This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

Editor’s note:

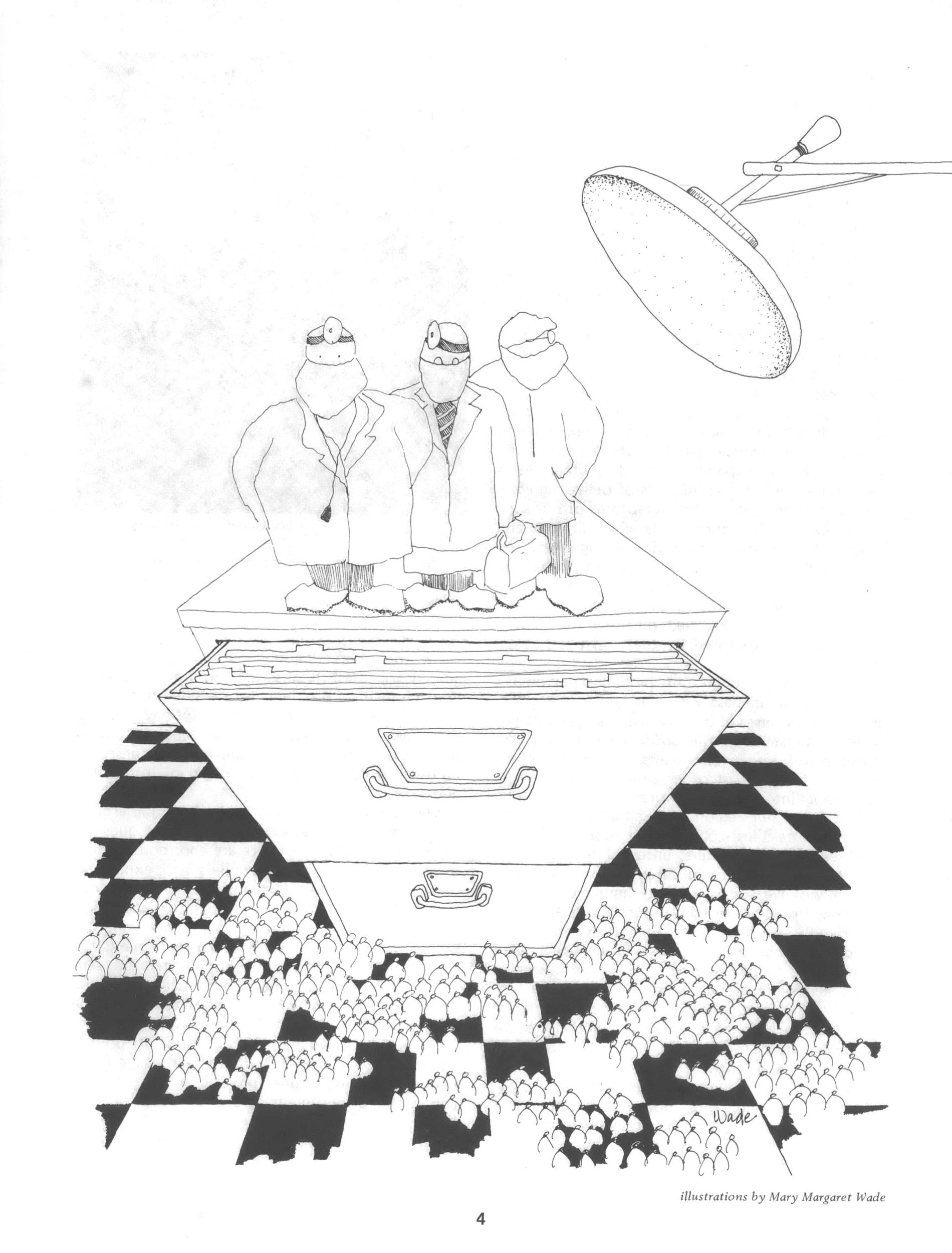

In the spring of 1977, when Southern Exposure began planning this special issue on health care, we invited a number of people to Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee, to discuss the topics we needed to include. By the end of the second day, it was clear that for many of the people in the room, their own training as health care professionals epitomized many of the contradictions and abuses within the system that we had been discussing earlier that weekend. As we went around the room, one person after another described how they found themselves, at first, confused and intimidated, then outraged and oppressed, by their schools’ perpetuation of a health care system built around a polarized provider/consumer relationship. They found themselves forced to make choices between self-advancement and service to people, between obedience to authority and sensitivity to patients, between belief in technical answers and confidence in community control. One by one, they described their experience of fear and isolation that had dominated their years in training, fear that they would crack under the pressure, or “be found out ” and purged from the medical establishment — a fate which ultimately befell several. Those of us from Southern Exposure were deeply moved by these highly personal stories. We knew that even if we couldn’t capture the emotion of the moment, we had to somehow share with a larger audience the insights and spirit of this group of veterans from medical education. Some of the participants, still fearful of retaliation by their “superiors, ’’ did not want us to print their real names. Others went home, interviewed their fellow students and submitted additional comments, some of which are included here. The final, excerpted and edited “round-table discussion’’ provides, we think, a powerful statement on the making of the health care professional in America today.

Among the participants included here are several nurses, black and white, men and women: Cindy Decker, Rich Henighan, Sybil Lewis, Winona Houser, Gloria Wright, Janice Robertson, Ed Hamlett and Rivka Gordon; professors Les Falk and Peter Wood; doctors Henry Kahn and Dan Doyle; and health administrators and activists Maggie Gunn, Irwin Venick, Earl Dotter and Robb Burlage.

Maggie Gunn: I’d like to begin because I am getting my doctorate at the School of Public Elealth at a state university, and the problem there is that they don’t talk about power and the goals of the health care system. What you are taught is that there are certain problems of service and they can be solved by technological formulas. It’s all a question of just making the rounds of administrative techniques which have been borrowed from business schools. That’s what they teach you and I’m at a liberal school. What the health system really is, who controls and who benefits from it, what is the role of the public health people in the community, can you have meaningful community input, can you have non-bureaucratic, nonhierarchical health organizations — all these issues are never dealt with.

Cindy Decker: I have a lot of thoughts about the kind of training I went through, too. I guess the first thing to say is that the education of a nurse at any level is far from pleasant. Nursing students are required to assimilate a tremendous amount of material — anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, psychology, and pharmacology are just the beginning. That is stressful in itself. But worse is the need to be a certain kind of person.

Nursing schools try to mold students, mold their personalities, the way they react to things, everything about the way they are. It happens at every level, from the way you wear your hair to the way you respond to a sexual advance from a patient or another staff member. What kind of deodorant you wear can be very important in nursing school. So can what you do with your little time off, who you live with, and whether you admit to seeking counseling for a personal problem.

Not so many years ago, nurses were trained into complete submissiveness to the doctor and even to their nursing superiors. Nursing schools and hospitals were run on a military model, which is not surprising, since nursing as a trained profession developed to serve the military. Doctors write “orders”; nurses carry them out. Today some of this has changed. Many nursing schools say that they are no longer trying to produce the handmaiden-to-the- doctor type of nurse. They teach their students to refuse orders which they believe to be dangerous or unethical, and they talk a lot about the nurse as an independent practitioner, capable of making independent nursing judgements, even nursing diagnoses.

But in practice, nursing education still fosters obedience to authority. And the hospital structure itself reinforces this teaching. As a baccalaureate student, we were told that we were better than the associate degree nurses, who were probably better than the hospital degree nurses who were better than LPNs who are better than aides. And it really is a “better than” point of view. What that serves to do is to divide all these health workers in hospitals up into little groups so they won’t get together and say, “Wait a minute, we’re all getting screwed in this hospital.” There you are as an RN, you get out in a hospital — my position was a supervisor of the whole level of other people in an extremely hierarchical situation where I, as the young new graduate RN, was supposed to take charge and tell everybody else under me what to do — including those who had been there for years and who knew their jobs. They were supposed to acquiesce to my “authority.”

Of course, I was put through the mill, which I expected somewhat because I had some understanding of the hierarchy and the kinds of pressures on all of us. But most RNs aren’t prepared for the kind of hostility they are going to meet, and so the kinds of separations and divisions that have been set up are perpetuated. People end up being angry at the other staff instead of trying to understand what’s going on. It’s a very hard situation.

Rich Henighan: I went to a nursing school in what was basically a rural county, a hospital program, and it was one of the hardest experiences of my life. I really hated it. I went there because I already had a university degree and I wanted to work in the area: I thought a good way to learn more about health care in the region was to go to nursing school there. And I partly attributed the bad things that were happening to the fact that it was a small hospital program. Then, when I went to a university to do my nurse practitioner program, I found out that wasn’t true, that the same things happened at this prestigious university. It was surprising. Then I learned it happened at other programs; it was normative. There was a definite way of educating nurses that had to do with things like keeping files on them, observing incidents that you performed in the hospital, or didn’t perform, or things you didn’t even know existed. Then, all of a sudden, somebody made the decision that this particular student was not nursing material and then they were given a notice saying you have to take a leave of absence or you have to leave.

I got a note one day from the director which said something to the effect that she had received some complaints that I smelled bad and I should correct that and take a bath, and I should cut my hair. That was the sort of thing that happened, and I remember the way that bothered me as a personal affront. That was the level people were attacked on in nursing school; their personhood was attacked in a very bad way. Your accusors were unknown. It creates all this mistrust; I like this instructor, but maybe she was the one who reported me, or I don’t like that instructor, I bet she is the one who did it.

I guess that’s the thing that bothered me most about the school — the way students were treated by the faculty who were in theory trying to train them to relate to people in a caring, constructive way, to think independently and be creative in difficult environments. Yet everything the faculty did contradicted that theory — in the way they related to students, in the way they disciplined, in the way they structured classes. Someone would come in and lecture and then you had to take an objective test.

Sybil Lewis: Really, that’s it. I don’t mind having a hard instructor as long as they’re supportive, but instead they teach you to be petty and competitive because they really do focus on things like how neat your hair is or the length of your dress.

Winona Houser: The competitiveness is the thing I found to be the most terrible. People just revel in somebody else’s mistake. If the student makes a bad mistake in the hospital, everybody knows about it. And there is always the attempt, if students have been on the floor, to blame any error on them. So you have this pecking order, and again you build yourself up by putting somebody else down. But if we gave each other positive feedback and supported each other, we wouldn’t need to build ourselves up by putting other people down.

Rich Henighan: There were groups of students who did trust each other. The only way that I got through school was that there were two or three other students, and we could sit and talk honestly and know none of that was going to get back to any of the faculty.

Sybil Lewis: The student really is isolated. My instructor didn’t even want to be bothered by me talking to her about my problems. She was busy with law school and didn’t have time to read my progress reports. All the time she was telling me I was doing good, and “Don’t worry about it,” and I would say, “Well, it is not showing up in the progress report,” and she would say, “Oh, don’t worry, don’t worry.” Then she called me in and said she had tossed and turned all night in making her decision, and she thought she had seen improvement in my patients and saw me communicating with my patients and said that was beautiful, but she said that in communicating on paper I was a slow student, but once I catch on, I got it. And if it was up to her, she would pass me, but because of all the bad reports in different areas, it would not be fair to other students if she passed me.

There is a sheet of paper you are supposed to sign that says you agree to the pass or fail, and I wouldn’t sign it. That made her mad, but I wouldn’t agree to her evaluation. So we went to the Dean’s office. It was sad because there was no way the decision was going to be changed. The faculty and Dean all stick together. So it really didn’t matter how you plead your case; you had no input.

Gloria Wright: It would be fine if they wanted to help you by pointing out your weaknesses and facilitating you working with that weakness, but it’s not that. It’s “You’re weak in this area, go work on that, go talk to so-and-so.” All they do is pass you off. It’s like you’re the black sheep and they can’t find a place to put you. I wouldn’t want any of my sisters to go here, except maybe my baby sister who has been in integrated situations for over ten years; she has her own determination and doesn’t let what people say about her bother her any.

Janice Robertson: If you don’t fit in, they’ll use your weaknesses against you. I was called in for a review of my latest progress report two weeks before the end of the semester, and told it was not passing and I could repeat the course after I took a leave of absence. I had received A’s on the midterm and papers before that. The same thing happened to Sybil that same week. The fact that we had gone to the Dean to complain about one instructor having so much power and that I had begun talking to students about the right for a hearing on such decisions, may have influenced the evaluation. There wasn’t any direct proof that my “unprofessional attitude” — working in a community-run clinic, becoming friends with patients — had any influence, but a disapproving eye was felt. That semester nine students were asked to take a leave; seven were black. None of us had flunked the term papers, or tests, but our clinical instructors in a one-to-one setting had told us each that we just wouldn’t make it. That’s where they used our individual weaknesses or vulnerabilities against us. For me, I had trouble with the sight of blood. I was working on it with a counselor, but it was not interfering with my clinical work at that time. But my instructor just said I’d never get over that fear and I couldn’t make a good nurse.

Sybil Lewis: I do find it hard to be black and in this situation. Little things happen all the time. Not long ago, the Dean was speaking at a convocation and said, “It is predominately white, but now we have fourteen blacks,” like “We have our token blacks.” She may not mean anything by that, but why bring it up? It is so cold the way it is said. Anywhere else, it would be an accepted fact: “Of course you have blacks,” but here it is, “Look what progress we have made.”

Rich Henighan: The official line is also that they want men in nursing, and they are glad to have men in nursing. I think it comes out of the belief that the more men who go into nursing, the less it has the “pretty little girl” image. Also, the more men who go into nursing, the higher the salaries go. It is just one more iron in the fire to get the changes they want.

Ed Hamlett: I was a technician for three years before going to school, and I got lots of encouragement to go into nursing. But there is a kind of sexism involved in my work now; it gets manifested in always being assigned to male patients because they don’t trust me or because they sensed female patients wouldn’t like me giving them a bath. Women nurses were assigned to both men and women, so there was a double standard.

Janice Robertson: I think that ties into what we were saying about how division and separations are perpetuated with the nursing ranks. Even the nursing literature is filled with challenges to the old stereotypes of a nurse being incapable of independent reasoning and always subservient to a doctor. There is now a fiercely independent streak among nurse associations, which is in contrast to the team approach and supportive role nurses played, to the very nature of or perhaps the very uniqueness of the nursing role. So not only are the competitive impulses nurtured between doctor and nurses, but also within nursing students themselves and between them and their fellow nursing workers.

Cindy Decker: The changing role of women in general in our society has something to do with this. Strong women are generally working into positions of leadership in nursing. I don’t think they have a very good analysis of why things are the way they are, but at least nurses aren’t just saying “Yes sir,” or “Yes ma’am” anymore.

Peter Wood: Except when you recall the history of nursing and its beginning within the military, the original women who cracked the structure made their reputation as anti-bureaucrats; they so publicized the bad medical care during the Civil War that the generals couldn’t shut them up.

Rivka Gordon: There are all sorts of mixed messages; you’re never exactly sure which way you’re supposed to go. On the one hand, you are supposed to assist the doctor; on the other hand, you are supposed to have the interests of the patients at heart and that’s why you’re different from doctors.

Rich Henighan: The “best nurses” somehow manage to appear to the physicians to be basically making life easy for them, but at the same time somehow manage to provide care to the patients in some assertive way — you didn’t just do the minimal amount. The lesson was to try to find ways, without directly challenging the physician, to find ways to meet patients’ needs that perhaps were not being met.

Ed Hamlett: I remember being told, “Whenever you are doing a sterile procedure, you always take an extra pair of gloves in with you. Then if the doctor breaks sterile procedure, you can tact- fully say, ‘Doctor, I have some sterile gloves here if you would like to change.’ ” So there was recognition that nurses did carry responsibility for caring for patients, and that might mean suggesting that doctors do things a different way or that might mean not giving the medicine in the dosage ordered. It was always very clear though, that we are not colleagues with the doctor; it was pretty clear who was God in that situation and who was not.

Winona Houser: Oh, respect the doctor, he is most holy. They tell you that the doctor should help you, but he thinks you are subservient. When you’re a student following the doctor around in the hospital, they tell you, “Don’t ask him any silly questions.” But if it is something you don’t understand and this silly question is going to facilitate your understanding of the patients’ conditions then I feel like you ought to ask your silly question. They make you feel very humiliated.

Janice Robertson: The whole thing really is a dehumanizing process, and I wish I had realized that before entering nursing school. Persons become objects which you do something to. Patients are identified as the liver in Room 202 or the post-op in Bed 1, to which you do the nursing process to. In a way, the whole mystique about medical and nursing diagnoses is also reinforced, and you’re supposed to believe that you are learning these great secrets that separate you from the rest of the society. I experienced an incredible struggle of vigilance to keep in mind that the actual information about how our bodies function is not some mystery reserved for the privileged few.

Henry Kahn: I’ve been listening to this discussion of the socialization process that goes on in nursing school and comparing it in my mind to what happens to doctors and to my own background. I think for the physician, the important thing is the selection process by which he or she gets into medicine in the first place. It’s a highly personal, self-promoting kind of thing. It may be influenced by family, but it rarely gets beyond the family in terms of community responsiveness, and that’s perpetuated all throughout the training process. You know by the time you get out you’re in it only for you; you know that there is a warm bed that you are making for yourself. Anyone who is interested in health for purposes of community responsiveness is very unlikely to get beyond junior high school as MD material. The selection process starts so early that the candidates who come before the admissions committee at medical school are almost uniformly oriented toward personal advancement. At the moment, there is some required rhetoric about family practice, rural care, serving the under-privileged, and so forth, but the words are illusive.

The MD selection process is so self-centered that everyone who’s in it can be counted upon to accept socialization on their own without petty harassment. By the time they get to professional school, and beyond that to the rigors of internship and residency, the pain is a very traditional kind of pain — excessive maybe, but just long, long hours of very fatiguing work circumstances. Compared to the nurse’s experience, there isn’t much hassle on the juvenile disciplinary level, although that is there for the person who does not toe the line and show some obvious respect. In general, the costs and the duration of education are so great that none but those who are already in a class that’s self-serving can even think about it. There are exceptions — I hope there are some in this room — but it’s hard to know how we might be exceptions fundamentally when you find out where we’re coming from and what we really think we’re going to do and how much can we, despite our intentions, really respond to community interests.

Physician education is limited pretty much to upper-middle-class people, whereas nursing candidates can pretty much come from any class, especially if you consider the hospital programs. There is an alternate channel of nursing that really traditionally has come out of working-class women. Nothing like that in medicine. The worst of it is when occasionally you find exceptions — working-class people who make their way up to the medical admissions committee — their socialization is often stronger than anybody else’s to make it up to the independent self-serving style that characterizes traditional physicians.

Les Falk: I teach at a place, one of the two predominantly black colleges, and certainly there has never been a period of history with enough rich black families to account for admission to Howard University and Meharry Medical College. What has been necessary is holding out the same carrot of succeeding in good income; they offer opportunities for independence which are pretty rare in human life and in return for that, there hasn’t been the graduation of very many allies with social change movements.

Nursing and physician education literally isolate the student into these kind of self-serving, internally competitive structures. I think it is extremely important that there be activities and efforts within the medical school framework, the health system framework, for students to experience the difficulties of people going bankrupt getting commercialized care, to get students out of the nest into real life and attempt to get them in contact with communities. But I think we should be very careful not to confuse a student’s experience with a health fair or community rotation with a real understanding of what social organization, community organization, consumer leadership, what an egalitarian relationship really is. If you want to make a contrast, just take the example of how many faculty members in the US do farm work or factory work in order to learn the conditions of life as our Chinese counterparts would do.

Dan Doyle: I’d like to say a little about my experience of socialization in medical school. I feel that was a very personal struggle for me. A lot of criticism of the process can be made, but the main unifying theme that I can see picks up what Henry and Les are saying about selection and accountability. If you are admitted to medical school, you are not selected by your commune the way you might be in China; you are self-promoting, self-selecting, fighting your way in. And when you get admitted, the one thing that is emphasized to you throughout the whole four years is your importance as an individual. The worst mistake you could ever make would be to submerge yourself in some kind of an egalitarian system or in some kind of a cooperative effort because you wouldn’t really be fulfilling your personal potential.

Anytime you tend to stray off the path, they don’t so much pull out a personal file as hang over your head the possibility that you might be eternally lost because you aren’t proceeding along the path of individual accomplishment. I was thinking there are two camps of people; the cynics and the liberals. The cynics are those people who constantly keep saying, “Oh, you can never do that, I thought that too a long time ago; but I realized that people are all no good, and patients are all out to take advantage of you and sue you. You better just watch out for yourself and get the best job you can.” That’s usually said to you at a time when you’ve been working for fifty or sixty hours straight, so you’re already beaten down and inclined to believe the worst.

Then there are the liberals who make some overtures to social change, but always in a way to support their professional identity or agendas. Like if you’re interested in social change, they don’t say, “Well go work in a factory awhile and see what it’s really like”; they say, “Well you ought to take a year off and get a masters in public health or public health administration.” Because if you are interested in social change, the way to achieve it is through a professional, elitist approach — become a health planner, community medicine, do some research on distribution of health care. In any case, do it in an individualistic way, and that continues on into when you choose your residency — look for the best place, look for the best future for you. So if people finish that system and decide they want to be involved in community health care, they sit down in a situation where they are faced with a community board. Initially, there is a conflict because people come in there with a sense that they are going to do something for that clinic, and with a lot of ideas on how it can be done. Either they fail, or they go through a period of re-education, after years and years of emphasis on the individual’s importance.

Southern Exposure: Why are so many people getting into health? I’d like to hear from the people who are involved in it, what they see as the personal reasons for the increase in so-called health professionals among “socially aware” people. Is it an avenue where in the ’70s you think you can combine the ability to make a living and survive with some sort of social expression?

Dan Doyle: I think it’s because it’s an easier area to compromise. I think it’s an illusion to think that just because you’re involved with health and taking care of and serving people, that it somehow naturally contributes to social progress. A lot of people who are idealistic and who clearly don’t want to be associated with being in big business, or in an obvious expression of the profit system, gravitate to health because it allows them to harbor their idealism a little bit longer.

Rivka Gordon: I don’t think that’s a total picture. I think that the more people know about health as broadly defined, their own health and the communities’ health, the more they can become self-reliant, and the more people become self-reliant the more power people have to make changes in the system as a whole. As long as we have a really unhealthy population, psychologically, physically, housing and education — all those things — then people can be more easily controlled. I don’t see health as only providing medical services at all. In fact, I think that the service aspect of it is one of the parts of it that I have the most problems with, although I am involved with direct patient care; I question that a lot. I think that it’s a way to help people become more self-reliant.

Earl Dotter: I am a photographer who is also concerned about health issues. It seems to me that health is an issue that really is where our capitalist system is vulnerable, particularly in occupational health. We have a cancer epidemic which everyone in this country can identify with. For me focusing on problems of worker illness at this particular time, I think quite a bit of the larger population can perceive what that’s about as their mother, father, or daughter, fall apart in front of them from the diseases that are confronting everyone caused by our industrial society. It seems like it’s a real large area to organize from that affects virtually everyone in this country.

Irwin Venick: It strikes me that there are two parts to the question: one, why is there a gross increase in the amount of people going into health? I think the simple reason is there are a lot of dollars in health, and it’s an expanding work market; you have health planners, health administrators, etc., etc. It’s a growing industry. The more interesting question is two — is there a disproportionate number of political people involved in health? If that’s the question, I think that Rivka is sort of on target cause I think it’s easier for people to make an association between working in some sort of health area and expanding into some sort of political activity than from other areas.

Robb Burlage: I think the contradictory expansion of the medical/industrial complex in the South is a reason why political people would want to relate to it. The resources are there, and the outrages and misuses are there. But the question of how we deal with those contradictions goes back to the personal, political level, to the idealism about our working formations and community advocacy. I think if we’re honest with ourselves, we have to recognize the extent to which we are supporting community health clinics which are trapped, which aren’t able to move beyond the formations they are in, the extent to which we are on the edge of the trade union situation advocating occupational health, but can’t get any further. To talk about taking on the contradictory expansion of the health system sounds idealistic. We have enough trouble just keeping going, keeping the Brown Lung Association supported ora community clinic surviving in the bureaucratic maze. I think this kind of struggle we’re in has to do with the whole political cycle in the country, in which there is not enough mass movement obvious in any area to move people forward and force them to change self-critically and in which people feel they need to be partly protected with a certain amount of professional access or a job security of a kind. I think a lot of people who have been washed up into areas of health activity are trying to be creative in it and shouldn’t be grandiose. One of the nicest things about today’s discussion has been talking about eye-level experiences in medical education, attempts to keep activities going at the community health organizing level, and how to be serious about the overall problems of the health industry’s growth contradictions while helping each other survive. I think this is the balance that has got to be struck if we’re talking about strategy. Otherwise we extol the community experiments on one hand, and we talk about all the alienation we experience in our own medical education on the other hand, and we don’t relate the two. That putting-together is exactly the problem we must face personally and politically with others in this room and in the community at large

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.