This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 3 No. 4, "Facing South." Find more from that issue here.

The last decade has seen a new era begin for the southern textile industry. For years it has been haunted by its low profitability and poor public image. At last, industry executives are determined to shake those features and take steps toward putting on a “new face." For the first time in over a century of operation, southern textiles may develop into a modern, capital-intensive industry. But the pace of the process and the extent of its success are complicated by a morass of labor stirrings, capital shortages, entrepreneurial caution and governmental interference.

The change taking place is a momentous one, comparable perhaps to that caused when the textile industry crossed the ocean from England to New England, and again when it left New England (and the workers who had begun to demand higher wages) and headed south a century ago. This new period, however, is not marked by a geographic move, but by simultaneous forces demanding changes of all aspects of the industry, and by the determined responses of textile executives.

In the last few years, for instance, the industry has witnessed a significant shift in the composition of its workforce. Mills no longer operate as white-only reserves. In fact, low income blacks now account for more than 20 percent of the textile workforce. They have brought with them independent attitudes and strong feelings of support for the union. For an industry which has intimidated workers and fought unions with more success than any in the country, this can only signal trouble.

At the same time, the federal government has recently established restrictive federal pollution, safety and health regulations. And though the government has rarely pushed for compliance, new organizations of retired and active textile workers have arisen, demanding that companies abide by the laws and clean their plants of such health dangers as excessive cotton dust in the air.

In response to these worker-related problems, the textile industry would like nothing more than simply to eliminate their workers through automation. The technology finally exists to fulfill at least some of these management hopes, and companies have begun to lay-off workers and replace them with new machines.

Until recently, textile companies have been unable to afford automation, for they have stayed small compared to most major American corporations. For the past seven years, the federal government has even banned mergers, encouraging companies to remain small. Now that ban has been lifted, and the large companies will soon begin to buy up smaller ones, to gain the capital necessary to automate even more.

These changes will totally reshape the industry and the lives of its hundreds of thousands of workers. This new era, however, has not yet fully arrived, and the industry is now in a period of transition, still as affected by its unique past as by its future. To understand the industry today, and the forces shaping its future, one must look to the lives of those who have worked in southern textile mills (see accompanying articles) and to the economic and social realities that form the industry's background. Among those realities:

• The majority of US textile mills are located in an arc across the South, extending from northeastern North Carolina, through the piedmont to the textile "capital" of Greenville, S.C. (60 percent of the textile workforce is said to live within 100 miles of that city), down to Georgia and into the black belt of Alabama. Within this arc can be found 656,000 workers in thousands of textile mills.

• Textiles has been, and remains, the dominating force of the southern economy. Its $16-18 billion of sales annually is 30-50 percent larger than the volume of southern agriculture. In five southern states it employs over 25 percent of the labor force, despite growing automation.

• When textile owners began operations, many located their mills in small towns or wilderness areas. They made their towns dependent on the mill economy. Often the mill was the only employer, rented all the homes, owned the stores and shops. The company alone made up the local power structure. Without it, the town would have died.

• Since its first years, low income whites have traditionally filled the southern textile workforce, and whole families have frequently been employed at a single mill. Women have always been a major portion of the workforce, and even in 1974, 47 percent of textile workers were women, compared to 29 percent in all manufacturing industries.

• No industry has avoided unionization as successfully as textiles, primarily by settling in the South. Twenty years ago, the industry included 252,000 union members. Nationally, there are now 141,000 members among the 800,000 workers. Less than ten percent of the southern workers are unionized.

• Textile workers' wages once compared well with national industrial averages. In 1950, textile workers earned $1.13 per hour, while the industrial average was $1.09. By 1955, however, the textile average wage had slipped a penny below the national average and since then it has plummeted even more. In 1975 the average textile wage was only 61 percent of the national average, $1.30 less.

• The industry has been extremely vulnerable to spurts and cycles. Production and marketing continue to be archaic and unpredictable, and profitability is always uncertain. When one company hits on a hot-selling consumer item, others jump into the "marketplace," crank out a similar product and inevitably glut the market, sending the industry into another tailspin. These cycles of oversupply occur every three or four years.

•Well-connected northern investors have historically shunned southern textiles. Its cycles have been too irregular, its profit margin too small, its selling operations too haphazard. An investment in textiles has always been a gamble, and investors have avoided it for more lucrative industries.

• Given the little amount of capital required to begin a new mill, the competitive nature of the industry and the government's ban on mergers, no companies have dominated the field. The industry's two giants, Burlington Industries and J.P. Stevens, have been able to corner less than ten percent of the textile market, while the rest is scattered amidst 4,000 small firms, almost three-fourths of which are still family owned.

•Without money from investors, textile companies have been unable to afford the few high-priced pieces of automation that have been developed. And with a steady supply of cheap labor they have had no need to.

For years these were the steady background forces of the southern textile industry. They became basic truths, unchallengeable. Now their firmness is crumbling, and with their fall, a new era is being entered.

Blacks Revitalize Workforce

No part of the industry is in more flux than the workforce. Many long-time textile workers have chosen to leave the mills on their own. The late 1960s brought about a new round of industrialization for the South. During this period, many electronics, metal fabrication, heavy equipment and chemical manufacturers moved into the region, often fleeing the unions and higher northern wages. These new industries have taken white workers out of their traditional mill jobs and moved them into higher paying job categories. As the textile industry's pool of unskilled whites has dried up and is lured away, it has been forced to look toward a group that it had systematically excluded-poor southern blacks.

For many years, blacks had been used as an effective threat in keeping mill workers' wages at low levels. Whenever there was discontent among the white mill hands, the owners could play on the whites' racial fears with the threat that blacks would take over their jobs. At long last, this exclusionary policy has been ended and blacks are no longer used as an outside threat, but are inside the mills, at work.

Many plants that were once all white now include workforces that are more than half black. Throughout the industry, 20 percent of the workers are black. These workers, offsprings of the civil rights movement, are unlike their patemalized white predecessors. They do not blindly follow all the rules that their bosses have established. Employers have complained of “discipline" problems, increased costs of employee training programs and a higher turnover. According to R.P. Timmerman, president of the Graniteville Mills in South Carolina, the number of blacks in his mills “is reaching a level where you begin to have problems."

The most distressing “problem" to the mill owner is the black workers' sympathetic attitudes toward unionization. Already young black textile workers have played leading roles in union victories at the Oneita Mills in Andrews, S.C., and at J.P. Stevens' seven-mill complex in Roanoke Rapids, N.C. Employers have responded to this activity with threats, rumors and accusations. During the organizing campaign at the J.P. Stevens plants, the supervisors circulated pictures of the San Francisco “zebra" murder victims and the black suspects in the case. The pictures were captioned, “Would you want this to happen here?" Mill owners have also equated the advent of unionism with a black takeover of the workplace. In a letter to its employees at one plant, 80 percent of whom were white, Stevens executives wrote: “A special word to our black employees. It has come repeatedly to our attention that it is among you that the union supporters are making their most intensive drive— that you are being insistently told that the union is the wave of the future for you especially—and that by going into the union in mass, you can dominate it and control it in this plant, and in these Roanoke Rapids plants, as you may see it."

These tactics have allowed mill owners to continue intimidating the white workers, but have not stopped the flow of blacks into the mills. The numbers of black textile workers continue to rise, along with their interest in unionization.

The Union Returns

As white workers have known for decades, black workers are learning the problems of building a strong union. Although organizing efforts have been made since the 1880s, only eight percent of the textile workforce is unionized. For the Textile Workers Union of America (AFL-CIO), every day is another struggle to stay alive; which, in turn, has demanded more organizing. And organizing has become increasingly difficult.

During the 1950s, the union lost most of its membership base when the textile industry increased its flight to the low-wage, non-union South. Many of the union's northern locals were eliminated, depleting its financial resources and making the cost of new organizing too expensive. Impoverished, the TWUA has been forced to depend on the Industrial Union Department, the organizing arm of the national AFL-CIO, which under the leadership of George Meany and I.W. Abel has been less than enthusiastic in carrying out its mandate to "organize the unorganized."

Organizing in textiles has always been a dangerous business, yielding mainly pyrrhic victories and numbing defeats. During the past 13 years, the TWUA has concentrated its efforts on the industry's second largest chain, J.P. Stevens. With the exception of a union election victory among 3,000 workers in J.P. Stevens' Roanoke Rapids plants, the drive has been largely unsuccessful. In Roanoke Rapids, Stevens executives responded to the union victory with a vicious anti-union campaign: union supporters have been fired en masse, organizers have had their phones tapped and its supervisors have tried to spread rumors of black takeovers, higher crime rates and inter-racial marriages. Workers are warned that the company closed down its only other plant, in Statesboro, Ga., where the union had won bargaining rights.

Primary to the industry's anti-union strategy is the firing of union supporters during the organizing campaign. For example, in the Stevens campaign, the company illegally fired 289 workers, and eventually had to reinstate them and award back pay of over $1.3 million. In addition, the National Labor Relations Board has found Stevens guilty in 13 separate "unfair labor practices'' cases, none of which has been overturned by the courts. Despite such fines and law violations, Stevens continues to believe it's cheaper to fire union supporters than give in to their demands. For the union, this strategy has effectively squelched most organizing efforts. With each new organizing drive, the company steps up its anti-union efforts, filling other workers with fear, while the union's main adherents have been effectively eliminated. Months or years later, the slow wheels of the NLRB may turn, fining textile companies and possibly reinstating the fired union supporters. But the damage has been done, and the NLRB can only give too little, too late.

Still, the union has been a continual aggravation for the industry. And since winning negotiation rights at Stevens' Roanoke Rapids plants in August, 1974, the union has posed the threat of staging a major comeback.

Dirty Work

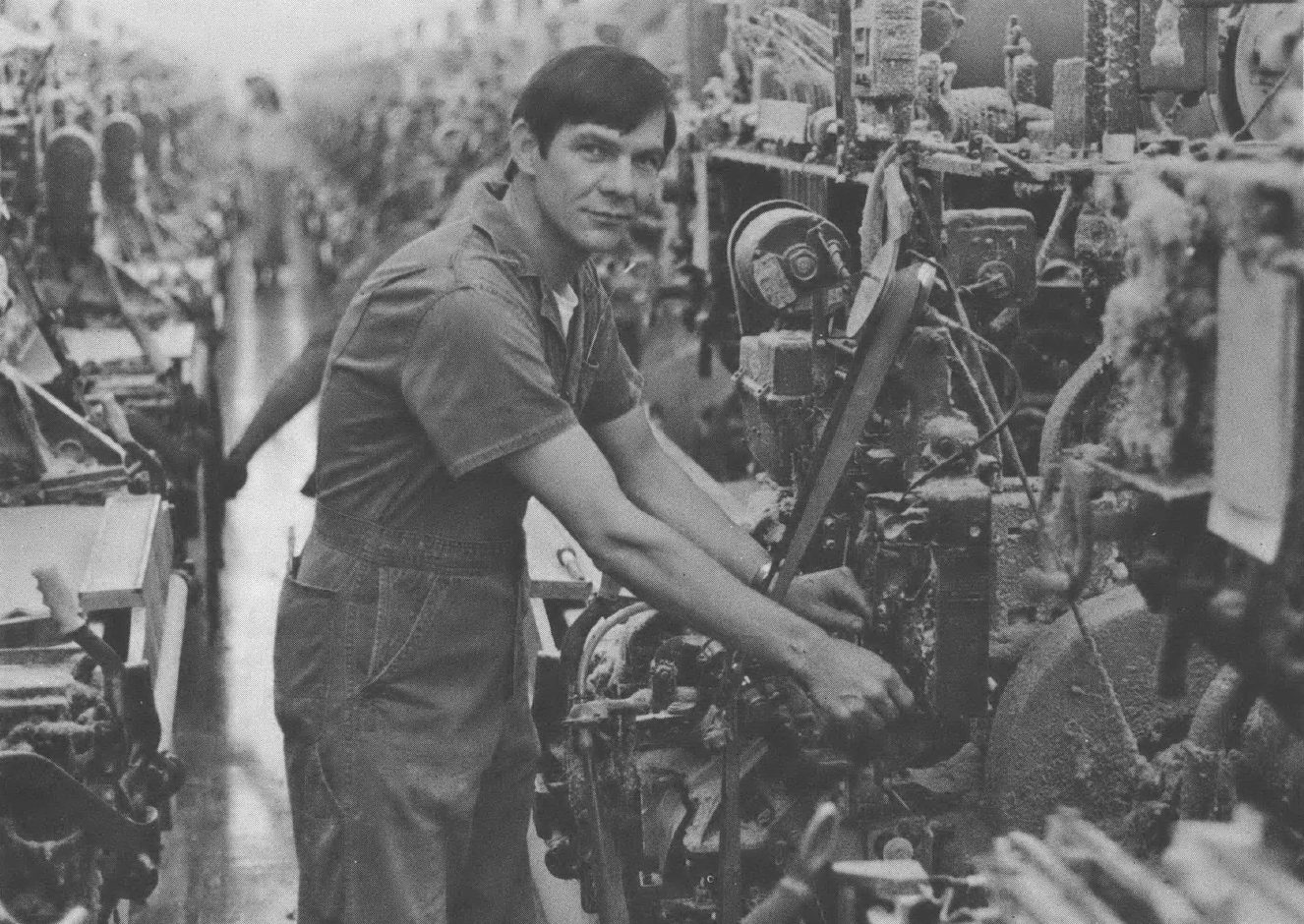

Industry executives have fought unions for years, but now they have to face a new challenge: the government and workers who are not necessarily allied with the union. For many years, the industry has hidden behind the excuse of low profits, pleading its inability to clean up either the working conditions in the mills or the pollution they produce. With its new plans for automation, the textile managers hope to eliminate many of the dangerous and unhealthy working conditions by ridding themselves of the workers entirely. In the interim, though, most textile workers continue to labor amidst numerous toxic substances, deafening noise levels, unsafe machinery and deadly, disabling cotton dust. According to figures from the US Department of Labor, as many as 100,000 textile workers are now suffering from the chronic lung disease byssinosis, caused by excessive exposure to cotton dust. Medical researchers have also estimated that as much as 25 percent of the textile workforce has been deafened by the noisy looms.

During the past year, a new organization, the Carolina Brown Lung Association, has been formed for the expressed purpose of fighting for better conditions for mill hands, as well as for just compensation for those whose health has already been destroyed. In North and South Carolina, the Association is pressuring the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to carry out a vigorous enforcement policy against mills that violate the OSHA cotton dust standard. Thus far, the governmental agencies have been unwilling to move against the powerful textile interests.

Instead of undertaking the costly process of correcting the dangerous conditions, the textile industry has responded to these initiatives with a torrent of rhetoric attacking the “imposition of unreasonable government regulations." F. Sadler Love, secretary-treasurer of the American Textile Manufacturers Institute claims that the proposed government regulations on noise, cotton dust and waste-water quality would cost the industry $3.5 billion over a five year period. According to Love, “This would amount to more than all the profits of all the textile companies in all the states of the union and would result in soaring textile prices to the consumer, no wage increases for employees, no dividends for stockholders and no modernization of plants or machinery." The American Textiles Reporter, a trade magazine, remarked about the explosiveness of the situation: "It remains to be seen whether OSHA will be as big a bane to the industry as were the flying squads of union organizers in the 1930s." Already, the industry has begun warding off campaigns for better working conditions with almost as much venom as it once directed against those flying squads.

Endangered Species

Dissatisfied (and even militant) black workers, a potentially aggressive union, worker and government pressure about pollution, safety and health regulations —these forces have worried southern textile mill owners recently. Now they have found a simple way to overcome them: replace the workers with machines. During the 1960s, the industry saw a boom in the development of textile technology, particularly in Czechoslovakia and eastern Europe. New machinery was developed which will revamp nearly every step in the textile production process, combining several operations, increasing machine speeds and decreasing the need for labor. Chute-fed carding machines, open-end spinning and shuttle-less looms are expected to increase substantially cloth production, while drastically cutting the need for labor.

Burlington Industires has already begun its automation. According to Horace Jones, the company's chairman, operating floor space has been reduced by 13 percent during the past year and the number of Burlington employees has been slashed by 17,000 from its peak of 88,000 in October, 1973. Despite these cutbacks, the company has maintained its annual productive capacity of approximately $2.5 billion, and spent over $100 million on new equipment during 1975. In the coming year, the company's capital spending is expected to reach $175 million, almost all of which will go toward modernizing plants and equipment. According to Luther Hodges, Jr., chairman of North Carolina National Bank, these trends may spread throughout the industry: "Burlington has rehired fewer workers than it was forced to lay off when the recession began. Other companies are following the same pattern and it could be a long, long time before the southern textile industry employs the number of people it did before the recession." Bureau of Labor Statistics figures show that employment in the southern textile industry dropped by 107,200 jobs during 1975 alone and more cutbacks are expected.

Even more jobs will be lost and automation increased in the wake of a recent government action ending its 1968 ban on mergers within the textile industry. Textile analysts have said that a major reason for the merger ban was the government's desire to protect the South's large unskilled labor pool. For years the industry has provided low-wage employment for this large bloc of the South's workforce, offering them some employment but discouraging them from developing other skills. The government was apparently afraid that if the industry giants were given free reign to carry out mergers and increase monopolization, then the process of replacing low-skilled workers with machines would also be quickened, and the South would be left with a much larger pool of unemployed, low-skilled laborers than before. It passed the merger ban and the industry remained bloated with small, highly-competitive and unprofitable companies. With the end of the merger ban, this will soon change. Burlington and J.P. Stevens and the other large companies (see accompanying box) can be expected to grow. Many of the smaller ones will be swallowed. Companies will merge, operations will consolidate and thousands of jobs will be eliminated.

These are the forces at work within the southern textile industry. Essentially they make up twin movements: the workforce is becoming less docile and more willing to complain when treated poorly by the industry. The executives have responded with actions that provide more reasons for complaint.

A new era is beginning for textiles, but it is still too early to determine the exact growth moves of the industry. Even with mergers, the industry may not find the capital sufficient to automate to the extent that the new technology makes possible. And the workers may take for themselves the power necessary to halt both the approaching automation and the continuing slump in their wages compared to those in other industries. Industry executives may find new tactics that will succeed in placating the militant new textile workers, or those workers may trigger an organizing movement within the mill that has never before been achieved. Whatever the final results, one thing is clear: it's a new day for the southern textiles industry.

Tags

Chip Hughes

Chip Hughes, a former Southern Exposure editor, is on the staff of the Workers Defense League and coordinates the East Coast Farmworker Support Network. (1983)

Chip Hughes, the special editor for this issue of Southern Exposure is an organizer with the Carolina Brown Lung Association. (1978)

Chip Hughes, a member of the Southern Exposure editorial staff, and Len Stanley have worked extensively on occupational health issues including organizing with victims of brown lung disease in North Carolina. (1976)