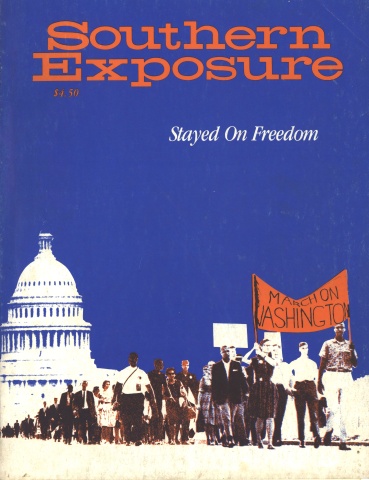

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

On Friday, December 2, 1955, readers of the Montgomery Advertiser who paid close attention to the local crime stories saw this item as they sipped their morning coffee:

NEGRO JAILED HERE FOR “OVERLOOKING” BUS SEGREGATION

A Montgomery Negro woman was arrested by city police last night for ignoring a bus driver who directed her to sit in the rear of the bus.

The woman, Rosa Parks, 634 Cleveland Ave., was later released under $100 bond.

Bus operator J.F. Blake, 27 N. Lewis St., in notifying police, said a Negro woman sitting in the section reserved for whites refused to move to the Negro section.

When officers F.B. May and D.W. Mixon arrived where the bus was halted on Montgomery Street, they confirmed the driver's report.

Blake signed the warrant for her arrest under a section of the city code that gives police powers to bus drivers in the enforcement of segregation aboard the buses.

Two days later a boldly displayed box appeared on the front page of the Advertiser, its headline announcing: “Negro Groups Ready Boycott of City Lines.” Joe Azbell, then the paper’s city editor, wrote in the first paragraph of the article that a “topsecret meeting of Negro leaders” had been called for Monday evening at the Holt Street Baptist Church. The rest of the article reprinted almost the entire text of a leaflet being distributed by black leaders calling for a one-day boycott of the bus lines.

The “top-secret meeting” mentioned in Azbell’s article became a mass meeting that launched not only the Montgomery bus boycott, but also the modern Civil Rights Movement and the career of Martin Luther King, Jr., as one of its principal spokespeople.

E.D. Nixon, the boycott’s organizer, was a protege of the late A. Philip Randolph and a leader in the Alabama section of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters that Randolph founded. He was a consistent, often solitary, voice against the oppression of blacks in his home state of Alabama and his native Montgomery. Nixon knew the arrested woman well. Rosa Parks had been secretary of the NAACP’s Montgomery chapter during some of the many years he served as its president. She was, he says, a “hard-working, God-fearing and respectable lady in the community,” and he knew he could organize a movement of support in response to her arrest. Nixon posted a property bond to secure her release from jail pending trial and asked attorney Clifford Durr to represent her.

There was a young minister in town — Martin Luther King, Jr. — about whom Nixon had heard good things. Nixon had asked him to speak to an NAACP meeting in July, 1955. “As I listened to him speak,” Nixon says, “I knew he could be a leader. I turned to my friend and said, ‘I don’t know how I’m going to do it, but one day I’m going to hang him to a star.’”

Five months later, after Mrs. Parks’ arrest, Nixon got the community leaders together and they formed the Montgomery Improvement Association to boycott the bus company. He persuaded the others to appoint King head of the new organization. “I had to show him the ropes of how to organize. But King did a good job as leader and he spread the word about the boycott. He had an incredible ability to communicate with the audience,” says the 81-year-old Movement veteran.

It should be noted, though, that it was a woman who made the decision that day to keep her seat and defend her human rights. She wasn’t the first; others before her had refused to bow to the Jim Crow laws. But Rosa Parks, tired from her day’s labor, made her move at a time when conditions had jelled and could sustain a movement to support her. A lot of people were tired — and when she kept her seat, she kept it for millions; she was jailed for millions; and ultimately millions would respond.

Here, E.D. Nixon and two women, a black and a white, good friends who have seen and worked for many of the changes growing out of the Movement spawned in Montgomery, reflect on its beginnings and speak of some of what has transpired since. Johnny Carr has been president of the Montgomery Improvement Association for the past 13 years. Virginia Durr has been working for progressive causes in the South since the labor struggles and New Deal reforms of the 1930s.

E.D. NIXON

Rosa Parks and I went back together about 12 years—she did volunteer work for me as secretary to the NAACP. The first thing in anybody’s mind if they saw the police arresting Rosa Parks was to call me. And when they called me, I wasn’t at my office, but the man next door to my office put a note on my telephone to “call Mrs. Nixon, it’s urgent.”

When I came back, I saw it and I called Mrs. Nixon and she said they had arrested Mrs. Parks. I said, “What for?” She said, “I don’t know. Go get her.” As if I could just go get her. So I called down to the jail and the guy told me it was none of my business, and he cussed me.

I had to find out what the charges were, so then I called Clifford Durr and told him about it, and he called down there. He called back and said, “Mr. Nixon, Mrs. Parks is charged with violating Alabama’s segregation law.” And I said, “I’m going down there and make bond for her.” He told me how much the bond would be — $100 — and told me he would go with me. I went by and picked him up and by the time he got down to the car, here comes Mrs. Durr running, and so the three of us went down to the jailhouse, we got her out and carried her home. We asked about using her case as a test case. And she agreed.

I got up the next morning at five o’clock and started calling people. I called Ralph D. Abernathy, and he said, “Yeah, Brother Nixon, you know I’ll go along with you.” And then I called the Reverend H.H. Hubbard, and he said, “Yeah, Brother Nixon, I’ll go along with you. I’ll get ahold of Ab and we’ll help you call the rest of the ministers.” I said, “That’ll be fine.”

Then the third person I called was Martin Luther King. He said, “Brother Nixon, let me think about it awhile and call me back,” and I called him back. He said, “Yeah, Brother Nixon, I decided, I’m going to go along with you.” And I said, “That’s fine, because I called 18 other people and I told them they’re going to meet at your church this evening.”

And so they met down there that evening. I wasn’t there - I had to go to work — but they didn’t get anything done. That was Friday, December 2. So I called Joe Azbell and I told him about it. I told him, “Joe, you got a chance now to do something decent. If you want to do it, I’ll give you a hot lead.” He said, “I’ll tell you what, if I can’t write something to help you all, I won’t even write it at all.” He came over and I told him about it, and he wrote the story [the one carried on the newspaper’s front page Sunday morning giving the place and the time of the “secret meeting.”]

That story really helped bring the people together. I called the ministers that morning: “Good morning, Reverend Sir, good morning,” I said. “Have you read the paper this morning? Have you noticed Joe Azbell’s story?” I said, “Take it to church with you, tell the people about it, tell them we want 2,000 people at Holt Street Baptist Church tomorrow night.”

If we didn’t have 7,500 people out there, we didn’t have a soul. We filled up the church, and all out in the streets. That was a mass meeting. But the ministers were scared to death; they didn’t want their names to get out. And I told them they were talking like little boys.

Now this is from Stride Toward Freedom, by Martin Luther King, Jr., talking about the first mass meeting. He says, “After a lengthy discussion, E.D. Nixon rose impatiently. ‘We are acting like little boys,’ he said. ‘Somebody’s name will have to be known, and if we are afraid, we might just as well fold up right now. We must also be men enough to discuss our recommendations in the open. This idea of secretly passing something around on paper is a lot of bunk. The white folks are eventually going to find it out anyway. We better decide now if we’re going to be fearless men or scared boys.’ With this forthright statement, the air was cleared. Nobody would again suggest that we try to conceal our identity or avoid facing the issue head-on. Nixon’s courageous affirmation had given new heart to those who were about to be crippled by fear.”

E.D. Nixon went on to spend most of his time during the next year raising the money and promoting cars for the car pools that helped sustain the bus boycott. Money and station wagons came from all over the country, from individuals and groups, especially labor unions. Nixon points with particular appreciation to help from the sleeping car porters, the auto workers and the garment workers unions. The Montgomery black community dug deep into their own pockets as well. And help came, too, from some local whites:

All white people weren’t against the bus boycott. There were the Durrs, of course, you knew where they stood, but there were others. On the day when they arrested 93 of us, at five a.m. a man called me, a white man, and said, “I’ll be right over there, I want to get there before the police get there.” He came over and said, “Mr. Nixon, I’m sure they ain’t gonna let me get down there and make bond for you, and I don’t want you to stay in jail. Don’t let them take no picture of you behind the bars.” And he ran his hand in his pocket and pulled out 10 $100 bills.

Then right around six a.m., another white man called, a man who ran a business in a black neighborhood, and asked me if we had enough money to put up cash bonds. I said, “Well, I doubt that.” He said, “I’ll tell you what I’m gonna bring you: I’ll loan you $1,000.” And then he said so-andso is coming around to bring you $1,000. So we had $3,000.1 went to jail. And we got $11,000 altogether. I had money in my pockets. The bond was going to be $100, and I had enough money to make bond for everybody in the case.

We were arrested for violating the Alabama boycott law. That was in February. And every time they did something like that the people got stronger and stronger. We met twice a week, at different churches, and there was never a seat left.

It was a tough fight, it was really tough, and the bus boycott wasn’t by any means the only thing we did. But if I were a young man and had to do it all over, I’d do it again. Right now, I don’t mind telling you, I don’t know of anybody living that’s getting any more joy out of the work that he’s done and can look back on.

VIRGINIA DURR

In 1953, Cliff [Virginia’s husband] opened his law office, and I became his secretary. His nephew, Nesbitt Elmore, had been the first civil-rights lawyer in Montgomery; he had taken cases Mr. Nixon brought him. And he had just a terrible time. He was criticized. He had been a rising young lawyer, but when he took these civil-rights cases it absolutely ruined his practice. And then he went to Texas, but he had made a dent.

So Mr. Nixon began to bring these civil-rights cases to Cliff, and through Mr. Nixon we met Rosa Parks, who was a seamstress at that time at the Montgomery Fair Department Store. I always hate to tell the reason I got to know her so well, because it sounds like the lady bountiful, but it wasn’t that way at all. You see, I worked and I had three children. With three little daughters, it was always a question of taking up the hems or letting out the hems or taking the dresses in or letting them out, and when I worked all day in the office, I didn’t have time to do all that sewing. Mrs. Parks not only sewed all day at the Montgomery Fair, but then she also sewed at night and sewed on the weekends. So Mr. Nixon introduced me to her, and she began to do our sewing for me.

I soon became extremely devoted to her and realized what a remarkable woman she was. Mrs. Parks is really what you would call the perfect Southern lady. She’s extremely well-mannered, rather shy and timid. She had great devotion to her mother, who lived with her, and she had a husband who was sick a lot, so she really was supporting three people. She had gone to Miss White’s school here in Montgomery, where she was not only educated but learned to feel that she was just as good as anybody else, that she had the right to be an American citizen and to enjoy all the rights of citizenship.

The only thing she complained about very much were the buses. Mrs. Parks really resented the bus situation terribly, and Mr. Nixon did too. They had brought a number of cases, or tried to, on the whole bus situation. The first one I got interested in was the Claudette Calvin case. This was a young girl about 14. She was going to Booker T. Washington School and she was only 14, and her father was a ditch digger, I think, a day laborer, and her mother was a maid, and there was nothing in her background, as there was in Mrs. Parks’, that would make her think she had any rights at all. There on Dexter Avenue she was, sitting in the bus, and the driver called back, “Nigger, move back.” And she refused to move. They arrested her and took her to jail. So they decided to make a test case on Claudette Calvin, but the case fell apart.

The next one was Mrs. Parks’. People have said over and over and over again it was a planned thing. It wasn’t planned at all. Now Mrs. Parks had a great deal of feeling about the way people were treated on the bus, no doubt about that, and they had tried to get the cases going, but none of them succeeded.

Where she worked was a very hot place, with steam irons, and she was naturally tired, and then she had bursitis in her shoulder that night, and also she had several packages. So when she got on the bus, the Cleveland Avenue bus, which was largely black anyway, she sat down in the first available seat, which was in that indeterminate place in between the front and the back. There were two blacks sitting across the aisle and a black sitting by her, and then some white people got on the bus and the driver turned his head and yelled, “Niggers, move back!” She refused to move, so they came and arrested her. She never said anything; they just took her to jail.

Well, Cliff and I had come home from the office, and Mr. Nixon called and said that Fred Gray, who was then the lawyer for the NAACP, was out of town. Mr. Nixon had called down to the jail about Mrs. Parks, but they wouldn’t tell him anything.

Mr. Nixon came by and got Cliff, and I went with them. Mr. Nixon put the bond up for her because he owned property and we didn’t. And we all went over to her apartment, and she said she wanted to make a test case and take it all the way through. Cliff told her that he could probably get her off on a technicality, but she said she didn’t want to do that, she wanted to take it all the way through the courts and do away with segregation on the buses entirely.

She was arrested on December 1, a Thursday night. Then the trial was on Monday morning, and the courtroom was absolutely packed, you couldn’t get in it, and there was a tremendous crowd outside the court, too. That night they had the meeting at the Holt Street Baptist Church, and I tried to go, but you couldn’t get within blocks of it. Not only was the church absolutely packed but there were just thousands of people around the church. They had a loudspeaker so you could hear what was being said, but you couldn’t get in. That was the night that Dr. King made his famous speech, which as Mr. Nixon says, hung him to the stars. Really, it was absolutely marvelous, wonderful.

They decided that night that they would not ride the buses. So they walked for 381 days. It was the most amazing thing. You would see these old women walking back and forth, whether it was cold or hot or rainy. And you’d pick them up, and my friends and I would compare notes about it — they would all quickly say exactly the same thing. You’d see this big crowd walking toward Cloverdale every morning and walking back at night, and you’d stop and pick one of them up and say, “So you’re supporting the boycott?” “Oh, no ma’am, don’t have nothing to do with that boycott. The lady I work for, her little girl was sick this morning, so she couldn’t take me.” Nobody, never, would admit they were supporting the boycott.

We were living then at Mrs. Durr’s house, and her old cook, Mary, would rush down every day when we came home and ask us what was happening. She was terribly excited about the boycott. But when she was asked by the people in the house, my motherin- law and all, “Mary, are you supporting the boycott?” Mary would say, “No, ma’am, I don’t have nothing to do with the boycott, and none of my family has nothing to do with the boycott. We just walk, we just don’t have nothing to do with the boycott at all.” And later I said, “Mary, why in the world did you tell such a story as that?” And she said, “Well, when your hand’s in the lion’s mouth, the best thing to do is pat it on the head. Yeah, the best thing to do is pat it on the head.”

The thing that was so amazing is that it was supported almost 100 percent. I don’t think during that whole period of time I saw one black on the bus. I had a woman who came and washed and ironed for me, and I would go get her in the morning and take her back. The mayor said that the reason the blacks were winning was that the white women of Montgomery would take their maids back and forth. The police were on the watch, and if you drove 26 miles an hour in a 25 zone, you were immediately arrested. But the reaction of most of the women was so funny — they got all mad at the mayor and they said, “If the mayor wants to do my washing and ironing and cooking and cleaning and raise my children, let him come out here and do it. No, I’m not going to give her up.”

It’s not that these white women supported the boycott, and they didn’t think of it that way at all. They just thought they were getting their maids. And it wasn’t just that they didn’t want them to walk, either. If they lived a long way, walking would make them late in the morning. Of course, a lot of the maids did walk, the ones that had always ridden the bus. But the women who had cars had always gone and gotten them. I had always gone and gotten my washlady, and taken her home in the afternoon. She was a wonderful old lady. She belonged to a church called the Church of the Holiness of God, and she was a great admirer of Dr. King’s, and she said that she would see the angels spreading their wings when she went to one of his meetings, lighting on his shoulders and spreading their wings. And I think she really did see it.

They had a meeting every Monday night at different churches all over the city, and this was how they kept the people’s morale up. Oh my goodness, those meetings were absolutely remarkable, they were amazing.

It was a terrifically thrilling period. It was like seeing people come up out of the darkness and see the light. There was a feeling that the human spirit couldn’t be crushed no matter what you did to it — not utterly crushed. I wouldn’t have missed it for anything, and I’m always so sorry for the young people today who didn’t have the same opportunity, because I don’t think they’ve ever seen anything that exciting.

JOHNNY CARR

The civil-rights struggle grew out of the brave act of one woman. As has been said many times — a woman sat down and the world turned around. On that afternoon when she left work she did not know that her footsteps would lead to so great a movement. I am a firm believer that God used this incident and the leadership that was given by Dr. King to bring America and the world to a realization of the great injustices that the black and poor Americans were suffering.

Several organizations had worked very hard to get justice, but there seemed to be no justice for black citizens. They were denied first-class citizenship. They were denied decent jobs and housing and they could not vote. And the separate educational facilities were very unequal.

We look back in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s and we see a struggling people with leaders such as E.D. Nixon, who was looked upon as one who was not afraid to fight for his people, and Dr. S.S. Seay, and many others who supported the NAACP, the Montgomery Improvement Association, the Women’s Political Council and others. But it seems that in spite of all we did, we were never able to arouse the people to rally to a cause until 1955.

One of the problems black people had was denial of access to public accommodations. We did not have the privilege, for instance, of using the elevators in public buildings. The Bell Building was one. Every time I go to the Bell Building now and ride the elevator, I think about the day when they had separate elevators marked “colored.” Montgomery Fair, downtown, the big store that Rosa Parks worked in, had elevators that they refused to allow blacks to ride.

There were also, of course, the separate black and white water fountains. On the water fountains everywhere you went, if there were accommodations for blacks, there was a sign on them that said “colored.” It was impossible for a person to go to a restroom downtown unless you found a black cafe or establishment you could go to. You could go in their stores and spend all of your money, but you couldn’t use accommodations like these.

There were also stores that denied blacks the privilege of trying on certain garments in the stores. For instance, when a black person would go in to try on a hat, they would tell you you had to put a stocking cap on your head first. If you tried to establish an account at any of these stores, they would never call you “Mrs.” It would always be “Johnny Carr” or “Mary,” you know, just first and last names. Montgomery Fair was one that always did this. There were so many tilings that blacks suffered that at this point when you tell someone about it, it seems like a fairy tale, but it was true.

There was a human relations council. That was the only organization where blacks and whites were meeting together prior to 1955. They harassed those people. If they went to a meeting at night, the police would get their tag numbers and show up at their jobs the next day. It was hard for the whites who were involved, including the ministers. Any time you stood up and spoke out against something that was wrong for human beings, you were just branded.

This is what was happening in Montgomery and the South, and really all over the country.

When people say, “Look at the changes,” I always point out they were made because someone made them do it. It wasn’t that they all of a sudden decided one day these things are wrong, let’s get together and change these things. Someone had to suffer for it. And there has been a lot of suffering and a lot of blood shed to bring about even what we have today. Because when you went about doing what was needed to make things move, many other things happened.

Every stage of the periods we have gone through to get certain changes 20 At left: Rosa Parks sits in the front of a Montgomery bus on December 21, 1956, after a Supreme Court ruling banning segregation: at right: Rev. Martin Luther King, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Rev. Glenn Smiley and an unidentified woman ride a Montgomery bus soon after the Supreme Court ruling. has had its violence; people were killed and maimed fighting for their rights. And it had to go all the way to the courts before finally being resolved. And that only happened because the suffering people were going through down here made folks in other parts of the country sit up and protest. Right now it doesn’t appear there is as much going on because you don’t see as many visible protests. But there is a smoldering underneath.

Of course it was a long, hard struggle before the buses were integrated. Blacks were always able to ride on public transit in Montgomery — buses, streetcars, whatever. But they always had to take the back seats or stand if all the blacks’ seats were filled.

On the bus that came into the black community, the South Jackson bus, blacks could have almost all the seats on that bus except for the seats just behind the driver. Even if the bus was filled up, you didn’t sit in those very front seats until the bus passed St. Margaret’s Hospital, which meant you were out of the white community. Then the driver would turn around and say, “You all can sit up here.” The average indignant person would just keep standing.

All of the drivers were white until after 1956. Some of them were kind, but some of them were so nasty. They would take the money at the front door, then you had to go around to the back door if you were black to get in. But if the bus was crowded and you didn’t hurry up and squeeze in there, he’d take off and leave you.

There was a young woman named Claudette Calvin. This was before the boycott. She refused to get up off her seat on the bus one day and was arrested. She went to court and was fined, but we were not able to get the movement behind her. There were several incidents like that. The Montgomery Civic League and the NAACP would call meetings and organize support, but it never grew into anything. That’s why I always used the phrase that the man and the hour met. Dr. King was here when Mrs. Parks’ case came up, and he was selected to be the leader at that time.

There really wasn’t a decision as such to focus on the buses instead of other issues. When the first meeting was called, the idea was to stay off the buses one day to show our resentment about how Mrs. Parks was treated. And when they had the first mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church, the thing really started to blossom into what it became. If the city fathers had just given one inch it might not have.

All we were asking at first was that blacks be able to take available seats from the back to the front, with whites seated from front to back, and we were just going to stay off one day. It wasn’t the plan of the people all that much. But things started moving and Dr. King was the type of leader he was, plus the people he had with him like Reverend Hubbard and others. The response of the people was so strong in these mass meetings, they would think maybe we need to keep moving forward.

They didn’t dream people would stay off the buses 381 days. But they did. There was one point where they took all the buses off the street because they weren’t making any money.

After the protest was over they asked them to hire black bus drivers. But the city said, “No. If we hired black bus drivers, blood would run in the streets like water.”

So then we took it up with the bus company officials in Chicago. They sent their representatives down here and talked to the people. They told us to find competent bus drivers and they would hire them. Then they went into the city fathers, who said they would pull out their franchise if blacks were hired.

The man met with us at nine the next morning and said the company had okayed the hiring of black drivers. And he added, “One thing we want you to understand — we don’t have any black routes or white routes. A bus driver drives any route. But we’re going to hire black bus drivers and if the city fathers say they are going to take the franchise, they’ll just have to prove it. The only thing we want to know is — are you all ready to suffer whatever consequences may occur when we start using these drivers?” Every person there said we were ready.

We did have some incidents where whites shot at a bus, things like this. I don’t think any drivers were physically attacked or injured, but they were insulted. Sometimes a white would start to get on the bus and see it was a black driver and get back off. But there was never as much white clientele as black anyway.

During the boycott, we formed car pools. At that time they said we were breaking the law if we formed car pools. This was a station right here. People used to be at my house at 6:30 in the morning to ride to work. We had met at churches for rides, but they broke that up. So then we started meeting at houses. My car is my car and I can ride anybody I want to in it. Sometimes I had to get seven or eight people to work in the morning and then we had to get to work ourselves.

The mayor said as soon as the first rainy day came, all the blacks would be back on the buses and glad to get back on. The first day it rained it was a sight to see — people just walking in the rain, water just dripping off of them, soaked but they just kept walking. And it poured that day, and all of us who had cars drove all over town picking them up.

Every time the mayor or one of them said something it just reinforced the Movement and helped us to be more forceful in what we were trying to do. Some of the white businessmen said if the mayor would just keep his mouth shut, it would have ended because every time he opened his mouth, he seemed to put his foot in it.

After 381 days, the buses were completely integrated. Dr. King and Dr. Abernathy were the first persons who rode the bus after the boycott. They got on and just rode the bus all around, sitting right up front.

Dr. King always took a realistic view of what you should be doing as you gained and what the other man would be thinking as he lost what he thought he had. He would illustrate it at the meetings, saying, “If you had something and someone took it away from you, what would your attitude be?” All that was part of the nonviolent attitude. He said not to be ugly or anything but polite when we got on the bus.

The boycott put Dr. King in a position of leadership, and it gave people the courage to stand up and fight for other things. After the buses we had a project to integrate the lunchrooms, the library [blacks were not allowed in the main downtown library] and the city parks. Oak Park [the only municipal park at the time] was closed down, and they closed the swimming pool down too and never did open that back up. Now, 25 years since the boycott, we can point with pride to many accomplishments. We have fair housing laws, we have better jobs, we can go to any public place, we can vote but won’t. We have elected officials and representatives on many of the boards of the community. And we can attend the school or university or college of our choice.

Yet we realize that we have not overcome all of the obstacles in our lives. When we see hate in the eyes of our fellow man, when we see the racist organizations coming back all over the country, we know that there is much left to do. We have come a long way, but have a long way to go.

Rosa Parks: Interview by Cynthia Stokes Brown

Cynthia Stokes Brown grew up in Madisonville, Kentucky, and now teaches and writes in Berkeley, California. This article is part of a longer piece based on recent interviews with Septima Clark, Virginia Durr and Rosa Parks. She thanks them for telling their story and also thanks Marge Frantz, Myles Horton, Herb Kohl, Sue Thrasher and Alice Walker for helping her understand it.

“Find out just what people will submit to, and you have found out the exact amount of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them; and these will continue until they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress. ” — Frederick Douglass, August 4, 1857

In December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks resisted with neither blows nor words, but with a simple act of noncompliance. Most accounts of the Montgomery Bus Boycott would have us conclude that she acted suddenly and spontaneously, for no other reason than that her feet hurt. No planning, no reflection, no relationship with other people lay behind her act — she was just a tired black woman. But we would not only be very wrong, we would also be seriously slighting Rosa Parks, for she had been thoughtfully resisting injustice for years.

Forty-two years old when she refused to give up her seat on the bus, Mrs. Parks (born Rosa McCauley) had lived in or near Montgomery since childhood. Her father was a carpenter, her mother a teacher; early on, the family had moved from Tuskegee to a little farm near Montgomery, where the girl often stayed awake nights fearfully awaiting the arrival of the Ku Klux Klan, though it never appeared.

Her mother was a woman who had been mistreated badly but had the courage to stand her ground against trouble. Mrs. Parks recently recalled one of those times: “Years ago there was an item that a collector was going to take from her. In fact, it was a coat that was not quite paid for. My stepfather bought it, and he owed $2. The man was coming to take the coat. But she told him, ‘You are not going to take this off my back, I know.’ And he didn’t do it. She was often telling people what they wouldn’t do, those who be oppressors. Instead of saying, ‘Yes, sir,’ she was always saying, ‘No, you won’t do this’ or ‘You won’t do that.’”

Rosa McCauley attended Miss White’s School and then Alabama State College, and a few weeks before her twentieth birthday, she married Raymond Parks. He was a barber, and when she first met him in 1931, he was helping raise money to save the Scottsboro Boys from the electric chair. In the early 1940s, Mrs. Parks joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, serving as secretary and working with young people. Most young people, though, were discouraged by their parents and teachers, who told them they had better leave the NAACP alone, they had better not disturb the “good race relations” in Montgomery if they wanted to get along in life.

How could race relations have been considered “good?” Mrs. Parks explains, “Everything possible that was done by way of brutality and oppression was kept ’ well under the cover and not brought out in the open or any publicity presented. Occasionally — in Mississippi, for instance, with the murder of Emmett Till — people talked about how awful it was, when at the very same time the same act was committed against a young minister whom my husband knew very well. With the exception of him and this young man’s mother and the men who threw him off the bridge into the river, no one knew. She was not supposed to complain. There were several cases of people that I knew personally who met the end of their lives in this manner and other manners of brutality without even a ripple being made publicly by it. So we knew this.”

The bus was the place where black people were rudely and routinely reminded of where they stood with white society. Mrs. Parks tells of one incident that her mother endured on a bus: “She sat down near the back of the bus in a seat with a young white serviceman, and he became so incensed because she dared take this seat that he threatened to throw her off the bus. She stood up very politely, smiled in his face, and said, ‘You won’t do that.’ I was hardly able to contain myself. But before I could say anything, there came a very deep bass voice of a brother in the back of the bus. I don’t know who he was or what he looked like, but he said very clearly, very distinctly, ‘If he touches her, I’m hanging my knife in his throat.’ So he didn’t touch her, and I was happy he didn’t, because he would have been pretty badly hurt by me with what I had, only my fingers.”

Rosa Parks worked as a seamstress at Montgomery Fair Department Store, altering the clothes bought by white customers. Despite her work with the NAACP, she says she did not feel courageous at all. By her account, she felt tense, nervous and upset most of the time. “All of the suffering and all of the struggling and the effort that we put forth just to be human beings sometimes seemed a little too much.” She believed that she was not going to benefit personally, that she had been destroyed too long ago. But she was willing to face whatever came in the hope that the young people would benefit.

Then in the summer of 1955, she got the chance for a break and a change. Myles Horton, the director of the Highlander Folk School, wanted someone from Montgomery to come up to Highlander, and he asked two of his good friends there — E.D. Nixon and Virginia Durr — whom to invite. They agreed that the person who should go was Rosa Parks, who badly needed rest and support.

Mrs. Parks had never before experienced interracial living. But for two weeks in Tennessee she ate with white people and slept in the same dormitories with them. Highlander had been defying the segregation laws of Tennessee since the early ’40s to provide a place where blacks and whites could meet together.

At Highlander Mrs. Parks met two people who came to mean a great deal to her. One was Myles Horton, who, she says, “just washed away and melted a lot of my hostility and feeling of prejudice against the white Southerner because he had such a wonderful sense of humor. I often thought about many things he said and how he could strip the white segregationists of their hardcore attitudes and how he could confuse them, and I found myself laughing when I hadn’t been able to laugh in a long time.”

She continues, “People were trying to make it seem impossible to have that type of living that he had organized at Highlander. There was a great thing about black and white people sitting down to the same table eating. Now the black person could stand up and hand them the food at the table and have a meal. But the two were never supposed to sit together and have a meal. But lie managed it, and these reporters were asking him, ‘How do you get the two races to eat together?’ And he says, ‘First, the food is prepared. Second, it’s put on the table. Third, we ring the bell.’ I find myself just cracking up many times.”

Mrs. Parks also met Septima Clark, then serving as the school’s director of education, a woman whom she soon admired for her ability to organize and hold things together in the informal setting there. And Mrs. Parks says she quickly came to hope that some of Clark’s great courage and dignity and wisdom would rub off on her.

In the meetings, though, Clark says she found Rosa Parks to be so nervous that she would not tell about her work with the NAACP in Montgomery, which had included getting the Freedom Train to make a stop there. But one evening in the dormitory everybody started singing and dancing, white and black women together, and they asked, “Rosa, tell us how in the world you got that Freedom Train to come to Montgomery.” This is how Clark remembers it:

“Mrs. Parks said, ‘It wasn’t an easy task. They wouldn’t let the Freedom Train come unless the white and black children went in together. So they did, and that was a real victory for us.’ But she said, ‘After that I began getting obscene phone calls from people because I was president of the youth group. That’s why Mrs. Durr wanted me to come up here and see what I could do when I went back home with this same group.’

“The next day in the workshop I said, ‘Rosa, tell these people how you got that Freedom Train to Montgomery.’ She hated to tell it. She thought that certainly somebody would go back and tell white people. But she got up and told that group about it.

“At the end of the workshop we always say, ‘What do you plan to do back home?’ Mrs. Parks said she planned to work with those kids and to tell them that they had the right to belong to the NAACP, they had the right to do things like going through the Freedom Train.

“Rosa had not planned at Highlander that she was going to refuse to get up out of her seat. That evidently came to her that day. But many people at the Highlander workshop told about the discrimination on the buses. I guess practically every family around Montgomery had had trouble with people getting on buses. They’d had a hard time. They had a number of cases where bus drivers had beaten 15-year-olds who sat up in the front or refused to get up from their seat and give it to whites coming in. That was the kind of thing they had, and they had taken it long enough.

Tags

Tom Gardner

Tom Gardner is a writer and photographer who has covered movements for change in the South since 1964. He is now a staff writer for the Montgomery Advertiser. (1981)