This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 1, "Building South." Find more from that issue here.

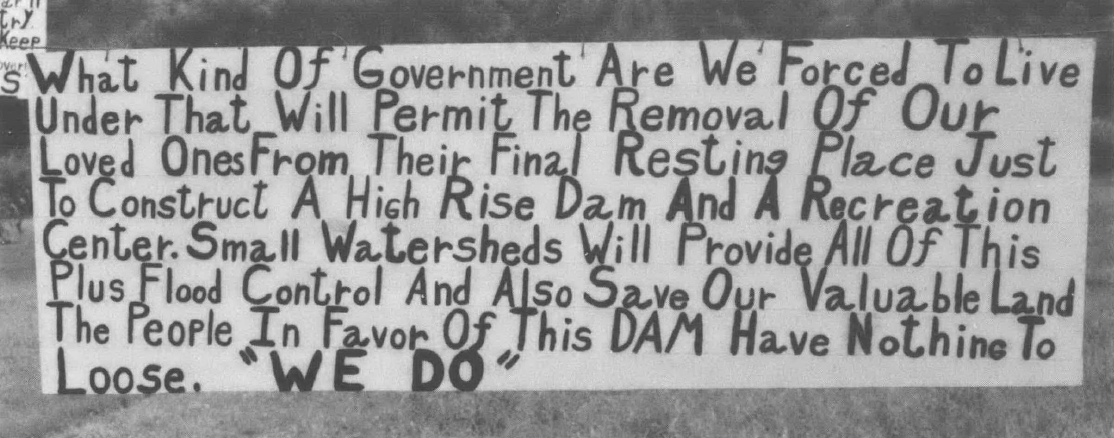

The scene was a high school auditorium in tiny Louisa, Kentucky, on the banks of the Big Sandy River. The occasion was a 1977 public hearing on the proposed Yatesville Dam, a $59 million flood control project of the United States Army Corps of Engineers. The principal speaker in support of the dam was the venerable Carl D. Perkins (D-Ky.), an ardent defender of the time-honored notion that “public works are good works.”

Perkins has delivered six Corps reservoirs to his East Kentucky district — dubbed “the liquid district” by a reporter — and he is pushing for the construction of several more. He has been returned to Congress 15 times since his election in 1948, and the casual political observer might readily assume that at least part of Perkins’ popularity springs from his love affair with the Corps and his passion for damming rivers and streams.

In the March, 1977, hearings at Lawrence County High School, though, Perkins’ constituents had not come to praise him for bringing home federal water dollars. Instead, they booed him into silence and allowed him to speak only after a Corps colonel reminded them that the congressman was, after all, their congressman.

The heckling of Carl Perkins is just one of numerous signs in recent years that a crack has appeared in the concrete foundation of the public works pork barrel system as it is executed by the Corps and other water resource agencies. Some pessimistic public works critics fear the crack is more like a hair-line fracture, because Congress continues to appropriate literally billions of dollars each year for a wide range of water projects, many of which are economic “turkeys” and environmental disasters. Yet it is also true that a growing and increasingly sophisticated opposition has undermined the “water pork” system in at least two major ways: first, by exposing the convoluted and self-serving methods used to justify water resource projects; second, by demonstrating that many water projects, far from improving the economic viability or quality of life of a particular community, often produce exactly the opposite effect.

While key Southern congressmen stubbornly resist reforms in water policy at the national level, Southerners across the region are organizing against water project boondoggles in their local communities. The effectiveness of these local efforts will determine the future course of this nation’s public works and water policies.

Public works are structures paid for by public dollars for public use dams, highways and housing projects for example. Pork barrel projects are public works which are authorized and constructed primarily because of political considerations rather than their value to the general public. The typical pork project is a water project. Each year Congress appropriates billions of dollars for navigation, flood control, water supply and other water resource projects constructed by the Corps and three other major agencies the Soil and Conservation Service in the Department of Agriculture, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in the Interior Department and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

With a workforce of 30,000 people, offices in all 50 states and an annual budget exceeding $3.8 billion, the Corps is the oldest and the largest of the water resource agencies. Dating back to the days of the founding fathers, the Corps was responsible primarily for navigation until the mid-1930s when Congress broadened its scope to include flood control, hydropower, recreation, irrigation, municipal and industrial water supplies, and fish and wildlife enhancement. The Corps operates in the Department of the Army, and the top Corps official is the Undersecretary of the Army for Civil Works.

The South corners more than its share of water resource projects. In fiscal year 1979, the Corps received 74 percent of the S2.2 billion allocated to active construction projects of the BLM, TVA and the Corps. Of this amount, less than $204 million, or 9.3 percent, went to 16 Northeast and Midwest states, while Alabama and Mississippi alone received $214 million.1 Fiscal year 1980 appropriations reflect the same prevalence of Southern projects. The total civil works budget for the Corps in 1980 is $2.8 billion, and over $1 billion of this, or 36 percent, is earmarked for the 11 Southern states. Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, Florida and Georgia ranked among the top 10 states receiving the most in Corps funds.2 Moreover, of the 10 largest Corps projects now under construction throughout the country, the first seven are located in the South (see chart). The South is, in effect, awash in Corps projects. From South Carolina to Texas, from Florida to Kentucky, the Engineers tinker with rivers and streams in a massive earth-moving effort that never ceases.

Water pork has a Southern flavor because Southern congressmen are the cooks, according to environmental lobbyists who have worked on Capitol Hill for many years. Southerners control the pursestrings in the Congressional system for mandating water projects. That system operates on two levels — authorization and funding. Every two years, Congress passes the mammoth Water Resources and Development Act authorizing billions of dollars of new projects. A project will usually be okayed by the Public Works Committees and authorized by Congress if the Corps (or another agency) approves it, if the local congressman supports it and if that congressman has supported the pet projects of his colleagues. Loyalty to the public works system is forcefully demanded by the public works authorizing committees, says the Enviromental Policy Center (EPC) of Washington. To get the committee to approve a project in his district, EPC concluded in a recent study, a congressman “must not vote to cut out a water project of another member no matter how bad the project might be.’’3 The name of the game is “I’ll vote for your project if you’ll vote for mine.”

Getting a project authorized is relatively easy because as often as not Congress willingly exempts bad projects from its own minimum guidelines. Getting a project funded for construction, however, is quite a different matter. Currently some 400 authorized projects have never received construction funding.4 The real power to pour concrete lies in the appropriations process which has been dominated by Southerners for many years. Representative Tom Bevill of Alabama succeeded Representative Joe Evins of Tennessee as chairman of the powerful Public Works subcommittee of the House Committee on Appropriations. Representative Jamie Whitten of Mississippi heads the full panel. Until last year, Senator John Stennis of Mississippi was Bevill’s counterpart in the Senate, succeeded by Senator J. Bennett Johnstone of Louisiana.5 Congressmen critical of water projects rarely get appointed to the public works subcommittees. Observes one environmental lobbyist: “The congressmen who go on the committees are the congressmen who are rolling the pork barrel.”

Recent maneuvers of Congressmen William Chappell of Florida and Gene Snyder of Kentucky underscore the importance of an assignment to a public works panel. Chappell, a member of Bevill’s subcommittee, is the primary obstacle to the de-authorization of the Cross-Florida Barge Canal, says Marjorie Carr of the Florida Defenders of the Environment (FDE). The canal, an environmentalist’s nightmare, was stopped by President Nixon in 1971 three days after FDE obtained a court injunction to stop construction. Florida’s governor, two senators and 13 of its 15 congressmen now oppose completion of the canal; the legislature has urged that the Corps proceed with restoration and disposition of project lands; and the Corps itself admitted in 1977 that the project should be terminated. Nevertheless, says Carr, Chappell is almost single-handedly blocking a de-authorization effort, using his influence as a member of the public works subcommittee.

In Kentucky, a $700,000 project to save a private Louisville housing development from a mudslide has received the support of Rep. Gene Snyder, a member of the House Public Works and Transportation Committee. Since the mudslide at Burkshire Terrace is not caused by stream bank erosion (in fact, there is no stream near it), the project does not come within the scope of Corps authority, but Snyder persuaded his colleagues to add the project to 1980’s $4.3 billion water resource bill anyway. “If we start to take care of every mudslide around the country, it’s going to take up all the revenues of the federal govenment,” Snyder admitted in an interview with The Louisville Times. “However, I’m employed to represent my people — that’s what they pay me for. I happen to be in the right place at the right time with the right friends.”6

Every president from Roosevelt to Carter has made some attempt to curtail the congressional excesses represented by Snyder’s “I-got-mine” attitude toward the federal treasury. Different administrations have sought to plug the leak by not seeking authorization for major new projects and by not requesting money for some already authorized. Congress merely circumvents the administration, dealing more or less directly with the water resource agencies. The old saw around Washington is that the Chief of Engineers answers to the public works committees, not the Secretary of the Army or the President.

President Carter intruded upon this hallowed ground in the early months of his administration when he conducted an economic and environmental review of 32 water projects already underway. As governor of Georgia, Carter had successfully blocked the Corps from damming the scenic Flynt River. As president, however, he ran afoul of Bevill, Whitten, Stennis and others when he recommended that 19 ongoing projects be halted and de-authorized. Surprisingly, almost half the House — 194 members — voted with him, enough to sustain a veto. In the Senate, though, the administration was forced to accept a compromise that continued funding for half of the projects, most of which were in states with senators on the public works subcommittee.7

The congressman who introduced the administration amendment to delete the 19 projects from the House appropriations bill was Representative Butler Derrick of South Carolina. The move was unusual because one of the projects — the Richard B. Russell Dam — lay in Derrick’s district. But a Senate compromise kept alive the dam, which will impound the last free-flowing stretch of the upper Savannah River, and it is now under construction. Derrick announced his opposition to the project after his own independent investigation showed that the 30-milelong reservoir, sandwiched between Lake Hartwell to the north and Clark Hill Reservoir to the south, would harm his third congressional district more than help it. Derrick says he received “a lot of unkindness” from many of his propork colleagues. “There is a group here in Congress that has spent a lifetime believing in the public works system, that that’s the way you get re-elected and that a member is entitled to a project in his district.”

The maxim that pork is good and necessary politics was disproved by Derrick in 1978, however, when his district re-elected him to Congress with an 84 percent vote, even though polls showed his constituents were evenly divided on the dam issue. He also challenged the popular belief that a public works project automatically aids a community. His arguments against the dam echo many of the points that have been made by Corps critics from other quarters:

Cost: Originally authorized in 1966 at $84.9 million, the dam was estimated at $276 million in 1977, and at $338 million in 1980. Derrick calculates the true cost will exceed $500 million.

Economic Effects: “Rather than attract industry, lakes repel it,” asserts Derrick. The project will create only 35 permanent jobs but threatens over 400 lumber industry jobs in three South Carolina counties because thousands of acres of forestland will be taken. And despite a Corps prediction that 441 of the 500-person labor force would be hired locally, “We’ve had a constant stream of complaints over the last year that the Corps’ contractors are not hiring local people. The construction companies bring in their own people. And none of the major contracts have been awarded to firms in our district or even in South Carolina that I’m aware of.”

Wildlife: “There is a strong chance that the Russell Dam will ruin bass fishing in Clark Hill Reservoir because of the lack of oxidation.”

Recreation: The Corps claims that visitor use of the reservoir will account for 12 percent of the project’s annual benefits, but Derrick disagrees. “I question the reliability of their figures. As far as I can see, they count people who ride across the dam on Sunday afternoon as using it for recreation. . . . Even the Corps studies indicate we have all the flatwater recreation we can possibly use in this area halfway through the next century.”

Energy: Primarily a peak-load hydroelectric power facility [which supposedly will provide 79 percent of project benefits], the dam will not be necessary, Derrick says, because demand forecasts by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission have dropped sharply since the project was first authorized 14 years ago. Further, Derrick cites a study by Dr. James Estes, a professor at the University of South Carolina, showing that if $300 million were used to insulate attics to a factor of R-19, the annual energy savings would be 21 times greater than the energy produced annually by the Russell Dam generators.8

A water project must be worth more than it costs to be justified for construction. The Corps must show Congress that annual benefits, calculated dollars, exceed annual costs over the life of the project. If project can return more than one dollar in benefits for every dollar in costs, then the “benefit-cost ratio” (BCR) is said to be “above unity” and the project is fundable. The complex and often unfathomable methods by which the Corps arrives at the BCR for water projects have been assailed by a broad spectrum of Corps critics, from environmental groups to the General Accounting Office to the Army Audit Agency. In some cases critics decry the cost-accounting requirements established by Congress or the Water Resources Council, a regulatory body composed of water agency heads. In other instances, they accuse the Corps of deliberately falsifying data to achieve inflated benefits and reduced costs. The 232-mile Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway in Alabama and Mississippi provides some examples of the range of these criticisms:

The Corps is allowed to count “savings to shippers” as navigation benefits. Fully 86 percent of the Tenn-Tom benefits accrue not to the general public but to the coal, grain and chemical companies who are supposed to use the canal and who theoretically pass the savings along to their customers. Shippers can save money by using Tenn-Tom instead of railroads, for example, because private barge lines which haul bulk commodities on the nation’s waterways pay no user fees and only a four-cent-per-gallon fuel tax. Attempts to shift the burden from the taxpayers to the users have always met a stiff resistance in Congress. “A free railroad for the barge lines” is the way critics describe the Tenn-Tom.

The Corps claims that 28 million tons of commerce will move over the Tenn-Tom in its first year of operation in the mid-’80s. Two-thirds of this tonnage would be southbound coal, nearly half of which (7.2 million tons) would be export metallurgical coal from the coalfields of northwestern Georgia, northeastern Alabama and southern Tennessee. Yet this same area has been producing only 1.5 million tons of export coal per year in recent years. The Corps scenario — and Tenn-Tom’s favorable BCR — require a 500 percent increase in export coal production in less than five years. Coal industry executives in southern Tennessee say it will never happen. Extraction problems, limited reserves, lack of adequate preparation plants and other factors indicate that the Corps is “pipe dreaming” if it believes these coal movements will materialize.9

When construction began on the Tenn-Tom in 1973, the cost was estimated by the Corps at $390 million. Today the official estimate is above $1.8 billion and will continue to climb. Inflation accounts for only a part of this 460 percent increase. Hidden costs, increases in the project’s size and shoddy engineering studies account for the rest. The Army Audit Agency charged in 1976 that the Tenn-Tom “was authorized on a conceptual design without benefit of sufficient detailed engineering and planning.”10 A Corps document shows, for example, that the Corps failed to perform adequate core drillings of the canal route through northeast Mississippi before construction began. What the Corps assumed to be 2.7 million cubic yards of dirt turned out on closer inspection to be rock, adding another $21 million to the cost.11

In calculating the BCR, the Corps can pretend that the discount rate — the cost of borrowing money — is lower than what it really is. Under a 1974 statute, Congress allows the Corps to use a fixed 3% percent interest rate to figure the cost of projects authorized before January 3, 1969.12 The annual average interest rate on 30-year U.S. government bonds surpassed 314 percent in 1957 and is now over 10 percent. Using the artificially low rate, the BCR for the Tenn-Tom, according to the Corps, is 1.3 to one. If the Corps had been required to base its figures on the real world cost of borrowing money, however, the project could never have been justified. As it is, the annual interest payments are grossly understated (to the tune of $200 million by one estimate), and by the time the project’s bonds are paid off the taxpayers will have paid B-as-in-boondoggle billions of dollars in interest payments over and above the final cost of the project.13

Politicians and local boosters who favor pork barrel water projects always claim their projects will attract industry, provide jobs and usher in a boom economy. Particularly in the case of recreation and flood control reservoirs, these predictions often are never realized. Norris Lake, the first reservoir constructed by the Tennessee Valley Authority, provides an example of how reservoir recreation affects the economy of a local area. Dr. Charles Garrison, economics professor at the University of Tennessee, studied Norris’ impact on income and employment in the three East Tennessee rural counties in which the lake is located. “Although Norris is one of the most popular TVA reservoirs,” Garrison concluded, “it was found that recreation’s contribution to the local economy had been negligible, especially when compared to either the positive effect of manufacturing or the negative effect of agricultural decline.” The lake, in fact, did nothing to reverse the out-migration patterns of the area, and other counties with TVA and Corps reservoirs have also suffered continued losses of population.14

While large-scale water projects frequently fail to boost local economies, critics also contend that certain types of projects can actually have strong negative impacts on a community.15 Perhaps the single most damaging aspect of the Corps’ water projects is the government’s approach to flood problems.

“Despite the huge outlay of federal funds for flood control projects, flood damages in the United States are getting worse, not better,” asserts Dr. Brent Blackwelder of the Environmental Policy Center in Washington, D.C. Annual flood damages averaged $504 million in the 15-year period prior to 1970, Corps statistics show, but then jumped to a whopping $2.3 billion from 1970 to 1975.16

Ironically, the flood control program itself attracts and then imperils the development which has inflated those flood control figures. Tom Barlow of the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington explains, “A lot of downstream development that takes place is encouraged on the understanding that floods will be prevented, but this is illusory. People are sucked in. Values of floodplain property go up geometrically, so there’s a much greater potential for flood loss, much more so than in the past when people were naturally wary of building on the flood plain because floods were frequent enough for them to know they’d be in trouble.

“Every time there’s a major flood disaster, Tom Bevill quotes a Corps figure claiming that Corps dams have prevented $60 billion in losses. In effect that makes our point; there is more potential for flood loss in flood plains that are supposedly protected but which could be struck at any point in time.

“All an agency does with a flood control structure such as a dam is to reduce the frequency of flooding, so that instead of a flood every five or 10 years you only have a flood — statistically — every 50 or 100 years. Mostly they design flood control structures that will take care of everything except a 100-year flood. The problem is, you can have a once-in-a-100-year flood anytime. It can occur one, three or 10 years after the flood control structure is completed.”

The nation’s flood control program, launched by the Flood Control Act of 1936, relies too heavily on building dams and channelizing streams and not enough on nonstructural solutions, critics contend. Alternative approaches include flood plain zoning and management of hazardous areas to prevent encroachment and development, flood proofing of buildings, the creation of greenbelts and streamside parkland which can withstand periodic flooding, flood warning systems, encouraging communities to participate in federal flood insurance programs, and the preservation of upstream wetland areas to retain and store runoff and prevent rapid release. “The nation will continue to witness more and more major disasters because the flood control program has failed to come to grips with the central problem of keeping development out of hazard areas,” says the EPC’s Blackwelder.

The futility of the federal flood control program is evident in the state of Kentucky, where over 280,000 acres of land are permanently under the waters of Corps, TVA and Soil and Conservation Service reservoirs. Another 230,000 are slated for purchase or inundation. The Corps spends over $70 million in the state each year, yet Kentucky was ravaged by floods in 1977 and 1978, making it the most flood-damaged state in the country. And according to the Kentucky Rivers Coalition, only one flood-prone town in the entire state is flood-safe as a result of an upstream reservoir.17

KRC’s Tim Murphy argues that the Corps’ flood control strategy makes no sense. “If you could control a high percentage of the watershed, or had a dam immediately above a town you wanted to protect, then you could say protection was provided.” But even in cases where this is true, major floods still occur. The Cave Run Dam, for example, controls 95 percent of the watershed of the Licking River above Farmers, Kentucky. After the dam was completed, Murphy recalls, “Farmers got within three inches of its record flood because of water from side streams between the dam and the town. It was as if the Licking had never been dammed at all.

“The logic of trying to protect a watershed from flooding by building a whole slew of dams is the logic of creating a permanent flood,” Murphy continues. “The term flood control is a misnomer. It is inevitable that rivers with flood plains will flood them.” Even the Corps cannot claim that communities are flood-proof, Murphy points out. The Corps’ so-called “flood-control benefits” are based not on the prevention of floods but on the money that could theoretically be saved each year by the reduction of flood heights in developed areas downstream from a proposed project. Thus the Corps claimed that 26 percent of the total annual benefits of the Yatesville Dam would have come from “flood control,” even though it would have reduced the 100-year flood at Catlettsburg, the nearest downstream community, by only 2.4 inches.18

The fact that many reservoirs do not solve the problems of serious flooding means that many flood-prone communities continue to be developmentally stifled. “Communities which desperately need new industry and economic diversification aren’t going to get it as long as substantial parts of residential, commercial and public service areas are prone to catastrophic flooding,” Murphy observes. And as long as “semi-useless” federal projects soak up federal money, worthwhile small-scale projects will go unfunded. Alternative localized projects like flood walls, local participation in the federal flood insurance program, and flood warning programs would be much more effective than the large reservoir projects, argues KRC, which has been pushing state and local governments to assume responsibility for developing their own solutions to flooding.

What are the prospects for substantive reforms in the nation’s water policy and in the Congressional pork barrel system? Representative Derrick is pessimistic. “I thought the system was changing for a while, but I’m not too sure anymore. We’ve had some effect on the overall policy, but the problem is, the Corps is politically powerful — it’s hard to find districts where the Corps doesn’t have something going. That’s the way it works.” There is plenty of evidence to suggest that Derrick’s skepticism is justified:

· A reform adopted in 1974 called for projects to be authorized in two stages — first planning and then construction. The idea was to prevent the construction of projects that didn’t meet minimum requirements, but the attempted reform backfired. The 1980 authorization bill, for example, okays 54 projects that still haven’t been fully reviewed.

· In June, 1978, President Carter proposed reforms in the evaluation and funding of water projects. In addition he proposed legislation requiring local and state governments to pay a greater share of project costs, including construction. The administration bill, while still alive in the Senate, has been “crushed cold” in the House.

· The $4.3 billion Water Resources Development Act of 1980 is viewed by pork barrel critics as an “affront” to Carter’s attempts at water policy reform. Though Carter proposes that projects must have widespread benefits, many projects in the 1980 bill are clearly intended for special interests. Fully 75 percent of the benefits of a project in Gulfport Harbor, Mississippi, for example, would go to the DuPont Chemical Company.

Despite Congress’ refusal to put a halt to pork, there are signs the system is weakening. Carter ordered the Water Resource Council (made up of water agency heads) to come up with stricter standards for judging the worth of new projects. While the new regulations have not been tested, many of them respond to suggestions made by water pork critics.

Congress has been unable to pass an authorization bill in the last two years. In 1978, the bill simply got lost in the final hours of the session. In 1979, however, the controversial bill never made it out of Senator Mike Gravel’s water resources subcommittee, an unprecedented delay. Active opponents of this year’s bill cover the political spectrum, ranging from Americans for Democratic Action to the National Tax Union.

Corps critics have long bemoaned the refusal of the Corps and/or certain congressmen to give up on unpopular or unsound projects. Now come the irate citizen and the tenacious citizens’ groups to match the Engineers’ staying power. In the last 10 years, reports EPC’s Blackwelder, over 80 projects have been halted nationwide, largely because of local opposition. Marjorie Carr of Jacksonville, Florida, who 10 years ago helped found Florida Defenders of the Environment, has been fighting the Cross-Florida

Barge Canal for 17 years. In Texas, the Corps has been pushing for construction of the giant $2 billion Trinity River Project, consisting of flood control levees in Dallas and Fort Worth, a 146,000-acre reservoir below Dallas, and a 363-mile flood control and navigation channel with 16 dams and 20 locks extending from Fort Worth to the Gulf on the Trinity River. The plan has been on the drawing board since 1965, but the Texas Committee on Natural Resources keeps erasing it. In referenda in 1973, 1976 and 1978, voters rejected proposals to provide the local costs for the project. On one of these the Committee had only 30 days’ notice, spent $15,000 compared to $400,000 by the opposition, and still won 56 to 44 percent. The Corps has now shelved the levees and the navigation component but continues to study the reservoir and flood control channel. Ned Fritz, 64, a founder of the Committee, says his group considers these the most damaging part of the project and vows to continue the opposition.

One of the most effective citizens’ groups in the South is the Kentucky Rivers Coalition, organized in 1976 out of a successful fight to stop a Corps dam at Red River Gorge in East Kentucky. A coalition of 20 landowner and citizens’ groups, KRC has stopped two additional Corps dams and been instrumental in organizing local communities to fight their own battles against the Corps. “Our job is to help people organize themselves to act in their own self-interest,” comments KRC’s Murphy. “We know that public concern is motivated not just by the abuse of power but by the absolute and fraudulent use of power. If it can be shown that their concerns and their basic way of life are threatened, then people have a self-interest to carry the fight against these projects to the county courthouse.”

As the national debate intensifies over water policy and public works boondoggles, the importance of well-organized and effective opposition at the local level becomes more apparent. Harmful and unnecessary projects are local issues requiring local opposition if Congress is ever going to give up the pork ghost.

Tags

David Massey

David Massey is the business manager of the Knoxville Gazette, a community newspaper, and a former reporter for The Mountain Eagle, Whitesburg, Kentucky. A sometimes free-lance writer, he has done extensive work on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. (1980)