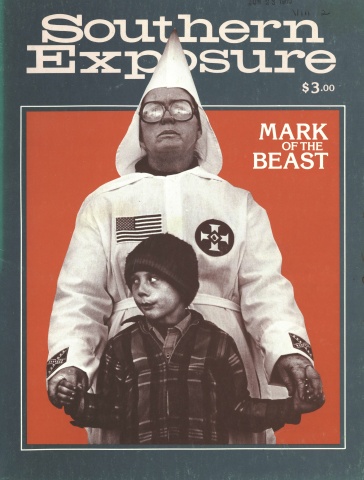

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

Editor's note: The spelling used in this article is not based on a strict phonetic system, but is merely intended to reflect the characteristic accent and rhythm of Mr. Lipscomb's speech. The authors acknowledge that no one speaks English exactly as it is ritt'n. The particularly musical quality of this story-teller's language, however, seemed to justify an attempt to capture the spoken word in writing.

Mance Lipscomb (1895-1976): Texas guitarist, songster, farmer and bluesman. Listed in Who’s Who In America. Bom by the Navasot River in an arm of the Brazos bottoms 75 miles northwest of Houston. Planted, plowed, chopped and picked cotton from 1906 to 1956. Played Saturday Night Suppers in the Brazos bottoms from 1912 to 1956, where he developed the knack for playing 18 hours straight and a repertoire of 350 songs spanning two centuries.

“Discovered” and recorded by Arhoolie Records in 1960. Played his first folk festival at Berkeley in 1961, before an audience of 41,000.

Went on to play most of the major folk and blues festivals from 1961 to 1973, including Berkeley, Newport, Monterey, Ann Arbor, Miami, Los Angeles and the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, DC. Played in most of the 48 continental states and Canada.

Recorded eight-and-a-half albums and appears on several blues anthologies. Starred in the biographical movie “A Well-Spent Life,” by Les Blank and Skip Gerson.

Some musicians Mance Lipscomb learned from: Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Willy Johnson.

Some musicians who learned from Mance Lipscomb: Taj Mahal, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Frank Sinatra, and Fiddlin Mary Egan of Greezy Wheels.

The following story tells why and how Mance Lipscomb brought his family to Houston in 1956, and what he found there. It is his unique story, while also being representative of the great rural migration of the ’50s into the Southern urban centers. It is excerpted from the forthcoming autobiography, I Say Me For A Parable, by Mance Lipscomb and A. Glenn Myers, and edited by Don Gardner. The biography is an oral history in Mance’s own words and in his own rhythm and musicality of saying things. In his speech, one can detect the counterpoint, accent and syncopation of the blues, its roots, and thus the roots of much of modem music. Especially if read aloud, one will sense and hear these same echoes and rhythmic reflections in the following excerpt.

So I had it hard all my days. Farmin, plowin. Cuttin and choppin an thangs. Playin them Saturday Night Suppers for fifty-nine years. But don’t never give up. A quitter loses. Just keep on. Doin the right thang. I lived so hard, til I cried. An I studied, an I sweated an give out. Tryin to make a increase. I buried my mother, my daddy, my sister’s kids. Still I was behind.

See, I was born a slave an didn know it. My daddy was eight years old when slavery time declared freedom. An the white people didn change it then. I call myself a slave until I got somewhere long about forty-five years of age. I had da go by the landowner’s word. Do what he said da git a home to stay in. We didn know nowhere da go. Now I say me for a parable, cause if I put you in this house an fasten you up, you caint git out. Well we wadn fastened up in the house but we was fastened up on their fawms. Not only me: all the colored folks.

Plantations was a big fawm. A plantation wouldn specify bein a plantation unless you had about twenty families on your place. They git fifty or maybe sixty hands on their place, an put old piece a houses up there some way. They furnish you feed an a team: You have to work their team. An their team pays for half a the money out that crop. An then they take half a the crop an pay for yo indebtments: You paid for your groceries, what clothes you wore, doctor bills, shoes — or whatever you got — outa yo half.

Sometime we come ta town, git what we need at a store. An sometime they haul em out from town in a wagon an put em in a commissary. Wouldn call it a store. It would stay lockt up til Saturday. You come up to the commissary an they issue your food out. Enter it on a book an you paid the end a the year.

How you gonna do any better when all the colored folks was doin the same thang? An they thought they was gittin somewhere. We was hemmed up. When I make my crop he would buy it. You couldn sell it. An he just give you what he want for it. Figgered it out his own way, you see. I jus kep acomin out in debt.

One year I cleared five hunud dollas. An he wanta keep my money an give it to me if I needed it, like he wanted da give it ta me. I told im “I thought you say I done paid you? An when I pay you: the money you owe me is my money. Not you keep it.”

Say “Oh you gonna throw it away.”

I say “Well if I do it’s mine.”

See after I done, made five hunud dollas, an cleared an paid the indebtments, to him what I owed him, was I out a debt? An that five hunud dollas was mine in the clear. But he didn want me ta have it, unless he give it ta me like he wanta. An keep me in debt.

An that was the man I workt under when I run off an slipt off, an went to Houston. An I was eleven years, an never did see daylight. No mown when daylight come. Here me up on the Bluffs in Washington County, an he had him a overseer — a strawboss — lived down in old Washington. Bossman stayed up in Dallas, didn hawdly come down here. What you call a absent bossman. He an his brothers got that gin up there on the Bluffs.

An I never could pay up my indebtments. Every year they run up higher an higher. See what he done: When I went ta his place I had leven head a cows an foe mules. An he bought a old tracta an brought it down here an sold it ta me for $500. He made me sell the mules an buy the tractor. An tuck mortgage on my cows.

He was allowin me $24 a month. An I git that once a month. But I would skip around an hunt, an pick up pecans, tryin to make my income ta take care a myself an Elnora, an all them kids. An I was give out. Man I done so much hard work for them it’s apitiful. I dont see why I’m livin taday.

In fifty-six I say “You know, it’s time for me to make a change. This man takin everythang I can inhurit — my crops — an they bring me out in debt mow and mow every year. I believe I’m gonna move up.” Talkin to myself.

One night I laid down, I just rolled an my wife woke up an says, “You sick?”

I say “I’m sick inside.”

She said “What? Inside?”

I said “I’m studyin my way out.”

Say “What you talkin bout, yo way out?”

Them days, when you go off an leave a man on a fawm: owed him a nickel, they would try to come git you. Make you come back. An if you didn come back — cording to where you was — he’d whup you an make you come back.

Now my daddy was a sensible man, but he wadn no good provider. But I listened, took what he said: “If you caint pay a man in the full, well you pay him in distance.” You know what distance means? You can walk out of it. Slip out of it.

I went, an studied that night, an that whole week. I didn eat much. I say “I’m tired a this man takin my earnins, an treatin me just like I’m a chile. I’m gonna move.”

My wife say, “That man goin come an git you.”

An I say, “That’s what he’ll have to do.”

That Sunday, I wrote my grandboy a letter. See I raised a grandboy went to Houston an had a job. I say, “Get a trailer, an come up here next Sunday evenin befoe night, an load my thangs up, an move me to Houston. Cause I’m tired a bein, you know, doin what I’m doin an treated like I am.”

An so, I played every Satidday night an Sunday for a beer joint for a dollah, or whatever I could git outa it. An I was settin there, when somebody said “Who is that comin yonder with a trailer?”

I say “I don know.” When he got closer to me, the mow I could reelize who it was. Cause he had a ’55 Shivolay truck. Got a trailer. I didn want the people to know what the boy was comin up there after cause the talk gits out.

I said “Ohh, that’s my boy Sonny Boy. You know what he huntin?” I throwed em off, I say “He huntin some cone. Any a y’all got any corn around here to sell?”

They say “No, we ain’t got none to sell.”

I say “Well that’s what he huntin.” But he’s huntin me. See, I knowed nobody didn have any cone cause it wadn the time a year fur it. So, he liked to drink beer an he stopt there. Come in say “Aw, here’s Daddy.” They all called me Daddy. That was my sister’s boy, Louis Coleman.

I say “Well, you wanta go up to the house?”

He say “I ...”

“Wait a minute. Dont say ‘I’ nothin. Just say you wanta go up to the house. You say sumpm I don want you to say.” An I pulled him on outa there, foe he let sumpm slip out.

Sundown come, we drove on up to my house. My thangs in there ready. My wife had packt up what she could: skillets an lids an dishes. Had over a hunud chickens. Had about 35 hogs. An I give some a them away an staked out what was left with Jude, that’s my son’s wife. An I said “Now when you sell em you give me some a the money. I’m gone.”

I had few people I could trust. I had some hogs weighed two or three hunud pounds. Two, three sows are goin find pigs. I killed about fifteen hens it was kinda cool you know, night: carried em to Houston put em in the deepfreeze. That’s what I lived offa about two weeks, them chickens.

Man I had buckets an pains on the trailer, loaded up just like cotton. Put them pains an lids and rockers an cains on the trailer an we had thangs wasted all the way from Washinton to Houston. An every time we hit a rough place: a pan or a bucket’d fall off, I said “Keep on.” But what we got there with, why we got there with that. I didn stop. Cause I uz runnin off. The Man liable to overtaken me, you know.

An day come: we was settin in Houston. An my grandboy couldn git in the house he rented for us, til day so they could come there an git the key for me. We got there on the truck.

Directly, Sonny Boy come up an sot out there with us. Said “Well, I tell ya: I aint got no place fur y’all to stay here tonight, but your thangs’ll be took care a. Aint nobody gonna bother em. I’m gonna carry you over here to some people’s house an let y’all lay down.”

Mownin come. Open the doe to the house, an we moved the thangs in there, an that where we stayed at. On East Thirty-Eighth Street. In nineteen fifty-six.

In Houston. I didn know one street from anothern. But I know I done left that fawm. Couldn find no job. There I was: stranded. I had foatteen dollas I never will furgit it, in my pocket. That foatteen dollas didn last over two days. I been buyin little bits an thangs toward them chickens I kilt. Said “Now I got to get me a job somewhere.”

So finely, this music is one thang all ways got me by. When I got to Houston, about the first week I got there, colored guy heard me playin. An news gits around. Say “You know, Lightnin Hopkins around here.” He was a famous player in Houston. He had all the places he want to play. Places he didn want to play.

Ohhh, they uz talkin bout “Lightnin Hopkins Lightnin Hopkins.” I had seed him two or three times. He didn worry me cause I had sumpm in my fingers for Lightnin. He couldn never play the music I play.

They said, “I want you to play, with Lightnin.”

I say “No, you want me to play with Mance. Last night he played with hisself.”

Say “Aww, I heard he could beat you.”

I say “Well, he’s got sumpm to do an I got sumpm to do. He’s doin his number, I do mine.”

Lightnin didn wanta mix up with me, he saw me play in Galveston. Nineteen thirty-eight, first time I seed him down there. 1 was seein Coon an Pie, my brother an sister. They’s twins, last ones born in the famly.

Finely, one night, a fella say “I’ll tell ya whut. I like yo music. I’ll give you ten dollas a night to play at my beer joint.” Oh man, that was a lot of money in them days. That’s mown I ever made in my life, ten dollas a night.

I went there on a Friday night, he say “You can come back Satidday night. Man, you make twenty dollas in two nights.”

Well that’s what I lived outa: twenty dollas, for about six months. My boy come down from Navasota an got a job, an my grandson he already workin there at a fillin station. So they kep me goin, along with that twenty dollas.

Finely old fella playin the fiddle — I was playin for his son had that little beer joint, right on the street — he played some real good fiddle. Old time fiddlin. His name Bill. An he got stuck off on me, playin that guitar behind that fiddle.

An the polices had that beat, you know. An they come up an down, check on thangs.

An the first thang you know I seed two polices, lookin in the doe. I said “Now, sumpm gonna happem here.” An I checkt up playin.

Two polices walkt in. I said “Uh-oh. I’m gonna git arrested here.”

He say “What your name, fella?”

I had to tell em, said “Mance Lipscomb.”

Say “We been listenin at you out there, on the street.”

I said “Listenin at me for what?”

He say “Boy, you play some damn good gittar.”

I say “Show nuff?”

Say “We had to come in there ta see how you look. We aint never heard no gittar played like that. We’ll walk that beat, up an down. An evertime we hear you playin a different song. This is our beat: go ahead on an play.”

I said “Thank you. I didn know what was up.”

Said “What’s up: we like to hear you play.”

Oh them people just dug in there, little small place hold about a hunud people. That boy did well: in a week’s time, all them joints round there broke up. Comin down to hear me play. The people had them little bands come over there an some of em like me an some of em hated me, cause I broke their joints up.

Finely one boy said “Mister, where you come from?”

I say “I come from Navasota.”

Say “We show do like yo music.” That’s one of the band boys.

Othern walkt up an say “Aww, he aint nowhere.” That was one of the band boys criticizin me.

An the othern say, “Man, he aint nowhere. He’s somewhere. We caint touch this man. That’s the reason we aint got nobody over at our place. All the people over here where this man at.”

Anothern say “You know whut? You done moved in on us, evawhere around in this precinct. We aint got nobody over there. This man done drawed all the people over here.”

An the boy what hired me, Milton say “Well, we got thangs goin, aint we? You doin right.”

I played there for him about six months. An his daddy joined in, commenced to rehearsin with me. See that fiddle was sumpm new to em round in Houston. An I would just bass him, backin him up an that fiddle would sound out so good.

The polices was dancin out on the street. Said “Boy, you got sumpm goin here! Where you git them people at?”

Milton said “My daddy playin the fiddle, an Lipscomb is playin the gittah.” I was playin lectric gittah then. Since about foedy-nine.

Say “Well, you doin good, since you have no fussin an flghtin here. Man we caint hardly quit comin up an down this street, listenin at that music.”

So, I stayed down in Houston, long about two years. An all the while, they up in Navasota, scratchin round for me, huntin me like a dog hunt a rabbit. He said I owed him five hunud dollas, an I dont owed him five cents. See they put that book on ya. An then “There, you done well this year. You may do better next year.” That’s what I got made to do better. But I was doin worser every year.

Then I come home — wait a minute, before I come home: this fiddler he was workin at the lumbayard. An he liked me, cause he wanted me ta be with him evy Satidday night.

He said “Boy, I can git you a job.” He was a handyman there, been workin there about ten or twelve years. Say “Do you know anything about the grades a lumba?”

I said “No. I don know one piece a lumba from another.”

Say “Well I’ll learn ya.”

I didn know much about no lumba deal, I was just workin tryin to make some money in Houston. So, that’s where I got hurt. An I like ta got kilt ta git where I am now. But you know when sumpm gonna happem to ya when it’s hurtin ya it’s fur ya. Good or bad. I'ut my bad bill made me whole, ta git good thangs to happen to me. Cause I was in the hospital with a fractured neckbone, an my awm in a sling.

So any way, first thang I was doin handin up lumba to the truck driver. I was on the ground, an the truck driver was on top a the truck, stackin lumba. An I was just crazy as a cricket.

Truck driver says “Man, hand me this two by foe.”

I’d git a two by six or a two by eight.

He say “Put that down! That’s not a two by foe!”

I workt myself down, pickin up the wrong pieces a lumba. Three days, I caught on. An they put me as a helper in a carbox, unloadin lumba off a train, up on the truck. I workt there six months. I was thrifty, I was a good man them days, I had plenty strength. I was goin on sixty years of age, then. Makin fifty-eight dollas a week. Man, I had money then. An all the boys commenced ta likin me, cause they heared me play on Satidday nights an I talk wid em an all.

Six months, it come one Saddy moanin, long about nine o’clock I never will furgit it: three trucks was there. We’d load this truck, an move the other one up. We had two truckloads a lumba that moanin. Two trucks out an the last load finish up by ten thirty.

An finely, the last truck driver pulled up to the side a the doe, an I was slidin the lumba off a roller dolly to him. He catch the end an whup it round.

The boy say “I done loaded the front end, Lipscomb. Wait a minute. I’m gonna pull the truck up, so I can load the back end.”

An I had foe pieces a two-by-foes, one on top a the other one, an I helt it with my hand on the dolly until he moved the truck up. An the end a that lumba, I stopt it inside. But the roller dolly, when he pulled up, was stickin out too fur. The truck hit it, goin by. An knockt that five hunud pound dolly down, in the flow. That thang cockt up an all that lumba — foe pieces — flew up the top a the carbox: alllllLLAM! an shot back by me, cut me on the leg an hit me on the awm. Knockt me out the bed a the carbox an fractured my neckbone. Didn break it, but knockt it outa place.

An then the boy what’s drivin the truck went on down bout ten steps further, an say “Well, we ready.” I could hear him.

An the man what handed some lumba to me, on the flow so I could shoot it out the doe, he heard the truck pull up an that lumba hit the back a that caw: A—llAM! Now I’m layin there in the flow. Out. Man lookt around an say, “HEY, MAN! COME HERE QUICK! This man in here dead!”

I was dead out but I could hear evathang. But I couldn move. That’s the last thang I remember him to say.

They commenced ta gittin under that plank an comin in there to get me. They rusht me to the first-aid place at the lumba cumpny. Wouldn haf ta go ta the hospital unless you was really injured. An I was show nuff injured.

So when I woke up I was layin on the operatin table. I’m layin up there with my leg buckled down, my hands buckled down. I commenced to twistin. An was a lady standin on this side, an one on this side: nurses.

An I opemd my eyes, said “What I’m doin up here? Well, wheresomever I’m at.”

An they smiled at me. Feedin me ice, an ice was comin out my mouth fastern you put it in cause: my mouth was closed, I was in a way of out. An they was pushin it in my mouth to keep the fever outa me. An they says “Oh, why you in good hands.”

I say “Well — good hands where? What all this water down in my bosom?”

They laught. They knowed I didn have no business knowin where I was cause a patient git scared when they find out they in a critical condition. An they tryin ta keep it hid from me. They did have it hid from me.

Finely they unbuckle them thangs off my awms an legs an I sot up on the table. I said “Can you tell me where I’m at?”

Say “You in the first aid hospital.”

I say “Yeah? Well I wanta go home.”

So it was a Satidday moanin about twelve o’clock when I got outa that first-aid place. My wife Elnora was sweepin up the house, when we drove in front a there just as nice an quietly. Thank two or three a my friends was with me. An one was drivin. An here my awm was bind up in a sling, an my legs was bind up so you couldn see my leg. An I was cut on the leg an I didn know that.

Myno come to the doe, and I was gittin out the caw: two men was on each side of me my wife says “Ohh, Lawd! Look at my husband! Lord, my husband is hurt!” An she went out the back doe hollerin she couldn stand that.

I said “Aw, I aint hurt.” Kids an the folks commence to comin, wanta know what’s the matter. She didn come back there in a hour or two.

An direckly she come in the room, an they had put me in the bed. She come to the door an lookt at me. Say “How you feelin?”

An I told her “I’m all right.”

When the news got over Houston, a whole lot a people was there, day an night. I was well cared fur. See I had a good reputation all my life. I had mow friends, in Houston might near I did in Navasota where I was raised. Cause I carried myself that way.

So about three or foe days, I commenced to movin round in the house, I thought I was all right. I went to the doctor at the first-aid place, an they checkt me. Say “Yeah, you all right. You kin go back to work, in about a week.”

Well I wanted my job cause I was makin seventy-five dollas a week! But they give me half a my wages to live on, you know. So I left the first-aid place — I could walk a little. An I walkt down on the streets to catch me a way home. Stood on the kohna.

After while a stranger come by, pulled to the side. Colored fella. Say “What’s yo name?” I tole im. He said “How’d you git hurt?”

I tole im.

He say “You been back on the job?”

I said “No. They give me a certain limit a time to come back.”

An he tole me said “Man, you don’t know what you can do.”

I said “What you talkin about?”

Say “Yo awm’s in a sling. You crippled in your leg. Ef you got hurt on the job, an then went back — I works for a lawya. I kin git you some money outa that hurt.”

I say “How’m I gonna git any money outa this?” I was green, ya know.

He say “You let me take you to my lawya. An this case you got: if you aint been back on the job, you kin show git some good money outa that. Dont you go back.”

I tuck him at his word. I said “Okay.”

“Monday I’ll be on my way down Houston, see my lawya, an I kin put yo complaint in, an he’ll vouch fur ya da git you some money outa it.”

I said “Well I ain’t got no money to pay no lawya.”

He say “You don’t need no money.”

So he carried me up there that Monday mownin. An his lawya was upstairs. We went up on the elevator. I didn know where he was carry in me. Houston’s too big for me.

Finely here his lawya settin up there in a chair with his foot up on the table an his legs crosst. I said “This man’s fixin ta shoot pool. This idn no lawya.” Thats what I had in mind.

An the colored fella knockt on the doe. He was workin fur that lawya. Git them clients to come in.

“Come in! Come in!” Lawya looks at me, an tuck his foot down off the table. “Oh. You got a good patient here.” Talkin bout me. Say “Yeah, well, what’s his name! Set down! Set down!”

I saddown, tole him my name.

He said “Yeah. You’s a good fella. You a whole lot bettern these fellas what I been takin cases, just perjured an makin me lie an do thangs.”

He lookt at me and said “When did you get hurt?” I said “I got hurt, on July the seventh. Ten thirty. On a Saturday.”

He never stopt writin. “M-hm. So you aint been back on the job?”

“No.”

An askt me a few mow questions, he wrote em down. An I give all those thangs straightened out. That was nineteen fifty-seven.

Said, “Well, if I take the case: fur a certain percentage.”

I say, “Well lawya I dont have any money.

'He say “Listen: I dont need no money. I got a case win. An if you need any money, tell me now an I’ll loan you some money.”

I didn say nothin.

So he told me ta go to a real hospital, so they could verify I was hurt. I stayed there, three weeks. Then that made that lawya had a strong case.

An about two weeks after that, the cumpny lawya come. To take a checkup on me. An had ta go through coat with my lawya an the cumpny’s lawyas.

It’s two lawyas: one is askin you one question one is askin you another. Cross-examine ya. That’s confusion, you see. No it don’t confuse me cause, I’m ware a them thangs. People try you out. I been tried out many cases. They tried me a lot a times ta doublecross me.

So my lawya an them got it all straightened out, an they laught it off you know, an drankin coffee. Guyin one another. One of em told my lawya say “You got this boy Lipscomb trained. You gonna make a lawya outa him.”

An he said “Well, I hope so. But I aint gonna let you doublecross im.”

So I stayed about two months before I heard from im again. An I thought probly they was gonna come across in two weeks. Well, they first offer you a settlement. An if you take that bid, they pay you off.

But that lawya set out to git something. He called me says “Lipscomb. I got a offer for seven hunud dollas on your case. But, I wont take that. I tole em ‘Go an come again.’ He’ll come back. They got three times to come here, an if they dont come to my requirements, then I kin sue em. They aint gonna stand no suein. It a big cumpny, an got good lawyas. They tryin you out, gonna see what would you accept.”

I said “Well, you the lawya. I’m just the patient.”

So they stayed away a certain length of time, an offered him eighteen hunud fur it.

He said “I hear you in this ear but I dont hear you in the other ear. I want to hear you in both ears.” So when he got to hearin in both ears that was the third time.

About six months: I was broke. But I tried to hang on, with my grandkids an thangs an let them took care a me. Well it was purty well gittin ready for Christmas.

An I had it to telephone my lawya I said, “I need a little money. I’m behind in the rent. An I dont have a job.”

He said “I tole you you could git some money the first day you come here.”

I said “Yeah, I done without it until now but, I need a little Christmas money.”

He say “How much you need?”

I say “Oh, about a hunud dollas.”

He say “Oh man, that aint no money. A hunud dollas wont go ten minutes with ya.”

I say “Yeah, but I aint got the hunud. I’ll take anything.”

He laught say, “Lipscomb, why dont you git you foe or five hunud dollas?”

I say “Oh, no man! I dont git no foe or five hunud dollas, in yo debt.”

He say “Thats yo money I’m payin you.”

I said “Well, I aint got no payment yet.”

He said “But you got a case. You just as good as got some money. Christmas, man! Git you some money.”

Well I didn see what he was feelin at. See he had a win case an I didn know it. I coulda got a thousand dollas, good as I did the hunud.

He said, “Why dont you take a hunud an fifty, anyhow? For Christmas?” An he fooled around an made me take a hunud an fifty, stid of a hunud. An that last me up until I went back to Navasota.

Cause I done tuck the lawya’s advice an come back here to Navasota, somewhere in August. They sunt me word of a man had some tractors wantin me to cut the highway. They knowed I could drive tractors purty briefly.

I come up here makin a dolla an a quota a day an, dolla an a half a day an I rose up to five dollas a day an I was gittin somewhere. I’m gittin rich five dollas a day.

An I kep aworkin on that highway. Said “Well, I just as well furgit about that lawya.” Cause that’s all I got outa that lawya, for about a year. I lived on that hunud an fifty, til I went to work on the highway. But you know I all ways had some place to play on Satidday night, little or much. An some time I lived pretty good outa it: seven dollas a nite.

So finely one Friday evenin, when I come offa work a man come down there on a bicycle with a telegram. An it said “A lawya something wants you.” I forget his name. An say, “Come at once.”

I say “Now I wonder what he want in a year’s time? I’d go through a motion in talkin to the other lawyas, an I’m tired a that. I aint gittin nothin outa it.”

But I took his advice. An the next mownin, I cot the seven o’clock bus, an went on down to Houston.

An went upstairs. He settin at his table, lookin out the winda. An I knockt on the doe.

He say “Come in!”

I opemd the doe, he turned around, said “Well doggone! Here’s old Mance! Boy, I’d a flew down here if I’d a been you.”

I said “How’m I fly down here? I aint no bird.”

He said “Git you a airplane.”

“Nooo, man I aint comin up here ona a airplane. I comin ta see what you want.”

Had a big ole envelope layin up on the table. He said “Well, here’s a present for you. Open that envelope.”

An I lookt over it. Opened it an that check was, thirty-five hunud an five dollas in there. Made out in my name.

An I went over to the bank an casht it an he counted up his money: I owed him that hunud an fifty dolla indebtment, an owed him for that lawya fee, an the hospital fee. That checkt me down from thuddy-five hunud to seventeen hunud an fifty dollas.

He didn do no purdy good job, he done a good un: thuddy-five hunud dollas! I appreciate what he done. He done sumpm for me that I couldn do for myself. An then I didn git all the money. But, it hadn been for him, bein a good lawya, an knowed his grounds, I wouldn a got nothin. See?

An that caused me to be right at the house I’m at now. I bought it all. Free an clear. I been livin there somewhere long about, since sixty in the fall I believe. So, you never know whats gonna happen to ya. But I can tell you sumpm: you just try da live right. One a these days a little right come comin to ya.

Tags

Mance Lipscomb

Mance Lipscomb (1895-1976): Texas guitarist, songster, farmer and bluesman. Listed in Who’s Who In America. Bom by the Navasot River in an arm of the Brazos bottoms 75 miles northwest of Houston. Planted, plowed, chopped and picked cotton from 1906 to 1956. Played Saturday Night Suppers in the Brazos bottoms from 1912 to 1956, where he developed the knack for playing 18 hours straight and a repertoire of 350 songs spanning two centuries.

A. Glenn Myers

A. Glenn Myers, a native Texan, folk musician and Vietnam veteran, met Mance Lipscomb in 1972 at a folk festival. He committed himself to being Lipscomb’s biographer in 1973, and lived in Mance’s homelands for five years. Since 1977, he has devoted all his efforts to the Lipscomb biography, with the aid of a grant channeled through the Texas State Historical Association. (1980)