This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 2, "Long Journey Home: Folklife in the South." Find more from that issue here.

This is Nat D. on the jamboree and I’m down here to tell you something about how WDIA got kicked off, started rolling and started everyone to jumping, and I’ve been jumping ever since. So now you listen to me, I’m gonna give you a little history lesson.

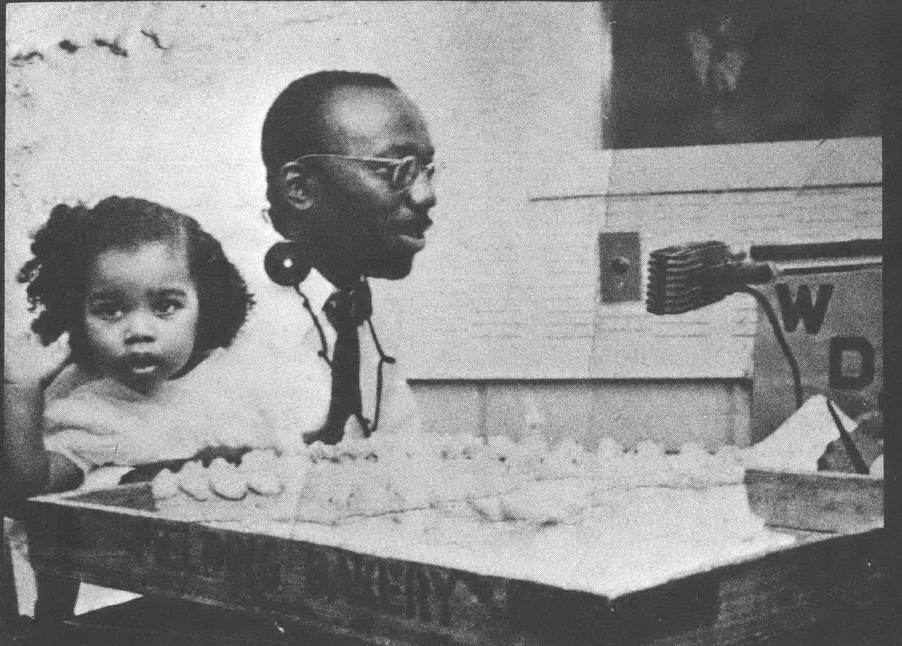

Nat D. Williams, known in Memphis as “the Granddaddy of black jocks,” sat sipping his coke on his porch swing, eyeing us through his enormously thick glasses and occasionally letting loose with one of his famous laughs. While his grandchildren peeked through the screens at us young white folks and our machines, Nat D. took turns lighting pipes, cigars and cigarettes — and skillfully weaving stories about his beginnings on radio.

As you twirl across your radio dial today, it is incredible to think that only 40 years ago black programming was revolutionary. In the 1930s and ’40s, playing black music on radio was a new, often bitterly contested practice. Once it began, it grew rapidly, not as a result of altruism, but in response to the changing economic conditions of the South, as businessman Max Moore explains:

The Interstate Grocer Company was organized February 13, 1913. Mr. E.P. Moore, an uncle of mine, and Mr. W.W. Moore, my father, organized the company. Back in those days, the biggest operation that we had was from the farming angle. The large farmers had their own commissary and did their own furnishing to their sharecroppers. Naturally, they were interested in buying as cheap a merchandise as they could to furnish them with - for instance, flour and meal. That went on for many years before the chain stores moved into the small towns.

It begin to change up when the farmers begin to get rid of their day -labor. Tractors and combines began to take the place of the old mule-drawn machinery. Therefore the labor begin to move away from the farms. Then the folks had a chance at buying a little better grade offood, particularly flour and meal. That was when we got interested in establishing our label. We come up with King Biscuit Flour.

After we got the flour and begin the distribution on it, we had the idea that it would be a good plan to do a little advertising behind it to get it moving. And that was when we thought about the radio.

Interstate Grocer Company’s radio program, “King Biscuit Time,” was first aired in 1941 on the Helena, Arkansas, station KFFA. The show featured the live blues of harpist Sonny Boy Williamson (also known as Rice Miller or Sonny Boy Williamson II) and his band. The response from the black community, who had never heard blues on the radio, was overwhelming. Sales of King Biscuit Flour increased so much that Max Moore decided to introduce a new brand of com meal. He called it Sonny Boy’s Com Meal.

Although Sonny Boy died in 1965, the show — as well as the flour and meal — continue to be popular in the Delta region around Helena. “King Biscuit Time” still features Sonny Boy’s recordings in a program format which now includes pop, soul, rhythm & blues and rock ’n roll.

The success of “King Biscuit Time” quelled the advertisers’ and station owners’ fears that “Negro radio” would cause a white backlash. Although KFFA did receive threats, they were far outnumbered by positive responses - and the resultant increase in revenue.

In Memphis, Bert Ferguson was closely watching the growing success of “King Biscuit Time.” His station, WDIA, followed the country-and-westem format common throughout the region’s radio; but in the intense competition for a limited number of advertisers interested in reaching the predominately white C&W audience, he found his station failing. At that point, in 1948, he made a decision best left to Nat’s description:

Mr. Bert Ferguson, who was out there at WDIA, had worked with me at “Amateur Night on Beale Street. ” He had heard of me down there on the Palace stage jumping and hollering and going on, so he thought perhaps I’d be useful on the radio. I think the big idea was that there wasn’t enough people coming in to get those ads and things. He figured, well, now I’ll do something that nobody else had done and maybe that’ll attract somebody. So he decided to venture up with Negroes. I was the first Negro that he worked with, and he figured that I ought to be representative of all of them. Since he offered to pay me, I thought I’d be useful, too. They paid $15 a week. That was big money then. He told me to come out to the radio station. He would put me on my first program.

Well, he didn’t put me out on the program soon as I got there; they gave me a whole week to practice. And I practiced, but I didn’t have any blues records to play. I didn’t have anything but records by white artists. We didn’t have any Negro blues, feeling like they get down to you in your bed when you felt down low. So they told me to take some of those white artists and play them. And I never will forget the first one I played was an affair called “Stompin’ at the Savoy. ” Well, “Stompin’ at the Savoy” was all right, but it was a little too fast for me. Of course when I told them that I’d rather have some blues, they played some and listened. They said, “We can’t put this on the air. ”

I said, “Why?”

He said, “It might be censored or against the law. ” There wasn’t anything all that wrong about the blues from my point of view. It was just a case where they thought it wouldn’t be so polite to give it to a general audience of people consisting of all kinds of people, black, white, red and green, so to speak.

My first radio program was a very, very serious situation. I had practiced for about two weeks getting ready to say what I was going to say when the man pointed his finger at me to start talking. And, of course, that day came. And when he pointed his finger at me, I forgot everything I was supposed to say. So I just started laughing cause I was laughing my way away. And the man said, “The people seem to like that; make it standard. Keep laughing, Nat. ”

And I’ve been laughing ever since. (Laughter.) Well, that’s the way I started.

Have you ever noticed that for a typical black man, in the South particularly, the first cover-up he takes is to laugh. And when he laughs that covers up a multitude of sins. And so I laid on out and laughed. I laughed for two reasons. First, I was covering up the fact that I had forgotten, and next I laughed because I realized that I had done lost the job and wasn’t gonna get that new suit I wanted. But the man told me to come back tomorrow. I went back the next day and he says, “Start your program laughing. ”

I said, “Start laughing about what?”

“Man, start your program laughing. ”

Ever since then, except on Sunday when I’m doing the religious programs, I start off laughing. Laughing became a trademark for me, and it still is. W

hen the radio stations began to present more black programs, they had to stop and think about what kind they ’re going to do. Of course, Mr. Ferguson and the others who were the managers of the stations didn’t know that there was a chasm between what they had been hearing and what appealed to Negroes. They didn’t know who to get for these programs. So I began to look around the town to see what I could get. My biggest handicap was finding Negro talent that was suitable to put on the air at that time. Most of our programs were earthy. We got on down there where the guy lived, and we talked about things that interested people. Say, “Come here baby, tell me where you stayed last night, your hair’s all nappy and your clothes ain’t fittin’you right, tell me, where you been honey?” And she would go ahead and tell him. Well, that was the kind of singing we was doing. We sang about things like that.

A former high school teacher himself, Nat D. returned to the Memphis high schools in his search for prospective radio talent. It was in the schools that he found Maurice “Hot Rod” Hubbard and A.C. “Moohah” Williams, who still works for WDIA.

Later recruiting efforts were better organized. In the early 1950s, WDIA staged a “D.J. Derby,” which gave blacks of all ages and backgrounds a chance to try their hand at radio. The men who came in first, Robert Thomas, and second, Jesse “Hot Rod” Carter, recount their experiences:

Robert Thomas: I used to love radio. As a matter of fact, when I was growing up as a youngster, I listened to all the radio stations around town, and tried to pattern myself as a jock. There were some I had as my favorites and I used to practice with a mop stick, a broom handle, anything like that. I’m holding a microphone up in front of me and I’m rapping. But really it was a fantasy with me because I didn’t think it would come to be. But it did, it came about. And as it came about, I found myself being what I had originally thought I wanted to be in the first place.

I had gone off to school. I went to college. Forgot all about radio. Started to thinking that I wanted to become a dentist. And when I came home for the break once from school, my mother informed me that she had heard an announcement on WDIA that they were going to have something they called a Disc Jockey Derby, a type of a contest where you come out and audition.

There were 300 of us that came out, male and female. About 48 passed the audition test. A series of programs were to follow with each auditioner having 15 minutes of air time on A.C. “Moohah” Williams’ show. A.C. had a Saturday show in the afternoon from about four until seven, or till sundown (the station was just a daytime station then). It was called “The Saturday Night Fish Fry,” and around five o ’clock was when he would begin the auditioners’ portion. Each auditioner had a 15 minute segment. He would do his commercial spot and cue the control man when he wanted his next record. All he had to do was concentrate on how he would do his spot and go into a record, or how he would make the transition from a record to a commercial and go out of it. Everything was supposed to be connected to flow. And this was primarily what I had to concentrate on.

During the course of the audition, which was over about a four-week span, we had the preliminaries, the quarterfinals, the semifinals and the finals. And at the end of the finals, I was number one. I remember with me in that D.J. Derby was one of my cohorts who worked at KFFA in Helena, Arkansas; calls himself “Hot Rod” Carter. He came out number two.

Jesse Carter: The way I got involved in radio was purely accident. I never had no intention of getting into radio. It didn’t interest me at all. One Sunday morning my wife and I were tuning around for “Wings Over Jordan, ” a religious program on WROX in Clarksdale, Mississippi. The time had passed and we got instead a sanctified church. I heard the piano playing and I told my wife, “That sounds like my cousin, Johnny Strong. ” I said, “What do you know? My old cousin’s on the air.” I said, “One of these days I’m going to get on the air. ” Just like that. Just like you say, “Oh, I’m going to buy a new car next year, ” or something like that.

I didn’t think no more about it. I got into the cafe business. Let out a lot of stuff on credit and the fellas ran me down so low til I decided to shut the door. When I closed up I owed one salesman $28 for cigarettes. I talked to him, I said, “If you got any work to do over there, I’ll come over and work it out.” He says okay. I worked that $28 out driving a truck route on the Mississippi side. Whenever I didn’t work I’d go on back home and turn my radio on. Once I heard an announcement come in over WDIA that anybody who wanted to learn to be an announcer, be up there that Saturday and they would give you a test. And if you passed the exam why they’d give you four months free coaching. I said, “Well, I’ll take that. ” Just like that and that’s just the way it happened.

It was kinda cold that first day I went up. I had to hitchhike, I didn’t have no money. At the station there were only two other fellas there as old as I were. The rest of them was youngsters, all dressed up sharp. I was there with common things on and that old Mississippi mud all over me. I said, “Shucks, I shoulda stayed at home. I know I don’t have a chance. ”

Well, for the evening we was supposed to take our initial test. Mr. David James, the program director, had told everybody to be here at five o’clock. He said, “If you’re not here forget it. The first rule in radio is don’t be late. ”

I had to hitchhike that day, too. I caught a series of three rides from here to Memphis, starting out with a little woman over there in Mississippi, friend of mine. And I decided once not to go. She said, “Oh yeah, you go ahead. ” So I went on and I got in the studio about 15 minutes ahead of time. They thought I wasn’t going to make it. When I sat down to the mike, we just had about two minutes, I guess, before we go on the air actually. Since all of them had little stage names, he asked me, “Whatcha gonna call yourself? Watcha gonna call yourself?”

I say, “I don’t know. ”

Said, “Call yourself “Hot Rod. ”

“Okay, this is old Hot Rod. ” So they started to call me Hot Rod and it just stuck. Out of 46 contestants only three was picked. And I was one of the three. That’s right. And after about five months, I came down here and got a job.

Hot Rod, at 68, still works a Sunday shift on KFFA where Robert Thomas, too, was first employed doing King Biscuit Time, among other shows. Within a few months, however, Thomas was hired away by WDIA to do a youth-oriented program — and it has remained his specialty ever since. Of course, black teenagers aren’t into the same music as they were back when WDIA first started playing the blues. Today, as Robert Thomas notes, disco dominates the scene:

These teenagers got to not be into blues, you know. You start playing the blues and the youngsters would call up and ask when would you play some music? Youngsters couldn’t relate to blues, and I think mainly the reason is because they were more music-minded. Blues was just simple. They just used a guitar, which wasn’t popular then with youngsters as it has become now. You had a guitar and a big bass drum. Most of the blues singers weren’t polished musicians. We’d play the top things then for youth appeal like the Eldorados, the Spaniels, the young groups that were coming out at the time. They called it rhythm and blues.

Now youngsters going to school, they’re being taught music as it is. Then they’re able to put it together and listen to others, how they put it together, then they can relate to it more. So that’s what they’re doing. There was a time when the kids just dance to the beat. But the kids have become more sophisticated now; they listen to what the vocalists are saying now. They don’t listen if you just got a beat and there’s no story there. Now you got to have both of them, both of those ingredients.

We watch the national charts pretty closely, and if it is doing that well across the country, we figure we ’re missing the boat if we don’t play it. So we play it. There was a time we didn’t play any white music at all, regardless of how great the record was. But like I said, the sophistication of the kids is going onward and upward, and the black kids, as well as the white kids, are buying white records. The trend is moving in that direction. It’s semi-jazz.

Now we don’t call our music jazz music for fear that some of our great blues listeners might tune out, you know, because they don’t like jazz. They’ve heard one jazz tune and they didn’t like it, so now they don’t want to hear any other parts of jazz. But we are able to play this new type of music and it seeps into them and before they know it, they’re snapping their fingers, patting their feet, you know, bumping up against the refrigerator listening to it unknowingly, and enjoying it, and at the same time it’s jazz. So we call it disco. This is where the trend has been for, oh, the past couple of years now. So we hopped on the bandwagon and, by virtue of that, we are able to play a lot of jazz now, without calling it jazz.

The Southern black’s economic plight has continued to change. The change in radio and music are symptomatic, and in many ways symbolic, of greater changes within black culture. One thing all change has in common is that it isn’t free: something must be paid, something must be exchanged. Nat D. can’t help but view this situation with mixed emotion.

There are other changes too. Have you ever noticed the change in referring to people like myself? We don’t use the word Negro too much now. We say black. I don’t know why a change was made, but we said black radio, not Negro radio. It’s acceptable to me because I am black. On the other hand, I don’t think it should be used to play anybody down. I think it was just a useful change and I, more or less, like it.

Have you noticed a definite change though? I have noticed it. What I mean by change; when you turn on a black program, the people don’t use black approaches. They don’t use black situations. Black’s turning white now. Whether that’s a desirable development or not, personally I don’t know. I don’t think so because I like to be what I am. I’m not mad about being black. I just figured the other cat is losing a whole lot of things when he doesn’t accept me as a human being like himself. And the result is a lotta laughs that I get, he misses. He ain ’t tickled as I am, and I’m tickled because I think he’s ridiculous in many respects.

Changes is coming about so fast now til I’m beginning to get a little worried again like I was at first. Negroes are not Negroes like they used to be. We using better English, and wearing better clothes, and we living in different areas, and we traveling. And the result is we are changing personalities, so to speak. We not the same people that we used to be and as we change whether we turn out to be something better or worse, I don’t know.

Right now I’m saying that personally I’m doing all right. I’ve been having my meals regular. I been sleeping pretty good. I had some pretty good laughs. And who else, who can beat that? You can tell me somebody can beat good meals, good laughs, good feeling, you point him out to me; so I want to know how they did it. I’m gonna put it just like I used to say on Beale Street: I ain’t mad about nothing, man, I ain’t mad about nothing. So, what’s you mad about pretty baby, you better get up, set up, and grin. You hear. Am I talkin ’ too fast?

Tags

Mark Newman

Filmmaker Bill Couturie is an associate producer with Korty Film of Mill Valley, California. Mark Newman is a graduate student in American history at UCLA. This article is based on the research they did while producing the film King Biscuit Time for the US Information Agency. (1977)

Bill Couturie

Filmmaker Bill Couturie is an associate producer with Korty Film of Mill Valley, California. Mark Newman is a graduate student in American history at UCLA. This article is based on the research they did while producing the film King Biscuit Time for the US Information Agency. (1977)