This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 3/4, "No More Moanin'." Find more from that issue here.

Tom Lowry composed the “Little David Blues” in his head, and that's the only place he thought the words and tune were. He was amazed to learn from us that someone had written down the song during the Davidson-Wilder strike, and that it was published in American Folksongs of Protest. No one even bothered to tell him.

We had found out about Tom from some friendly people in the Davidson community grocery store. They were looking over the songs we showed them, explaining verses to us, and someone said, “Why Tom Lowry, he lives right up here in Roanoke!”

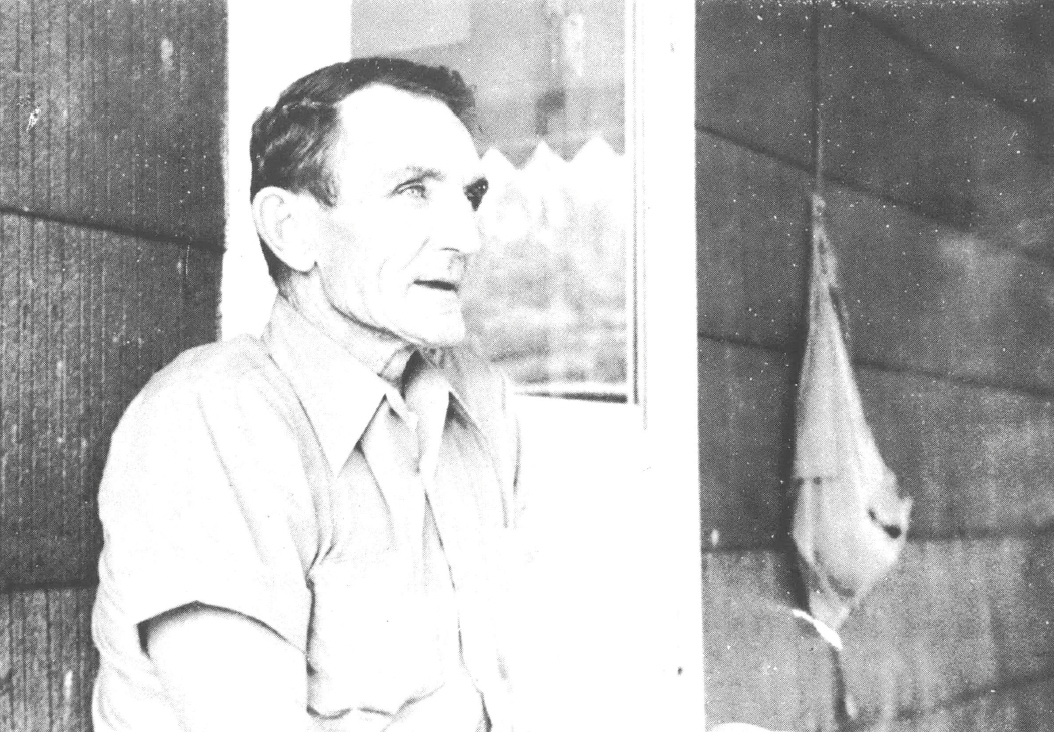

One late summer morning Fran Ansley, Florence Reece and Brenda Bell sat on Tom’s side porch and talked with him about his song and about coal mining. Florence also wrote a song during a mining strike—she was in the thick of the Harlan battles with her husband Sam and young family when she wrote “Which Side Are You On.” Tom and Florence had never met. Here are some excerpts from our conversation together.

Tom: I hadn’t thought of that song, hadn’t thought of that holler. ... I hadn’t thought of none of that in years!

Fran: When we first came over in Fentress County, we didn’t know anybody. We knew your song—that’s what got us off on this whole wild goose chase. We wanted to hear the story of the strike.

Tom: You mean that song got you people started on this?

Florence: Look what you done and didn’t know it. You done a lot of good and didn’t know it. I’m so proud! I’m glad they brought it back to memory. Sing it for us!

Tom: I swear, I never would have thought of that no more! (Laughing.) I don’t know if I can sing it, but I’ll try. You know, that takes me a way back, buddy. I can just see me setting on that old big front porch over there. . .let’s see. . .Little Cowell. . . .

(There is a pause, while Tom studies his song, talking to himself, trying to get up his nerve to sing for us. Then he starts singing, hesitantly at first, the tune wavering, but then getting steadily stronger. He chuckles at the words as he sings, and we laugh and sing along some. He’s good.)

Tom: Now I don’t know if that’s any way near the way I used to try to sing that.

Brenda: Tell us how you came to write the song.

Tom: To tell the truth now, I was running around there. If I hadn’t married when I did I don’t know what I would have done. I hate to admit it, but I was a little bit on the mean side. I’d been mistreated now; I wasn’t getting along with my stepdad when I left over there. I left home because I knew I’d kill him or he’d kill me one. So, I got to drinking and just about anything to do, I’d do. I didn’t care, it didn’t make no difference to me. I got to feeling like I didn’t have no friends in the world. Everybody seemed like they were agin me, which they wasn’t—I can see that now.

I don’t know, you’d have to know the situation of that song before you know what it was. It all had to do with the circumstances that come up around me. The strike started it. The little fellow in there had been like a daddy to me. I mostly made that song about that one man. That was Little David Cowell. He was a little bitty fellow and they brought him in there in that strike as a bookkeeper. “Oh gee, oh golly,”—that was about as rough a language as I ever heard from him. One of the finest men I ever got to know in my life.

Well, of course, the miners worked hard. Some of them, like when you “go through the office one by one,” I’ve heard many a man go through there after two dollars in scrip, they’d ask for two dollars and Cowell’d look at what they’d done that day. You see, when you load your turn of coal that day it comes by telephone from the mine and they call it down to the office before the miner comes in. Cowell’d say, “Gee golly.” Maybe you loaded so much and you’d ask for two dollars and he’d say, “Oh gee, can’t have two, just make it one.”

But Mr. Cowell, see, he went on and done different things that I didn’t like at the time. He was against what I was believing—I thought he was anyway. I thought he was agin the Mine Workers, agin everybody that was striking, which he wasn’t. He worked down there for that company, and he lived on a dime’s worth of cheese and crackers, that was all a person could eat. He worked for so little, well, that’s what he lived on. It just come out of the top of my head, I just started remembering it. I don’t know, I hadn’t thought no more about it since then.

I was thought very little of, myself, now I’ll just tell you. My wife, even she thought I was a regular smart aleck. Even in that song, now, I was trying to do my bit, I guess. I was going to tell them how I felt, anyway. I didn’t just tell it in that song, I’d tell it to anybody who would listen to me. I was a hundred percent for the union.

Florence: When you was writing that song, you was organizing. You should have written down those songs, and you should now. Why don’t you just study when you’re by yourself? Just think, think, think—and when you think, write it down. It’d be good for the people.

Tom: As Snuffy Smith says, “When your schoolhouse is as weak as I am, you don’t write too much.” You see, I didn’t get through the third grade.

Florence: Well, we didn’t—my husband didn’t either.

Tom: You see, back then, when a boy got big enough, and come out of a big family, he’d go to work. Of course, I did, too. I had two full sisters and they was twin, and me, and there’s eight more.

Florence: Coal miners, they raise big families. And when their sons would get up, they’d take them in the mines with them to help them load up coal to feed their families. And as soon as they’d get old enough, they’d get married, and it’d start revolving all over.

Tom: Back then it was nothing strange for a twelve-year-old boy to be working in the mines. So they’d do that, and they growed up like anything else—like a boy raised on the farm out here.

Of course, I did a lot of other things besides mining, but that’s what I knowed. I worked at Oak Ridge, I worked on construction work, I drove a school bus for some time, I worked for the state highway department and the county. Just little jobs in between. But until I got crippled in the mine over here, I’d go right back in the coal mines.

But that strike and all that, that was a rough deal. That song I wrote, I didn’t call it a song. I didn’t call it anything. As I said, mine was mostly about old man David Cowell and how he’d turn people down. I tell you what, it’s pitiful, you take a man that goes in the coal mines and works real hard all day working in that—I’ve seen men in water up to their knees. They couldn't get the company to furnish the pumps to pump it out, and they just walked right in there and worked all day long, buddy. Then you got in that office to ask for your scrip, and your family maybe had a little flour, a little gravy. It may sound like a lie, but I swear it’s true. My mother would take a biscuit and put sugar between the biscuit and a little chew of fat meat, and I’ve loaded 20 tons of coal on that.

Florence: I know you’re telling the truth. My daddy faced the same thing, and my husband faced the same thing. So, when coal miners get together, they know when the truth is told!

Tom: And came back home for supper and you know all there will be for supper is pinto beans and cornbread.

Florence: Exactly! I’ve told you many a time,

Brenda: That’s what we had. That’s what I raised my children on.

But here’s the thing. You know all these things, and your children face this same thing. You can tell them what will happen to them. You say, “Now, when these demonstrations come, they’ll probably ban them and say, ‘Oh, don’t get in that demonstration, ain’t going to do no good—communist’.’’ It’s no such thing. It’s people wanting a decent wage. And they’ll kill you for less than that.

Brenda: You say, Tom, we need to understand the circumstances around the strike. I wanted to ask you where did “All night long, from midnight on” come from? Did people always work night shift in the mines?

Tom: I guess where I got that “midnight on” in there. A lot of fellows would go in the mines and work all day, then they’d come out and go back to prepare for the next day. They’d work half a night. I’ve done that. I doubt at that time there was a night shift except people who fired the boilers. Very little night work, except preparing for the next day. Later on, when I worked at Horse Pound, we worked straight around the clock. Quick as one shift come off, another went on.

Brenda: There’s a verse in here about the fellow with the black moustache.

Tom: They brought him in there from Livingston. Store manager, and he got rich off them coal miners. They paid him a salary and he got a percentage. Of course, they do that a lot now. He was a big dark-skinned fellow and wore a moustache. I wrestled with him a lot, I used to way-lay him. He wore white a lot, and I’d way-lay him. See, there wasn’t nothing around there but coal dust, sulphur balls, and ashes, and I went without a shirt a lot. He’d sneak around and try to get back in the store before I could find him. I’d hide from him and I’d just run out. All I wanted to do was black up his clothes. He was all right. He was a good boy.

Brenda: He’d write down how much scrip you’d bring in?

Tom: “Writing down in the floor.” Where I got that, you see, everything back then had to be weighed. Back then you had to cut it and weigh it. Pinto beans, you’d have to weigh them. Before draw day, you’d weigh it and have it all ready. Well, they wrote down when you went in there to trade. The store manager always had a ticket book or something and he’d write that down. Of course, he wasn’t writing it down on the floor. Floor just rhymed with store.

As for the other people in the song, John Parish was the fellow Mr. Cowell started to working for. He had an old sewing machine. Seems to me like he was a notary public, or a lawyer maybe, a little jack-legged lawyer. Then during the strike, there were two brothers, E.W. and Hubert Patterson. They bought the Davidson mine and Mr. Cowell went to work for them as a bookkeeper, under a contract. And the miners struck. Then I took my spite out on him, and them others.

Now there’s other verses to it I can’t remember. There’s more to it than you’ve got. There’s some of it pretty rough! I guess it’s too rough to write down, to tell you the truth of it!

Fran: Well, I guess you all had a rough time of it! Sometimes it’s hard to understand how people could come through it.

Tom: I’ve come in, since me and Edna married, I’ve come in so tired that I’d have to lay down a while before I could take a bath. Of course, you took it in an old tub.

Florence: Yeah. Eyes so black—you couldn’t get all that coal dust out.

Tom: That’s right. And I’d work on a motor. I’ve went to work many a morning at 5 o’clock, and they’d turn the lights on at the tipple. I mean in the summer time like this weather right now, you can just guess how many hours we’d work. They’d turn the lights on to dump the last trip, and we only got the same price—it didn’t make any difference. Never heard of overtime or double time.

Florence: And no vacation with pay.

Tom: Only time I can ever remember getting off in my life back then was at Christmas. They would give you Christmas off. Didn’t have no holidays.

Florence: The men used to tell my husband, he’d tell them about they’d get so many days with pay. “Who ever heard of getting paid for not working?” He said, “If you got sense enough you’ll stand up there.” Now they’re getting it. They say now, “Sam, you know a long time ago you told me about that and I thought you was a liar.”

Tom: There’s been a lot of sacrifices for that Mine Workers.

Florence: I say there has.

Tom: I actually guess the biggest part of that started in Harlan, Kentucky.

Florence: That was something awful. They’s a man up there, and he’d just shoot them men, I don’t know how many. But finally they killed him. Said the man’s wife went over there after he was shot, and he wore a breast-flint, and said he had something on his face, and they just raised that up and spit in his face, after he was a-dying. Because he killed so many people. He was worse than Hitler, it could have been.

At first I just went to church and thought, “It’s bad, it’s bad,” until them thugs started. Then I thought, “You stand up and be counted or you’re going to be killed and your children will starve to death.” They’s one woman, they arrested her husband and put him in Harlan jail, she had little twins, and she had pellegra, you know, scaled all over and starving. They said, ‘‘Florence, don’t let her stay with you, you’ll catch that.” I said, ‘‘She got that from her table, I won’t catch it.” She took her two little girls and went to see her husband. Old John Henry Blair said, “We’ll turn you out of jail if you’ll leave the county.” “I ain’t going to leave the county,” he said, “I live here; I want to stay here and go back to work.” And he give them two little girls a dime apiece. That dirty old high sheriff.

Tom: They didn’t care about life. Now that part of that there song there, “Don’t kill that mule, you be careful with that mule, because we can’t buy that mule. We can get men, but you can’t go out here and buy a mule.” But dad-gum that man. I’ve heard the mine foreman, “If you don’t like it, bare-footed man waiting outside the door there waiting to take your job.”

Florence: Exactly! And that’s what my husband—boy, you could hear him cussing. One old superintendent said, “I hope that these miners’ kids had to gnaw the bark off the tree.” And, boy, they was a-looking for him. They said they was going to kill him. I told my husband, “Don’t you do that, it ain’t worth it, don’t do it.”

Fran: Florence, why don’t you sing your song for Tom?

Florence: Used to, I could sing, but now I can’t because I’m too old. My throat’s always grooveling. We’d always sing in church and everything, you know. See, I wrote this song in 1930; they had the Harlan strike then.

Tom: Yeah, lord, I read and heard about that.

Florence: Did you hear about “Which Side Are You On?”

Tom: No.

Florence: That’s the name of the song. Because you see, the gun thugs were coming down to help them search our house; my husband was an organizer with the United Mine Workers. And they’d put him in jail, and turned him out, and all that stuff. And he had to kindly stay out to go on organizing. And the thugs were to come, why, they would have killed him if they’d come. They’d search our house to see if we had any high-powered. I said, “Well, what are you here for?” I had a bunch of children. They said, “We’re here for IWW papers and high-powered rifles.” I never had heard of IWW papers. My husband did have a high-powered rifle because it belonged to the National Association of Rifles, or something like that, and him and the miners would go into the mountains and hunt with his old rifle. He didn’t have it for no bad purpose. When I found out they was wanting that, I knowed these thugs were dirty—hired by John Henry Blair to come in there and break the strike. I said, “All these miners wants is a right to live in decent ways.” And the miners had their hands and their prayers—that’s all they had. But the coal operators hired these gun thugs. They buy them good whiskey to drink, they rent them good hotels, they give them high-priced cars to drive, and pistols, high-powered rifles, and one had a machine gun.

They could give that to beat the miners back. But to give the miners more to raise their children, they couldn’t do it. And then my husband and me finally left. But I’ll not go into the whole story, but, anyway, it was just like Hitler Germany. It was the worse thing I was ever in and I never will forget it. I’d stay there by myself, and I’d say to myself, “There’s something I’ve got to do.” They wouldn’t let the newspaper come in there, you know. And people would send in truckloads of clothes or food or something, but the thugs would meet them and if they wanted anything, they’d get it, turn it over so the miners couldn’t get it. They were trying to force them back to work.

Now, my daddy was killed in the coal mines in 1914, and he was loading a ton and a half of coal for 30 cents. After they got the unions they wouldn’t have done it. So, the union was the only thing stood by the men, but the coal operators didn’t want the union ’cause the miners would have a say—but anyway—I’ll try to sing this song.

WHICH SIDE ARE YOU ON?

Come all of you good workers,

Good news to you I’ll tell

Of how the good old union

Has come in here to dwell.

Which side are you on?

Which side are you on?

With pistols and with' rifles

They take away our bread

But if you miners hinted it,

They’ll sock you on the head.

They say they have to guard us

To educate their child.

Their children live in luxury

While ours is almost wild.

They say in Harlan County

There is no neutral there;

You’ll either be a union man

Or a thug for J. H. Blair.

Oh, gentlemen, can you stand it?

Oh, tell me how you can.

Will you be a gun thug

Or will you be a man?

My daddy was a miner

He’s now in the air and sun*

He'll be with you fellow workers

Til every battle’s won.

Tom: That’s right. Your song, see, that come out of experience. It was right there happening.

Florence: Yeah. The thugs, you know, I was trying to get some of them to answer which side they’s on—what’re you doing over there being a gun thug and shooting down your fellow men.

Tom: I can remember—that’s a bad situation.

Florence: They had the National Guard up in Harlan County awhile. They claimed it was going to be for the miners, but they got up there and they were for the coal company. They had two men that put up a soup kitchen. I’ve seen little children walking along the road down there, and their little legs would be so little and their stomachs would be so big. They didn’t get anything to eat. I’ve seen some of our good neighbors just staggering. Well, they put up this soup kitchen, think it was in Harlan or right below—two men, killed both of them same night. The thugs done it—pretended it was somebody else to get the miners. And they’d find bones up in the mountain where they had killed the miners.

Tom: This Barney Graham you’re talking about, after he was killed, I guess if one shot had been fired, no telling how many men would have been killed. But I’ve seen them walking around in there, and that Shorty Green fellow too, with big guns on them, you know. Several deputies, they called ’em “deputies,” them thugs for the company, they had their deputy badges and papers and everything. They’d walk around here, I’ve seen them, they’d lay a hand on them guns many a times over dad-gum crazy little old fights, lord have mercy. You’d stand around there innocent and just get shot down. But I didn’t think about it then. Actually I was around there part of the time hoping it would start, because they was men out there then, at that time, that I had it in my heart that I wouldn’t have cared to see them killed. Boy, I tell you what, when you get hungry and you go to bed hungry, and you cry and you know who’s crying because, of course, kids will, and there ain’t nothing to eat, and you don’t know where the next meal’s coming from, and you look at the next fellow out there and you know he ain’t in no better shape than you are. Then a dad-gum bunch of people running around there with a bunch of guns on, and if you look cross-eyed at one of them, they’d kick you or they’d knock you. If you don’t think it’ll make you mean—it shore will. I sure don’t want to go through that again.

*blacklisted

Tags

Fran Ansley

Brenda Bell

Florence Reece

Florence Reece wrote the famous song "Which Side Are You On" in 1931, at age 30, when she was a miner's wife and mother of eight. (1982)