This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 4, "Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons." Find more from that issue here.

I Hustling

I was born in a small town called Siler City, North Carolina. I’m the youngest of 13 children. We were very, very poor. We were farming up until I was in the sixth grade.

We were basically a typical black sharecropping family, very poor and working a land for a white man, and we got nothing from the land except a shack to stay in and the little food that we grew in a small garden that we would tend after we finished tending his farm.

In the sixth grade we moved and we bought what was supposed to be a house, but it was really a shack. You could lay in the house and feel the breeze come in the winter time through the walls. My mother started doing domestic work, maid stuff, you know. Mopping floors for rich white folks, going in back doors and eating leftovers.

My father’s always been an alcoholic. I can remember him having a job a couple of times, but never long periods of time. It was a garbage collector’s job, or something like that. I never remem ber him not drinking. I attribute this to his lack of ability to deal with the ills of society and its frustrations, partially the degradation of the black man. I feel like he did this because he was frustrated and wanted to escape the unjust discrimination.

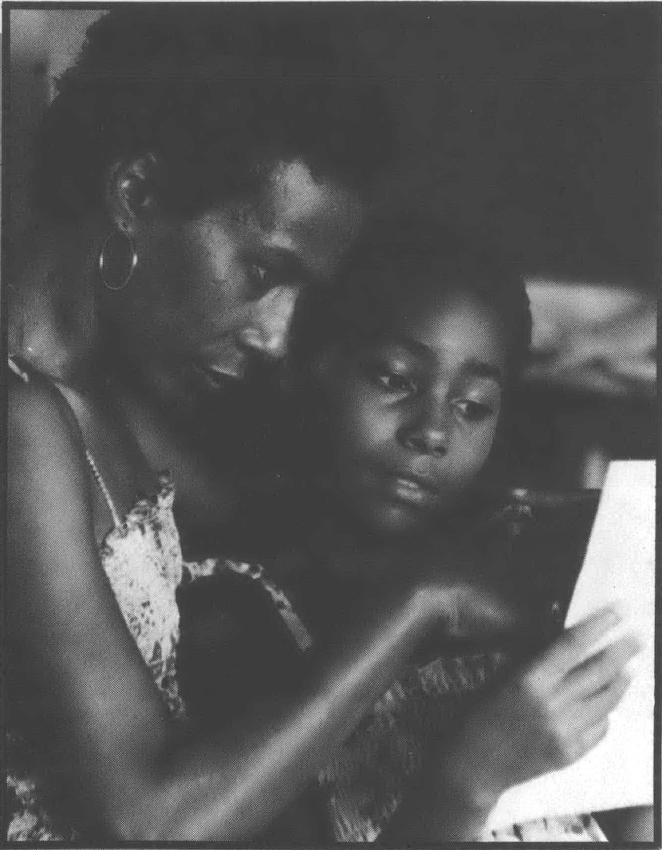

I was pregnant when I was 16 in the tenth grade. I quit school to have my baby. I have a daughter now, 10. Her name is Ayana, and I’m very proud of her.

I finished school when I was 19. Soon as I finished high school, I left home and started traveling. Even before I was out of school, I had started “making money,” what is called “hustling.” The first illegal money, illegal as far as the American government and tax courts is concerned, that I made was what they called “playing the till” — snatching money out the cash register while it’s open.

Most of my older brothers and sisters had moved away from home and were living in the larger cities up north and in Greensboro, North Carolina. I was going up there and I was meeting big city kids. Kids that are raised in the country are not exposed to as much of society’s ills as the kids in the city, or their oppres sion is less brutal in that their contact with society is limited to farming. Being around the kids in the city when I went to go visit my sister, I picked up on different things like getting high, “making money,” and talking slick. In the country, the most daring thing that we would do would be, maybe, steal your daddy’s whiskey. Or steal some sugar — that was very daring.

I started getting high and smoking reefer when I was in the ninth, tenth grade. When I made money, I always took it home to my mother, or part of it. I was bringing in some three or four hundred dollars, at least once a month. I was not on heavy drugs. I had the money and I didn’t know what to do with it. And I knew my family needed it.

One day Mom asked me, “Where are you getting this money from?” Of course, the first thing hit her mind, I imagine, was prostitution, me being a young girl and just beginning to go out and going to the city. And this is one of the first things poor parents fear, another mouth to feed. And she asked me where I got the money, and I told her, never mind where I was getting it, just spend it, cause I knew she needed it. And if I go to jail, just get me out. That’s all I wanted her to give back. My first encounter with the pigs was in twelfth grade. The postal inspector came to my house about some checks I had forged. Some stolen welfare checks out of Greensboro that a guy had stolen, gave em to me and I busted em for him. I got a portion of the money and he got a portion of the money. They came to my house looking for me one morning. That afternoon I had packed everything I had and I was gone, me and my daughter.

I hooked up with my husband, who was an old friend of mine dating back to grade school. We weren’t going together in school. But after he had went to the service and I got out of school, we hooked up and came back home. And we got married, and I started traveling. I lived in like four or five different states, and then I started messing with drugs, started using heroin, and I became a junkie.

My husband was in the Navy, and we were traveling a lot. But then we were traveling on our own, too, making money, doing a little bit of everything, mostly armed robberies. My husband and I worked together as a team, but mostly it’s individuals. The drug game is so cold and larceny-hearted, it’s not easy at all to hook up a group to make money, or a team even. Because everybody afraid the other one’s gonna rip them off. Because they know how they are, and they be thinking about ripping somebody off, and they be having a guard up against other people ripping them off. Occasionally I was still sending money home to Mama, because she’s still working to this day, which I regret. Basically, I think the reason I was into drugs was, it was what other people were doing, and it was something to do, other than just living, just existing and doing the everyday things that a normal life would be. I suppose you could say it was just being frustrated with how things are and knowing, or thinking, you can’t change anything, you just have to deal with it. And instead of actually dealing with it, you escape it through drugs.

I never tried to get a job. I had a couple of jobs, but it was just something to do, a change of pace, you know, because I never actually wanted to work. Then when I got married, my husband didn’t want me to work. And then I got frustrated sitting at home, so I finally decided that I should work, to get out of the prison of home, of the housewife bag, and I got a little job.

My daughter was with me. We spent a lot of time together then, but after she was three, that’s when I got on drugs, and we didn’t spend so much time together anymore because a junkie’s first love is drugs. Regardless of what anybody says, he loves drugs better than anybody else.

It was a gradual kind of thing. When you first start doing it, you’re doing it because, you know, it’s there, and each day you doing a little more, til you reach the point — I actually didn’t think I had a habit for four months, and I was shooting dope every day. And I’d swear I didn’t have no habit. Then when I missed one day, because there was no drugs in town, then I knew I was a junkie. I admitted I was a junkie, because I was very sick.

It wasn’t hard to get drugs at all. That’s the problem. After you get on drugs, then it’s hard. But when you first start, you have your first sample free. That’s how they get their clients. I was about 19 or 20. Before then it was reefer and pills, red devils, stumblers, yellow jackets, then acid. I took acid for a while.

II The protest

The first time I got busted was in North Carolina, for forgery — a personal check that was taken out of an armed robbery. My husband got busted at the same time for armed robbery. They wanted to bust me for the same armed robbery because he had a woman accomplice. But they couldn’t bust me because I had a perfect alibi and all kinds of witnesses. I was going to business school in Siler City and at the time the robbery jumped off, I was sitting in my typing class. So they couldn’t actually hook me up with the robbery. So they charged me with accessory after the fact of armed robbery, which is nothing but saying you knew about it but didn’t tell us.

I stayed in jail for like ten days. Right after I got out of jail, I got a lawyer with some of the money I had been making during the armed robberies. My bond was S 10,000, and I couldn’t afford it. I faked a nervous breakdown in jail. And the doctor come in there and gave me a shot of some shit, I don’t know what it was. But it had me knocked out all night and the next day. Because they thought I was ill — I was kicking a dope habit — they decided to give me a bond that I could make. So they reduced the bond to $250, from a $500 bond.

When I got out, I got my husband an attorney that I paid $2,500. It was nothing but a ripoff. He still got 20 years, in August of ’72.

In the meantime, while we were out on bond for that — before we went to court for that robbery — we had moved to Virginia, and we were still using drugs. A junkie that we knew planted some drugs under our living room couch and called the man. Well, we had drugs anyway, you know. He didn’t have to plant it, we had plenty drugs anyway. As I understand it, he had cases uptown himself that they threw out of court cause he set us up. And we got busted up there and we were both put in jail.

My husband got nol prossed, which means that they can reopen the case at any time. He got me out on bond the next day after he got out. We came back to North Carolina to stay. During that time we came back was when he got the 20 years. And while I was out on bond, they revoked my bond, and the bondsman came from Virginia, came down here and picked me up one Monday night. They told me that I was going up for a hearing, right? They didn’t tell me they were revoking my bond. When I got up there they threw me in jail. I went to court up there and got two years state time.

For 15 months I was up there. I got out in ’74. I can look back now and I see some messed-up things, but at the time, everything was cool with me. Because you had your own private room. It was all pacified, you know, it was all candy-coated. You couldn’t actually see the prison bars, but you knew you better not go out that gate. It was set up like a college campus. Not even a fence around the place.

That’s one thing I want to speak on, the psychological control of women in the prison. It’s said that men are treated worse than women. I agree. Physically they are, I assume. But what people fail to understand is physical can heal much easier than mental. It takes time and a lot of hard work to heal your mind, when your mind is warped. And that’s exactly what happens in women’s prison. Women are controlled psychologically, not physically. They have the physical restraints. They have the mace and the sticks and everything, but they’re not used as quick as with the men.

But they have psychological control over the women like a mother-daughter, parent-child relationship. She’s made to feel like a guilty child, a child that’s broken a rule and deserves punishment. And she accepts her punishment as a passive child, because she feels inferior, first to society, and second to the prison authorities. So she’s made to look and feel and act like a child. And she submits very, very easily.

What tripped me out, when I was on the receptive ward, and when this broad walked into the room, everybody’s supposed to stand up. Whatever you’re doing, you supposed to drop it and stand up like this is your maker and taker coming in, right? I just couldn’t deal with that. I didn’t get up at all, and I wasn’t the only one.

Well, they didn’t want us to know that they didn’t appreciate us not getting up. It was never mentioned until they went out. Then, some older in- mates come over to us and ask us, “Are you crazy? You didn’t stand up. That was the superintendent that just came in.” And I said, “So what? I wasn’t in her way, what I got to get up for?” She said, “They have to get up. Show her proper respect, you know.” It kind of tripped me out.

Their control mechanism there is lockup. When you’re bad, you know how your mother sends you to the room when you do something wrong. Well, that’s the way they do in prison — you go to your room, you spend 10 days in your room for being a bad girl, for doing this and that, for talking loud in the line. When you walk, you got to walk in two’s, you can’t say a word while you’re walking, and all this freak garbage. It’s petty stuff, you know, but you’d be surprised to see how effective this petty stuff is. People say, well. “I’ll just go on and do this because it’s petty, it ain’t going do nothing. I’ll obey these jive rules.” But all the time when you’re obeying the rules, you’re not actually understanding the rules. You’re not actually understanding how you’re being controlled and how you’re being turned into a zombie. So, it’s very vicious.

But, back to my (laugh) adventurous life. I got out of prison in ’74, out of Virginia, learned nothing. I got out just as ignorant as when I went in. I went to a little typing course, when I was there, but you know, I never used it, all I got was a file clerk certificate. Then I got busted and went to prison in Raleigh, North Carolina, in ’74, for forgery. And I got five years. It was at this time that it really dawned on me, after going to Raleigh, because Raleigh is raw, naked repression. They don’t try to disillusion you at all about being anywhere other than in prison. They want you to know you’re in prison. They don’t try to make it look like no college campus, they don’t try to make it easy, they let you know you’re doing hard time.

The living conditions are ridiculous. You can lay in your bed and reach over and touch the next woman laying in her bed. That’s the footage space between the beds. And there’s always a bunk on top. There’s no single beds. It’s a dormitory with 80 beds. And you got four commodes in there with 80 women. And four, maybe six, face-bowls. The heating system is worse. No air, no ventilation.

III Busted

I was in there five months before the protest jumped off in 1975. It was a couple of incidents that brought it about. One was with a sister that was complaining about side ache, and the nurses kept telling her she’s faking it, trying to get off from work. She wasn’t faking it; she had appendicitis. Her appendix erupted on her one night, and now she wears a bag the rest of her life.

The other incident was with a younger sister, a beautiful sister, that transformed along with myself into a warrior, a conscious warrior, and started doing conscious work, conscious struggling. She refused to let the guards search her. The guards wanted to strip-search her for an alleged razor blade she was concealing, you know, to jump on another inmate. And two guards wanted to strip-search her. And she refused to let the men strip-search her. Which I would have too. And in the process she tried to go out the door to holler to us and tell us what was happening. She opened the door and was leaning halfway out the door, and the guards just slammed the door and her head went through this big plate glass in the door. And it busted the door and cut her head up, right? And they rushed her to the hospital and stitched her up and they brought her back and intended to put her in isolation, on a concrete floor, with a concussion. And, we couldn’t hear it, you know, we couldn’t deal with that, right?

And we had our first protest, which was like 40 people. We refused to go back to work until they brought her out of the isolation and put her in the hospital ward. We were very effective that time. And this was like two months later that we decided to have the major one. It was just a decision that we had made about the conditions that we were living in and the incidents and events that had been happening. Our demands were that there be an independent investigation of the hospital. One Sunday afternoon, the fifteenth of June, we decided that we weren’t going in at eight o’clock. Usual lockup time is eight o’clock. We had put the word out on camp that everybody should get their blankets and pack a lunch. We were ready to sit out all night, because we were protesting the conditions and treatment of women in prison. Over 50 percent of the prison population turned out. It was done very well. It was mobilized, but we didn’t have organizing. That caused some of the, I guess the small defeats, physical defeats that we had. We should have organized people more around what was going on and what could happen. We underestimated the state and the agents of the state, and we overestimated their human concern.

We went to sit on the lawn and nobody asked us to go in. The sergeant come over and asked us what the deal was, and we asked him what it looked like. And he didn’t say anything else. He left and went back and called up his officials and told them what was happening.

About 12 o’clock that night, Mr. Kea, the superintendent, came out with Walter Kautsky, the assistant director of prisons. They asked us to go in, and we told them we could not go in because we wanted to see the governor. We wanted to expose conditions, unless they decided they wanted to deal with them and change them. They gave us a lot of promises about the governor was out of town, and they could do something when he came back, and not to worry about it. Just go on back and live a normal convict life now, and when the governor comes back we’ll help you out. And of course, we refused, saying no, nothing happening, we’re not going no place. Four o’clock in the morning they came back again and asked us to go in the gym, where they had mattresses laid out on the floor, and surrounded by guards that they had called in from the other prison camps. We refused to go in the auditorium. And at 5:30 in the morning, we had laid down to go to sleep, and formed a circle.

The guards came in riot gear: helmets, mace, tear gas, sticks. They formed a circle around us and started picking us up. Snatching and hitting sisters with sticks and things. It was a decision that we had made among ourselves that we were going to be nonviolent, very peaceful, let em be carried. Don’t walk, be carried. All we wanted to do was talk with the governor, present our demands and see that they were met. But the guards didn’t see it that way, and they came in full force, ready for a fight, swinging clubs when they came in the door. So we fought back, very accurately too, I think. Guards were jumping over the fence and things. It was about 350 guards that day, and about 350 women, too. Well, the first night it was less guards, I would say 200. That Thursday when they came in, it could have been one-on-one guards.

Seven o’clock in the morning after we had fought, and women and guards had gotten hurt, Kautsky asked the troops to retreat, ordered the troops to retreat. We went in for negotiations with the director of prisons, assistant director and some heads, high officials. And nothing was resolved. Another date was set up for that Thursday morning. We had control of the prison from Sunday until that Thursday. And it ran very effectively. Women were very responsible. It was no escapes, no fights or anything. It was about four matrons on the whole compound, the ones that weren’t afraid that the inmates would do something to them, I guess.

That Thursday we were supposed to negotiate again, but that Wednesday they sent out an unsigned paper saying what demands they were going to meet, which was practically all of them. But the catch was, there was no signature on the paper. It was typed up, and there was no state seal on the paper. So had we went along with it, that would have been it. Cause they weren’t obligated to fulfill any of it. It was a trick, and some of us happened to catch it. We sent it back and told them, no way. Negotiations set for tomorrow morning, and we ain’t negotiating before then, either.

The original plan was, that they were to come on the yard, and we were going to set up tables and speak to the body, not a negotiating team, like we did Monday. Because I feel like, I can’t speak for all those sisters. I’m not going to be feeling the licks that these sisters are going to feel. So Thursday morning they sent for the same negotiating team they had Monday. I was on the first negotiating team, and I wasn’t about to run up in that snag. Cause I know it was nothing but a trap. The plan was, I found out later, that they were going to take that same negotiating team out the back door to the men’s prison. Another negotiating team was made up, and stayed in there from eight o’clock that morning til seven that night and come out crying. They had gotten nowhere. We had asked them, begged them not to go in, make them come on the yard and talk to us. But they went in, and five minutes after they came out the director of prisons, Ralph Edwards, came out and say, “We’re giving you 10 minutes to get back to the building. If you ain’t back, we’re dragging you back.”

Mr. Kea’d been fired. Got a new superintendent, Mr. Powell, another black man. Another token. And we were very upset, very disappointed, and people started voicing their opinion and arguing. And we decided to go on back to the dorm. But on our way back to the dorm we were stopped by the guards for a fight, because they were holding a lot of hostilities from Monday. We were pinned against the dorms with the guards in front of us, and they forced us right into the door that they knew was locked. They were doing us a job, and a lot of sisters got hurt pretty bad. Clubs and tear gas; glass was broken.

After we had fought for like two hours, and we had kind of patched up the ones that had gotten hurt and sent the ones that were hurt bad out on stretchers, they backed buses up to the door and called out specific names, who should get on what bus. One of these buses, 34 women were on. We were shipped to a men’s unit, 200 miles away from Raleigh, up in Morganton, North Carolina, up in the mountain area. On the sixteenth floor we were put in individual cells. Seven of us stayed there for three months. In between times they were selecting ones that were being good girls, bringing them back. They made three trips: one the first month, one the second month and one the third month. The last ones, the ringleaders they called it, came back the third month. We got back to Raleigh, we continued to stay on lockup. Five of us stayed on lockup for a year.

You stay locked up 24 hours a day. You get out two hours a week for recreation, exercise. After the first year, the five of us got off lockup, and I stayed off for six weeks. Then, it was an assault on a captain. Some six women assaulted the captain after he had jacked this sister up and threw her against this fence. One Sunday her mother came to see her, and because her mother didn’t have a proper picture ID, they wouldn’t let her mother in. But the same mother had been coming to see her all along. They knew her by face. And this particular Sunday they wouldn’t let the mother in. The sister, of course, got angry, and she went to the captain, went to the administration building, which was forbidden on a Sunday. You know, they don’t want no inmates around when the visitors are there, cause we might act like convicts, you know. When she went over there the captain got mad and said she had no right to come over there because it was visiting Sunday and she ain’t supposed to be there with the visitors.

She say, that’s her mother and she want to know why she can’t come in. During the process the man told her she was going to lockup. She told him she ain’t done nothing to go to lockup for. And he jacked her up and threw her against the fence.

And when them sisters on the yard saw him, they just went to her rescue, to defend her, cause this man weighs three hundred pounds, about six-seven, and the sister weights a hundred and ten, about five feet. So the scales had to be balanced, and the sisters balanced the scales. And because of that, at random, six of us were chosen to go on lockup, and I was one of them. Our disciplinary statements read, “according to ten statements signed by ten inmates, these six women assaulted Captain McLam on a certain day. But they stated clearly, they had no evidence. No staff member saw the assault.”

We never saw those statements. Our lawyers couldn’t even see the statements. We were put on lockup. We were given different sentences, ranging from no time on lockup — one sister got cut loose completely — to six months on lockup. I got six months.

IV Dealing on the system

All the time I had been studying and understanding what was going on. Why it was a need for a protest, what happened after the protest, why it happened like that. Why the state became so vicious, and reacted so viciously, from a peaceful protest by women, unarmed women. I began to ask the questions of myself and I had literature I began reading and studying so I could answer them myself. And for the other women, the officers even, when they would ask, why they were so frustrated with their jobs. Why it’s a need for prisons. Why some people do all the work and make no money and some people do no work and make all the money.

When I went back on lockup the second time, I decided I wanted to take a correspondence course in political science out of Franconia College in New Hampshire. All my books were black history, Marxism and revolutionary theory. And of course, the pigs saw the books coming through the post office, and they couldn’t stop it because it was a federally funded program.

So they did the next best thing: they jacked me up. And I never got off lockup. They never ask you questions relevant to you getting off lockup. The questions are always like, “What are you studying? Who are you writing? Who do you know? How many organizations do you know?” I noticed the folder they had in there. They had xerox copies of my own handwriting, my letters that were supposed to be going out and letters that were coming to me. I knew that they couldn’t have gotten any letters out of my cell, my cage, to xerox, so they had to xerox it coming in and out.

So when they started asking me what I was studying, I was telling them, “Black history.” And I had a medallion on my neck, a wooden clenched fist. The man asked me, “What is that?” I told him, “It’s a medallion,” right? He say, “What does it mean?” And, you know, this man was asking me to deny my princi ples, deny my symbols, right? And my colors — I had red, black and green on, a hat, I think it was. And they want to know what that means, right? So I explained it to them. They asked me was I anti-government, anti-US government. I told them I was anti-anything that oppressed my people. Then they want to know who my people are. So I tell them my people are any oppressed people, and both are human beings, right? So, they told me that I should take six more months on lockup.

So that’s another year that I spent on lockup, for my studies and my direction. Of course, I called my attorney and told him that they were locking me up for my beliefs, but by the time he got there, the charge was plotting to escape. I went back to the board again for plotting to escape and I said, “Plotting to escape? Where’s the evidence?” These pigs tell me they got an anonymous phone call from outside the prison, saying I was getting ready to plot — sitting in a maximum security lockup. The cell was a four-bed cell, but it was strict orders that I should be by myself. That let up after about six months. They decided they weren’t going to break me, so they put somebody in there. After that, they started threatening me physically. The head of custody come in one day and called me out and talked to me in the lobby. Nobody was sitting at this little table but me and him, right? And he say, “You know what, you not going to ever get out of the prison alive.” I said, “What did you say?” And he looked at me and laughed. He say, “I said you not going to ever get out of dorm C.” I said, “No, that’s not what you said. You said I wasn’t going to get out of prison alive. Are you threatening my life?” He said, “Do you think I should threaten you?” I said, “I don’t know. If you feel like I’m threatening you, then it would be logical to threaten me.” And I told my attorney that. By the time the attorney got there, of course, the superintendent had never heard the conversation before. So out of the three years I was in prison, I spent two years on 24 hours-a-day lockup as a result of my beliefs and my activities and the protest in ’75.

My husband died in April of ’77. He had been on escape for two years and he was hitchhiking and got hit by a truck, on 85, outside of Durham. I got off lockup in June of ’77, for the second time. After my husband died, I feel like that had some influence on me getting some play about getting off lockup. They were only going to let me go home for two hours, just for the funeral. My sister got in touch with a state senator, McNeill Smith out of Greensboro, Guilford County. And he called down there and demanded that I be given a 12-hour unsupervised leave. They sent two pigs with me to the funeral.

After I had went to the funeral and come back, they all gave favorable reports of my behavior at the funeral. This allegedly helped me get off lockup and all this good stuff. But after that, my goal was to still deal on the system, but get out of prison as soon as possible, cause I saw how I was being crowded and hampered in there. The only thing I could do was get out of there because it was obvious that I was never going to get on the campus again to do any kind of work, to deal with anybody. I felt like I had grown as much as possible inside a cell, and the next strategy I worked on was getting out of prison. And I got out.

Tags

Nzinga Njeri

Nzinga Njeri now works at Africa News, a Durham, North Carolina, news agency, where she is being trained as an audio technician and on-the-air broadcaster. (1978)

Clare Jupiter

Clare Jupiter is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. She is now a lawyer in New Orleans. (1981)

Clare Jupiter is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. She now lives in New Orleans. (1979)