This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

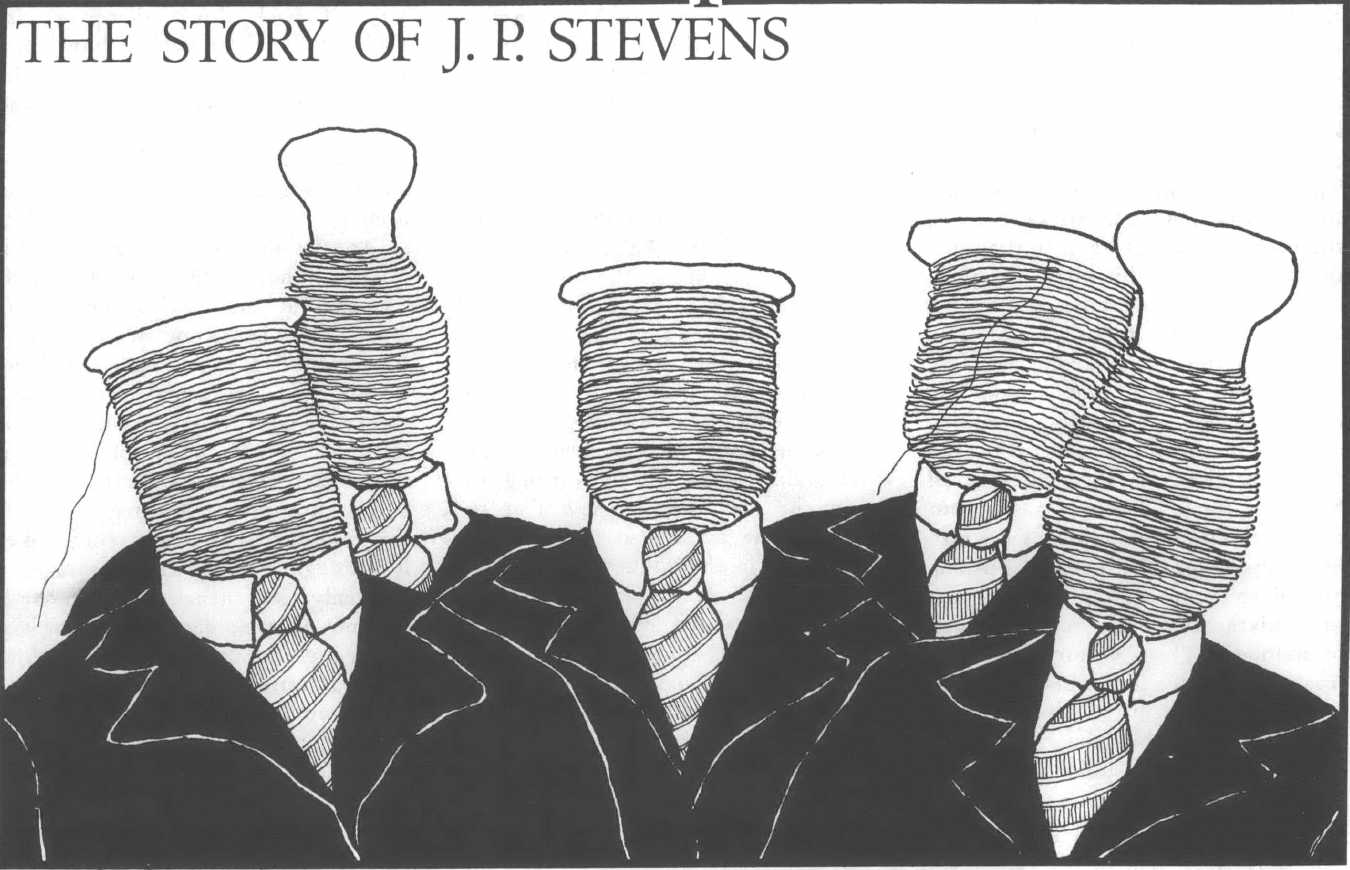

J.P. Stevens takes pride in describing itself as "the world's oldest diversified textile company." In more recent years, it has downplayed the fact that it is also one of America's oldest family-run businesses. As the company grew from one mill in Andover, Massachusetts, to its present eighty-five plants with 45,000 employees and $1.5 billion in sales, it retained many of the characteristics of its founder and his family. Stevens is still controlled by a very small group of carefully selected men; and like Nathaniel Stevens, the company's founder, these modern mill men want to control, as much as possible, everything that affects Stevens' business, including its workers and the communities where it has plants.

Stevens' much publicized opposition to labor unions becomes more understandable, though no less atrocious, in light of this ideological refusal to share power with "outsiders." The company has even refused to obey a string of court orders which have found, among other things, that "with scant regard for the means employed other than effectiveness, Stevens interfered with, restrained and coerced its employees in the exercise of their rights under the labor law, flagrantly, cynically and unlawfully." When workers overcome such coercion and vote to be represented by a union, as they did in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, the company still refuses to bargain with them in good faith. A National Labor Relations Board administrative judge declared in December, 1977, that Stevens "approached these negotiations with all the tractability and open-mindedness of Sherman at the outskirts of Atlanta."

Nevertheless, over the years, Stevens has been forced by outside circumstances and its own greed to change its policies — for example, to open plants in the South, to sell its stock to the general public, to hire black workers.

The Institute for Southern Studies has published other articles on textile workers and the campaign to organize J.P. Stevens (see Southern Exposure, Vol. Ill, No. 4 & Vol. IV, Nos. 1-2). In the following, we focus on the men at the top, the men who established and maintained the company's anti-union policy, the men who owned and directed the company from its beginning in New England to its migration South to its current partnership with the big Wall Street banks and insurance companies.

Captain Nat Starts A Company

J.P. Stevens & Company traces its history back 166 years to the War of 1812 when its founder, Nathaniel (Captain Nat) Stevens, was running a general store in Andover, Massachusetts. According to family legend, the twenty-six-year-old Stevens had spent several years of adventure on the high seas, and had returned home to make his fortune. The War apparently provided just the opportunity he needed. While courting his future wife, he spent long hours talking with her father, a successful mill owner; both men agreed with other businessmen in New England that the War with Britain left America in need of domestic manufacturers of wool cloth. The idea intrigued the energetic and ambitious Captain Nat, and in 1813, with financial assistance from two partners, he converted his father's grist mill into a woolen mill. He called it the Factory Company; it was the first Stevens textile mill, but only one of dozens started by young New Englanders in the early nineteenth century.

Conversations had not made Captain Nat an expert at running a woolen mill, so later that year he hired James Scholfield as overseer. Some relatives of Mr. Scholfield were hired, too. But by 1815, Captain Nat had mastered the details of the business, and he promptly asserted his control over the mill by firing Scholfield and his relatives.

Business boomed during the war. But with the return of peace, British woolen goods flooded the domestic market and many woolen mills went out of business. Captain Nat, however, continued to move forward; he boldly switched to flannel production, becoming the first domestic producer of flannel goods. This daring venture paid off quickly. By 1832, he had gathered enough capital to buy out his last partner and change the name of the operation to the Stevens Company. He continued to build up his investments and expand his influence in New England business and social circles. He soon owned stock in a gunpowder factory, banks, insurance companies, mills, railroads, and several water power associations. He also served a term in the Massachusetts legislature.

By 1852, the editors of The Rich Men of Massachusetts described him thusly: "Started poor. A remarkable specimen of an energetic character. His perseverance yields to no obstacles." His response to the gentle taunting of Abbot Lawrence, a much respected importer of woolen and flan-' nel goods, dramatizes Captain Nat's determined approach to business. In 1820, Lawrence advised Stevens to close his mill and boasted that overseas manufacturers would always produce goods more cheaply. Stevens replied, "As long as I can get water to turn my wheel, I shall continue to run my mill." Ironically, Lawrence later asked Stevens to join him and other textile leaders in establishing the Merrimack Water Power Association, a lucrative privately-owned enterprise that made possible the development of Lawrence, Massachusetts, as a textile manufacturing center.

As the Stevens company grew in the 1850s, Captain Nat initiated the longstanding tradition of bringing his immediate family into the business. His brothers, George and Horace, became partners as well. But not all the Stevens family entered the business. Nat's eldest sons, Charles and Henry, left Andover to begin businesses of their own after incurring the wrath of their father. Charles had gone on a lengthy and expensive vacation to Europe against his father's will, and Henry had worked for a rival mill in Andover when it undertook a vigorous price war with Captain Nat.

Nat Stevens started another family tradition — expansion. He purchased a second mill, making him the only flannel manufacturer in the United States owning two mills (see box on next page). The Civil War brought so much business that the mills often ran twenty-four hours a day. As business prospered, the aging Captain Nat became less and less involved in the company's operations. He died one month before Appomatox, at the age of eighty. He left behind a personal fortune worth over $400,000 which helped the family survive the glut of textile goods following the end of the Civil War and the resumption of British imports. The future for his heirs looked even rosier after Moses, Captain Nat's son, accidentally discovered an innovative 60/40 blend of wool and cotton. The new product helped the company weather the postwar depression that peaked in 1873. Getting the jump on his competition, Moses also streamlined the marketing of his goods. Traditionally, textile mills marketed their products through a number of selling or commission houses; but in 1867, Moses placed the entire Stevens account (except the old standby, flannel goods) in the hands of Faulkner, Kimball & Co. Pleased with the results, Moses handed over the rest of the account three years later.

The marketing agents of textile goods became increasingly influential in the late 1800s. They had a keen sense of what would sell and could provide credit for the manufacturers they represented. As the commission houses developed into the most powerful part of the business, the Stevens family began asserting its policy of close, personal control in this area. The family enlisted Henry Page, a long-time neighbor and friend, to become a partner in the Faulkner, Kimball firm and to look after the Stevens account. The firm soon became Faulkner, Page & Co., and in 1883, John Peters (J.P.) Stevens, Sr., (Moses' nephew) joined its Boston office.

Shortly thereafter, J.P. Stevens moved to New York and took charge of all the Stevens' mill goods. By 1899, when Henry Page died, the family was no longer satisfied with the services of the selling house. They were also becoming alarmed by strong competition from the conglomerate American Woolen Company. Since J.P. Stevens had acquired enough experience to run his own selling house, the family encouraged him to leave Faulkner, Page & Co. and begin his own business. On August 1, 1899, the day after his son, Robert T. Stevens, was born, he opened a new selling house with twenty-one employees, $25,000 in capital and two accounts: M.T. Stevens & Sons, and A.D. Gleason, another close family friend and wool manufacturer from Gleasondale, Massachusetts. This was the beginning of J.P. Stevens & Co.

By 1907, when Moses Stevens died, the two branches of the Stevens family controlled six mills and a selling house, which were each incorporated "for the permanency of the business . . . (not) for building up large fortunes by watering the stock." Like his father, Moses Stevens had ably practiced the policy of influence through corporate and political involvements: he was president of Stevens Linen Works; trustee of the Andover Savings Bank and the Merrimack Fire Insurance Co.; director of the National Exchange Bank of Boston; and served terms in the Massachusetts General Court, State Senate, and the US House of Representatives, where as a powerful member of the Ways and Means Committee he was instrumental in passing new wool tariff legislation favorable to the textile industry.

His devotion to the business matched his father's. Once, while traveling by buggy to the Haverhill Mill, Moses ran into a brisk thunderstorm. When his son, Nathaniel, suggested they stop and seek shelter, Moses replied, "Nat, when you are going anywhere on business, never pay any attention to the weather." His success at expanding the family business can be measured by the fact that, until the formation of American Woolen in 1899, M.T. Stevens was the wealthiest and largest woolen manufacturer in America.

He left the company in equally determined hands, but now there were two strong family figures. In Massachusetts, Nathaniel continued to run the New England mills in the family tradition, expanding whenever possible and replacing his father as a leader among New England industrialists. In New York, cousin J.P. Stevens rapidly built up the selling house and became involved in numerous financial institutions and manufacturing associations.

The new conditions did not threaten family unity, however, as biographer Lloyd C. Ferguson notes:

The connection between these concerns was still further cemented by J.P. Stevens' family loyalty. Incorporation in no way diminished family control, and the leaders of the family showed no inclination to join the huge woolen combination that constituted their major competitor.

The real future of the textile industry, however, lay in the South, and J.P. Stevens, Sr., was one of the first to recognize the region's potential need for credit and marketing agents. He criss-crossed the South for twenty years, looking for new cotton mills that would sell cloth through the Stevens commission house and that seemed healthy enough for his own investments. He was aided in this effort by cousin Nat, who established strong contacts with Southern mill men in his own extensive travels. Mr. Nat provided the Southern mills with the capital to expand and in the process garnered new accounts for J.P. Stevens' commission house.

Their investment gave the Stevens family a significant voice in the affairs of the Southern mills; and since the Southern mills had little contact with their buyers, they were dependent on the commission house to tell them what to produce. Stevens simply followed the practice of their competitors: they encouraged the mills to produce at maximum capacity, ensuring a steady flow of substantial commission fees; and they convinced the mill owners to pay off loans before paying dividends, ensuring the safety of the Stevens family investments.

By the end of the 1920s, the changes in the textile industry were apparent. The newer, more efficient Southern mills were outproducing the older New England mills. Although New England mills still had more spindles, Southern mills had sprung up at an astonishing rate, especially after World War I. Southern businessmen, usually spearheaded by a local group of wealthy investors and aided by a commission house's credit arrangements, would build a mill in a small village and begin attracting an eager workforce from surrounding farms. The local government and power company provided tax incentives and cheap power, and the isolated nature of the towns combined with the depressed local economy and pro-company government to make union organizing all but impossible.

J.P. Stevens, Sr., soon became only one of many Yankees anxious to exploit the region's "textile opportunity." In fact, the first wave of revolt by mill workers in 1929 at places like Elizabethton, Tennessee, and Marion and Gastonia, North Carolina, broke out largely in reaction to the introduction of Northern-style "scientific" management techniques known as the speed-up and stretch-out. But the strikes were violently crushed, and the system of milltown paternalism - like the system of plantation paternalism before it — was forcefully preserved. J.P., Sr.'s investments remained secure; his vision that higher profits could be squeezed from the South proved correct. The final display of his uncanny feel for market conditions came with his death two days before the stock market crash of 1929.

His sons, J.P., Jr., and Robert, were left with control of J.P. Stevens & Co. Throughout the Depression, they carefully expanded both the selling house and their investments in selected Southern mills. By 1939, they had brought the sales volume of the company to $100 million, putting it among the top five commission companies in the business. The brothers also recognized the importance of having well-managed suppliers who could turn out the right product at the right time. Like other marketing agents, this realization led them to want more control — and outright ownership — of the mills they sold for, not just those run by their cousin Nat.

When World War II erupted, the company was in a good position to take advantage of the tremendously increased need for textiles. J.P. Stevens & Co. funneled lucrative government contracts to the family's New England mills and to those it controlled or represented in the South. Of course, it helped to have Robert Stevens appointed a colonel in the office of the Quartermaster Corps and serve as deputy director of purchases in charge of federal contracts worth tens of millions of dollars (Stevens was one of the top five textile contractors in the war). In his new position, Colonel Robert also made a number of friends who would help the company for decades to come (see below).

1946: The Crucial Year

The year 1946 proved to be a critical one for the growing Stevens empire. Nathaniel Stevens had run the New England mills quite well, adding four new mills in his forty years of running the company. He also had gained much influence in the New England financial community, serving as president of the Andover Savings bank, a director of the First National Bank of Boston, and a key figure in the American Wool Institute and the National Association of Woolen Manufacturers. But when he died in 1946, no single heir seemed capable of managing the New England mills or settling the huge tax debt on Nat's estate.

At the same time, the Stevenses at the New York commission house needed capital to buy their own chain of Southern mills. They knew the normal postwar burst of consumer spending would mean profits for the textile companies that could integrate manufacturing and merchandising operations, and thereby respond quickly to changes in market demands. One other factor contributed strongly to their interest in moving South. In 1940, the CIO singled out M.T. Stevens & Sons as a focal point in their drive to organize the woolen and worsted industry. The general shortage of workers during World War II helped the campaign move forward swiftly; the Stowe Mill voted in the union in 1940. The Peace Dale and Hockanum Mills followed shortly. Workers in the Stevens mill went for AFL representation in 1943. Finally the Pentucket employees voted in the CIO in 1945. And although the unions had lost elections in the other plants, they persisted in their organizing attempts. Thus, five of the family's ten New England mills were quickly unionized and the others seemed ready to follow. It is not surprising that J.P., Jr., and Robert were looking South with eager eyes.

So in 1946, the two sides of the Stevens family decided to reunite and join a group of Southern mill owners for one of the biggest textile mergers in history. In a transaction valued at $50 million, M.T. Stevens & Sons, J.P. Stevens & Co., and eight Southern textile firms (all clients of the Stevens commission house) merged under the name of J.P. Stevens & Co., Inc., with Robert Stevens as chairman and J.P., Jr., as president. The former owners each received stock in the new company equivalent to their stake in the old firms. In addition, the new company sold stock publicly on the New York Stock Exchange to raise a pool of working capital. When the deal was completed, the Stevens family held 40 percent of the stock — giving them the largest single block of votes in running the company, and thus effective control of a company twice the size of their previous assets. The number of plants directly controlled jumped overnight from ten mills to twenty-eight mills with nineteen of them in the South, largely in the Greenville, South Carolina, area.

Stevens did pay dearly for the financial privileges gained by the merger; they had to swallow their pride and allow outsiders to own part of the company for the first time since 1832. From two family-owned businesses, they expanded into a public corporation which issued stock traded on the open market. A majority of the new stockholders were Southerners, and many of the old mill owners became officers and/or directors of the new corporation. Of the twenty-three directors named in 1946, more than half were Southerners. However, the Stevens brothers kept the upper hand by having the new directors establish a three-man administrative committee responsible for making vital corporate decisions between the board meetings. This committee consisted of Robert Stevens, J.P. Stevens, Jr., and William Fraser, treasurer of the predecessor company since the 1920s and virtually an adopted member of the Stevens clan. Even though the Southern directors and officers were given many responsibilities in coordinating manufacturing, the crucial issues of finance and marketing remained in the hands of the Stevens family and their old associates.

The Southern Connection

Among the new group of Southern directors was a collection of men that Stevens had carefully courted for years. Their names read like a Who's Who in Southern textiles. J. E. Sirrine and Alester Furman of Greenville, the two men most credited with making that city the hub of the Southern industry, stand out. The aging Sirrine, head of the textile engineering firm of J. E. Sirrine & Co., sat on the boards of twenty-six mills. He had frequently joined with Furman, an insurance, real estate and investment broker, to recruit the contractors, investors and distributors necessary to open a new mill somewhere in the Southeast. Both men were also directors of banks, railroads, and power companies in the Carolinas, making them key allies for the Stevens move to the South.

William and S. Marshall Beattie, Ramond C. Emery and R. E. Henry, all of Greenville, were other new additions to the new J. P. Stevens board of directors, and they received a total of 47,000 shares of stock in exchange for their interests in five of the eight Southern mill companies absorbed. Norman Cocke, president of the Duke Power Company, was also put on the board, since his company owned the newly acquired Republic Mills. (It was common practice for electric utilities to encourage a mill to locate in their territory by buying some of the mill's stock. Buck Duke made a special habit of this practice and eventually owned parts of mills all over the Carolina piedmont.)

The two Southerners who became most involved in the day-to-day management of the new company were the Carter brothers, Wilbur and Harry, of Greensboro, North Carolina. They received over $2.5 million in stock for their interest in the Slater- Carter-Stevens chain, and for the next twenty years, they vigorously helped Stevens acquire new Southern mills. By 1963, the number of plants had nearly doubled to 55, with most of them in the Carolinas. Another key figure in this phase of expansion was John P. Baum, a Georgian and former mill manager whom Robert Stevens had met in the Quartermaster Corps. He joined the company after the war and became the prime mover in transferring Stevens' wool and worsted manufacturing to Dixie.

Throughout the twenty year period following World War II, the Stevens method of expansion (shared by other emerging giants) was two-fold: (1) close down antiquated or unionized shops in the North and bring machinery to new mills in the South; and (2) buy out existing Southern mills to increase production of a certain product line or to enter a new line. Demand for textile goods was enjoying its longest boom in history, so the object for producers was to control as much productive capacity as possible and to gain as big a share of the market as they could through acquisitions and diversification into new products. In addition to being cheaper than modernizing Northern plants or building new ones from scratch, the two-pronged expansion method allowed Stevens to blame the unions for its exodus from the North and to buy into well-established, pro-textile local power structures in the South.

The rapid shift of woolen and worsted production to the South illustrates the pattern. In 1946, Robert Stevens sent John P. Baum southwards on a site-hunting junket. Stevens soon bought the Hannah Pickett mill in Rockingham, NC, and converted it to woolen goods production. They also purchased a Navy plant in Milledgeville, Ga., and converted it to woolens, and commissioned Charles Daniel to build a large plant just down the road in Dublin, which was completed in 1949. In each of these locations, the company was cordially greeted by the local leaders. For instance, in Rockingham, they were given a long-term contract for a supply of cheap water.

Once these mills were operating, Stevens could close down its outdated plants in New England. In Rockville, Connecticut, they doubled production quotas for their Hockanum Mill employees, forcing the union to strike to protect their contract. On a visit to the plant, J.P. Stevens, Jr., attempted to justify the stretch-out to the local paper: "That is the situation in the New England mills in general; a man does not produce nearly as much, we believe, as he might and as he could without being asked to make any undue effort."

Ten weeks into the strike, during which Stevens refused to bargain on the disputed issues, Stevens announced they would close the plant. Allen Goldfine, a millionaire mill owner from New York, offered to buy the plant for $1 million, but he found the company unwilling to sell for any price, despite their promise to the people of Rockville to sell if they received a reasonable offer. He told the Hartford Times:

I want to buy the plant but I’m getting the runaround .... The company will not give me, a prospective buyer, an inventory of the machines and equipment in the plant. They will not even tell me how much insurance there is on the mill — and they say they want to sell it.

Eventually Stevens turned down Goldfine's offer and liquidated the plant, taking most of the mill's machinery to the South and laying off some 1300 New England workers. The company's message that the union had "caused" the closing was passed on to the Southern textile workers.

The New South

The main reason it was cheaper to move South than to modernize and pay workers a decent wage was the proindustry atmosphere created in the Carolinas by the powerful Southern allies of the Stevens. J. E. Sirrine, S. Marshall Beattie, and Alester Furman characterized the first generation of textile pioneers, but a new generation was making itself known. J. P. Stevens consciously placed men from this new breed of Southern textile enthusiasts on its board of directors well into the 1960s.

One example of the new-style leader was Robert Gage, a banker in Chester, South Carolina, chairman of the Aragon- Baldwin Mills when it merged into J. P. Stevens in 1946. He served on Stevens' board of directors from that year to his death in 1968. As a prominent banker, an advisor to several state government agencies and director of the Federal Reserve Board, Gage helped make credit available to expand the textile industry. And as chairman of the Public Works Department of Chester, he pushed through a modern water-sewage system that helped the local Stevens plant and that became a model for other communities.

Perhaps the archetype of this new generation of Carolina businessmen was Charles Daniel, founder of the South's largest construction company (until recently) and director of Stevens from 1953 to his death in 1965. His Daniel Construction Company, based in Greenville, built the first three Southern mills Stevens constructed after World War II and remained their most frequently used construction firm. He was personally responsible for convincing several wool processors to locate in South Carolina and got the port of Charleston equipped to import wool — two factors which were vital to Stevens' relocation of their woolen and worsted manufacturing described above. A close friend of Bob Stevens, Roger Milliken and other top industrialists, Daniel energetically recruited national companies to relocate to South Carolina, offering a complete package that included building, railroad siding, access roads, sewage and water hook-ups, employee housing, utilities and tax incentives. More importantly, Daniel and other businessmen engineered the replacement of the agrarian-dominated South Carolina legislature with what Fortune magazine called "a government conspicuously friendly to industry." Through their efforts, the legislature enacted a rightto- work law, changed the method of funding public education from county property taxation to a regressive sales tax, eliminated the franchise tax on out-of-state corporations, and exempted from the sales tax all machinery used in processing finished goods — all programs that helped the growing textile giants at the expense of the average citizen and worker.

The creation of a pro-textile South by men like Charles Daniel helped not only Stevens but the entire industry. At the same time, the industry received aid at the national level from Southern congressmen who identified protecting textiles with protecting democracy. For instance, after the first National Labor Relations Board ruling in 1966 that found Stevens guilty of illegally firing workers for union activity, Congressmen William Jennings Bryan Dorn and Mendel Rivers of South Carolina and William Tuck of Virginia hastened to the floor of the House to condemn this "attack on our free enterprise system." Tuck hinted of darker implications, stating that the Labor Board had "undoubtedly become exposed to the methods employed by Communists." When the union asked the government to cancel Stevens' military contracts because of their labor law violations, House Armed Services Committee chairman Rivers rushed to their defense, sending telegrams to President Johnson and the Department of Defense expressing his disapproval and strongly defending the company. The contracts were never cancelled.

Stevens' influence with Southern legislators also paid off on the local level. A 1975 investigation of Stevens' property tax records in Duplin County, North Carolina, revealed that Stevens had underpaid its taxes by over $250,000. It was also discovered that their lawyer in Duplin County was David Henderson, US Congressman from the district. As the Raleigh News and Observer tactfully stated, "Henderson's moonlighting gave an added gloss of respectability to the undervaluation of the Stevens properties."

By linking itself with both the old and the new of the Southern elite — bankers, industrialists and political leaders — Stevens laid the groundwork for uninterrupted growth. But in the mid-1960s, another dramatic shift began to take place in the industry, a shift as important as the one that had brought J.P. Stevens, Sr., to the South a half century before.

Courting the Wall Street Elite

By the mid-'60s, industry was becoming more dominated by the largest companies, the ones that could command a significant portion of the market in several product lines simultaneously. For Stevens, that meant getting the capital to expand existing lines in consumer goods like sheets and towels, while also purchasing plants that made new lines like hosiery and elastics.

Such huge sums could only come from the biggest Wall Street banks and insurance companies. And rather than sell more stock, which would mean bringing in more owners and further decreasing the Stevens family ownership, the company decided to borrow money. In 1965, it got a $30 million loan from New York's Irving Trust; in 1967, it borrowed $59 million from Metropolitan Life Insurance Co.

To keep getting that kind of money, Stevens knew it needed more friends on Wall Street. In fact, the Wall Street banks and insurance companies loaning money to Stevens also wanted a "closer relationship" — they wanted their agents sitting on Stevens' board of directors so they could see what was happening to their money. In 1966, a partner in the Wall Street brokerage firm of Goldman, Sachs & Co., who had put together several multi-million dollar deals for Stevens, was put on the board. Ironically, this man, Sidney J. Weinberg, Jr., filled the vacancy on the board created by the death of Charles Daniel, the man who had helped so greatly in integrating Stevens into the Southern power structure.

Weinberg comes from a family that has long been prominent in the financial and cultural affairs of New York. His father, another partner at Goldman, Sachs & Co., was the financial wizard behind Henry Ford's expansion and the creation of the Ford Foundation as a way to keep the Ford estate from the government's taxmen and the Ford company in his children's hands. Today, Weinberg is the chairman of Stevens' Audit Committee, overseeing the financial affairs of the company. His firm of Goldman, Sachs & Co. still handles Stevens' major deals with Wall Street investors. He has proved an appropriate person to help make the financial, political and even cultural contacts necessary to transform Stevens from a conservative, family-dominated business to a conservative alliance of family and Wall Street running a billion dollar, international corporation.

During this period, Stevens family members were also extending their connections within key New York financial circles. Robert T. Stevens had long since been a prominent figure in industry, serving as a director of General Electric, New York Telephone, and other major corporations. He also headed the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and later served as a director of Morgan Guaranty Trust. His brother, J.P., Jr., sat on the boards of many major institutions, including the New York Life Insurance Company and Manufacturers Hanover Trust. In the early '70s, Robert's son, Whitney, joined the advisory board of Chemical Bank, and the new president and later chairman of J.P. Stevens, James D. Finley, was added to the board of Manufacturers Hanover Trust and New York Life. It should not be surprising, therefore, that in 1972, Stevens borrowed $30 million from Morgan Guaranty, Chemical Bank and Manufacturers Hanover — three of the top five banks in the country. Business Week described the tight group running the company as "clubby Wall Street types," who remained "aloof" from the public.

The ties continued to get stronger. In 1974, Stevens borrowed another $18 million from Manufacturers Hanover and $50 million from three insurance companies, including New York Life. That same year, the chairman of New York Life — R. Manning Brown — replaced Duke Power's D.W. Jones on the board of Stevens. R. Manning Brown was also an influential director of Morgan Guaranty Trust, an important connection Stevens wanted preserved after Robert T. retired from the bank's board that year. In 1975, another New York financial leader, Virgil Conway, chairman of the prestigious Seaman's Bank of Savings, was added to the board of Stevens. Stevens also brought two top Wall Street veterans into its management: Ward Burns, who had supervised the Rockefeller family's European investment, became controller; and Wyndham Gary, member of a leading corporate law firm, became treasurer.

The crowning proof that a tightly knit club held the reins of the company came in 1976 with the appointment of David M. Mitchell to the board to fill the vacancy left by the death of J.P. Stevens, Jr. Mitchell, the chairman of Avon Products, maker of women's cosmetics, is no stranger to other Stevens' directors. R. Manning Brown is a director of Mitchell's company, and in turn, Mitchell sits on the board of Brown's New York Life, along with Stevens' chairman, James Finley. Mitchell also joins Finley on the board of Manufacturers Hanover Bank. Thus, by bringing Mitchell onto Stevens' board, the company replaced a family member with a man from the equally tight Wall Street family that is anchored by New York Life and Manufacturers Hanover, two of the biggest lenders to Stevens.

No one suggests that Wall Street now totally controls the company. But a transition is clearly apparent. The only remaining Southern board member is Alester G. Furman, III. And, like his grandfather before him, he is so important to Stevens' foothold in the Southern business elite, and particularly in the aristocracy of Greenville (where Stevens has 22 of its 85 plants), that he will likely remain on the board for many years.

Preserving the Family Tradition

The shift to the domination by Wall Street types has been slow, and Bob Stevens has been careful to ensure that the Stevens family retains the strongest voice in company decision-making. Much more than his late brother, J.P., Jr., Bob Stevens has been responsible for guiding the company since World War II. And he is very aware of the family heritage; as he said when being confirmed as President Eisenhower's Secretary of the Army, "I am steeped in sentiment and tradition with respect to the company that bears my father's name."

He has followed closely the traditions of the Stevenses, reflecting the same drive and determination that have characterized the leaders of the company since the days of Captain Nat. As Bob Stevens once said, "We go to the marketplace and attempt to find out what the public wants. If the public wants straw, we'll weave straw." His aggressive brand of salesmanship often undercuts his sentimentality; as a company executive once noted, "Bob Stevens would close even the North Andover mill (Captain Nat's original mill) if it didn't make a profit; he isn't running any museums." Indeed, Stevens did close the plant in 1969.

He has also consistently adhered to the policy of tight family control over all the operations of the company. This policy has led to the staunch antiunion stance which has brought Stevens into the public limelight. (See "Stevens vs. Justice," Southern Exposure, Vol. IV, Nos. 1-2, pp. 38-44.) Just as Captain Nat fired James Scholfield to gain total control of the plant, the present-day Stevens company has fired people who advocated unionization. Bob Stevens maintains that the union is a third party, and that "a third party can serve no useful purpose." He contends that the problem has not resulted from the actions of the company, but from the influence of the union, which has disrupted the "unusually fine relations" the employees have with the company. "Look, we don't feel a union is necessary," Bob Stevens told a reporter. It is this insistence that has led to the company's unfair treatment of its employees (see box) and to its reputation as "the number one labor law violator."

Now in his late seventies, Bob Stevens clearly wishes to pass on the company's control to a group of trusted men who, if not related by blood, are at least related by philosophy. He has certainly found his personal successor in James Finley, who, despite his Georgia upbringing, is a throwback to the ways of Captain Nat Stevens; as Business Week observed, Finley “reflects closely the New England founders' congenital conservatism." Chairman of the Board Finley and Chairman of the Executive Committee Bob Stevens worked closely together to restructure Stevens' corporate organization in the early '70s. Although he officially retired in 1974, after fifty-three years with the company, Bob Stevens is still often seen entering Stevens headquarters to put in a hard day's work.

Another Stevens still figures prominently in the direction of the company: Bob's oldest son, Whitney, the current president. Whitney has followed the family tradition of gaining access to powerful business circles by involving himself heavily in financial institutions and manufacturing associations. Brought up in one of the toughest divisions of the company, woolen manufacturing (Bob Stevens' own love), Whitney seems destined to become the next chairman when Finley reaches retirement age in 1981. It is more than likely that he will provide the same leadership that has characterized the company under James Finley and Bob Stevens. As one company executive stated, “Finley and Whitney Stevens think just like Bob does.''

The tight control of Stevens family and friends will likely continue unless there is some protest from the Wall Street directors. Such an event would not be unprecedented; last year alone, the chief executives of twelve of the top 500 companies in America were fired by their boards of directors because they did not perform well enough. And it was usually the outside directors who initiated the move to change managements.

But the Stevens family has shown an amazing resiliency and strength through 165 years of operation. With powerful family control at the upper echelons of management, and with the family's large block of stock (in 1971 they still owned over 20 percent of the company's stock), the Stevenses are likely to exert a considerable portion of their historic domination over the billion dollar Stevens corporation.

Tags

Jim Overton

Jim Overton, a board director and former staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies, is publisher of the North Carolina Independent. (1986)

Jim Overton is associate publisher of The North Carolina Independent, a progressive statewide newspaper — and a veteran of six-and- a-half-years with Southern Exposure. (1985)

Jim Overton is a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1983)

Jim Overton, a founding member of the Kudzu Alliance, directs the Energy Project of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1979)

Bob Arnold

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.