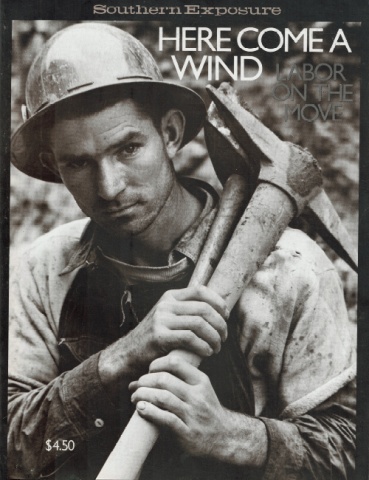

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

The South remains the last area of the country largely untouched by organized labor. Industries have left the unionized North in search of lower labor costs, better tax subsidies and other advantages that have in recent years given the South its well-deserved reputation as a corporate paradise.

Unions are slowly penetrating the South, especially those areas where the black worker is in the majority or where black and white coalitions are forged. If unions are going to survive and be successful in building a vibrant labor movement in the '70s and '80s, they must integrate their efforts with those of the entire black community. Past successes, from the Gulf Coast timber workers in the 1910s to Piedmont millhands in the 1970s (see other articles herein), have depended on the involvement of blacks in organizing drives and the black community's support. Plainly speaking, the future of organized labor in the South will hinge on the fortunes of the black worker.

I

To prosper in the region, unions must become viable institutions for the advancement of black people, instruments of liberation consistent with a tradition that translates economic and political interests into broad community issues. To understand why this is the case, it is necessary to probe history, tracing black people's fight for freedom and use of collective action that began when the slave traders unloaded thousands of Africans on American shores, deliberately mixing the different tribes to prevent cohesive rebellion. Thrust into an alien environment, black people developed a sense of community and togetherness which transcended natural barriers of language, customs and religion. When drums were prohibited by the slave masters, other survival mechanisms developed: hymn singing in the fields and Sunday afternoon gatherings where escapes were frequently planned.

Finally, slaves were only allowed to assemble in church on Sunday. These meetings became councils of rebellion. Black preachers like Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner led revolts in 1800, 1822 and 1831. Noted historian Herbert Aptheker has documented 306 major slave revolts prior to the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. And there were many other minor skirmishes, mass escapes and uprisings. The spectre of rebellion and retribution haunted every plantation, every farm, every place where black people were being held against their will.

In the Reconstruction legislatures of the Deep South, blacks helped pass progressive reforms, like free universal education and universal suffrage, which expressed their concern for the entire community. The power of blacks in the state houses faded quickly, along with their freedom, as the moneyed interests and the Klan regained control. Without an economic base, and with a new framework of social and legal regulations under Jim Crow, blacks were once again forced to rely on their own institutions for survival.

By 1919, Marcus Garvey's "Back to Africa" movement, which sought an organized response to segregation and related oppressive conditions, counted many Southern blacks among its two million adherents. At the same time, others like W.E.B. Dubois, William M. Trotter and Bishop H. M. Turner demonstrated the varieties of black protest and organization. Even black unionism was not without its proponents: 1925, A. Philip Randolph organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. During these years following World War I, when many blacks had tasted a measure of equality for the first time on the war front, the momentum for organized resistance increased. But militant protests in cities like Chicago and East St. Louis brought violent repression. The incidence of lynchings rose everywhere. In one case, during a riot in Tulsa, black neighborhoods were actually bombed by government airplanes.

In the South, some blacks turned to the rapidly developing labor movement to improve their lot. They found the best help in those unions which placed their demands in a large social context rather than in the narrowly conceived wage-and-hour issues. In the rural areas during the 1930s, blacks and whites joined together to form the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Alabama, Arkansas and Mississippi. A few industrial unions, especially the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers and the Food, Tobacco and Agricultural Workers had limited success in organizing urban blacks. But the labor movement was not yet ready to challenge institutionalized segregation. Jim Crow quotas in the workplace were challenged as well. When World War II depleted white manpower, blacks — like white women — fought for and began to get jobs in industry.

The most important history for the Southern labor movement to learn from is the civil-rights era of roughly 1955-1970. For it is in this period that the masses of black people were successfully and effectively mobilized in ways which labor unions must adopt for today's struggles. When Rosa Parks refused to sit in the rear of a Montgomery bus, her act of defiance and the Montgomery Boycott fanned the smoldering spark of freedom that burned within the heart of every black person. The level of upsurge and expectation rose in the entire community, not simply among a handful of leaders. The technique of nonviolent resistance pioneered by Martin Luther King, Jr., welded those on the forefront of the fight with others at home by emphasizing the moral correctness of the struggle and by placing demands within a widely accepted, yet highly principled framework (The Bible and the Bill of Rights); tactics were designed to allow and encourage mass participation — another critical lesson for labor today.

As the rhetoric of civil rights and the techniques of mass protest spread from community to community, a genuine movement developed. It was a time when thousands were involved in the fight to desegregate public accomodations from lunch counters to swimming pools, in voter registration drives throughout the old Confederacy, integrating schools, and in forming the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and other organizations that could carry the battle into new areas.

It was a time of high hopes, when barrier after barrier fell — or seemed to fall — when black people expected to participate fully in the life of their country. The courts, the press, the churches, all institutions of the establishment appeared to support the civil rights demands. People began to think heady thoughts — maybe; just maybe, the revolution was just around the corner.

The tide of reaction and resistance has snuffed out much of the hope that this society is capable of peaceful reform. In 1968, an assassin's bullet killed the Dreamer, and for the most part, the dream of a non-violent transition toward a more humane and egalitarian society. Yet the legacy of mass action, community organizing, and inspiring, yet concrete rhetoric remain for the activists of today to learn from and use.

II

Toward the end of the civil-rights era, Southern labor campaigns did draw heavily on the black community for their successes. Two particular struggles — the Charleston, S.C. hospial workers' strike of 1969 and the Charlotte, N.C. sanitation workers' efforts of 1969-70 — illustrate the strengths of the civil-rights/labor coalition. Both campaigns, though employing different methods, had several common factors: 1) the overwhelming majority of the workers were black: 2) the black community, largely through techniques gained from civil-rights campaigns, was mobilized to support the strikes; 3) the campaigns did not involve industrial unions, but those in the fast growing public sector, where working-class consciousness was strong because of the large numbers of national minorities within the ranks — Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos, and Native Americans.

In Charleston, some 500 workers, almost all black, worked in the lowest paying jobs at the state teaching hospital. In the late '60s, the workers developed local committees to improve their poverty wages of $1.30 per hour and their generally powerless position. They had heard of the militant hospital workers' union based in New York called Local 1199, and they asked them for help. Hampered by a South Carolina law that prevented state employees from bargaining a contract, 1199 officials knew that it would be difficult and would demand creative tactics and community pressure.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and 1199 had close ties, each having supported the other in previous battles including the Memphis sanitation workers' strike, where Dr. King was killed after he marched with thousands of supporters.

SCLC made a major commitment to Charleston. Ralph Abernathy and Mrs. King came to speak; Andy Young supervised the operation. The battle spread from the hospital to the churches and into the streets. Church meetings and nightly marches mobilized the entire community behind the fired workers. The national media came to the scene and highlighted the labor-community alliance. And the city had to construct outside pens for those arrested — workers and friends, mothers and babies, Abernathy and other leaders. Curfews, national guard, peaceful confrontations, mass marches and mass arrests became part of the new Southern labor movement.

But the law said no contracts were allowed. SCLC and 1199 sent out word for a final push. On Mother's Day of 1969, buses poured in from all over the South; people crowded into a hectic office. And the community turned out as never before. According to one march coordinator, "every able bodied person in the black community was there, some 15,000." Most people saw the campaign as a black-white issue. "White folks messin' over black folk, that's all it is," said many throughout the community. SCLC's leadership made a crucial difference. "If Abernathy's for it, then it must be okay," explained an elderly black man rocking on his front porch.

The hospital administration also felt the pressure from beyond the community. The national media had taken the Charleston strike across the country, inspiring other organizing. HEW used the weapon of federal funding to encourage the Medical College in Charleston to stop discrimination, and according to a recent account of a former government civil-rights officer, the White House wanted the strike out of the news.

Finally the hospital administration agreed to the union demands. The workers were rehired; wage increases were put in along with other protections. Without the legal right to a contract, however, building a permanent organization was difficult. Even so, the strike had won significant benefits for the workers and had precipitated many community gains, including voter registration drives and the election of black city council officials.

III

In Charlotte, N.C;, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) was organizing the sanitation workers during 1969-70, as part of a statewide effort which included the food workers at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and the garbage workers in Raleigh. The North Carolina statutes forbid contracts between municipal authorities and labor organizations. A labor union was in the position of having to force the municipal authority, in this case the Charlotte City Council, to 1) recognize the union; 2) make an informal agreement which both sides would agree to live up to; and 3) hold the council to the agreement with constant pressure, both from the community and from the threat of disrupting services.

Knowing all this, AFSME Local 1127 went out on strike on July 29, 1969. The largely black (85 percent) sanitation workers paralyzed the city by refusing to collect the garbage. Another problem underscored the racial character of the dispute. The courts had ordered cross-town busing to integrate the schools in the joint Charlotte- Mecklenburg County school system. White people were furious. The city quickly polarized, and an explosive situation arose. Sensing that a continued holdout of a practically all-white city council (one black out of seven) against the wishes of a practically all-black union could set off the conflagration, the council gave in after 38 days and recognized the union.

In this case, community pressure amid the specter of a racial conflict was a major factor in forcing the city to deal with the union. As the Charlotte Observer pointed out in its August 5, 1969, editorial, "The union used the thinly veiled threats of racial violence as a lever in negotiations. Several councilmen said they had a choice of giving into union pressure or focusing national attention on the city as racial unrest flared."

The tactic worked only briefly. The city council, influenced heavily by anti-union elements in this most antiunion of states, refused to live up to its agreements. A second and third strike occurred in rapid succession and were quickly settled. A longer and more violent fourth strike began in June of 1970. The city was determined to hold out at all costs, but the workers were equally adamant. During this last strike, several marches and demonstrations designed to mobilize community support took place for the first time. For example, one rally outside the city garage — conveniently located across the street from a nearly all black housing project — drew over 300 people.

The city had another trick up its sleeve. Not long before the fourth strike, the Southern director of AFSME, Jim Pierce, quit. He had provided the spark for organizing Local 1127, but differed with the union's national leadership. The city summoned his replacement to mediate the strike and found a more sympathetic ear. The new Southern director in turn convinced the workers that they had no recourse but to return to the job. The workers went back to work, but disillusioned, they withdrew from AFSME and became a local, independent union. Deprived of national affiliation and financial backing, yet bolstered by community support, the union hung on.

The fifth strike occurred on September 21, 1970, over demands for a dues check-off and dismissal of a supervisor who had fired several union members. Police cars blanketed the area around the sanitation garage, and shots were fired at the building. Inside, the men, led by business agent Eugene Gore and union president Bill Black, attempted to meet with the supervisor, who remained locked in his office. The men decided to march on city hall. They massed outside the garage and began marching two abreast toward downtown. Spontaneously, people from the Piedmont Courts and First Ward Area joined in as the procession moved through the area. Finally, the march, which had grown to 400 people, reached city hall. Despite the presence of a cordon of riot-equipped police, people continued to join in the rally. Eventually, some 500 people heard an hour or so of speechmaking and then marched back to the sanitation garage. The strike continued ten more days. On October 2, 1970, with their strike funds depleted and no national union's help, the men returned to work without winning their demands. The union has managed to hang on although in a vastly weakened position.

The effects of the union on the black community were far reaching, however. It served as an incubator and a catalyst for the development of militant black leadership which Charlotte sadly lacked. Several former sanitation workers became involved in civil rights activities in the city. In 1969, four black people ran for city council seats in an unprecedented move. All were grass-roots people and all were interested in radical solutions to the problems of the black community. Such a development could not have occurred without the militant labor strike of the sanitation workers.

These experiences illustrate that the black community can and will use new institutions like industrial and public service unions to raise their overall demands for social justice. But the attraction of a solid, well-financed, long-term organization, like a labor union, pales when their agenda appears narrow and compromising of larger concerns. Black people have a cohesiveness and closeness in relating community oppression in both spheres of their lives. To succeed, unions must appreciate this fact; labor drives must demonstrate to the black community that its struggle is labor's struggle, and that labor's demands relate to and can mobilize the community. Likewise blacks must demand and shape a labor movement that can utilize the energy and skills of black workers, that can forge a synthesis of the civil-rights and community-organizing style with trade unionism._

Tags

Jim Grant

Jim Grant, active in the Southern movement for many years, writes regularly for the Southern Patriot He participated in the Charleston hospital campaign and the Charlotte garbage workers strikes. Grant is currently a political prisoner in North Carolina, one of the "Charlotte 3." His case is being appealed. (1976)