Klan Kash & Karry: “No Comment”

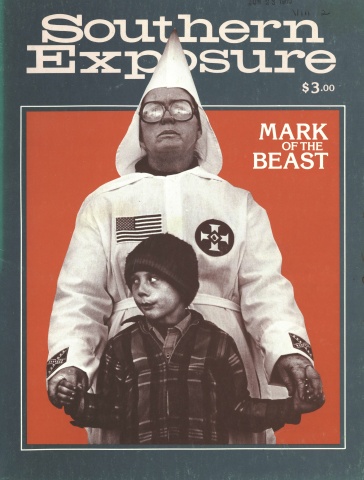

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

The black mayor of New Orleans didn’t know when he became honorary chairman of the France-Louisiana Festival that a national Ku Klux Klan leader would publish the festival’s monthly newspaper. “He was completely unaware of it until this moment,” said Jay Handleman, press secretary to Mayor Ernest Morial. Nor did the mayor know that when his administration agreed to give the festival free rent in the International Trade Mart building that the same Klan wizard would sell advertising for the newspaper Festival from those offices.

The first edition sold more than $12,000 in ad space, according to the Festival rate card. Under his agreement with festival officials the Klan leader received 85 percent of the ad sales revenue and paid publishing costs. The festival got 15 percent.

“Published by E.C. Promotions, 339 ITM Bldg.,” reads a subscription ad in the initial edition of the newspaper last July. Only a handful of people — perhaps only two — knew that “E.C.” stood for Elbert Claude, the name given at birth to the man now known as Bill Wilkinson, 37, Imperial Wizard of the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. The “339 ITM Bldg.” address was the suite of plush offices to which the city gave Wilkinson access while he conducted his business for Festival. Wilkinson was one of the two who obviously knew. Another was a former Klan wizard and Klan editor named Jerry Dutton, a member of the Festival board.

Those close to Wilkinson in the past say E.C. Promotions was a Klan front name he used to raise money for his Denham Springs, Louisiana, KKK operation. Wilkinson himself will not discuss E.C. Promotions or his relationship with Festival.

“I have no comment about that,” he told reporters.

Dr. Donald Landry, a well-known New Orleans area dentist and active civic leader, is chairman of the France- Louisiana Festival. He told reporters he had no idea that the man introduced to him as “E.C.” was actually Bill Wilkinson, the Klan leader. Sometime later, Landry said, he saw Wilkinson on television during a Klan march. “I ended the relationship at once,” he said. As Morial and Landry were unaware of the Klan connection to the festival, so were Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards and Gilbert Bochet, consul-general of France, who, with Morial, were listed in Festival as honorary co-chairmen.

The E.C. Promotions deal with the France-Louisiana Festival is one example of the diverse ways leaders of the “new” Klan generate funds to sustain their competing and growing organizations. What Wilkinson had in mind there seems clear. More clouded is a recent transfer he made of his property — including the site where his new Klan headquarters is under construction — to something called the Universal Life Church of Modesto, California. Universal Life is known as a mail-order church, granting pastories by mail.

The transfer was recorded at the Livingston Parish courthouse January 2, 1980. On its face it appears to be a search for a tax shelter., but it could be that the Klan leader thinks he is protecting himself against a lawsuit or some other future effort to take his property. He was smilingly evasive when a reporter told him the transfer had been discovered by an investigative news team.

“It could release me from any encumbrances that could influence any decision I might make in the future,” Wilkinson said of the transfer. “It could release me from having any, let’s say, financial conflicts with my beliefs ... a wide range of things that could get very complicated.”

His deal with the France-Louisiana Festival is much easier to understand.

Landry, the France-Louisiana Festival chairman, readily explained to reporters how Wilkinson got into the deal. Landry had met an antique dealer named Gerald Dutton — the same Jerry Dutton, it develops, who had been David Duke’s Klan Grand Wizard before leaving and becoming editor of Wilkinson’s newspaper, The Klansman. The festival committee Landry chaired was not doing well financially. Dutton, says Landry, offered to help. He brought in “E.C. Wilkinson” with the suggestion that “E.C. Promotions” sell ads and publish a monthly bi-lingual festival newspaper. Landry thought 15 percent would be better than nothing, so he took the deal, not knowing Dutton’s past. He also put Jerry Dutton on the festival board.

The first edition went over big, with plenty of advertising. But after the first issue, the ads dropped substantially. Then Landry saw “E.C.” involved in a Ku Klux Klan conflict — but a TV newsman said his name was “Bill” Wilkinson. Landry was startled. As a Catholic, he felt the Klan was an affront to what he believed in. “I hate the Klan,” he told the Nashville Tennessean. “I spit on the Klan.”

Wilkinson, who had put out two editions of the newspaper, gave up his role in the publication. Dutton, who was involved in typesetting, continued to lay the paper out and set the type. He still is doing so, and Landry has had a hard time believing that his festival board member, Gerald Dutton, is Jerry Dutton, a former Klan Wizard and Klan newspaper editor.

Dutton was active in protests against the civil-rights movement when he was a member of the far-right National States Rights Party in Birmingham in the early 1960s. Four times during the turbulent ’60s he was arrested and convicted for engaging in protest actions against blacks, including a resisting arrest charge. He was sentenced to two years — four separate 180-day sentences. Dutton spent several years on the West Coast, then moved to New Orleans in 1976 at the invitation of an old friend from his Birmingham days, anti-Semitic publisher James K. Warner, who was then “national information director” for Duke’s Klan.

After Dutton split with Duke in 1976, Dutton says, he took a copy of Duke’s mailing list to Wilkinson and began serving as editor of Wilkinson’s Klan paper. Dutton appeared with Wilkinson on the platform at the Invisible Empire’s “Fire Andrew Young” rally in Plains, Georgia, in 1977. A sports car rammed the speaker’s platform and sent them sprawling.

He has recently used a Metairie post office box number, 8862, to mail out a sheet entitled, “The Truth About David Duke.” When E.C. Promotions gave the France-Louisiana Festival board an address, it was Box 8862, Metairie. Despite his past activism, Dutton has managed to keep his Klan related ties concealed — at least from Landry and others associated with the festival. Landry, after accepting the idea for the newspaper, asked the mayor’s office for rent-free space and got it at the ITM building. “I simply will not believe that Jerry is involved in all that.”

When Wilkinson and his E.C. Promotions were severed from the festival, Landry asked Dutton to find him another person to sell ads. Dutton did so. He also continues to do the layout and typesetting of Festival at his own company, Image Typesetters, located in Metairie.

Landry, Mayor Morial, Governor Edwards and French Consul Bochet had similar responses when asked about their knowledge of Dutton’s Klan past, Wilkinson’s identity and the two men’s relationship.

“Somebody wrote me a letter and asked me to serve as honorary chairman and I said I would,” Edwards said. “I’m totally unaware of any of the rest of it. There are good Cajuns who may be Klansmen, but there are no good Klansmen who are Cajuns,” he added, referring to the French- American ethnic background of many citizens of his state.

Bochet said that if the Klan tie proved to be an embarrassment, “the French government will have to withdraw” from the festival. “I will have to investigate,” he said.

Dutton was highly agitated when he learned that the press had learned the story of E.C. Promotions and his ties with Wilkinson. He would not discuss it with reporters who telephoned. His wife said he would not answer any questions asked by reporters.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.