Notes on the Early Black Press

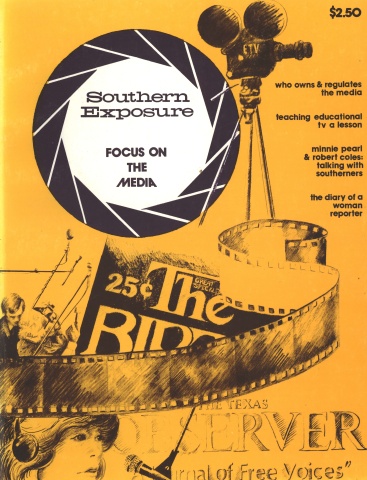

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

Near the close of the nineteenth century, Victoria Earle Matthews joined T. Thomas Fortune as co-editor of the Southern Age, a black newspaper in Atlanta. The auspicious union promised a combination of militant, highly professional journalism and independent political aggressiveness for the black press of the region. But like many black-owned papers of the period, Southern Age lasted barely a decade. Curiously, the economic pressures which forced many papers out of business, also encouraged editors to use women writers, and in the end, provided the opportunity for black women to play a crucial role in the development of the black press.

Victoria Earle Matthews, already a successful journalist, social worker, and author, had returned to the South to study the conditions of black women for the Federation of Afro-American Women. Born to poor parents in Fort Valley, Georgia, in 1861, "Victoria Earle" (as she became popularly known) was familiar with the region and its poverty. Only when she went to New York, did she find the education she wanted and a chance to begin her career as a "sub" for the large New York dailies, including the Times and the Herald. By the late 1800's, she received the respect of her peers, and leading white and black newspapers anxiously sought her writings. But her success and position as co-editor of the Southern Age were not unparalleled in black journalism.

To a number of women in the South, black-controlled journals offered a welcome alternative to the peculiar indignities of work in the domestic services. Talented, creative women who strayed from the narrow confines of conventional vocations to seek professional careers were generally ridiculed — especially in the South where women were slower to organize and assert their rights. In this context, the black press was atypical, for black women professionals received encouragement and honors in the field of journalism. Many women who began by helping their husbands run an under-financed newspaper learned the necessary skills to launch independent careers. Others endured the low wages, long hours, and uncertainty of continued employment so they could use this unique vehicle to address issues they felt strongly about. And in the instances where she gained control as editor, the black woman gained a degree of influence and power in her community that no other position open to women rivaled.

In 1891, I. Garland Penn, an early southern historian of the black press, devoted a full chapter in his volume The Afro-American Press and Its Editors to black women in journalism. Along with a lengthy profile of Victoria Earle Matthews, Penn included sketches of nineteen southern women who had distinguished themselves as contributors to the black press in the South. Some, like Alice McEwen, associate editor of the Baptist Leader, entered journalism through the church. Others moved into the secular press. For example, Mary V. Cook, using the nom de plume "Grace Ermine," edited a column for the American Baptist and for the South Carolina Tribune, and advanced to the editorship of the education department of Our Women and Children, an influential publication of the era.

Significantly, these women were pioneers in developing the southern black press as a force for shaping a black community.

After all, the South's first black newspaper, the New Orleans L'Union, had only begun in 1862, a mere thirty years before Penn wrote his book. Other journals sprang up and took their lead from the earlier northern papers whose very names asserted their dedication to the emancipation of all "persons of colour": Rights of All, The Elevator, Genius of Freedom, The North Star, Herald of Freedom, and, the nation's first black-controlled paper, New York's Freedom's Journal. The early southern papers, like their northern counterparts, occasionally lapsed into pretentious or pedantic writing; but they consistently addressed racial issues which white papers would not treat. Pushing the black cause in a hostile environment made journalism a risky business,* and while some support came from the Republican Party, the lack of advertising revenues or bank loans hastened the death of many black-owned papers. This marginal economic position combined with the lack of professionally-trained staff to offer a unique opportunity for black women writers and publicists.

Perhaps the most renowned of southern black women journalists is Ida B. Wells, editor of the Memphis Free Speech. Born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1862, Wells remained in the South until a white mob destroyed her newspaper office and threatened her life in 1892. Her only offense had been to editorially challenge an upsurge of lynching in Memphis:

Eight Negroes lynched since the last issue of the Free Speech. Three were charged with killing white men and five with raping white women. Nobody in this section believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men assault white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will over-reach themselves and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

An unwilling immigrant to New York, Wells received immediate moral support from T. Thomas Fortune of the New York Age, whose fame, notoriety, and sufferings for his militant journalism find few equals in the history of the black press. As Ida B. Wells wrote in her autobiography:

The Negro race should ever be grateful to T. Thomas Fortune . . . [He] helped me give to the world the first inside story of Negro lynching ... [and] printed ten thousand copies of that issue of the Age and broadcast them throughout the country and the South. One thousand copies were sold in the streets of Memphis alone.

Fortune had only recently returned to the New York Age from his tenure at Atlanta's Southern Age. Shortly thereafter, in 1898, his colleague, Victoria Earle Matthews died. In later years, Fortune began writing for the Norfolk Journal and Guide, and in 1923, he became editor of Marcus Garvey's New York paper, the Negro World. Meanwhile, the courageous and indomitable Ida B. Wells moved to Chicago where she raised a family, edited a newspaper, and almost single-handedly launched an international crusade against lynching. She remained active until her death in 1931, three years after Fortune died.

These three southern-born crusaders joined an impressive number of lesser known, though not necessarily less talented, journalists to inspire a tradition of black journalism that extends into the present day.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Gloria Blackwell. Black-Controlled Media in Atlanta, 1960-1970: The Burden of the Message and the Struggle for Survival. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 1973.

Anna Julia Cooper. A Voice From the South by A Black Woman of the South. The Aldine Printing House, Xenia, Ohio, 1892.

Alfreda McDuster. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Gerner Lerner, editor. Black Women in White America — A Documentary History. Pantheon Books, 1972.

I. Garland Penn. The Afro-American Press and Its Editors. New York Time and Arno Press, 1967 (originally published 1891).

Armistead Pride. A Register and History of Negro Newspapers in the United States: 1827-1950. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Northwestern University, 1950.

Emma Lou Thornbrough. Timothy Thomas Fortune: Militant Journalist. University of Chicago Press, 1972.

Tags

Gloria Blackwell

Gloria Blackwell is an assistant professor in the interinstitutional program in social change of Atlanta University and Emory University. She holds a Ph.D. in American Studies. (1975)