Notes of a Native Son

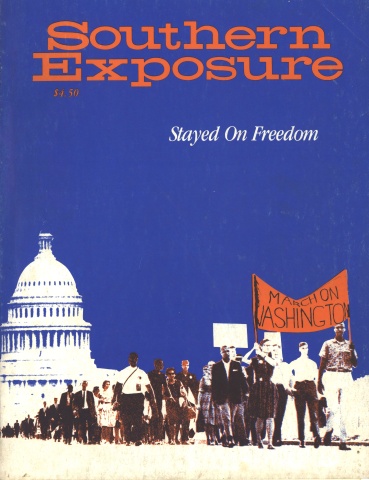

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

In retrospect, among the major criticisms of the Freedom Summer were that (1) it consisted of white people organizing in black communities, and (2) the white people came for only a few weeks or a few months in the summer, but the black people had to live their entire lives in those communities. The move towards black power, described by Cleve Sellers on page 64 was one result. The criticisms also led to white organizers beginning to work in their own communities.

Bob Zellner, a white Alabamian, had worked with SNCC for four years in the early ’60s. In 1967, he returned to his native state, this time to organize among white workers.

Bob Zellner

It was like coming back to a different world. I have talked with poor white farmers who, alone in their communities, send their children to Headstart centers run by black people — knowing that only here can the children get a start towards a decent education.

I have talked with white union members in the Deep South, some of them members of the Ku Klux Klan. They know that in a strike black workers will not support the union because it has betrayed them over and over. Yet they know that without the support of black workers their union will be broken and they will go back to starvation wages.

I have walked into union halls and talked with men like this. I make no secret of who I am. I tell them I worked for SNCC in the Civil Rights Movement and now I work with SCEF. I tell them frankly that if they do not want me to stay I will leave immediately.

They do not ask me to leave. Instead they say, “To hell with that. What can you do to help us on a strike?”

I understand that they let me stay because they think maybe I can be their negotiator with the black workers — because of my civil-rights experience. But I have to tell them right away I can’t be that — that no white man can ever again attempt to speak for the black community.

All I can do for them is try to explain what they will have to do if they want support from those black workers. Black people won’t make the first move, not any more. And when they go they must offer the black workers a whole loaf, complete equality in the union and all the benefits they have.

As we talk, something has happened to me, too. My first experience in the Movement was in McComb, Mississippi, in 1961. I was attacked by a group of white men who beat me into unconsciousness. Now I am back in the Deep South, working with the same kind of people who beat me then.

It is not that I never knew any Southern white people before. I grew up in Alabama. My uncle was a sharecropper. I have relatives who used to be in the Ku Klux Klan, and some still are. But I left this world and went into another one. I left because I knew I could not live in a world filled with racism and hate. I had to change that world. I left because I saw no hope of any of the people I had grown up with changing the world — and I saw that black people were going to change it.

Now I am back, and now I think that someday soon some of these people are going to help change the world, too. A few years ago I could not have talked with white people effectively about this. Black people in the South had not organized strength that the white people could see they needed. The Movement has changed all that.

Someday — maybe soon — I think I’ll be able to explain all this to some of the white people I’ve been talking with. I guess I’ve been a stereotype to them — one of those vicious civil-rights workers who the people who were running the South had convinced them were upsetting their “way of life.” I certainly had a stereotype of them — that they were people waiting on a dark road to kill me, and many of them were.

But now I have met some of them as human beings. We have had different experiences in our lives — but we’ve got lots in common. They want a decent life for their children, just as I do.

I think they soon may come to understand why I had to work with the black people in the South who were beginning to organize — will know, as I know, that until black people built up the strength they now have, there was no hope for any poor people to have the strength to win those decent lives we all want.

But I think of that time in McComb in 1961. I was in jail with Bob Moses, who was later to develop the historic 1964 Mississippi Summer Project. I remember Bob writing his words that later became famous: “This is Mississippi, the middle of the iceberg. . . . There is a tremor in the middle of the iceberg — from a stone that the builders rejected.”

I cannot say for sure, but it is just possible that today in 1967 there is a new tremor in the iceberg — from other stones that the builder rejected.