This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

In the following profile of Dr. G. Arly Brown and the people he serves, the names of the patients have been changed to safeguard their privacy.

“Some of this is pathetic, but you’ve got to laugh a little bit or you’ll go buggy,” says G. Arly Brown, MD, as the office door closes, ending another “session” with the Garcia family.

The Garcias are sick. Mentally ill. Living, as Brown says, in “total chaos.” Mother, father and sixteen-year- old son are suffering from schizophrenia and an unusual blend of mental disorders that have caused “people who supposedly know what to do to throw up their hands.”

Every month or so the Garcias of Duval County, Texas, climb into the family car, drive fifteen miles to Freer and visit with the doctor. They squeeze into the small office at the mental health clinic, where Mrs. Garcia politely takes charge. Her husband and son stare at the walls and mumble only when spoken to.

Mrs. Garcia tells Brown about life without Valium and sleep, life overrun with CB radios and police scanners. She talks about how the boy spends most of every night listening to all the lawmen and “good buddies” and watching the scanner’s little red lights blink. She tells of sleepless nights filled with blinking lights, noise and the fear of inflated electric bills, how the boy sleeps until eleven a.m., and how she goes across the street to the restaurant and buys him breakfast “because he won’t eat what I fix.”

For Arly Brown, specialist in family medicine, these weekly get-togethers at the mental health clinic require only a few hours of time, but demand special efforts from a man who “makes no pretense about being a psychiatrist.”

It’s just part of the job. When you are the provider of medical care for much of two counties out back in south Texas, you see and hear plenty; and the call to action often comes with unusual twists.

In fifteen years of mending bodies in the heart of Duval County, Brown has seen poverty as widespread as the south Texas scrub brush, and knows how talk of hygiene and nutrition can wipe an expression off a patient’s face. He has learned about leprosy, tuberculosis and the bureaucrats at HEW.

“I remember the federal government sending an inspector down here to look over the hospital. Well, when she got to the kitchen she just raised hell about our food service, and she told me to fire the dishwasher because she didn’t have a high school diploma,” Brown says with a seasoned snicker.

“Now here you had a woman supporting three kids on that little bit of money she was making, and here was some government inspector from who-knows- where who could care less about Freer, Texas, telling me to fire her. I told the woman no way.

“To show you how much that woman had on the ball ... I asked her to send us material, written in both Spanish and English, about diet and preparing nutritious food in the home. And about two or three weeks later I got a package in the mail from Washington, and all that was in it was a booklet, yes sir, in English and Spanish, for preparing squid in its own ink.”

“Something Had To Give”

At 44, Arly Brown is as much social worker as he is doctor. A majority of his patients suffer from diet and/or hygiene deficiencies. They lack healthrelated education and, as a consequence, an understanding of preventive medicine, and many live without the means to pay for even basic medical care.

Tuberculosis, diabetes and dysentery are more prevalent in Brown’s patient area than in most regions of the country. He deals with a high instance of iron deficiency anemia, obesity, hypertension and other dietary complications. And, as in most rural areas where people spend a lot of time outdoors, the doctor treats numerous accident victims. Like others who deliver medical care in rural areas, where health professionals must do without medical centers, sophisticated equipment and the support of colleagues, Brown says, “You do the best with what you’ve got.”

“When you come into the brush, it’s like moving onto another planet. You just don’t have the programs, facilities and services available. You don’t have the resources and support you have in metropolitan areas,” he explains.

Brown came to Freer in 1963 to set up a partnership with Dr. Lynn Tooke, a friend from medical school. A year earlier, Tooke had reintroduced the medical profession to the small town at the request of residents concerned about the loss of their two doctors.

Tooke spent a year trying to convince Brown they could both make a living in the area, and after twelve dissatisfying months in Beaumont, Texas, he gave in and came to Freer, a move Brown says he doesn’t regret.

The two set up shop in the town’s old wooden-frame hospital, stocked with such sophisticated equipment as a hot plate for sterilizing surgical instruments. Over the next four years, they bought new equipment and worked to upgrade medical care in Duval County, an effort that bore fruit in 1967 with the opening of a personally financed, thirty-two-bed hospital.

Three years later, however, Tooke and his wife died in a fire, and Brown was left with a two-person practice and the responsibilities of a busy hospital.

A hospital with such ancillary services as laboratory, pharmacy and x-ray is a golden nugget of medical care that many rural areas ana most towns of 3,000 people don’t have. In 1976 the people of Freer and the surrounding area learned again to do without when Brown, exhausted, was forced to close the hospital. Now, as before, area residents seek hospital and specialized medical care elsewhere, in places like Alice, thirty-five miles away, and Corpus Christi, eighty miles away.

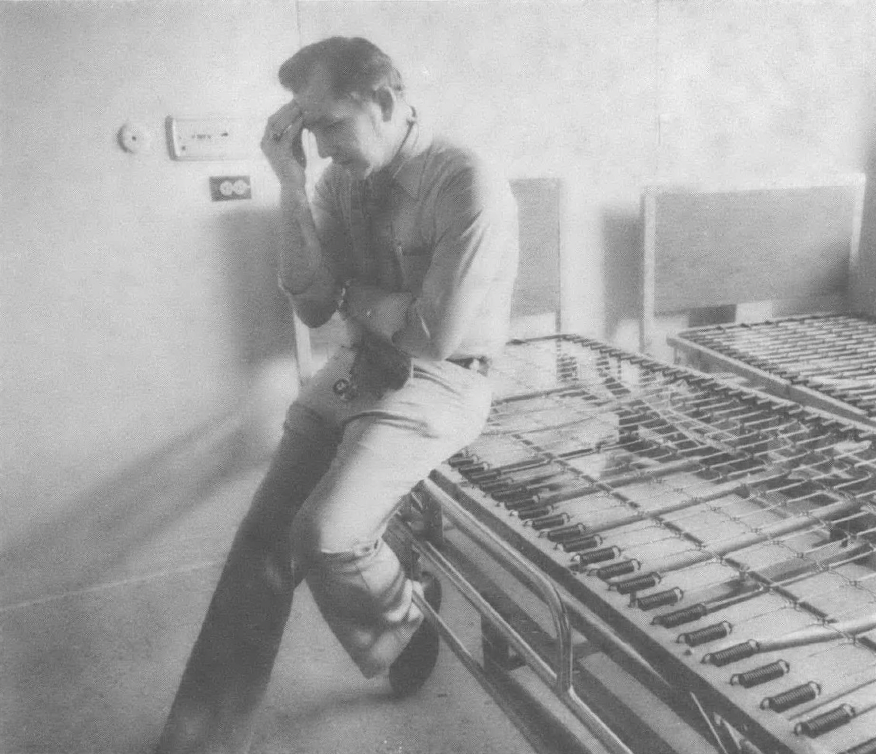

“It was more than any man could handle. I went from Easter until November [1976] with only one day off, and not being able to leave, always having that responsibility hanging over my head, was getting me down physically and mentally. I was staying up two and three nights in a row, until finally it became unbearable and something had to give,” Brown recalled.

Now the sole provider of health care in two counties, Brown serves an average of 200 patients a week, confronting the problems peculiar to rural medicine and facing the unexpected sides of life as a small-town doctor. He is still looking for a partner and a way to reopen the hospital. On call twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, he serves a predominantly Mexican- American population with a below-average standard of living. It is a situation not unusual for south Texas.

Consider the area surrounding Duval County, called the Magic Valley — a lush tourist haven where palm trees grow and restaurants and visitors from Dallas and Monterrey gather in exclusive shops on both sides of the border.

Here the Rio Grande River winds its way through silt-rich fields; trucks loaded with the Valley’s harvest make their way north past the giant ranches and oil fields of south Texas. This southernmost region of Texas boasts beaches, palm trees, orange groves, cattle ranches and oil. And in the midst of it all, poverty and poor health are rooted and thriving like Johnson grass.

“The lush, semi-tropical beauty of the area often obscures its severe health, education and development problems,” notes a study by the Lower Rio Grande Development Council. The area depends on agriculture. Unemployment is high and the population is 73 percent minority — Mexican-American. The Magic Valley is the core poverty area in the south Texas Triangle, that predominantly rural, often remote region stretching from Corpus Christi to Laredo to Brownsville. The Triangle boasts the lowest rural and metropolitan per capita incomes in the nation.

With economic, cultural and environmental factors stacked against them, the poor of south Texas are caught in a vicious cycle — being poor often means being sick and being sick means staying poor. Study after study points to the pressing needs of the people of the Magic Valley.

Yet near the Tropical Trail Highway, a family of nine lives in a two-room house — five of the seven children sleep in one room, the two oldest sleep outside in the old family car. Not far from that same highway is a migrant clinic where until recently a young doctor, Erik Svenkerud, practiced medicine. Dr. Svenkerud is now practicing in a remote region of Liberia, and expects to face the same challenges, indeed some of the same diseases he saw in south Texas. Svenkerud is not alone in his view of the region. Health researchers and professionals often compare health care problems in south Texas to those in developing nations.

Along a remote stretch of road in Rio Grande City, surrounded by cactus, sits a tar paper shack with four children out front, playing with the chickens. It is a familiar sight in the rural unincorporated villages called colonias that dot the valley. Approximately ninety-six percent of the residents are native Americans whose families have long-standing ties to this area. Many own their small, wooden homes. And according to a survey completed by the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs over half of those homes do not receive treated water.

In a 1975 report, US Secretary of Labor, Ray Marshall, then a professor at the University of Texas, stressed the significance of these findings. “Health care includes diet, water quality, sanitation... it does very little good for medical care to eliminate intestinal parasites in children, for example, if the environmental causes of those parasites are not eliminated.”

Solving this problem alone will take a major effort. Alejandro Moreno, director of Colonias del Valle, a grassroots organization aimed at giving the colonias a voice, estimates that “there probably are still 10,000 to 15,000 homes without water lines in the area.” And in the Triangle’s Starr County, where two-thirds of the population live below the poverty line, nearly half of the homes do not have flush toilets, according to 1970 Census figures.

Health care experts cite the living conditions of many south Texans as only one factor contributing to poor health. Poor diet, illiteracy, geographic isolation, inadequate prenatal care and a lack of health education also plague the rural population.

Dr. Paul Musgrave, a state health official, attributes the high incidence of typhus to the rodent population and unsanitary living conditions. Overcrowded housing is also a factor in the area’s high rate of tuberculosis, a contagious disease.

Leprosy is endemic to the region, which has the third highest incidence of the disease in the United States. This has state medical authorities on the defensive, according to one state health official in south Texas; “I wouldn’t give you the figures on leprosy if I had to.... I hate to see you mention it because there’s a lot of people who depend on the tourist trade down here.” Yet in spite of that burgeoning tourist industry, fifty-eight percent of the resident population earns less than $5,000 a year. And in this area rich with agricultural bounty, the LBJ study found seventy-five percent of the colonias residents — approximately the same percentage employed in agricultural work — suffering from malnutrition.

In 1970, Dr. Harry S. Lipscomb of Baylor University, testified before the US Senate about conditions in Magic Valley’s Hidalgo County: “I doubt that any group of physicians in the past thirty years has seen, in this country, as many malnourished children assembled in one place as we saw in Hidalgo County.” Lipscomb reported that “high blood pressure, diabetes, urinary tract infections, anemia, tuberculosis, gallbladder and intestinal disorders, eye and skin diseases were frequent findings among adults.

“We saw rickets, a disorder thought to be nearly abolished in this country, and every form of vitamin deficiency known to us that could be identified by clinical examination was reported....”

In the eight years since Lipscomb’s testimony, little has changed. A major problem is the scarcity of health professionals willing to work in south Texas. A 1973 study of health manpower in the state found that no county in the Triangle met the American Medical Association’s suggested physician-population ratio of 1 to 566. In Starr County, for example, there is only one doctor for every 6,900 people.

A more recent manpower survey revealed that several counties have only one resident physician, other areas none at all. Five regions of the area qualify as “critical health manpower shortage areas” (physician to population ratio exceeding 1 to 4,000) and are served by federally employed National Health Service Corps doctors and nurses. Several counties in the Triangle have only one dentist, and in rural areas mental health clinics (where they exist) are pitifully understaffed.

With health manpower both inadequate and maldistributed, with clinics, hospitals and doctors’ offices failing to plug the gaps in the health care “system” of south Texas, many unfortunate people fall between the cracks, like the bed-ridden elderly couple in McMullen County, the Zapata County child with rotting teeth, the ailing farmworker in Starr County.

“No Place for Orthopedic Surgery”

In the country around Freer, Brown has been the first and last hope for medical care — unlimited and unrestricted. He has spent five days and nights, “with time out only to shave,” caring for a critically ill heart patient. He and his staff have treated the fourteen victims, many severely injured, of a two-car collision outside Freer.

He has seen the government close the blood bank in Freer; he has stood by helplessly as his hospital staff unpacked the one pint of “reserve” blood from Corpus Christi; and more than once he has watched Freer’s volunteer ambulance drivers carry away bleeding patients he knew would die on the road. And throughout it all, Arly Brown is most frustrated “when you see an individual who has a significant problem and who needs a particular type of care that you just can’t provide.”

Sitting at his desk, beneath his diploma from the University of Texas medical school (issued “back when if you weren’t studying to be a neuropathologist, something was considered wrong with you”), Brown isn’t stingy with his thoughts on the practice of rural medicine.

“If you want to get rich as a doctor, a small, rural area is not the place to come to, because you’re not going to do it. A considerable amount of your work is charity (Brown estimates his at thirty-five percent), and you don’t have a charity hospital to send them to if they can’t pay. That’s just another problem in getting doctors to come to the country.”

For Freer’s country doctor there is no barter for medical care, though there are occasional gifts of venison, pickles and honey.

And although there is no place for orthopedic surgery, Brown’s first love, there is always the call to special duty: the pregnant horses, the snakebit dogs and humans and the injured deer.

“I’ve been told I’m a crazy idiot for staying around here by any number of my colleagues. I get it all the time, and I just tell them I’m not smart enough to leave,” he said, walking through the stillness of his hospital.

As for his colleagues, the doctor takes issue with those who “feel they cannot practice medicine short of being around a medical center.

“They have to stay right around the ivory tower and they feel it is the only place adequate medicine can be practiced. But I think they are badly disillusioned and making a bad assumption.”

Tags

Roy Appleton

Roy Appleton is city editor of the Denton Record-Chronicle in Denton, Texas. (1978)

Hilary Hylton

Hilary Hylton, formerly a staff writer for the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, is now freelancing in Austin. (1978)