This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 2, "Just Schools: A Special Report Commemorating the 25th Anniversary of the Brown Decision." Find more from that issue here.

"Five years from now, it may well be said that the entire situation was providential and segregation in the South was dealt its gravest blow ... when Governor Faubus used troops of the Arkansas National Guard to bar the admission of nine Negro students into Central High School."

Few observers of Little Rock's desegregation crisis in the fall of 1957 spoke with such prophetic accuracy as Gloster Current, then director of NAACP branches. Many people on both sides of the color line - in Little Rock and across the South - feared that public education would not survive the violence of the desegregation process.

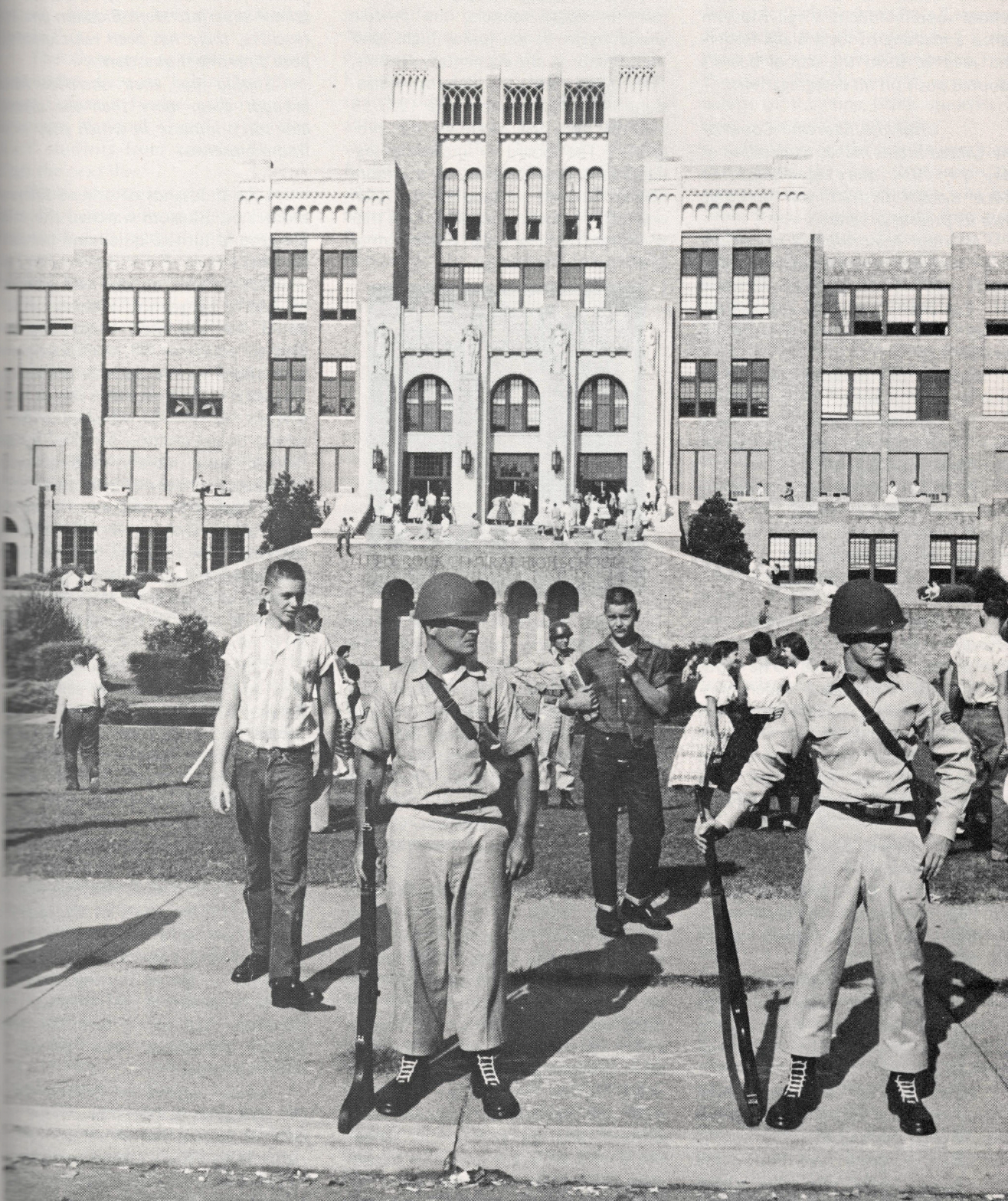

Yet today, not five but 25 years later, Current's prediction has been borne out more fully than perhaps even he could have believed possible. Through Orval Faubus and others like him, lines were drawn for battles which had to be fought were desegregation ever to take place in the South's schools. The Little Rock crisis symbolized the showdown between completely recalcitrant state power and a federal government committed to enforcing the Supreme Court's rulings. Those who chose defiance were eventually defeated, retreating to today's more subtle forms of discrimination. As a result, the student body of Little Rock's Central High School - where armed guards once had to accompany each black student to and from class , is now comprised of about 1,100 whites and 1,000 blacks; desegregation is accepted as an accomplished fact by the citizens of Little Rock, and the same holds true for hundreds of other schools and school systems across the South.

The changes began in Little Rock four days after the Supreme Court handed down its Brown decision. School superintendent Virgil Blossom called a meeting of local black leaders and read to them the school board's adopted position on desegregation:

... Until the Supreme Court of the United States makes its decision of May 7 7, 7954 more specific, Little Rock School District will continue with its present program.

It is our responsibility to comply with federal constitutional requirements, and we intend to do so when the Supreme Court of the United States outlines the methods to be followed.

During this interim period we shall do the following:

1. Develop school attendance areas consistent with the location of white and colored pupils . ...

2. Make the necessary revisions in all types of pupil records . ...

3. Make research studies needed for the implementation of a sound school system on an integrated basis.

In other words, the board intended to do a lot of paper work; no real action was planned. The optimistic mood of the black leaders present at the meeting quickly dissipated. L.C. Bates, publisher of the outspoken Arkansas State Press, rose and asked, "Then the Board does not intend to integrate the schools in 1954?"

"No," replied Blossom. "It must be done slowly. For instance, we must complete the additional school buildings that are now being started." Bates turned and walked out of the meeting.

A year after its original ruling, the Supreme Court elaborated on its decision by saying that desegregation should be implemented "with all deliberate speed."

It was left up to district school boards and local courts to figure out exactly what that meant.

Virgil Blossom and the Little Rock school board, like other school officials across the South, interpreted this phrase to mean "as slowly as possible."

According to the board's new plan, released in May, 1955, desegregation in Little Rock was to begin - 42 because of parental opposition to the alternatives - at the high school level; after being completed successfully in those schools, the process would begin in the junior highs, and then finally in the elementary schools. The board hinted, "Present indications are that the school year 1957-58 may be the first phase of this program." The board - including segregationist Dale Alford and the more liberal Blossom - adopted this plan only after attorneys assured them that it represented "a legal minimum of compliance with the law."

Many members of the black community grew impatient with the school board's slow pace. Early in 1956, the NAACP filed suit charging that the board was not complying with the Supreme Court's ruling. But both the U.S. District Court and the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the school board was acting in accordance with the Supreme Court's instructions to proceed "with all deliberate speed."

Vindicated by the courts, Blossom and his staff continued working towards token desegregation of previously all-white Central High School in the fall of 1957. Blossom tried to pacify people on both sides of the issue, assuring blacks that the board's commitment to desegregation was real, while protesting to whites that he was doing his best to make the process as slow and painless as possible. Both Blossom and the rest of the school board were subjected to intense harassment during the next few years for trying to carry out even a minimal plan of desegregation. In the summer of 1958, reflecting on the tumultuous '57-'58 school term at Central High, an editorial in the NAACP Crisis commented:

Since no one doubts that the past year has been sacrificial for the [school board members] as well as school superintendent Blossom and teachers, there has been reluctance to pose a pertinent question:

Should not their sacrifice have brought them more than the dismal and sorry impasse in which they now find themselves?

Like thousands of other Southern moderates, Blossom watched the middle ground turn to quicksand beneath his feet.

But in the spring and summer of 1957, as school officials anticipated the scheduled implementation of their plan that fall, the situation in Little Rock was deceptively promising. The voters had apparently voiced their support of the Blossom plan in a school board election in 1956 by defeating two rabidly segregationist candidates in favor of two moderates. Orval Faubus was elected to a second term as governor over the red-meat extremist Jim Johnson. And Blossom had succeeded in whittling down the number of black students interested in attending Central High from around 80 to nine.

The nine black teen-agers—six girls and three boys; one senior, two juniors, and six sophomores—were handpicked on the basis of their grades, health, and emotional maturity. During the months before school started, those students and their parents met often with Mrs. Daisy Bates, state president of the NAACP, and other leaders in the local black community to discuss how they might respond to the trials of the coming year. They were urged to be quiet, dignified, and nonviolent. “It is not cowardly to ignore slurring remarks,” advised a speaker at one meeting. “The Scriptures tell us to turn the other cheek. Remember that prayer is always in order.”

School opened on September 3, the day after Labor Day. “This is a time of testing for all of us,” editorialized Little Rock’s Arkansas Gazette. “Few of us are entirely happy over the necessary developments in the wake of the law. But certainly we must realize that the school board is simply carrying out its clear duty—and is doing it in the ultimate best interests of all the school children of Little Rock, white and colored alike. We are confident that the citizens of Little Rock will demonstrate on Tuesday for the world to see that we are a law-abiding people.”

The Gazette’s confidence proved ill-founded. Late on Labor Day afternoon, Governor Faubus called out the Arkansas National Guard to prevent black students from entering Central High the next day.

White moderates and black activists alike were outraged that Faubus had yielded to segregationist pressure and was using Little Rock as a pawn to further his own political ambition. “If it were not for my own respect for due process of law,” declared Mayor Woodrow Mann, “I would be tempted to issue an executive order interposing the city of Little Rock between Gov. Faubus and the Little Rock school board.”

The school board requested that “no Negro attempt to attend Central or any other white high school until this dilemma is legally resolved.” None did. On Tuesday, the federal district court, replying to the board’s request for legal instructions, ordered that the desegregation plan be carried out as scheduled.

On Wednesday, September 4, the nine black teenagers attempted for the first time to enter Central High, which was now surrounded by National Guard troops and an angry segregationist mob. Eight were accompanied by the city police and a group of concerned adults—including a few white ministers. They were turned away by the National Guard and went to superintendent Blossom’s office to demand an official explanation. But 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford had somehow not been notified of the group’s plans, and approached the school alone. Her encounter with the ugly crowd and with the National Guard blazed across the wire services that evening, focusing international attention on Little Rock.

Under pressure to see that the orders of federal courts were obeyed, President Dwight Eisenhower nervously called on Faubus to retreat or face federal intervention. Classes continued for the 2,000 or so white students at Central High, while the community awaited the results of a complicated wrangling between the courts, the school board, Faubus, and President Eisenhower.

On September 7, federal district Judge Davies denied the school board's petition for a temporary suspension of desegregation. Gov. Faubus traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, to meet with Eisenhower; he apparently convinced the President of his willingness to abide by the law, but still delayed withdrawing the National Guard. Finally, on Sept. 20, the federal district court issued an injunction ordering Faubus to remove the troops from Central High. Faubus obeyed but reiterated his conviction that there would be violence in the streets of Little Rock if black students tried to enter the school again.

His prediction proved self-fulfilling. On Monday, September 23, a loud and angry crowd surrounded the school. City police, directed by police chief Gene Smith, kept them from entering the school, but three Life magazine journalists and one black newspaperman covering the story were beaten by the crowd. The black students slipped in through a side door of the school, unnoticed and unharmed, but were removed later under heavy police guard as the crowd threatened to break through police lines and "drag the niggers out."

Ironically, inside the school things hadn't gone too badly for the black students. Some white students had walked out; others made rude remarks; one white girl slapped a black girl who, according to Blossom, "turned and said 'Thank you' and then walked on down the hall." But other white students had made friendly overtures, and some had even said that they hoped the nine would stay and work things out.

By Wednesday, the situation had taken another turn. The National Guard was back at Central High, armed with bayonets and augmented by 1,000 members of the 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Kentucky. But the troops had a new role: they were now under orders from President Eisenhower to ensure the safety of the nine black students as they attended Central High.

Violence in the streets continued throughout the year, and inside the school many white students who had been friendly were scared into neutrality by a group of extremists. One white student who refused to yield to the mob was 17-year-old Robin Wood. "I thought that the majority of the people were on my side," Robin told a reporter. "But I think that the fence-straddling kids have gone over to the segregationists."

The black students suffered from increasingly overt attacks. The harassment ranged from ugly verbal abuse - a group of white girls followed Minnijean Brown through the halls all one morning whispering "nigger-nigger" - to actual physical assaults. The black students were repeatedly kicked, slapped, knocked into lockers, and beaten over the head. Finally two guards from the 101st Airborne were assigned to follow each student from class to class. Minnijean Brown was eventually expelled for turning on her persecutors and calling them "white trash." "They throw rocks at you, they spill ink on you - and we just have to be little lambs and take it," was Minnijean's comment. During the year, school authorities expelled four white students and suspended about a hundred others.

The school year finally ended in May, with Ernest Green, now Assistant Secretary of Labor, becoming the first black student to graduate from Central. But there were to be no more classes in any high school in Little Rock until the fall of 1959. The school board asked the federal court to grant a "cooling-off" period – no more desegregation attempts until the fall of 1961; their request was granted but finally overruled after an appeal from the NAACP.

Meanwhile, Faubus was elected to a third term - the first governor in Arkansas in 50 years to be so honored - and passed a series of bills in the state legislature aimed at giving him extraordinary powers to curtail the desegregation process. On September 13, 1958, police served a proclamation on Virgil Blossom, stating that Faubus was using his new authority to close all the city's high schools. Incredibly, this outrage was accepted almost meekly by the majority of Little Rock's students and their parents; the only real protest arose when the school board cancelled the football schedule. With Faubus's willing consent, the city's football program was reinstated - the only school activity offered to the city's high school students that year.

Crushed by the defeat of their minimal desegregation plan and by what appeared to be the complete disintegration of public education in Little Rock, five of the six members of the school board - all except Dr. Dale Alford - resigned. At the next election, five ardent segregationists joined Alford on the board, and Virgil Blossom's contract as superintendent was terminated. Faubus and his segregationist cronies even attempted to legalize a plan for using tax funds to finance private education for students who objected to desegregated schools.

Eventually, the segregationists' excesses began to backfire, and the pendulum of public opinion began to swing the other way. In May of 1959, three school board members tried to fire 44 teachers and school employees for showing "integrationist" tendencies. Previously silent community leaders were finally galvanized into action. A Committee to Stop This Outrageous Purge (STOP) was organized. In a vote on May 25, the three school board members were recalled, and the new board declared its intention to reopen the schools that fall. The federal court invalidated Faubus's legislated school closing powers and placed the board under orders to desegregate under Blossom's original court-approved plan. By July, 1959, all but one of Little Rock's new segregationist academies had closed. (The exception was a school created and funded by Faubus himself.)

The schools opened on August 12, a month early, without National Guard protection and with very little violence compared to the previous year. About 1,000 segregationists did gather at the State Capitol for speeches and demonstrations, and later 200 or so marched off toward the school. But the city police halted the crowd a block from the school, arrested 21 people and effectively daunted those bands of segregationists who would have done violence to the schools.

From then on, desegregation in Little Rock proceeded in an irreversible, if snail's-paced, way. When the schools opened in the fall of 1960, there were eight black students at Central and five at previously all-white Hall High, but still no white students in any black schools. School officials were involved in almost constant court disputes over the next 15 years before full desegregation began in the early '70s, through a court-adopted busing plan.

The events of those first tumultuous years continued to reverberate. The State Press - published by black civil rights activists L.C. and Daisy Bates - was run out of business in the fall of 1959, and a similar but unsuccessful boycott was launched against the moderate Arkansas Gazette. In 1960 Orval Faubus was elected to an unprecedented fourth term as governor. The last two of the “Little Rock Nine” graduated in May of 1960. All nine went on to college, all to schools outside the South. In March of 1960, after months of harassment from segregationists because of his role in enforcing the peaceful reopening of Central High, police chief Gene Smith shot and killed his wife and then himself.

Dozens of others, both black and white, lost their jobs or moved away, unable to cope with the sneers and threats heaped on them for their connections with the desegregation success. Speaking of the “white casualties” of the Little Rock crisis, Mrs. Daisy Bates observed, “All of these white Southerners came face to face with the agonizing fact that the same system they had supported all these years—the same system that had been used to deny Negroes their rights—was now being used against them.

Tags

Chris Mayfield

Chris Mayfield is a freelance editor who lives in Durham and is copy editor of Southern Exposure. (1986)

Chris Mayfield is the special editor of this issue and a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1980)