This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 4, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Occasionally, in roadside cafes below the Mason Dixon line, diners find their plates laid on paper placemats decorated with humorously drawn maps depicting the “United States of Dixie.” The maps are drawn grossly out of proportion, with the Southern states filling up most of the area and a small space at the top devoted to “assorted Nawthern states.”

There is a macabre irony about these maps when one compares them to the history and now the resurgence of capital punishment in America. Proportionately, the role of the Southern states in the grisly practice of legal killing dominates the map much like the joke printed on the placemats. Though all 48 of the continental states have at various times used the death penalty, 12 states in the South have performed more than 60 percent of all government-sanctioned executions. Of all the death row inmates in the United States today, 85 percent are in those same 12 states.

Barring the unforeseen emergence of another Gary Gilmore somewhere else, it is almost certain that the next execution will happen in the deep South. The prisoner nearest the death chamber today is John Spenkelink of Florida; his death warrant is signed and only the persistence of his attorneys is keeping him alive. (See separate articles in this section on Spenkelink and inmate Johnny Harris of Alabama.) Other Florida inmates behind Spenkelink have also exhausted all their appeals, and there are inmates in Georgia and Texas who are similarly nearing the end.

These situations give a sense of urgency to the activities of those fighting the death penalty. They thought they had beaten capital punishment in 1972 when the lives of about 600 condemned persons were spared by a Supreme Court decision. But, in a 1976 decision, the Court laid new guidelines under which the death penalty could be imposed. Six months later Gilmore was dead, the first to be executed in this country since 1967.

THE BATTLE AGAINST EXECUTION

Death penalty opponents are mounting a three-pronged attack: trying to avoid death sentences at the trial level; seeking delays and reversals of death sentences at the appelate level; attempting to change public opinion and the law by lobbying legislatures, governors and the President and through the use of rallies, demonstrations, vigils and media coverage. Most of the activity is happening right in the South.

Millard Farmer, the Atlanta lawyer who made a national reputation when he defended, in the courts and on the streets, the young black men who came to be known as the Dawson Five, puts a cunning twist on an old cliche when he refers to the South as the Death Belt, and to the small rural counties of south Georgia as the buckle on that belt. Farmer’s clients — typical of capital defendants — are almost always poor, uneducated and black.

Black people in general must be considered something of experts on capital punishment in this country, for they have had more than their share of first-hand experience with it, in the North as well as in the South. Of all persons executed since the 1930s, when officials began to keep reliable records, 53.5 percent have been black. Almost 90 percent of those executed for rape have been black, 76 percent of those executed for robbery, 49 percent for murder, 100 percent for burglary. Blacks have accounted for only about 10 percent of the total population during this period.

Clarence Darrow, in a 1924 debate in New York City, commented on the relationship between high rates both for homicide and executions in the South. "Why?” he said. “Well, it is an afternoon’s pleasure to kill a Negro — that is about all.” Southern society has passed the point where white men could kill blacks with impunity, so that part of Darrow’s theory is outdated now. But the faces peering through the cell doors on death row remain disproportionately black; it may not be easier for a judge to pronounce a death sentence on a black man, but it does happen more frequently. Discrimination in the application of the death penalty was supposed to have ended with the Supreme Court decision in 1972 in the case of Furman v. Georgia. The Court said that capital punishment as then practiced amounted to a lottery conducted by judges, juries and prosecutors in determining who actually died. The laws then in force allowed juries to give the death penalty for a number of crimes, and to decide each case arbitrarily. In practice, that discretion meant that juries frequently gave death sentences to minority and poor defendants for crimes that might earn lesser sentences for more privileged whites.

Executions had already declined from a high of 199 in 1935 to a trickle in the mid-’60s when Colorado gassed Luis Jose Monge to death in 1967. He was the last to die until Gilmore 10 years later in Utah, but between 1967 and 1972 juries continued to give death sentences. By the time Furman was decided, more than 600 condemned persons were waiting on death rows.

After Furman, however, legislatures thought they could meet the standards set in that decision with the implementation of new laws which either took discretion completely out of the system or which put into play a two-part procedure: first, the defendant’s guilt or innocence is determined in one hearing, and then the punishment — death or a lesser sentence — is determined in a second hearing in which both aggravating and mitigating circumstances of the crime are considered.

Between 1972 and 1976, 35 states enacted new death penalty laws, and the death row total climbed up to more than 500. Finally, on July 2, 1976, the Supreme Court spoke again, upholding, in the case of Gregg v. Georgia, death sentences imposed under a law which allowed the guided discretion of a two-part trial. The Court also upheld similar laws in Texas and Florida, and the country was back in the execution business.

At the same time, however, the Court decided Woodson v. North Carolina and a similar Louisiana case and voided the death sentences imposed in those states under laws which allowed no discretion but made death mandatory upon conviction for certain categories of crime. Thanks to these and subsequent rulings, 391 prisoners had their lives spared. One hundred and one other death sentences were commuted in Ohio as the result of the Bell and Lockett decisions before the Supreme Court in July, 1978.

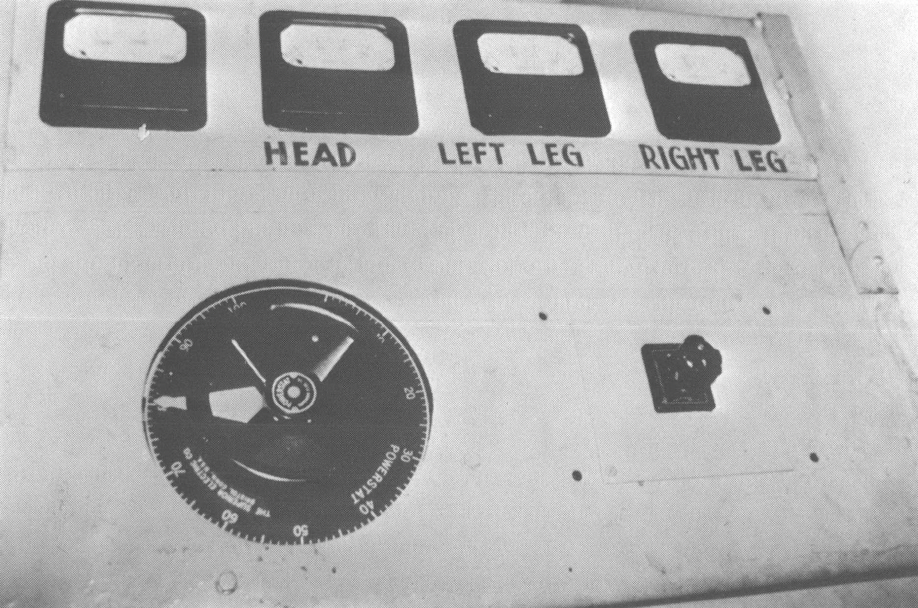

But the death row population continues to climb. The Southern Death Penalty Information Center reports that 395 inmates are condemned to die under laws which the Supreme Court has already upheld. Of the 395, all but 50 were condemned in 12 Southern states. Florida has 113, Georgia 72, Texas 74 and Alabama 36. For some of the condemned, time is running out. Many states are testing their gas chambers and electric chairs and hiring executioners again.

There is a chance, however, that the next inmates to die won’t do so by gas or electricity at all, but by the scientifically superior method of lethal injection.

A hanging takes an average of eight to 10 minutes to complete. The head must be hooded because the knot often rips open the side of the face. Frequently, the victim swings until he has strangled to death. There are recorded instances in which strong prison guards grabbed the condemned man’s legs as he hung, pulling downward on them to speed the process along.

Shooting also disfigures, and may not kill instantly.

Gas takes a long time and witnesses don’t like to watch it because they can see the contortions of the body as it strains against the straps trying to escape. The hands open and close for a very long time after the pellets have dropped into the acid.

Electrocution produces a “two-minute death dance’’ as the average eight cycles of alternately 2,300 and 1,000 volts are applied. Usually the witnesses are separated from the death chamber by a glass partition. This spares them the smell of burning flesh. The condemned man’s eyes are usually masked because they may come out of their sockets. Urine is inevitably released, and the body may have to be forcibly straightened to make it fit into the coffin after the execution.

All executions today are performed deep within prison walls. The object is to deter, to protect society, but the act is so brutal that it must basically be done in secret; society must be protected from the act meant to protect society.

I got a score to settle with one of the lawyers of the land, with who, with one of the lawyers of the land, & that’s not nearly all because I also have a score to settle with that robe man Tricked Why, because I paid my money to get a life sentence, which wasn’t so damn funny—Tricked I mean, I could have fought that case by myself, the charge didn’t carry but a life, I should have kept my money instead of paying someone else Tricked Embezzled Robbed Tricked There is nothing you can say to make me believe that I was not tricked...by the lawyer of the land & the robe man, when their combined actions & deeds amounted to life Tricked...but not buried...buried only with time.

— Erroll E. Bernard

Camp J

Angola, La.

Texas and Oklahoma have already passed laws making the injection of fast-acting barbiturates the legal means for killing in those states. Florida and Tennessee have been considering similar laws. An inmate in Alabama who, like Gary Gilmore, has insisted that he wants to die rather than live his life in prison, finally agreed to let lawyers appeal his case so he could lobby — by mail — for lethal injection in his state. The inmate, John Evans, who killed a Mobile pawnbroker in a robbery while the victim’s small daughters watched, argues that electrocution cooks the internal organs, leaving them useless for medical research or for donations to people who need transplants. Evans says he wants the dignity of knowing that his death might help someone else.

Injections are also said to be more merciful and less repugnant, but some opponents fear this might create a dangerous climate in which euthanasia in general becomes less objectionable, leading perhaps to the day when the elderly and the handicapped are also “done away with,” humanely and efficiently. Says Jim Castelli, a writer for the National Catholic News Service, "Execution by lethal injection is the modern, American way — fast, antiseptic, medicinal, painless. Lethal injection does for execution what the neutron bomb does for war — it makes the unthinkable more thinkable.”

DEATH: AN EITHER/OR CHOICE

Why is the unthinkable spectre of executions so popular with the American public today? Anthropologist Colin Turnbull, in a recent study of death rows as societies, says he was told by a man who had effectively lobbied to restore the death penalty in his state, “We don’t know what else to do, and we have to do something.” The death penalty is a ritual sacrifice of the type made when there is fear, Turnbull said. “When man recognizes his impotence, he falls back on the unknown.” Ritual elements help society cope with murder and death: inmates are fed last meals, given last rites, made to walk the “last mile,” confronted with — in some states — a hooded executioner, formally read the death warrant and then, before a congregation of witnesses, put to death.

There is desperation today, Turnbull says. People want to be safe. They are afraid of violent crime and violent criminals, men like John Evans who come into their homes and businesses and take their property and their lives. Such men are reduced by the legal system to non-persons, to animals. They can be killed.

Once the humanity of the inmates has been removed, it is simple enough to go on to the argument capital punishment supporters make about the economics of feeding, clothing and supervising a dangerous criminal for the rest of his life. Since most felony murders are committed by young men, life imprisonment could be very expensive indeed. But the costs of execution can also be very high. Appeals for condemned men are hard-fought and may take years, so “economical,” speedy executions are out of the question. The costs of operating the special segregation system used for condemned men also run very high.

There is strong evidence that many condemned inmates can be successfully rehabilitated. Reprieved prisoners frequently become models for the rest of the prison population. Some wardens believe this may be because these men, confronted with their deaths, have had to look deeply within themselves. Some primitive societies require criminals to make restitution to their victims. A murder victim obviously can’t be restored to life, but his murderer could be made to support his family, thus relieving the state of burden and allowing the murderer to find self-worth.

Opponents of the death penalty cite two last irrefutable arguments against executions: there is always the possibility of executing the innocent, and the process of deciding who actually dies is still too arbitrary.

Capital punishment supporters say that the threat of imprisonment, even for life, is not enough to keep criminals from killing, and that the deterrent value of the death penalty is needed to protect society. Most opponents of the death penalty believe that there is no deterrent value. Most serious scholars agree that the studies which exist are not definitive, but indicate that if there is an effect, it is slightly more likely to encourage crime than to reduce it. Sociologists explain the phenomenon by noting that a society which officially devalues life by execution sets an example which makes life less valuable to the individual as well.

The single most widely known study, by Thorstin Sellin, compared a number of variables in death penalty states to the same variables in similar or adjacent states which did not have the death penalty. The results showed higher homicide rates in the death penalty states than in those without it. The one exception to the general trend of studies is a report by Isaac Erlich which claims that every execution has the ability to prevent seven or more additional murders. Erlich’s study is important because it appeared in 1975 when public debate over the value of capital punishment was intense; it was cited by the Solicitor General of the United States as a reason why the Supreme Court should uphold the death penalty in Gregg v. Georgia.

Other capital punishment scholars were quick to attack Erlich’s study, criticizing both his data and his technique. The only safe statement which can be made today about the deterrent value of the death penalty is that it is unproven; it remains a matter of personal speculation.

Similarly, the moral rightness or wrongness of capital punishment is usually decided by an individual’s own conscience. Clarence Darrow said it this way: “There is just one thing in all this question. It is a question of how you feel, that is all. It is all inside of you. If you love the thought of somebody being killed, why, you are for it. If you hate the thought of somebody being killed, you are against it.”

Supporters of the death penalty insist that it is a moral duty to execute murderers. But they can only recite the Biblical injunction of “an eye for an eye.” That message was written in a culture and a time far removed from our own, and most of the mainline churches today are strongly opposed to capital punishment.

Nevertheless, public opinion polls that once showed higher support in the fundamentalist South than elsewhere for the death penalty now show consistent support in all areas of the country, among all age levels and social classes. Blacks are just about the only group left which express a majority sentiment against executions, and even that opposition is not as pronounced as it once was. The shift in opinion came suddenly. As short a time ago as 1966, a Gallup poll found a plurality of 47 to 42 percent opposed to the death penalty. By the spring of 1976, however, another Gallup poll found the death penalty back in favor: 65 percent for, 28 percent against.

Groups like the ACLU and the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons are working hard to reverse support for executions, but the increasingly conservative, frightened and vindictive mood of the nation makes the going slow and difficult. Increased attention is being given to fight the death penalty at the trial level, and the two organizations leading the way are the Southern Poverty Law Center of Montgomery and Millard Farmer’s Team Defense Project of Atlanta. Both launch all-out attacks on the prosecutor’s case. Both use extensive pre-trial investigation, motions, expert witnesses, jury selection and constant psychological warfare during a trial.

The Southern Prisoners’ Defense Committee, headquartered in New Orleans, supplies materials and information which help a private defense attorney meet the well-equipped state prosecutor on a more equal basis. Once a case gets to the appellate level, it may end up in the hands of the Legal Defense Fund, the New York-based group once headed by Thurgood Marshall. LDF attempts to keep clients alive, waiting for the day when public opinion may change again on the death penalty. The Supreme Court has said that the definition of “cruel and unusual punishment’’ may be determined by “evolving standards of decency.” It was once common to burn witches, to brand adulterers, to whip thieves. Those practices eventually became repugnant and ended. In time, the United States may join Canada, Great Britain, New Zealand and the Scandinavian nations in abolishing executions.

Meanwhile, the death rows continue to swell. There may be 800 persons awaiting execution by 1980.

Tags

Randall Williams

Randall Williams is a fugitive staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is currently living and working in north Georgia, where he is guiding the start-up of two weekly newspapers, the Chickamauga Journal and the Lafayette Gazette. (1980)

Randall Williams is an Alabama native, a journalist and former editor of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s newsletter. He is now on the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1978)