This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 2, "Just Schools: A Special Report Commemorating the 25th Anniversary of the Brown Decision." Find more from that issue here.

Rebecca Henry was an eighth grader in 1965, anxious to share the more sophisticated facilities, plentiful supplies and better education rumored available behind the doors of all-white schools. Now a Clarksdale, Mississippi social worker, Ms. Henry was a plaintiff in a school suit that eventually opened doors of all-white Cohoma County schools to blacks. But it wasn’t until she finished high school that black and white students shared those facilities, supplies and opportunities.

“I was really looking forward to it,” said Ms. Henry, 27. “Now, I don’t know if I would like it because the black kids going to school don’t have anything. They really don’t seem interested in what’s going on in school anymore. Just because the courts say the black and white kids will go to school together doesn’t mean their mamas and daddys are going to accept it or help make it work.”

Although desegregation finally brought black and white youngsters together in schools, it has not been the cure for racial inequality in America, as many blacks had hoped. Problems which cannot be solved by crosstown busing or bending attendance lines still cripple the effort to provide an integrated education.

“To just dismantle the dual school system is not sufficient to integrate schools,” said Dudley Flood, a North Carolina Department of Instruction assistant superintendent. “It allows people access but it doesn’t assure it. Those vestiges that deprive people of equal education still exist today… We still have people in schools this morning who believe they’re not worthy of sitting next to a white person and white people who believe the same of them,” said Flood, who has served as a desegregation consultant to more than 500 school systems outside North Carolina.

Equal status relationships must be taught to both races before integrated education can begin, says Flood. As it is, the status of black and white students in desegregated schools most often reflects the many years of racial inequality in America. For example, the bulk of the black students are in courses for slow students. Remedial programs, often poorly organized and financed, are dominated by blacks. And for the most part, an obvious racial division separates students in classes, cafeterias, on school buses and at school activities.

Black students are suspended at a disproportionate rate to their white peers in desegregated schools. Black students make up a disproportionately high percentage of dropouts and severe truants. Few black students are found in programs for gifted and talented students compared to the many found in classes for low achievers, mentally and emotionally disturbed or retarded students.

There are some obvious reasons why desegregation has not improved the quality of education for blacks greatly. Key among them is the decline in black teachers and administrators. In January, 1979, the North Carolina Human Relations Council gave the state board of education statistics showing a severe decline in the number of black teachers and administrators over the last decade of school desegregation. Of the 145 systems, 89 have no black administrators, 38 have no black principals, 12 have no black elementary teachers, 14 have no black junior or senior high teachers, and 59 have no black guidance counselors. No district has a black superintendent, even though nearly 30 percent of the state’s 1.2 million public school children are black. In 10 years, the number of black high school principals dropped from 42 to eight (according to responses by 61 of the state’s 145 school districts). Black assistant principals, meanwhile, increased from 11 to 79. Black teachers in junior and senior high schools fell from 1,128 to 843, and black elementary school principals dropped from 112 to 79. Despite this report, the state board voted to raise the required scores on the National Teachers Examination, a test which many feel is biased and inappropriate to evaluate black educators’ skills.

In desegregated systems dominated by white educators who have not adapted to different lifestyles of blacks, black students are being excluded from the educational process by factors including irrelevant curricula, hostile teacher attitudes, labeling and administrative and teacher irresponsibility. Educationally, such practices result in test scores that show black students, from Arkansas to Virginia, achieve on an average of two to three years lower than their white counterparts by junior high school. And the North Carolina minimal competency test, based on math and reading skills a sixth or seventh grader should have mastered, shows black students who have spent most of their lives in desegregated schools are failing at far higher rates than whites.

For Baker Smith, a black Charlotte, North Carolina, high school senior, desegregation is a pressing personal issue. Baker, 17, is an honor student at South Mecklenburg High, which has more than 2,000 students, 561 or 28 percent black. The school is located in affluent southeastern Mecklenburg County. His mother, Carleen, attended the old, all-black Highland High School in Gastonia, about 20 miles southwest of Charlottes. His father, Nathaniel, attended West Charlotte, the county’s only previously all-black high school still intact.

According to Baker, blacks are a minority in the school and too often accept a separate existence, different treatment or an attitude of “just getting by.” “All the things that are available to whites are available to blacks,” Baker said. “The main problem is once someone tells us we can’t do something, we accept that. Once we fail to do something that one time, we accept it too easily.” For example, Baker said only one year of math is required for high school students but those planning on attending college need more. Rather than taking the additional math, Baker said, many black students rejoice at completing the required year. “Desegregation has got blacks doing just enough to get by with a D,” Baker said. He tried to organize a youth group last summer to help motivate students doing poorly in school after he was spurred by Rev. Jesse Jackson’s speech to high-school students in Charlotte. “And the ones doing enough to get by see big dollars in the future. They are going to look for one of those highly skilled jobs, making seven dollars an hour. They don’t know these jobs won’t be there for them.”

Apparently, much of the problem in desegregated schools evolves from how white teachers and administrators relate to black students. It’s a struggle, easier to ignore than face, for the uncommitted or unprepared white. Too often white teachers and administrators can only see success coming from a generally fruitless effort ot force black students to meet a white, middle-class mold.

Baker, in desegregated schools all his life, says he’s seen it throughout. “Whites naturally achieve more because we have more white teachers,” he says bluntly. “They had the same bringing up and the same culture as white students. Therefore, the white teachers can teach white students better….But black parents don’t seem to give a damn. I would say that 95 percent of the black parents don’t know their children are cutting class or smoking dope, or they’d die. But these parents will curse teachers out when they call over some trouble.”

Baker says desegregation and equality are supposed to be one and the same. And his plans for the future are based on personal ambitions to see that equality be ensured for all. “Believe it or not, I hope to be a judge one day. To me, a judge does have the power of justice. I’ve seen or read about so many cases when they’ve abused their power and others who don’t use it to its full extent. When I was younger I said I wanted to be president; then I said I wanted to be a senator. But I realized senators don’t really have power because they always have to make those compromises. When you are a judge, you have a decision to make and you have the power. It might be appealed later, but you can make the decision. I’d like to cut down on some of this injustice and prove that our court system can be what it is supposed to be.”

Baker’s plans for the future are no more ambitious than his present undertakings. He studies an average of 12 to 15 hours weekly, drives a school bus and works part-time at a department store. The money helps his mother, who is sick and divorced, balance the family’s budget.

Baker says he views every day under the present system as a step backward for black students. “We need to get rid of the competency test at the high-school level. It’s an incentive to drop out. But the main problem is black apathy, and I don’t know what to do about that.”

Ora Stevens, of Marianna, Arkansas, views desegregation from the perspective of a black educator and mother of two school-age children. She carefully monitors her children’s schools and picks the “real teachers” from those controlled by their prejudices or inadequacies. Even her advocacy role doesn’t provide the answer to all the problems a black student faces in desegregated schools.

“A big part of the problem is that our children don’t know who they are in desegregated schools,” Mrs. Stevens says. “Black youngsters have a poor self-concept. I can’t instill it in my own child if I have a poor self-concept. Our children are running around, in some cases, wanting to be white because their self-concept is more positive. This school system is 76 percent black and about half the teachers are white. And they are not tuned into the minds of black people. Before coming here, they’ve never worked with black students.

“It’s very seldom I talk to a student who says I want to do this because my seventh grade teacher did. We don’t have good, positive models anymore and I don’t know why. It’s detrimental too for black teachers to be anti-white. It teaches the child to grow up with certain kinds of negative attitudes about other people when that isn’t what we’re all about. We need to teach them to respect all people, but to be a model for our kids so that we don’t have to be afraid of what we don’t know about.”

She said school curricula aren’t geared to black children and a battle must be waged for change. “The curriculum is not relevant,” said Mrs. Stevens, a desegregation specialist in the Marianna school district. “Kids have to have something to identify with. We’re saying those things all the time but nobody’s listening. We’ve got to keep fighting for change.”

Too many blacks, she thinks, have accepted token integration or become preoccupied with their personal ambitions and comforts. “I can’t see any progress; numbers don’t necessarily represent progress. The system has put black people in a position where we can’t feel proud because we’re not doing anything. Our kids don’t respect us because we sit back and take it and say we have families to feed. What can we do? After all, we’re a very small minority. Before, even though we weren’t in a position to have everything, we had pride and hope….You see, we’ve lost that.”

The role of pride and the parents’ influence on their children’s desires for quality education comes through strongly in the story of the Monix family.

Clarence Monix grew up in Duncans, Mississippi. There was nothing particularly distinguishing about his early life. He attended an all-black school with barely enough ragged books to go around. After eight years, he quit. His wife Lenora grew up in Grace, Mississippi. As a youngster, like her husband, her growth and development suffered from the law of the land mandating blacks a lesser, humiliating role in society. After 12 years she left school.

Today, there are 10 children in the Monix family. Monix, a respected member of the Clarksdale, Mississippi community, owns a fencing and plumbing company. They have two children in college; one who works with Monix in the family business; six home, students in grades three through 12; the youngest is three years old.

Beginning with Clarence and Lenora Monix, the family represents a generation of school segregation and at least two generations of school desegregation. How much the changes have affected their rise in economic, educational and social status cannot be easily determined. But their viewpoints on the subject are enlightening.

Monix, 48, sees advantages for his children in school desegregation. “Whereas when I was coming along, we were always fed with black people and were taught with black people, my little kids are reared around white people and taught by white people. They have nothing to back up from. My kids move so fast and learn so fast I can’t see where they got it from. They get straight A’s.

“I guess they could do as well in all-black schools because we’ve got some real good black teachers,” he said. “Back in my day, the white people held the best back.”

“The advantage to school desegregation,” Mrs. Monix said, “is there is more to offer in desegregated schools than there were in all-black schools. I didn’t learn what these children have learned in the ninth, tenth, and eleventh grade. We didn’t have the books. There were no libraries when I was going to school. I went to a one-room church in the country. We had two teachers for the first through eighth grades. We had to walk to school and in the winter we’d freeze to death. There was one heater in the middle of the church. Now they have buses running right at the door, taking the children to school.”

Mrs. Monix said school desegregation has been good for her children except for her oldest son, Donnell. “He didn’t finish. That was the year they began desegregating schools. They marched and he went to jail. After that year, he didn’t go to school anymore. But the others didn’t have to go through all that stuff.”

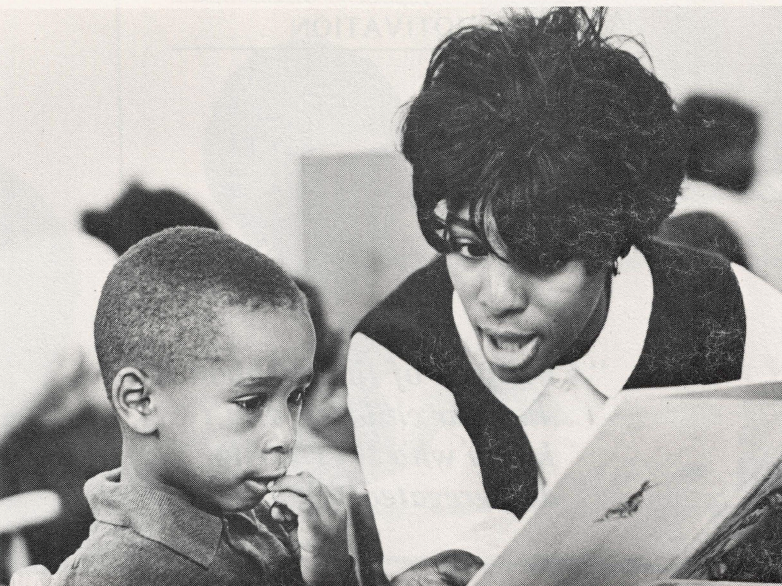

Clarence and Lenora Monix say they haven’t spent a lot of time helping their children because they had an inferior education, but they have, by overcoming their own poor beginnings, served as demanding and motivating models. “We’re kind of old-fashioned,” Mrs. Monix said. “I believe in my children coming home from school and doing their school work and not being out in the street. All of our children play in the band and Saturdays they practice and get their lessons. Sunday, after church, they practice and get their lessons. The older children help the younger ones. They tell them what they need to do to prepare themselves for college.”

The Monix children, in addition to Donnell, are Clifton, 23, a graduate student studying electronics at Memphis State University while working part-time as a local disc jockey. Shirley, a 21-year-old speech major at Jackson State University, is editor of the school newspaper. Dalphine, 17, is a senior at Clarksdale High School. Anthony, 16, is a junior at the high school. Tamara, 14, is a ninth grader at Clarksdale Junior High School. Lisa, 12, is a seventh grader at Riverton Elementary School. Clarence, Jr., 10, is a fifth grader at Oakhurst Junior High School. Diana, eight, is a third grader at Booker T. Washington Elementary, and Jimi, three, is the youngest.

“I don’t think anybody should go to school with only one race,” Dalphine said. “It seems like they’re missing something. A lot of people say I don’t want to be around white people, I’m tired of white people, but you’ve got to face it sooner or later.”

Dalphine talked about a long struggle by black students to get a black homecoming queen. Although the school is majority black, she said the white principal met with whites alone and told them who to vote for. She said cheerleaders, under school rules, are supposed to be racially balanced, but when a white cheerleader drops off, a black alternate isn’t allowed to replace her. But a white alternate can replace a black cheerleader who quits.

“A lot of parents tell black kids they are going to push them until they make it. But daddy’s saying to us ‘I didn’t make it but you’re going to get there.’ I think more support from their parents would help other black students a lot. My sister is going to Jackson State, which is predominantly black; my brother is going to predominantly white Memphis State, and I’m going to the University of Mississippi at Hattiesburg, which is predominantly white. I think I am going to have a hard time—matter of fact, I know I’m going to have a hard time. But I want to show them I’m a person. I might not be able to do it as well as they do it, but I’ll do it, and I’ll be there trying my best.”

Tags

Charles Hardy

Charles Hardy wrote for the Washington Afro-American and Washington Star before beginning his present job with the Charlotte Observer in 1975. (1979)