought together all these students— maybe 500 of them-with observers from the North and organizations like the National Student Association (NSA) and civil rights organizations like NAACP, CORE, SCLC. Everybody wanted us to be their youth affiliate; they were all lobbying us. But at that time, we were suspicious of them all, including Dr. King since he hadn’t sat-in anywhere then. Sitting-in was the test —and also what everybody was talking about, trading brutality stories. We decided we didn’t need these older people telling us what to do or capitalizing on what we did, so we formed an independent, temporary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to be just that —“coordinating of students” — and to plan another conference for October of that year in Atlanta to make a permanent SNCC.

So by the middle of 1960, SNCC had an office here in Atlanta which Jane Stembridge first ran, then Ed King, then James Forman. Forman came by the end of ‘60 because SNCC began putting paid people in the field and we needed somebody with very good organizational abilities to head up the Atlanta office and keep a supply line going into the field. When he got here, he looked through the files and saw that I had done publicity work for the local Committee, so he called me up and asked me to do the same work for SNCC. I dropped out of Morehouse altogether in January, 1961 — and didn’t go back to graduate until 1971-and gave up the newspaper work. There were four of us in the office then: Forman, Norma Collins, myself and John Hardy, who got brutally beaten in Walthall County, Mississippi, and who loved to dance in the office. And we had a tiny office down on Auburn Avenue —not too far from SCLC.

I can remember Forman and I going into the bank to deposit two or five dollars, and seeing Wyatt Tee Walker, who replaced Ella Baker as head of SCLC, in his pressed blue jeans depositing sacks of checks. It was irritating as the devil because we knew we were the people doing things. King was going around making speeches, but that was it; they didn’t have anybody in the field hardly. But they were getting all this dough, much of it, I’m sure, marked “To Southern Students, c/o Dr. Martin Luther King.” The southern civil rights movement was just known as SCLC. Of course, that quickly changed with my marvelous press work! Also, we finally got King to agreed to give us a subsidy of about $500 a month, I think. Forman arranged that personally with King.

Southern Exposure: The period from 1960 through 1964 while SNCC was at its heyday was a time of tremendous movement and activity for a great number of young people—kids, really. Can you sum up some of the changes that people went through and some of the lessons that were learned about how power works?

Bond: Well, the first lesson we learned was that the early naivete of the movement was just that: naivete. We were operating on the theory that here was a problem, you expose it to the world, the world says “How horrible!” and moves to correct it. Now that worked in certain situations, like a lunch counter or the horror of police brutality in Birmingham in ‘63. People were shocked and did say “My God, let’s do something about it.” We thought there was even a hidden reservoir of support among white Southerners which was largely fed by our positive inter-racial contacts with white southern students. And we thought that the Kennedy administration was on our side and that, again, all you had to do was put your case before them and they would straighten out what was wrong. Or all you had to do was register voters, turn them out on election day and snap, everything would be taken care of: streets would be paved, jobs provided, houses built, facilities integrated. But gradually we learned different. We saw from working in the rural South who our friends really were, and it wasn’t the parents of these white students or the Americans for Democratic Action, but it was people like the National Lawyers Guild whom others had told us not to work with because they were communists or radicals. I remember especially when Kennedy was killed, we had these tremendous discussions over what this meant for us: “Who is this guy Johnson?”

So we began looking over the longer haul and realizing we were talking about upsetting much more deeply ingrained institutional economic arrangements which were, first, difficult to dramatize, if their daily reality wasn’t drama enough, and second, difficult to get people of privilege to care about changing. Therefore, we were forced to think about amassing a power of a different kind than that derived from moral suasion. And to the movement in the South, there were only limited alternatives. One was political power, which the movement really got into heavily in 1964 with the Freedom Democratic Party in Mississippi, and from then on with the developing of independent political power, which meant moving away from mass marches to a different kind of organizing. Second was independent economic power, by which I don’t mean the ability of blacks to become millionaires, but their ability to control their own economic resources, to build some independent economic structure.

Now these lessons were learned very gradually in the early 1960s and after some disappointments. And they were learned mostly from discussions with each other. Of course, within SNCC there were various differences of opinion which came out particularly in the ‘64 Mississippi Summer and when economic issues were raised and the Vietnam War began to be raised. I can remember that the war was first raised by the students from Howard University who were generally the most sophisticated politically of all of us, were heavily influenced by Bayard Rustin, and were coming from Washington where you are much more likely to be involved in discussions of foreign policy. Well, to many of us from the South, the Howard people were sort of New York sharpies, you know, Stokely Carmichael, Courtland Cox and later Charlie Cobb; and we weren’t thinking about the war much at all. I had gone down and taken my physical and been declared unfit for military service because of my arrest record for demonstrating. But gradually, we began dealing with it more seriously, both because northern college campuses where we were going to raise money were asking about our position on the war, and more importantly, because we saw our staff members being disproportionately drafted, selectively drafted. It became a personal thing. It was finally precipitated in December of 1965 with the shooting of Sammy Younge, who was a veteran. So, you know, we learned that lesson, that even if you were a veteran, they would shoot you down if you worked for civil rights in America. We drew up an anti-war statement for the press which made all these parallels between what we were doing and what the Vietnamese were doing, and our opposition, you know, both calling us “outside infiltrators and agitators.” We were the American NLF, guerrilla warriors which, of course, is a long way from thinking the government is on your side.

There were other things we learned as the years wore on. For one, we began to realize that our broad brush approach wasn’t going to solve the complex problems we were coming up against. What was needed was more of a specialist approach to work on specific parts of the problem. Two things helped this development. One was the evolving of people’s individual interests. You know, you might have five or six people living and working together in a small town, literally thrown together, and while their day was incredibly busy, 18 hours a day, and quite often under tremendous danger, one of them would think of something new that needed to be done. Somebody would say, “Here’s a real need we’re not meeting,” and begin to fill it. The other thing that happened was that the poverty program created these little special interest projects, a consumer co-op in a town in Mississippi, a day-care center in Alabama, and created this group of people (really almost a bureaucracy) tied to the notion that you had to focus on something. You couldn’t continue to, as we used to say in the very early days, have a card which said “Have Nonviolence, Will Travel.” Today, there are a whole group of people who have come out of the movement, who are no longer the SNCC generalists, but who have taken the movement into their life’s work through concentrating in one area.

One other thing that goes with this that I guess we learned was that you had to construct your own alternatives. On the one hand, you held out a vision of what society ought to be, and at the same time, you tried to construct a working model of one aspect of what it could be. The day-care example is instructive. We didn’t just make the demand for federally subsidized daycare, which is what should happen; we went out and set up a day-care center in the town. And while we were constructing this model, we were learning to do it ourselves; we were providing a service to people who needed it; we are instructing children in a different way than they would get at home; and so on. Now that did not happen in my view as often as it should have, but it did happen in many towns around the South and the country, and many of the people who did it had been leading marches or registering voters two or three years before.

Southern Exposure: Did your own interest push you in the direction of the electoral arena? Were you energetically moving to become a candidate in 1965?

Bond: I didn’t move at all energetically. What happened was that the opportunity came for the first time since Reconstruction for Georgia to elect black candidates to the state House of Representatives. (There were already two state senators.) A new district was created, which meant no incumbents were running, and that meant SNCC people who had been promoting political participation in the rural South had to come to grips with the question of politics in the urban South and with thinking in terms of Democrats and Republicans seriously. This chance just presented itself for us to win a seat in the state house. And it turned out I was the only person from SNCC who lived in the district. Now this was an important difference between me and other people who were out-of-towners, who had left their homes to go to another city, some of them at age 17 or even younger, and for whom their civil rights work was everything. I was at home in Atlanta, and had maintained, you know, contact with people in the larger community, so this work was not a real interruption or discontinuity in my life; I wasn’t out of place. People knew me not only from my publicity work for SNCC, but from the picket line at the A&P back in the summer of 1960 and from the voter registration campaign at Egan Homes and University Homes the next summer, so I could campaign with that history, you know: “Remember that picket line that we did and now there are black people working there.”

I had really not given any thought to running for office, but when this chance arose a friend of mine who was active in Republican Party politics asked me to run as a Republican, and then another friend asked me to run as a Democrat. Well, I began to think there must be something to this, and asked myself did I want to be a candidate of the party headed by Barry Goldwater or of what we referred to as “the party of Kennedy.” So I became a Democratic candidate, and the three people who helped me the most were, of course, all from SNCC: Judy Richardson, Charlie Cobb and Ivanhoe Donaldson. A tremendous amount of scorn was heaped upon us from our colleagues in SNCC because we wore neckties while campaigning and because we didn’t construct an independent candidacy. Our immediate answer was that we didn’t want to get into arguments with people about our clothes and that the law in Georgia was so rigid that an independent candidacy was next to impossible, given our time limitations. On the whole, most SNCC people were very supportive; people would pass through town and spend a day canvassing and knocking on doors. We put in a great deal of work and won without much serious opposition.

Southern Exposure: What did you think political office meant?

Bond: At the time, I thought the people in the General Assembly were unrelenting racists, to a man, and, in fact, some are and some aren’t. I thought also that there would be this tremendous ideological debate in the Assembly, but in fact, even when the issues are class issues, they are rarely discussed in those terms; more often, it’s a question of dollars and cents. And then, I think I had a rather idealized view of “total democracy,” that I would find some way to ask my constituents how I should vote on every single measure. But I have since concluded that it is not possible or practical because I am called upon to vote 40 times a day. The decision is ultimately mine. I now take the Edmund Burke view that your representative owes you not just his loyalty but his conscience and if he sacrifices either, then he sacrifices his right to represent you. My conscience is what ultimately tells me to vote yea or nay on a question, but every two years a referendum is held in my district over how well I do, over my manner of behavior in the legislature.

You know the debate between the community-based political activists and the electoral activists over who’s responsible to whom? Mv thesis is that unlike almost every other leadership segment in the black community, elected officials alone have a responsibility that is re-enforced on a regular basis. I have a two-year option with the people I serve, and they either renew it or not every two years. But the large bulk of community activists tend to be self-appointed and cannot identify their constituents readily, who they are and exactly what their interest is. It may sound like a bicentennial speech, but I really believe that this political office is a sacred trust. People have gotten together and made a choice and entrusted me with their lives in a certain sense. I’m their representative. That’s serious business. You can’t fool around with people’s trust.

Now, in addition to my strict role as a legislator—which is something I had to learn over a period of time, how the legislature works —I also have to be someone people can call upon for help, not just a symbol of someone black in the legislature, but actually serving as sort of an ombudsman between people and their government, helping them get their social security check or whatever it might be they call me about—and usually it is not even a matter of the state, but of the city or federal government. That’s why this office here in the district is necessary. Normally, I wouldn’t need it. Of course, sometimes I can’t help at all. A woman called me yesterday and said her boyfriend wanted to be a black leader and she wanted me to interview him to see if he could make it. I had to tell her I wasn’t on the screening committee. (Laughs)

Southern Exposure: What do you say to people who say the whole arena of electoral politics is irrelevant or a cop-out?

Bond (still laughing): I say, “Poohpooh to you.” I say, “That’s not true.” I agree that if you think that registering to vote and electing decent people is sufficient by itself, then you are naive —but I do think that it’s very, very important. What I think has happened is that the people who say it doesn’t make any difference at all have simply righteously rejected the rhetoric of the people who say it makes all the difference in the world. There is a middle point. It clearly does make a difference who the President or Congress is. Just think in terms of social services or the number of people who could have jobs in this country. If Hubert Humphrey, as a bad example, were President today instead of Gerald Ford, I think things would be much better for poor people in the United States. That’s not to say we’d have full employment or a completely equal distribution of resources, but simply that elections do make a difference, a very important difference.

Southern Exposure: Speaking of Hubert Humphrey, how did you get involved in the challenge at the Democratic convention in 1968 that got you nominated for Vice-President?

Bond: Well, I got involved in the ‘68 convention really by happenstance. You know, one of the great critiques of my life is that fate at every step has opened the door and I have just stumbled through. What happened was two young white men, Parker Hudson and Taylor Branch, were interested in getting a single Eugene McCarthy delegate from Georgia elected to the Chicago convention. That’s all. But they quickly found out all the delegates from Georgia were appointed by the state party chairman who was appointed by the governor, which meant Lester Maddox. There was no provision for citizen input at all. The AFL-CIO, which wanted delegates for Humphrey, was also unhappy with this, so together with the McCarthy people, they held a convention in Macon to choose a challenge delegation. I just drove down there with some friends, and the McCarthy people, who swept the convention from the Humphrey folks, asked me to be the chairman of the delegation. I had had no idea of going to the convention at all before that! So I agreed not to be the chairman, but the co-chairman with Rev. James Hooten of Savannah.

Well, a few of us went to Chicago to present our case to the credentials committee, you know, saying that we were more representative than the Maddox delegation from Georgia. I had gone to Chicago with no suitcase, thinking we would just tell the committee the facts and go back home and wait for the answer. But the credentials committee is not like a regular jury. They’re not locked up at night; they go to cocktail parties, to caucuses, to meetings; you can get to them. So, it became clear we needed our whole delegation up there to lobby the committee. But we had no money, and the bulk of our delegates were really working-class, poor people from rural Georgia who couldn’t afford to pay their way. So it fell upon me to raise the money. I finally got $3,000 from a source that I’m not at liberty to mention —but which would surprise the devil out of people if they knew — and went to Delta and bought their tickets and in 24 hours they were in Chicago. They in turn became lobbyists, hitting all the delegations because we knew even if we didn’t have the votes to win in the credentials committee, we had a chance of being seated by a vote from the whole convention.

We never saw the white movement protesting outside because we, even more than most conventioneers, led a very sheltered existence. But it did quickly become evident to me that what was involved here was a vast civic lesson for America, that all the country was watching and that all of us were acting out the very basics in political science. Here we were turning out members of the regular Maddox delegation, many of whom were state legislators who had voted two years before to put me out of the state house because of the anti-war statement we made in SNCC. There’s an old saying: “What goes around, comes around.” It sure does, in politics especially, every time. We were literally putting these guys out, sending them home.

Southern Exposure: Was your involvement and the involvement of other blacks inside the convention as consistent with the development of the black movement as the protests outside were consistent with the course of the white left?

Bond: Yes, it was an extension of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party challenge in the 1964 Atlantic City convention. In fact, this was the convention in which the FDP was seated and recognized as being the official Mississippi delegation. And then, too, we were on the inside believing we had a very good chance to have a President made by people who are on the fringes of regular politics. To us, it was a tremendous demonstration of power. We were, one, challenging racism and this totalitarian scheme in Georgia; two, we, as a delegation of people who had been excluded all our lives, were coming into political power and prominence in Georgia; and three, we were electing the President of the US. What more could you ask?

I’ll tell you something else. A great deal of the black movement’s perspective about the street demonstrations were reflected in what Bobby Seale or somebody said, namely that black people knew the police in Chicago and in the big cities and wouldn’t put themselves in a position of being beaten or worse. What happened was predictable.

Southern Exposure: Do you think the anti-war movement made a mistake by continuing to attack Humphrey after the convention without considering what the consequences would. be if they succeeded in knocking him off?

Bond: Well, I campaigned very hard for McCarthy, and I can understand the emotional investment people had in him. But when it became a contest between Humphrey and Nixon, I was urging people to vote Democratic. So overall I think it was a mistake not to see what would happen. Humphrey could have been President very easily in 1968, and I’m not making a campaign speech for him, but, you know, instead we had six years of Nixon —the country pushed to the right, the Supreme Court and on and on.

On the other hand, those of us in the challenge delegation made a mistake by not coming back to Georgia — and I have been rightly criticized about this —to begin an independent political organization which would be in operation by the next year for the governor’s race. Instead, we pretty much went our own ways.

Southern Exposure: What about your own interest in a presidential campaign? Why do you want to be President?

Bond: Because as Theodore Roosevelt once said, “It’s a bully pulpit.” In other words, you have a chance to put your ideas and programs before the whole public, the Congress particularly, but the whole country. This goes for the campaign as well. If I ran, I wouldn’t want to be just a black Eugene McCarthy or a black Bobby Kennedy. I think you’ve got to run a very different campaign, you’ve got to move much further to the left. It’s got to be as black as you can make it without turning off the white electorate. You’ve got to talk about very serious economic changes. It’s got to draw a vast number of people into a movement around basic issues of power, people who might be out there holding or waiting —like in the early movement—without even knowing it, waiting to be involved.

Southern Exposure: Do you really think America is ready for Julian Bond as President? I mean, it’s been only ten years since you were blocked from taking your seat in the Georgia legislature, and ten years before that, you as President would have been hardly imaginable. Do you think social change happens that quick, that America has changed that much?

Bond: No, but I think it could have changed that much. I think we in the movement in the early ‘60s have missed several bets along the way. Among the greatest was the inability to sustain over a long period of time. Take the Freedom Democratic Party in Mississippi as a small example. The FDP is in disarray now; they have Democratic Party recognition as the loyalists, but little else because they weren’t able to sustain. Mississippi is 40 percent black, but why haven’t they been able to do better, to elect more blacks? It’s not just because of the evil of white officialdom. The organizers on the scene and the support people back here didn’t keep at it enough, didn’t organize enough, didn’t do as much as we could have. Now this is not just a problem of organization, but, more importantly, it is a problem of keeping people involved.

One thing SNCC did in those early days was provide a funnel through which the activist young person could pour himself or herself and come out at the bottom directed toward something they could become involved in, could become a part of. There’s nothing like that, now; we’ve lost our ability to sustain that funnel. For SNCC, it broke down for external and internal reasons. The external reasons were beyond our control: our anti-war pronouncement in ‘65 and particularly the position taken on the Arab-Israeli war by a sector of SNCC in ‘66 or ’67 eliminated our financial support, and the anti-war movement sucked away more money and support. At the same time, we never created the national ongoing support structure that would sustain us over a period of years, which is a problem that other groups have. SCLC has always had it and the NAACP is having it now. So we weren’t able to keep the funnel open. We narrowed its top and we narrowed its center and what came out the bottom ceased. People in their local communities were left to their own devices, unable to make the kind of national or regional connections they had once made. And some of them were—and are still—attracted to other mechanisms, from those with a certain romanticism like the Black Panther Party, which was, I hesitate to say, an illegitimate child of the civil rights movement, to groups that are really very disturbed and deranged. And they will continue to be attracted to them because they don’t see any alternatives.

Southern Exposure: What do you advise people to do in order to recreate these funnels? Would the creation of a leftist third party provide the kind of mechanism needed to allow large numbers of people to participate in social change activities again?

Bond: Well, we need that, but that may not solve this problem of having funnels. I mean, there are some alternatives now for people to go into, but they are not known, that is, people don’t know they can contribute anything to them or can become a part of them in some way that accommodates their other commitments, you know, like school or a job or a family. The organizations we do have have failed to propagandize themselves or somehow project themselves as a funnel that people can give something to, you know, not just financially, but can contribute their creative talents, whatever they may be, within a framework that gives them value. Take the Institute of the Black World, or the Institute for Southern Studies for that matter. Even if we had a third party right now—and there are plans to run a third party presidential campaign next year—what would the Institute for Southern Studies be doing to provide that funnel on a sustained basis? Well, I can see where it could be commissioning papers right now on certain subjects, not for party purposes because of the tax-exempt status, but analyses and model programs on conversion of military bases or allocation of natural resources or public ownership of public services and utilities or whatever, and these papers could then be used by a third party or by any candidate for that matter. There are scores of people in academia in the South who would be eager to do that, but I don’t think they feel there’s any structure they can do it in which would assign such work any real worth. You know, who would see it, who would publish it, who would use it? Well, that’s just one thing the Institute and Southern Exposure could be doing to serve as a funnel, whether there is a third party or not.

Southern Exposure: If that’s an example of where you think organizations should be headed, where do you think the movement in general, and the black movement in particular, is now?

Bond: In my view, it is a localized movement: the smaller the town, the more inclusive the organization running it may happen to be; the larger the town, the more fragmented it is, which isn’t to say that organizations are working at cross purposes as much as that they don’t work under any umbrella. It doesn’t have any national cohesion and very little regional cohesion. But in small southern towns especially, I think it is a movement that focuses on those areas of power that I mentioned earlier, that we learned we had to move into, namely it is a political and economic movement. It’s political in the sense that it’s trying to create a black mercantile class of small businessmen, shopping center owners and so forth, and in that it’s largely a movement oriented at winning existing jobs. Sadly enough, it’s not a job-creating movement, which is an important mistake, I think. By that I mean if you go to Pascagoula, Mississippi, or Greenville, South Carolina, people are making demands on the ship builders or textile mills to share the existing jobs equitably. They want to integrate within the existing job structure, so it’s not a movement that thinks about a reorganized economy or about alternative structures. Instead of competing with another guy who is out there looking for a job, the movement needs to point out that the way the economy is run now is too limited and we need to project an alternative way to run it. This gets back to what I think has been a continuing failure of the southern movement to do the kind of planning we were talking about with those commissioned studies. We have to look ahead five, ten years for a different way to finance the government and structure the economy.

Southern Exposure: Would you propose some kind of quasi-socialist or socialist control of American corporations?

Bond: Yes, I do that in my speeches, particularly for the expanding sector of the economy which is services. That’s where the new jobs are going to be, so the question is whether it is privately controlled or part of the public sector. I say we should have local and national control of public services operated for need and not for profit and a free health system financed from the national treasury and not for the insurance companies, a redistribution of wealth through a tax structure that eliminates the disparity between the needy and the greedy, a national work force plan and so on.

Southern Exposure: Why do you think the media doesn’t reflect the kind of radical beliefs and programs you advocate?

Bond: I’m not really sure. You know I go places and say things that I don’t think many people are saying to audiences, but when I read the newspaper account of my speech something is lost. I was down in Austin, Texas, and talked about structural and economic changes and was using as a basis for my talk a platform of the California Democratic Socialist Party. But, you know, here’s the news report and it’s just not there. They give me this image and I don’t know how to correct it.

Southern Exposure: You don’t work to develop your image?

Bond: No. I just do, you know, go out and do.

Tags

Julian Bond

Julian Bond was a founder of the Institute for Southern Studies and served as its president for several years. He was the communications director of SNCC, served in the Georgia state legislature, and was a professor at the University of Virginia.

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)