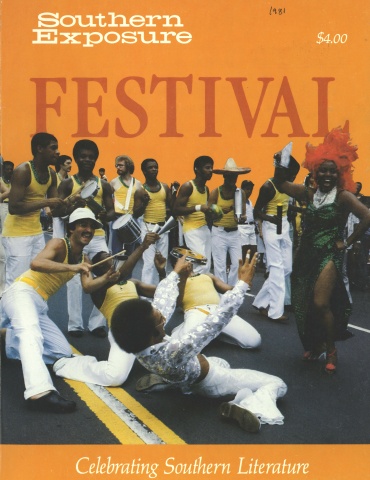

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

It’s a tradition at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee. When the autumn moon is high and all the listeners have gathered close round a crackling fire, Kathryn Windham will lovingly share a ghost tale, filling the air with a lilting Alabama accent that is as thick as homemade apple butter. She’s asked to return every year because she’s the kind of teller who has as many tales to tell as there are listeners to hear them.

Kathryn Windham of Selma, Alabama, collects the stories that still haunt the valleys and peaks of our Southern mountains. She is the author of 13 books, including six collections of ghost tales, four cookbooks, two histories and one on superstitions. Her history textbook, Exploring Alabama, is used in several schools, and her Alabama: One Big Front Porch won the Alabama Library Association Award for the best nonfiction book of 1975.

An organization in Selma recently honored her by presenting a “Kathryn Tucker Windham Girl of the Year Award.” The townspeople know that her life is exemplary for area Southern women, that she is one of those whose obvious love of life and people enables her to accomplish anything she sets out to do.

As the unofficial matriarch of the story revival movement, Windham was the first member of the National Association for the Preservation and Perpetuation of Storytelling (NAPPS), and she has served on the organization’s board of directors since its conception in 1975.

Kathryn believes in telling stories and preserving them. She sees this as a way for people to renew their humanity in an age dominated by modern mechanics and superficialities.

“I think there’s a hunger for that one-to-one relationship that story telling is,” she said, leaning in closer for emphasis. “When you tell a story, you’re giving a part of yourself. That’s the reason we’re having this revival. People are hungry for something basic and real. They come to the festivals because they want this tale that somebody has been saving to share with them — that’s the feeling of a good storyteller, that this is something I’ve been wanting to tell you.”

But the simple sharing of a tale does not encompass the whole of Kathryn’s purpose. It acts rather as a pleasurable by-product. The real impetus lies in the authenticity, the real blood and guts that were spent in the making of the tale. What concerns her is that many of the stories are slipping away and with them a wellspring of strength and knowledge. Indeed, it is a reverence for all that has gone before that is at the core of Kathryn Windham, something she most likely acquired from growing up within a close-knit Southern family.

“When I was growing up we never had any money,” Kathryn said. “But we always had books, and my father was the finest storyteller I’ve ever listened to — a natural storyteller. We had a big porch on our house and we would sit out on the porch after supper on summer nights and my daddy would tell stories. I knew tales about my grandparents and uncles, about people who lived before I was born.

“I knew about them and I knew who I was. ... I think storytelling is part of what it’s all about,” She paused, letting a faint smile spread across her face. “I was the youngest of the family and I think Papa enjoyed me more. He’d take me with him to historical sites, where Indians had fought or where Civil War encounters had been. There wouldn’t be anyone there but my daddy and me, but the whole thing would come alive. So to me that’s what storytelling has always been, a personal thing — a sharing of something that’s important to you.”

Kathryn grew up during the 1920s in Thomasville, a small, unpretentious town on the southwestern edge of Alabama. After high school, she attended Huntingdon College in Montgomery, taking a job there after graduation with the Alabama Journal. Then she moved on to become state editor and feature writer for the Birmingham News. She had a good job and a promising future, when she met and married Amasa Benjamin Windham.

Both Benjamin and Kathryn wrote. Both were sensitive, creative and hardworking. Then in 1955, Benjamin suffered a heart attack and died. Suddenly Kathryn was left a widow with three small children to bring up alone. She was 37 years old. When Dilcy, her youngest, entered public school, Kathryn returned to news paper work, this time in Selma. And, after several years had passed, she began work on her volumes of Southern ghost tales.

NAPPS

The First National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee, was conceived by local businessman Jimmy Neil Smith, a young man who loved to hear good stories. Fie got the idea as he and some friends listened to storyteller Jerry Clower on a car radio one day. “Why not get a group of storytellers together in Jonesboro and see what happens?” he said excitedly.

At first the idea of a “national” festival seemed too far-fetched, especially for a small town like Jonesboro. But with the help of a local civic group, the first festival was held. What resulted was an explosion of energy, a coming together of the old and young, the past and the present, in a passionate sharing of the spoken word.

That was seven years ago. Since those early days the annual event has come to be recognized as a culmination of all facets of the art. And the National Association for the Preservation and Perpetuation of Storytelling is now the spearhead for a national revival of the art.

The association, founded in 1975, and better known as NAPPS, sponsors the national festival and a national conference on storytelling every spring. In September, 1977, it put into daily operation the National Storytelling Resource Center, which contains a resource library and archive housing one of the most comprehensive collections of audio and video storytelling recordings in the nation.

The effort to save storytelling from extinction is well underway, but there is much left to do. Those interested in finding out about membership or other services of NAPPS should contact it at P.O. Box 112, Jonesboro, Tennessee 37659.

“I kept coming across these ghost stories,” she says, “and everywhere I went people had more and more stories to tell. It didn’t matter that most folks don’t believe in ghosts. The important thing was that they be collected and preserved.”

Soon the project consumed most of her time. Every weekend was spent following up on some purported occurrence of the supernatural, some strange unexplained happening. She would listen to different ghostly accounts, then check local histories related to the events of the story.

At the same time her interest was whetted by some rather bizarre happenings at home — footsteps that clumped when no one was around, doors that slammed mysteriously, rockers that rocked all by themselves. It didn’t take Kathryn and her family long to conclude that some disembodied, free-floating something had taken possession of their home.

Kathryn’s eyes sparkle when she speaks of her ghost, Jeffrey. He is a pleasurable diversion from the more serious reality of her mission — that of preserving the stories that vividly reveal how the events of the past serve to alter the people and the ongoing happenings of the future.

She sees how her own upbringing in Thomasville and the many hours of storytelling at her father’s knee affected her own view of the world. She believes a similar process dramatically affects the works of many writers who grew up in the South.

“I believe that Southern writers have been lastingly influenced by stories they heard as children — writers like Eudora Welty, William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor. For example, they got some of their characters from stories they heard. I think they learned to listen and become aware of the dialects, inflection of voice, the ways of expressing things or the rhythm of the language, which you do become aware of by listening to stories.

“Storytelling has aroused their interest in people and in things around them. And it accounts for the fact that there are so many good writers who have come out of the South. They deal more successfully with how people are related to the place in which they grew up. I think the two are inseparable. Where you spend the formative years of your life marks you for the rest of your life, and I think Southern writers are more aware of that than others.”

Kathryn is now preparing another volume of Alabama ghost stories and has plans for several books — one about women who commanded steam ships and another on Southern folk lore. She also wants to continue her work in NAPPS and with the Tale Telling Festival, an annual event in her own town of Selma.

But no matter where she goes or what she does, Kathryn Windham will always know that she is still that skinny tow-headed girl from Thomasville, carrying with her the memories of her father settling down on that old wooden porch to share just one last tale or two. And for the rest of her days, she will, in all likelihood, spread the good news of storytelling as she remembers it.

As Kathryn says in her book, Alabama: One Big Back Porch, “The tale tellers don’t all look alike and they don’t all talk alike, but the stories they tell are all alike in their unmistakable blend of exaggeration, humor, pathos, folklore and romanticism. Family history is woven into the stories. And pride. And humor. Always humor.

Tags

Jill Oxendine

Jill Oxendine is a free-lance writer who produces the NAPPS monthly newsletter and works part-time in public relations for the Quillen-Disher College of Medicine in Johnson City, Tennessee. (1981)