This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 1, "Behind Closed Doors." Find more from that issue here.

Politics in New Orleans has always been fascinating because the game is played with such cynicism. New Orleans politics is trickster politics; ideology means nothing, rhetoric is a tool of the poseur. It is only natural that the person on the bottom — the black who is barely surviving in this society — is the most cynical of all toward the electoral system.

Certainly blacks know that electoral politics, even in the last decade with the elections of Moon Landrieu, Edwin Edwards and Dutch Morial, has not been their road to power and independence as a people. In the American political system, independence stems from economic power — politicians don’t represent the “people,” they represent the economic interests that elect them; these interests in return expect protection and the services of the system. Economic power is exactly what the black community of New Orleans does not have, so in the end black politicians either represent white interests or opt for rhetoric, which, however sincere, is usually impotent.

Black Atlanta, on the other hand, has for several decades been a strong economic community, reaping the consequent political benefits. In fact, in Atlanta the power interests of black and white money often coincide. Atlanta is middle-class America, and the blacks there seem very satisfied to emulate the whites. Not only an emulation in style of acquisition, but in values, lifestyles, even speech. This is the real reason why Atlanta is “the city too busy to hate.” They are busy making money.

What they do with the money is something else, but suffice it to say that middle-class black Atlanta would never pause during the good day’s work to join a parade. Nor is the thought considered anything but New Orleans foolishness and if not immoral, certainly recidivist. Black Atlanta ties into a system of middle-class respectability fully supported by the big churches and the six colleges. Their suppression of black culture or any lifestyle that white America cannot identify with is typified by an attitude toward the power structure of “we’re just like you,” and in its more highly developed stages, “we’re more like you than you if you knew the best in you.” In this system, black Atlantans look upon African heritage like some long-suppressed family illegitimacy. Even the down-and-outs who wander up and down old Hunter Street (now the new Martin Luther King Boulevard) wear suits and ties, the better to pick up a free drink.

Compared to Atlanta, New Orleans is a breath of fresh air — but if air cost money, a lot of homefolks would suffocate. The food is great, but it is becoming more expensive; the music is great, but one cannot eat music. If New Orleans had a large black middle class, possibly their interests and the interests of the white power structure would coincide as in Atlanta, but I doubt it. As it is, the policies of the New Orleans white power structure seem to be designed to keep the black community underfoot while giving up nothing, making no concessions, not even to the twentieth century.

Dr. James R. Bobo, a University of New Orleans economist who has watched the direction of the New Orleans economy with alarm, noted in his exhaustive and well-publicized 1975 study, The New Orleans Economy: Pro Bono Publico, “we really have two economies and two societies, one conventional and one unconventional (the underworld of economics). The most distinguishing characteristics of the underworld economy are: 1) incredibly high unemployment, 2) abject poverty and poorness, 3) relatively low educational attainments, 4) the degradation of welfare for many, 5) human, social and physical blight and 6) substandard housing.”

Bobo gives documentary support to what struggling blacks here see all the time: the expensive renovated uptown houses in contrast to the prisonlike Desire Housing Project downtown, the buses primarily ridden by blacks, the tourist trade at the expensive New Orleans restaurants seen only when the kitchen door swings open, Parish Prison, Central Lockup and the criminal courtrooms filled daily with blacks. Black youths wash the dishes, sweep the floors, cook the fast foods, polish the image of New Orleans glamour. And a lot of these jobs are work-this-week-off-next-week.

In 1969, 38.2 percent of New Orleans’ black families lived below the poverty level, as compared to only 25.2 percent in Atlanta, 26.8 percent in Houston and 26.5 percent in Dallas. Since then, the relative position of New Orleans has probably worsened. Bobo concludes that “. . . low labor force participation rates, economic discrimination, the relatively low educational preparation of the labor force because of the disadvantages of poverty and being poor, with its attendant high rates of unemployment, underemployment and unemployability, have contributed to our relative impoverishment, a condition of impoverishment greater in degree than for all major metropolitan areas, Atlanta, Dallas, or Houston, or for that matter, the entire nation.”

The overwhelming thrust of Bobo’s criticisms has to do with fundamental New Orleans economic weaknesses, and the longstanding failure of the power structure to recognize them, and to recognize with the exception of the police force increases, that the entire city suffers from the consequences of the condition of its black poor.

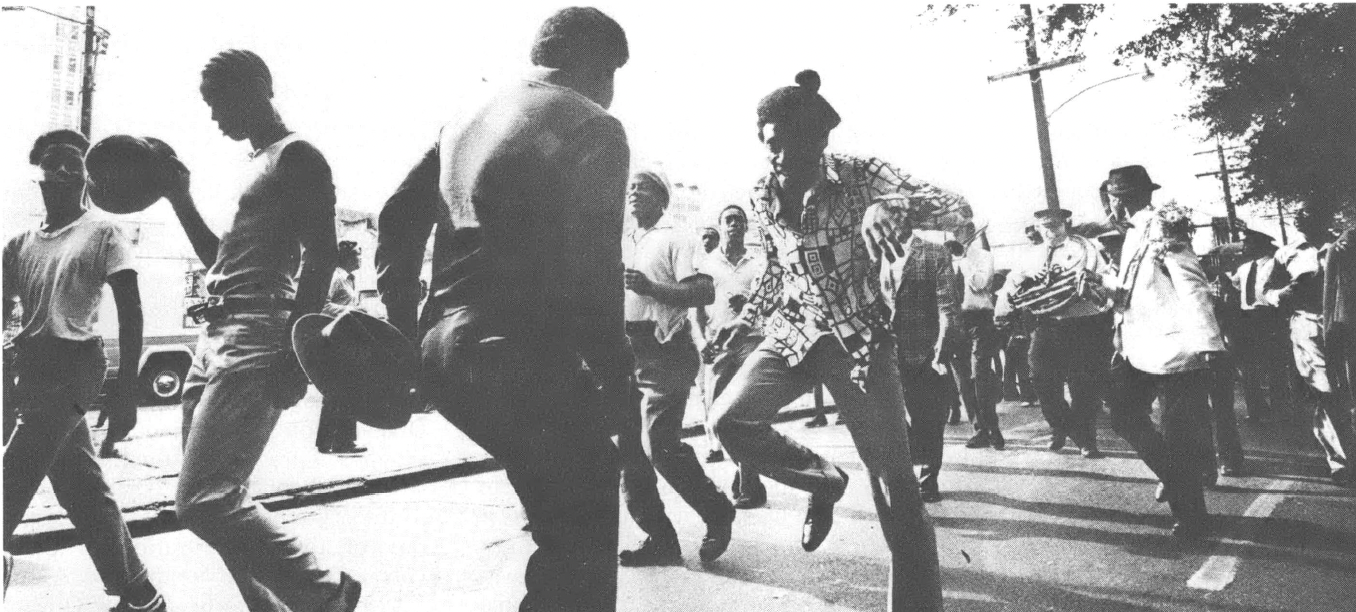

Economic inequities are not the only distinctions between blacks and whites in New Orleans. We must begin to view the descendants of freedmen as a people who inherit not only the horrible legacy of slavery, but the strong positive legacy of African cultural retentions, especially in music, dress, the various racial societies, dance, cooking, parades, funerals, and the joy of something we might call the theater of the street. (To some extent these qualities exist in all large black communities of the South, but they are ever more so in New Orleans.) The gaiety, the love of life that whites (and many blacks) perceive on the faces of blacks here, particularly during cultural celebrations, is often misinterpreted as a sort of mindless contentedness, as if the people had not the sense (or the cause) to be angry.

It is my feeling, however, that this attitude toward life is a cultural strength that makes it possible for people to survive the hard times despite their frustrations — though white New Orleans, especially some of the younger enthusiasts of black music and culture, usually sees black culture as devoid of political and community consciousness in the same way their elders thought the beatific look on the faces of black musicians was due to their own “tolerance,” the kindness and indulgence of the ruling class. Culture, music, parades, funerals — all of it — as it operates among black people in New Orleans never eschews political or economic considerations, however much these aspects may be suppressed. On the contrary, culture can be the very instrument that best conveys the political and economic interests of the people, though it has not been generally viewed this way.

The appeal of culture is why so many blacks remain in New Orleans, or return, seemingly against all economic reason. “It’s a good town,” many a black New Orleanian will tell you even away from the city. “Can’t make no money but no other place like it.” Then they will talk about the good times: the music, red beans and rice, the parties, gumbo and what happened at carnival, or the mystery and intractable perversity of the place, the rains, the family histories of entangled bloodlines, then the music again.

All this means that full black political strength in New Orleans must begin to include people with lifestyles and interests at odds with middle-class America: the second-liners, the people who walk the unemployment lines, the people who were born in and have never left the projects, the welfare mothers and the welfare children, the people who wash dishes in the famous Quarter restaurants, the people who live in rundown New Orleans housing — the people to whom the vote now means nothing. They have been the cynical ones, and for good reasons. Most of the nonparticipants, the non-voters, feel that politics is “white folks’ business.”

Will politics ever become “black folks’ business?” If so, what will make it so? Black New Orleans culture is at odds with mainstream American culture, a historical reality not only not likely to change, but in my opinion, not desirable of change. The extreme poverty, the raging unemployment in hard-core black New Orleans, makes it almost impossible for the community to elect representatives who will further its interests in traditional political ways. Once the black community elects someone, it is difficult to hold that representative faithful after she or he is exposed to the lure of greater amounts of money from competing mainstream economic interests, whether in plain ole dollar payoffs or jobs which offer huge increases in salary. ‘Opportunity’ for newly elected black politicians, themselves poor, appears in shiny traps wrapped in red ribbon.

In addition there are the problems created by the skillful direction of the potential black vote through outrageously gerrymandered districts — or brilliantly gerrymandered depending on how you look at it. Although the Supreme Court recently ruled that the present at-large, five district representative structure of the City Council is constitutional, it does not shake the conviction of most blacks that both the councilmanic and state legislative districts are now and have always been drawn with the aim of diluting black voting strength. Black voting blocs have also been discouraged by the racial housing pattern of New Orleans: in the old city, since the abolition of slavery, blacks have lived in just about every neighborhood. It is said this pattern developed because so many blacks worked as servants and the whites wanted them to live nearby; in the same way, in the French Quarter, slaves lived in the rear of the houses of their white owners.

The potential black vote is even further defused by the traditional practice of buying off neighborhood organizations for — well, if not pennies, for rent money. During the last decade, SOUL (the Southern Organization for United Leadership) attempted to put a stop to this, but what has happened to SOUL is a case of history repeating itself. SOUL grew out of the concentration of black voters in the lower Ninth Ward. As the first really strong black New Orleans political organization in the twentieth century, SOUL was, for a time, a solid step forward, built largely on the small black homeowners and middle and low-middle-income blacks who populate the area below the Industrial Canal, a commercial waterway that runs between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. The Lower Ninth Ward represents mostly post-World War 11 growth, offering an opportunity for black home ownership not possible in the inner neighborhoods of New Orleans, and the lifestyle of a small town as satellite of a great city. SOUL also reached across the Canal to organize the area around the Desire project. (The area Tennessee Williams wrote about in A Streetcar Named Desire — part of the area was then Polish — is also the area where whites were most active in resisting the beginnings of school desegregation in the early 1960s.) Desire, however, is much more poverty-stricken and politically impotent than the Lower Ninth.

In a sense, SOUL was a child of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), the civil rights organization that attempted to organize New Orleans in the early ’60s. It was also a product of the extremely active ’60s legal firm of Nils Douglas, Lolis Elie and Robert Collins (now the first black federal judge in the South), CORE’S local legal defense firm and the meeting place for New Orleans veterans of the civil rights movement. Nils Douglas was the first to test the political waters in the Lower Ninth in 1966 with workers buttressed by Movement veterans. Douglas lost this election, but within a few years he put together a formidable organization which controlled the ward’s state representative office and became a power to be reckoned with in all city political affairs. Meanwhile, Douglas’ law partner, Robert Collins, created COUP (the Committee for Organizational Politics) in his native Seventh Ward (primarily creole blacks). COUP often endorsed candidates in tandem with SOUL.

By 1970, when Moon Landrieu ran for Mayor and Edwin Edwards for Governor, SOUL-COUP had such a strong position it could guarantee the delivery of at least 80 percent of the city’s black vote. Landrieu won the mayorship almost entirely because of the black vote, receiving less than 30 percent of the white vote. Edwards, after a messy primary, won a close gubernatorial race because of the solid bloc of black supporters delivered by SOUL-COUP and other black groups in New Orleans.

As a result of Landrieu’s mayoral victory in 1970, SOUL struck some deals that most people feel were beneficial to the New Orleans black community. It is generally believed that in return for their support, Landrieu agreed to black control of federal community action and model cities programs; in addition many blacks gained prominent city jobs including, near the end of Landrieu’s term, Chief Administrative Officer Terrence Duvernay.

Certainly the Landrieu-SOUL marriage was an extremely beneficial one for both parties and through it the very face of City Hall, previously so hostilely white, seemingly stocked by straw-hatted, cigar-smoking Irish or Italian bosses, blackened before our very eyes, blackened in ways whites who liked the way things were before Landrieu could not accept. On the other hand, it should never be forgotten that it was a bargain; during his crucial eight years Landrieu was able to win almost every key election he had a stake in because of his dependable bloc of black support — of which a large part, but certainly not all, was orchestrated by SOUL-COUP.

After such notable successes, the quick demise of SOUL (COUP still exists as a fairly potent force) is difficult to explain. In a sense it can be explained by saying the leaders followed the classic pattern: lacking a strong economic base, they took whatever jobs—from judgeships to independent business opportunities-became available during the Landrieu years, and used the political organization to protect their new-found economic opportunities. Early in the game, severe splits emerged within SOUL over direction, between the rank-and-file and the leaders, between those from Desire on one side, and those from the Lower Ninth and Gentilly on the other; the inclination of the leaders to further their own interests at the expense of the rank-and- file did not inspire unity.

In addition, leader Nils Douglas, though a fine strategist and conceptual thinker, never seemed able to articulate SOUL policy in a way that could transcend the labyrinthine organizational endorsements. Finally Douglas, always a rather phlegmatic politician, left the leadership role, and with his departure went what remained of organizational cohesion. By the time Landrieu’s term was ending in 1978, SOUL had split into factions and was fighting itself in the courts, a sad spectacle indeed.

Ironically and possibly tragically, it was during a period of setbacks for black political organizations in New Orleans that Ernest M. Morial was elected the first black Mayor in 1977. Morial possesses a distinguished record as a civil rights attorney and is a protege of the late A. P. Turead, the pre-eminent black civil rights attorney in Louisiana during the legal battles against segregation. Morial is also a product of black New Orleans’ strong creole legacy, a people who have historically suffered from confusions and indecision about racial identity, often preferring, even when self-professedly black, to see themselves as a third group between the whites and the dark-skinned African retention blacks of Congo Square heritage. Culturally, the creoles of color of earlier generations looked to France, not Africa (or America) as the paradigm of civilization.

Morial has always identified black, but his career has eschewed alliances with black political organizations, he has always seemed to move in splendid isolation. Nevertheless, he became the first black state representative in the late ’60s and soon after narrowly missed a bid for City Councilman-at- Large.

When Morial announced for Mayor to succeed Moon Landrieu he was considered by most blacks to have no chance. What happened was almost unbelievable. Morial ran an excellent campaign in the first primary, coming out strong as a ‘black’ candidate, identifying his aspirations with such as Tom Bradley of Los Angeles and Maynard Jackson of Atlanta. It soon became obvious that Morial would be one of five candidates to be taken seriously, and it accrued to his advantage that he was the only black in the race.

In the first primary, Morial carried almost 90 percent of the black electorate, to the dismay of three of the white candidates who had reputations as racial moderates and hoped for at least a part of the black vote. Morial has always had his enemies among blacks in politics here, but he in fact received an almost unanimous endorsement from the black electorate without begging for it or having it delivered to him by an ongoing organization; it was, as some said, “a secret black bloc.” Therefore, totally unexpectedly, Morial ran first in a closely fought five-man primary, and very importantly, the three white moderates split their vote, throwing the one rather conservative white, Councilman Joseph DiRosa, into the runoff against Morial.

After a few debates and an aggressive and sometimes bitter campaign in which Morial gave no quarter, it became obvious to the power structure he was the only choice; one who would be able to hold, if not actually improve on, some of the ‘progress’ gained during the Landrieu administration.

Yet Morial’s election means almost nothing to the blacks on the bottom rung, those who have never been involved in the political process. As if to underscore the meaninglessness of any substantial gains for the black community, upon winning Morial has steadfastly maintained he is not and will not be a ‘black’ Mayor, owing nothing particularly to the black community. Such rhetoric is hardly necessary, since the black community has no method of calling in debts. In a sense, Morial, in contrast to Maynard Jackson of Atlanta, presents the spectacle of a ‘black’ Mayor whose prime distinction is that he does not act like a black man.

If there is to be any meaningful change in New Orleans, we may have to arrive at a politics not of profit or extraordinary power, but of survival. The person who puts together this new black political structure might be the person who, after winning, does not take a better job, does not move ‘up’ as the fruit of political labors. We are not talking about a new, more radical ideology (however desirable this may be), but a new breed of community political activist, one who does not identify as a political ‘professional,’ one who has the luxury of not needing to convert political efforts into immediate cash reward, jobs or contracts, who has no desire to be the object of political glamour or to acquire a judgeship or appointive post. Hopefully, this person will work for years on the building of black organizational coalitions and their skillful use. Until one day the sight of a plum becomes too sweet. .. . A

ll this may sound dreamy, but if it ever happens it will probably happen this way. The only real political salvation for the black community in New Orleans is self-help, the building of strong coalitions, and the retaining of dedicated people at the level where they have to answer primarily to the interests of the community — not the power structure.

Meanwhile, when it comes to politics these days it’s all Atlanta. Black New Orleans has a big corner to turn. But when it turns it won’t be the same corner as Atlanta, which is the same corner the rest of America always turns, it will be its own. Then, as one prominent black Southern politician — a native of New Orleans who left to go elsewhere — said, his eyes opening wide as he comprehended the idea of political leverage plus culture, “then you would have a monster! "

Tags

Tom Dent

Tom Dent, a native of New Orleans, has worked with the Free Southern Theater and the Congo Square Writers Union in New Orleans. He has published a number of poems and essays, and is currently working on a book of essays on the black South since the Civil Rights Movement. (1979)