This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 4, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons." Find more from that issue here.

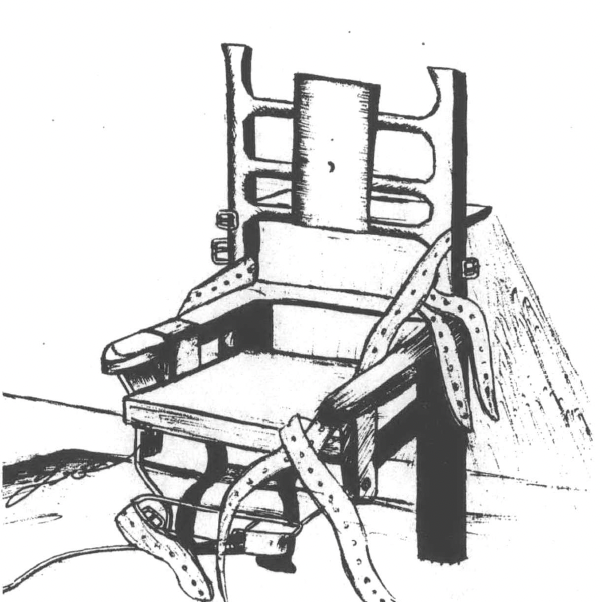

Societies define the value of human lives in countless and varied ways. In the most direct way, capital punishment laws announce not only that some lives are dispensable, but that the state has the right to decide who deserves to die. Our agents in this grisly task, juries in capital trials, select their victims not in the heat of passion or in self-defense, but with cool deliberation and malicious intent. This article examines some characteristics of the people we have chosen for death.

One of the most striking features of this country’s death row population is the overwhelming concentration of condemned prisoners in Southern states. Of the 395 prisoners now under sentence of death, 345 — more than 87% — await execution in Southern jails and prisons (chart 1). Here the modern version of capital punishment perpetuates a Southern tradition of violence that is underscored by statistics on the death penalty’s less sophisticated ancestor: lynching. Between 1882 and 1930, 4,761 persons were lynched in the United States, 77% of them in the South (chart 2).

The chilling resemblance between the two forms of killing by popular demand continues in the racial characteristics of the victims. Seventy percent of the victims of lynching between 1882 and 1930 in this country were black; in the South, four out of five victims were black (chart 3). When the Supreme Court abolished then-existing capital punishment laws in 1972, Justices Marshall and Douglas noted that the death penalty was disproportionately imposed on minorities and the poor. Despite the claims that the new, improved death laws safeguarded against racist application, blacks today make up 43% of the condemned prisoners in the United States as compared to 12% of the total population. In the South, blacks compose 20% of the total population and 45% of the death row population (chart 4).

We affirm the cheapness of black life not only in our greater willingness to execute black criminals, but in our harsher, bloodier punishment of crimes against white victims. In 12 Southern states, 87% of the victims of crimes for which the defendant was sentenced to death were white. Only 1% of the prisoners on death row in these Southern states are whites convicted of crimes against blacks (chart 5).

Courtroom experience bears out the conventional wisdom that defendants who can afford a privately retained, high-priced lawyer stand a much better chance of being acquitted, or at least receiving a lighter sentence. Yet in this most crucial battle of their lives, the overwhelming majority of condemned prisoners are represented by appointed lawyers who are often inexperienced or by public defenders who are typically burdened by heavy case loads.

Chart 6 shows the distribution between appointed, retained and public counsel for death row prisoners in the seven states where figures were available. These numbers refer to the lawyers currently representing condemned prisoners and do not take into account prisoners who may have retained private counsel only after losing their trials.

Lynch mobs were ostensibly illegal, but the actions of juries are legally recognized as the will of the community. By their deliberations and selection of the proper victims for official murder, modern juries — especially Southern juries — echo a familiar message: white skin and wealth are still the best tools for beating the death lottery.

Tags

Clare Jupiter

Clare Jupiter is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. She is now a lawyer in New Orleans. (1981)

Clare Jupiter is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. She now lives in New Orleans. (1979)