This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

In the late 1930s, Hallie Flanagan, the national director of the Federal Theatre Project declared, “Shakespeare and circuses, musical comedy and modern satire, theatres for children and youth, dance theatres, living newspapers; marionette theatres, vaudeville and variety, classical theatres made vibrant for modern youth, radio, theatre of the air — all of these are in the province of a living theatre sponsored by the government of the US.” Although others — especially some Congressmen — did not share her vision, for four years (1935 - 39) the Federal Theatre Project became a national “people’s” theatre, as it fulfilled its primary task of providing jobs for unemployed theatre professionals.

The most visible and controversial of the five WPA Arts Projects (the others covered music, art, writing, and historical records), the Federal Theatre Project produced over 900 full-length plays and employed over 12,000 theatre personnel. Many of the people it employed were performers, like vaudevillians, who knew a skill that was no longer in demand; others were young people just getting a start in their chosen profession. People like playwrights Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams (in New Orleans), producer John Houseman, directors Joseph Losey and Orson Welles, set designers Howard Bay and Ben Edwards (from Alabama), lighting geniuses Abe Feder and George Izenour, composers Lehman Engel, Virgil Thomson, and Alex North, and actors Will Geer, E. G. Marshall, Arlene Francis, Joseph Cotten, and John Huston all established their reputations, in large part, through jobs with the Federal Theatre.

The FTP also created new theatres and audiences, and significantly advanced American stagecraft. The out- Poster Announcing FTP Play door theatre in Manteo, North Carolina, was built with WPA funds, and Paul Green’s The Lost Colony, which is still produced at Manteo every summer, began with Federal Theatre actors. The Project also brought into the theatre groups that had always been on the outside. Black units were established from Birmingham to Seattle, giving black writers, artists, actors, and directors the opportunity to step beyond the stereotyped roles which had usually been assigned to them in the past. Although black and white units normally did not mix, and each group usually produced its own plays, budget and personnel cuts and casting demands of particular plays did bring some of the units together. Ethnic communities across the country enjoyed Federal Theatre productions in their native tongues, from Yiddish in New York to Spanish in Tampa. The FTP also produced new plays for children, the audiences of the future. Marionettes for both adults and children were a FTP favorite, and special units were established in Miami, Jacksonville, Durham, Goldsboro, Oklahoma City and Dallas.

The Federal Theatre was organized by geographic regions to give local units more autonomy and to encourage the production of regional theatre. Theoretically, wherever ten unem- ployed theatre professionals were located, a unit could be organized. But from its inception, administrative reorganizations and budget cuts forced the FTP to consolidate. For example, the Florida Project started with twenty-two units in 1935; within a year it was eleven, then seven, then finally three. The Southern region began with units in North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas. These groups ranged from the Carolina Playmakers, associated with the University of North Carolina and specializing in folk drama, to the old stock companies of New Orleans and Atlanta, to radio performers of Oklahoma City.

Most of the productions of these units were the old, safe fare that stock companies and vaudeville troupes had staged for years. Some of the units toured the surrounding countryside, bringing theatre to many people who had never seen it before. The North Carolina players alone performed regularly in over half a dozen cities. The Jacksonville unit developed a “history of drama” series which was staged in high schools throughout northern Florida.

Occasionally the Southern units responded to particular community issues or to Hallie Flanagan’s plea that “the theatre must be conscious of the implications of the changing social order.” When the Federal Theatre organized twenty-two simultaneous openings across the nation of It Can’t Happen Here, a dramatization of Sinclair Lewis’ novel about the rise of Fascism in America, Birmingham, Miami, and Tampa were among those cities which mounted productions. Another topical play, If Ye Break Faith by Maria Coxe, premiered in Miami and was later produced in Jacksonville and New Orleans. And an antiwar play, in which the six unknown soldiers from Europe and America return to try vainly to convince others about the waste and uselessness of war, was well received in the same three cities. The New Orleans States described it as the “most difficult and most impressive offering the Federal Theatre has had before the public.”

But for the most part, the Southern units seemed reluctant to stage plays about their own region and history. In fact, New York City produced more plays about the South — from the biographical Jefferson Davis to the melodramatic Big Blow (about a Florida hurricane) — than all of the Southern companies combined. Productions considered controversial in the North were simply too volatile for audiences in the South. Consequently, plays on topics like tenant farming, such as Conrad Seiler’s Sweet Land, or J.A. Smith and Peter Morell’s Turpentine, were only performed in the North. And even there they still managed to provoke the wrath of the Southern establishment. In fact, a Savannah weekly, Naval Stores Review and Journal of Trade, labeled the New York production of Turpentine “a malicious libel on the naval stores ’industry of the South,” and suggested that “Southern Congressmen could properly protest...the play’s author’s hope to better conditions in the Florida camps.” And two years later, when the FTP was struggling to get refunded, protest they did.

There were, of course, important exceptions. The New Orleans unit staged Gladys Ungar and Walter Armitage’s African Vineyard, the only effort by a white company to confront the race issue. In that play, the setting was South Africa, the conflict between the English and Dutch attitudes towards life, land and blacks; it was left to Southern audiences to draw the inevitable parallels themselves.

In Birmingham, a black company also mounted major productions concerned with racial matters. M. W. Morrison’s Great Day was sweeping in its scope, and covered the history of the Negro from 4500 B.C. to the present. With their production of Swamp Mud, by Harold Courlander, a play about a black man’s futile attempt to escape from a chain gang, they caught the attention of the white press; the Birmingham Weekly found the lead actor, Russel Veal, “so effective, his every emotion, his every outcry of pain and distress seemed to be your own.” But such efforts were ultimately too costly for Southern-based companies. The Birmingham unit lost its funding within a year, during the first round of budget cuts; and most companies in the region, unwilling to jeopardize their continued survival, offered more traditional, hence safer, dramatic fare.

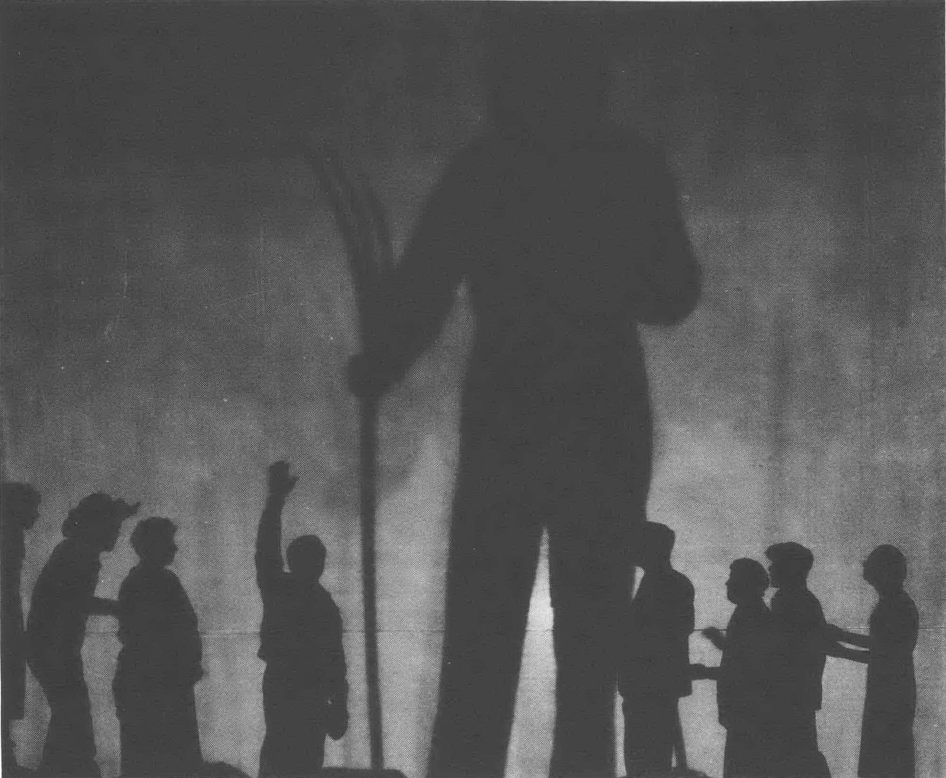

Such conservatism was not due to lack of support from the Project’s Washington-based directors who encouraged various Southern units to produce factual dramas about their region. According to Hallie Flanagan, the South offered “rich dramatic material in the variety of peoples, the historical development, the contrasts between a rural civilization and a growing industrialization.” And John McGee, who had been head of the Federal Theatre in the South, was convinced that it would make an ideal subject for a “living newspaper,” a new dramatic form created by the FTP. The living newspaper was actually a documentary with a clear editorial slant that informed the audience of the size, nature, and origin of a social problem, then called for specific action to solve it. Projections, masks, spotlights, loudspeakers, ramps, and characters in the audience were some of the devices used to bring the facts to the audience in unforgettable fashion.

The New York living newspaper unit had, in fact, researched and drafted a factual drama titled The South. But the play’s controversial subjects, which included tenant farming, organized labor, the anti-lynch law, the TVA, Huey Long, and Angelo Herndon, promised to be too offensive to the powerful Southern block of Congressmen and state WPA officials. The drama never made it to the stage. Some of the ideas in this draft were adapted to later living newspapers. The problems of tenant-farming and farming in general were exposed in Triple- A Plowed Under. The Huey Long and Angelo Herndon scenes were included in 1935, a review of that year’s events, and TVA became the focus of the second act of Power, a play about public ownership of utilities. None of these living newspapers ever played in the South, however, despite their focus on Southern issues and events.

A living newspaper had been planned on the growth of Southern steel mills, but it ended up as a fictionalized social drama, Altars of Steel, by Southerner Thomas Hall-Rogers. It dramatized the effects of absentee ownership, labor organizing, and ruthless price cutting. In the play a small, Southern mill is bought by United Steel, and immediately both labor and capital seek unfair advantage over each other. The two major characters — the former mill owner and a labor organizer — die during a riot at the plant, and nineteen workers perish in an open-hearth explosion. The play caused a tremendous controversy in Atlanta where it opened, possibly because the author was so evenhanded in his depiction of the conflict. Columnists used the play as a focal point in blaming or praising general changes in society. The Atlanta Georgian summarized the debate, which continued throughout the week-long run of the play: “The memory which should linger is... the need of economic freedom for the South and its development of its own teeming resources.”

Another attempt at a Southern living newspaper was King Cotton, written by Betty Smith with the assistance of three other writers/researchers: Robert Finch (her husband), William Perry and Clemon White. Smith was part of the Frederick Koch — Paul Green circle of dramatists at the University of North Carolina, and much of the play reflects their interest in tragic folk drama. Thus, the problem of a one-crop economy is seen primarily in human terms. The factual material on the condition of the sharecropping system is interspersed with dramatic moments in the life of one family, the Britts.

Like the other WPA living newspapers, King Cotton is heavily documented with much of the material — the case histories and statistics — footnoted. Mr. Blackboard, a personification of the loudspeaker used in most other living newspapers, supplies this information, thereby generalizing the particular dramatic moment. The audience simultaneously learns the facts and witnesses their particular effect; this technique forces the public to focus on both a particular problem and its causes.

Unfortunately, the Federal Theatre Project was killed before it could produce King Cotton. What its reception and effect might have been can only be speculation.

In the following scene of King Cotton, a so-called “expert” testifies before a Senate committee. In later scenes, he travels to the South to learn more about the problems of cotton farming, and talks “to mill hands, mill owners and social workers.” By witnessing what happens to the Britt family during one year, he learns the economics of the cotton industry — the sharecropping, the marketing, the mill, the company store — and its effect upon the people. He returns to the Senate with recommendations about controlled production, crop diversification, working conditions and education, among others. In the typical up-beat fashion of the living newspapers, the play ends with the Senators sitting down to write a bill, vowing “we be not adjourned until it is finished.”

King Cotton

Loudspeaker: The Living Newspaper presents: “King Cotton.”

(Front curtains open and the projection flies back to a screen upstage center. The title words grow smaller and fade out, leaving full screen to shots of cotton pickers.)

Over a vast realm from Virginia to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains, cotton is king. In one year, he has stored in his coffers more than two billion dollars or almost half the total amount of money now in circulation in the United States in that year. King Cotton employs thirteen million persons to till his fields and to care for those who till them. He has hundreds of thousands more laboring in his mills. Oh yes indeed! Cotton is king in the South!

(Projection dissolves to girls working at spinners in a cotton mill.)

But of late there are signs that the king is sick; that he has become a senile old tyrant; that his subjects live in abject slavery under his rule. The United States government has been gravely concerned about him. Let us go down to Washington and see for ourselves.

(Projection fades out.)

SCENE ONE: A SENATE COMMITTEE MEETING

(The Projection has been raised out of the way and lights come up on the platform upstage center, where the clerk and six men dressed in conventional stage senator’s costumes are seated about a long table above which hangs a blackboard. The senators are large and impressive. They wear wing collars and puffed-up black satin cravats, cutaway coats and striped trousers. Each wears a mask, half again as large as life-size. The masks are caricatures of Senators Smith, Thomas, Bankhead, Pope, Ellender and McNary. Each senator speaks with an accent indicative of the section of the country which he represents.)

Smith Mask: (Rising) Let’s get down to cases. What I am driving at as chairman of the Agricultural Committee of the United States Senate is not to have this annual grouch every year, but to establish a permanent program, a permanent law of equity and justice and fairness to the farmer so that he can go home and not be scared to death that God will be good to him. We have got into the most infernal paradox in the world. The farmers pray God for droughts and disasters in order to be prosperous, and everytime there comes a good season, they all go to the poorhouse. That is a hell of a note, isn’t it?

McNary Mask: It is, Senator Smith. But what would you have us do?

Smith Mask: I would first have us all become acquainted with the problem, Senator McNary. That is why I have called in the aid of a research expert. He has made a study of the problems of the South and if there is no objection, we will hear from him now.

(He looks for an objection.)

There being none, clerk, will you call Mr. Elbert Q. Expert in?

(Clerk rises and exits up left, returning almost immediately. Lights come up on Mr. Elbert Q. Expert who enters from up left on stage level.)

Mr. Expert: Very well, gentlemen. I have made an extensive study of the South. Indeed, I presented a doctoral dissertation on education in that region. If you ask me to state my conclusions briefly —

(Spatter of applause from the senators at the word, “briefly. ’’)

I should allege that the chief thing wrong with the South is its lack of proper educational facilities.

(Smith spreads his two hands over his mask in a gesture of weariness. Other senators wag their heads from side to side in a rhythmic gesture of weariness.)

If we could educate the South to the North’s standard of living, we would have solved the problem: for once having seen a better way, the Southerner would not be content with a poorer.

Smith Mask: (Sorrowfully) I’m afraid it is not as simple as that, Sir.

(Mr. Expert smiles with superiority.)

McNary Mask: (Sotto voce) I do not like his smirk of academic superiority.

Mr. Expert: It is simple, Senator. If I had a blackboard, I think I could demonstrate —

(Blackboard lights up with a projection of a caricature of a bookworm at his desk. He is in shirt sleeves and wears a green eyeshade. Lamp burns on his desk and next to it is an oil can labeled “midnight. ” Huge coffee pot is on desk next to a paper bag of sandwiches. Books are everywhere: in piles on the desk, on the floor, in his lamp and he is even sitting on some. A voice is heard via the loudspeaker behind the blackboard.

Mr. Blackboard: (Testily) Speak up! Ask for what you want. Don’t say “if’ and “and.” Holler for a blackboard and pound your fist on the table and you’ll get it. Just holler for things. We got lots of people on the project. Get you anything you need. I’m Mr. Blackboard.

Clerk: A while ago, you were the loudspeaker. I don’t like the idea of calling you Mr. Blackboard now.

Mr. Blackboard: If you don’t like it, you can call me Bee Bee for short.

Smith Mask: Mr. Blackboard is inclined to look down on our meetings a little, but he’s willing to straighten us out sometimes on the facts.

Mr. Blackboard: Thank you.

(Blackboard light goes out. Mr. Expert steps toward the platform and continues.)

Mr. Expert: Let us look at library figures.

Senators: Figures? (They groan.)

Mr. Expert: In ten cotton states there are 347 libraries; in the whole United States, 6,235. (Pause) Come on, Mr. Blackboard — I mean Bee Bee. Do your stuff.

(Blackboard lights with a projection showing a small library building labeled “Cotton States” and 347; a proportionately larger building, labeled “United States”and 6,235.)

Mr. Blackboard: There are your figures, Mr. Expert. Hey Senators! How do you like it this way?

(Projections on blackboard changes to three and two-thirds large books labeled “United States, ” and one and one-tenth books labeled “Cotton States.”)

The average person in the United States borrows 3.67 books per year from his library. The average person in the South borrows only 1.1 books per year.

(Blackboard blacks out.)

Mr. Expert: The figures clearly show—

Mr. Blackboard: (Lighting up) Say! How am I doing, Elbert?

Mr. Expert: Fine, Bee Bee. Fine!

(Blackboard blacks out.)

These figures clearly show, Gentlemen, that the South is not well informed. Now the average sharecropper—

(There is a small disturbance. At right, a spot picks up Hubert Britt, a grizzled and middle-aged farmer. He is hard-pressed and desperate, and inclined to be resentful. He is very likeable however. He hurries in angrily.)

Britt: Just a minute!

Mr. Expert: (To the senators) Pardon me. This is something I did not foresee. (Sympathetically to Britt) What is the trouble, Sir?

Britt: I heard what the blackboard said and we ain’t a-goin’ to let you spread lies about us folks down here in Dixie. If you want to tell these politicians about us, tell em the truth.

Mr. Expert: Exactly. (To senators) As I was saying, the South is backward In the United States as a whole—

(Projected on blackboard: in a border made by the outlines of the map of the US are four cartoons of illiterate-looking men holding books upside down on their laps and cleaning their fingernails with pen points. One man is black, three white.)

—only four people out of every hundred are illiterate. But in the South-

Mr. Blackboard: Here you are.

(Projection changes to map of US with all but the ten cotton states blacked out. In them, ten cartoons, seven black and three white of identical illiterates.)

Ten out of every hundred are illiterate among the subjects of King Cotton.

Britt: Cotton is king all right. Like them old-timers in Egypt who made men carry big stones for years an’ years so they could have a tomb built where –

McNary Mask: (Rising) Mr. Chairman, I move that the sergeant-at-arms be directed to eject this disturbance.

Smith Mask: One moment, if the gentleman from Oregon please.

(Other senators lean forward in attitude of debate. A monotonous oratorical sound arises.)

Mr. Expert: (Pounds the table and shouts) Silence!

(Senators lean back and rigid silence envelops them. Mr. Expert looks at his fist, smiles happily at Blackboard.)

It worked! (To Britt) I know the South is bad off. Didn’t I write a hundred page thesis on the subject? But you, as a farmer, should not speak so harshly of the greatest crop of the South, cotton. Cotton is your benefactor. Without cotton, the South would starve.

Britt: I hitchhiked all the way up here to tell you stuff-shirts and bloated faces that that’s exactly what we are a-doin’. Starvin’! (To Mr. Expert.) An’ if you didn’t keep your nose poked in books all the time, you’d know we’re starvin’!

Mr. Expert: Who are you?

Britt: I’ m Hubert Britt. I’m one of ten million that chop cotton. Since you know so much, you up and tell the senators how much I make for workin’ all year from sun-up to first dark. Just tell em.

Mr. Expert: Why. . . I . . . don’t know. How much do you make?

Britt: Last year I got eight cents a pound. I made nine bales.

Mr. Expert: Ah! How many pounds in a bale?

Britt: (Disgusted) Five hundred. Mr. Expert: Let’s see. Five hundred times eight cents. That’s forty dollars. Nine bales . . . hey, Bee Bee!

(On blackboard is projected 9 times 40 equals $360)

Mr. Blackboard: Three hundred and sixty dollars, Elbert.

Mr. Expert: You mean that’s all you got for a year’s work?

Britt: Didn’t get that much. Didn’t get but half of that. I sharecrop.

Mr. Expert: You mean you share your crop?

Britt: Yeh. Got to give my landlord half of everythin’ I grow.

Mr. Expert: What for?

Britt: For lettin’ me use his land and furnishin’ me.

Mr. Expert: Furnishing . . .?

Britt: Say, you are dumb. All you know is what you read in books. Furnishin’ means that he gives me seed, a mule and gives me credit when I have to buy food.

Mr. Expert: Then I understand that you had free seed, a mule and supplies, a house and one hundred and eighty dollars clear at the end of the year. Doesn’t sound so bad.

Britt: I had to buy my stuff at the landlord’s store. He gave me credit. I had to settle up out of my half; out of my one hundred and eighty dollars. When I paid up, all I had left was sixty-five dollars.

Mr. Expert: Surely your case isn’t typical. Cotton brings more than eight cents a pound some years. I know that.

Mr. Blackboard: (The figure $210.00 is projected on the blackboard) At 9.4 cents per pound, cotton brought the average sharecropper S210. For a whole year’s work. This was not pay for one man’s work but of the entire sharecropper’s family.

Mr. Expert: Do the wives and children have to work too?

Britt: You bet your life. Me an’ Lally and all five of our kids got to chop cotton or old man Powers would put us off his place.

Smith Mask: So that your yearly per capita wage after you settled with your landlord and the commissary was sixty-five dollars divided by seven, or about nine dollars each for the whole year?

Britt: Yeh! Yeh, not enough to pay the doctor for the malaria our youngest died with.

Mr. Expert: I hardly think it is as bad as you say. You said, and I believe I read somewhere that the landlord usually gives you people your homes, doesn’t he?

Britt: If you can call them homes. Trouble with you is you got all you know out o’ books. Why don’t you come along with me an’ let me show you what they call a sharecropper’s house down where I come from. Before you talk so much why don’t you find out what in hell you're talkin’ about?

Mr. Expert: I'd like to go, but the Senate committee expects me to—

Smith Mask: Tut, tut! That’s a very good idea, Britt. You take him home with you. We’ll wait.

Bankhead Mask: We've been sitting up here talking about doing something for the cotton farmer for thirty years now. We won’t have finished I’m sure, before our witness returns.

Thomas Mask: One moment. Are you able to make a living?

Britt: I ain't done it.

Thomas Mask: Well, you do live.

Britt: By goin' in debt.

Thomas Mask: Would you be able to make a living if you could rent more land?

Britt: I ain’t able.

Thomas Mask: Have you ever thought about moving to some other territory where you might be able?

Britt: It takes money to move.

Thomas Mask; You don’t see much future as a farmer, then?

Britt: I don’t see none. And you won’t neither when this feller comes back and tells y'all what he's seen. Come on, Mister.

(The spot follows them out, up right, then dims.)

Smith Mask: Well! Now maybe, we are getting somewhere.

(Blackout.)

Tags

John O'Connor

John O ’Connor is on the staff of the Research Center for the Federal Theatre Project at George Mason Univ. in Fairfax, Va, which has the nation’s largest collection of FTP material. (1978)