This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains use of anti-Indigenous slurs.

Throughout the South, as in the rest of the nation, sports is one of the most important sources of popular entertainment. For most men and a growing number of women, sports provide opportunities to experience a sense of artistry and skill, profound emotional satisfaction and feelings of social solidarity that few other activities can match. People fishing from a rowboat or playing weekend tennis, people engaged in neighborhood softball leagues or following high school teams, whole cities and regions caught up in the fever of a pennant race or a bowl game — all know the kinds of community feeling sports can engender. For more than a few people, sporting activities have become a highlight of life.

Yet within this world, many destructive tendencies are at work, such as:

• the growing inequalities in the treatment of spectators;

• the undeniable “health and safety” hazards in modern organized-from-above sports; and

• the ongoing exploitation of athletes at the collegiate level.

Too often the hope of enjoying a weekend ballgame becomes a struggle to procure scarce and overpriced tickets or evade a local TV blackout engineered by promoters. Too often the ideal of fair competition becomes a credo of win-at-all-costs which can leave young athletes crippled, or even dead. Too often the American dream of success leaves thousands of hopefuls with shattered dreams and nothing to show for a childhood of practicing jump shots or chasing fly balls.

DEMOCRATIC ACCESS TO PUBLIC SPORTS EVENTS

Sports in the United States, whatever their origins, have always been enthusiastically adopted by lower-income people. Baseball began as a genteel game, but urban workers and farmhands embraced it wholesale after the Civil War. Football, at first an exclusive pastime of elite Eastern colleges, spread to high schools and sandlots until it became a symbol of working-class toughness and endurance.

As a result, the bulk of professional and college athletes in our most popular team sports are from working-class and poor families. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the South. A disproportionate number of college football players come from the coal and steel towns of Alabama and the cattle and oil towns of Texas. According to a survey made in the late ’60s, the five leading states in per capita production of professional football players were all in the deep South (Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Alabama and Georgia; Arkansas ranked eighth).

But if college and professional teams are drawn disproportionately from among the poor and the black, the audiences for their games are overwhelmingly white and upper middle class. Football and basketball seats often cost in double figures — too expensive for most blue-collar families, especially when the high costs of parking, scorecards, hot dogs and soda are added. The poorer fan is further excluded by the preferential treatment given season ticket holders, a practice which may violate the 1964 Civil Rights Act requiring equal access to places of public accommodation. Washington’s Robert F. Kennedy Stadium sells nothing but season tickets for Redskin football games and patrons have been known to pass on choice seats through their wills like private property, even though the stadiums are publicly owned.

At the exciting Atlantic Coast Conference basketball tournament each winter, the lion’s share of good seats go to boosters who contribute $100 or more to the athletic programs of member schools. In baseball, more than three quarters of all big-league season tickets are owned by companies. And in almost every spectator sport, most of the good seats, especially for important games, are purchased by corporations to hand out as “perks” to executives and visiting businessmen. Time and again the average fan, even if he or she wants to spend the money, can’t get near the action.

Moreover, a whole structure of social privilege is increasingly embodied in the design of arenas themselves. When St. Louis beer baron Gussy Busch first renovated Sportsman’s Park in the 1950s, he installed fancy “loge boxes” for wealthy corporate customers. Later, when Houston built the country’s first sports dome, the city fathers approved glass-enclosed boxes, with cocktail and restaurant service, where the rich could relax while watching a game. Other new stadiums have special restaurants and clubs for the wealthy, who — for a sizeable annual fee — can avoid mingling with the hoi polloi in the stands.

If there was ever a time when watching a sports event was a leveling experience, when the businessman and the bus driver rubbed shoulders and cheered together, that time is gone. Now the bus driver watches the game at home on TV while the boss is sitting in his executive box. The social dynamic of today’s arena makes a mockery of the democratic rhetoric that has always surrounded American sports.

Some persons have begun to mobilize for reform. With the help of the Nader-inspired sports consumer group, FANS (Fight to Advance the Nation’s Sports), the finances of professional sports franchises have become a major public issue. Groups can now work to eliminate or reduce season ticket sales, provide access to seats on a first-come first-serve basis and prevent the construction of special boxes, restaurants and clubs in stadiums built at public expense. Few such movements have arisen yet, but activists in Minneapolis recently prevented the construction of a new domed facility when a perfectly adequate stadium already existed. Residents of New Orleans, strapped with huge overhead costs for the extravagant Super Dome, may wish they had organized sooner. Wherever stadium construction is presently planned, as with the expansion of the University of Tennessee football facility at Knoxville, sports enthusiasts should demand an accounting of who will foot the costs and who will reap the benefits.

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY FOR ATHLETES

Our sports organizations, whether collegiate, professional or amateur, have tended to take the most talented youngsters out of the working-class community and thrust them into a playing field where — if they are lucky — they can achieve fame, money and a secure place in the middle class. This process, occurring over 100 years, has reinforced a sense of the openness of American society. Our great athletic heroes, with few exceptions, are people from modest backgrounds, colorful, unpolished and enormously appealing: such Southerners as “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, Wilma Rudolph, Sam Snead and Willie Mays all fit this mold. Their success tells every young person that he or she can “make it” too, whether in sports or some other aspect of life.

But the triumphs of Joe Namath, Muhammad Ali and Cale Yarborough also teach the lesson that success comes from individual skill, ruthless competition and an unsentimental willingness to live with pain. Athletes who are the products of this system learn to become accustomed to hostile and competitive relations with their peers and to define success almost exclusively in terms of cash. Though shrewd about individual money matters, such athletes have little experience in collective action and are often naive in other ways. Even if they successfully protect their pocketbooks in the short run, many outstanding athletes seem powerless to prevent the permanent damage of their own bodies.

The health and safety problems connected with organized sports start young. Some players shouldn’t even be on the field, like 15-year-old Timothy Young of Greenville, South Carolina, who collapsed and died last August after running “punishment laps” for the junior varsity football coach. His weak heart, caused by chronic pericarditis, had not been diagnosed in the routine physical at Carolina High School. Other players are the victims of poor equipment or improper training. Florida student Greg Stead had his neck broken in a high school football game in 1971, the same year that a precedent-setting liability suit was filed against one of the country’s 14 helmet manufacturers. Since then six companies have gone out of business, and the nation’s producers of football helmets face damage suits of well over $100 million.

The scale of destruction in football alone is staggering. Literally thousands of college players will be injured this season, some of them permanently, but the pattern of protest is often as futile as it is old. Georgia outlawed football as far back as 1897, after the death of quarterback Von Gammon. But the ban was only temporary, and since than as many as 18 Americans have lost their lives playing college football in a single season. Improved equipment and better training has only led to greater violence; two years ago Georgia lost five quarterbacks to injury in the course of the season.

It doesn’t get any safer as the players move higher up. Boston Patriot Darryl Stingley was paralyzed in a game last August. Later, while bargaining with the club owners on safety issues, NFL player representative Randy Vataha (a former teammate of Stingley’s) observed, “They’re afraid to take the violence out of pro football. After all, it’s a business, and when you are in business, your priorities aren’t always what they should be. It is characteristic of our society.”

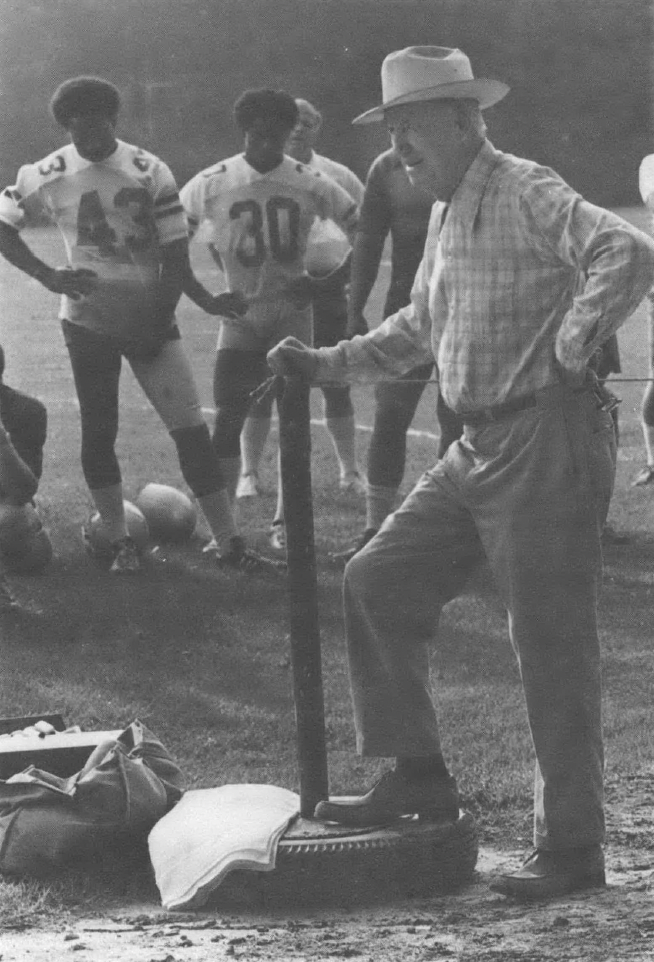

“Coaches see helmets and shoulder pads,” observes ex-Dallas Cowboy Pete Gent. “The bodies are just stuffing. And they can fill in more stuffing whenever they need it.” The players take steroids to gain weight and pop amphetamines to stimulate artificial levels of aggression; they suffer concussions, broken bones and repeated shocks to internal organs year after year. It is not surprising, therefore, that according to a Canadian physician quoted in Sports Illustrated, professional football players have a life expectancy of 58 years as compared to 70 for a normal American male.

The situation isn’t confined to football. As Bill Walton pointed out during his dispute with the Portland Trailblazers, the use of amphetamines, pain killers and muscle relaxers is also common in basketball. At too many levels in too many games, players are nursing major injuries by the end of the season.

So far very few sports veterans have found ways to overcome their individual cynicism, fatalism and frustration regarding injuries. But like others who earn a living through physical labor, athletes have begun to consider issues of occupational health and safety as fair and important grounds for organizing in the future. Fancier pre-conditioning programs, novel equipment design and expensive medical supervision are not entirely the answer. Instead, athletes need greater involvement in planning, workout and game schedules, a greater say in determining all the athletic rules and requirements which affect their physical and mental health, and a greater knowledge of their own bodies.

THE COLLEGE ATHLETE AS HIRED HAND

At what point do people who enjoy the competition and comradeship, the self-mastery and sheer physical joy of sport, become “workers”? At what point does play become labor? The answer is complicated, and varies greatly from person to person. But nowadays most people who try to get ahead by using their bodies begin — and end — that career in college.

For every athlete who uses the university as a bridge to a big-league contract, Wheaties commercials or a degree in law or medicine, there are dozens of others for whom the bridge collapses. When the rainbow fades, they discover they have been ripped off of the educational opportunity they were promised and have earned.

“College sports is professional sports in disguise,” says two-time All-American Dean Meminger, whose first hoop was a wire coat-hanger in rural South Carolina. “You bring them fame and notoriety, you bring them capital, and you provide entertainment for all those people, so why shouldn’t you get a share of the ‘profits?”

Supposedly, the payoff is in the valuable education and the coveted B.A. degree which caps it off, but many college athletes, after four years of unpaid service, end up with neither. As of 1978, according to the Washington Post, only nine of the 20 players whom Lefty Driesell had recruited for the University of Maryland basketball team had graduated from the school after playing for four years. At the University of Arkansas, according to a lawyer for three black athletes suspended from the football team in 1977, only one of 25 black athletes who had used up their eligibility received their degrees.

This betrayal of the purposes of the athletic scholarship — common throughout the United States — seems particularly severe in Southern state universities which recently desegregated. At the University of Texas at El Paso, not one of the five starters — all black — on the 1966 national championship basketball team received their degrees. According to 1978 statistics, two-thirds of the black athletes in the Southwest Conference majored in Physical Education and two-thirds never graduated, while among white athletes one-fourth majored in Phys. Ed., and one out of four failed to graduate.

In recognition of this problem, seven black athletes from California State-Los Angeles recently sued the school for $14 million on the grounds that their athletic scholarships were a fraud. Transcripts were allegedly forged, SATs and exams taken by third parties and professors pressured in order to get the players through. As a result, several were still functional illiterates after four years of college. Their lawyer, Michelle Washington, told reporters, “We lose out both ways, since the athletes didn’t get their promised education, and other students whose places they took never reached the college doors.”

Universities which derive revenues from their sports programs — and this includes most Southern state universities — will resist being held accountable to high academic standards and proper teaching for their athletes. To get such institutions to make a commitment to graduate their athletes requires massive political pressure from coalitions that include faculty and student organizations, civil liberties groups and sympathetic state legislators.

A LEGACY OF DISCRIMINATION

The problems mentioned here only scratch the surface, only solutions are not easily found. But the troubling dilemmas of sports, like the political problems in the wider society which they reflect, can be addressed through individual commitment and collective action. As Jackie Robinson showed a generation ago, changes in athletics can help change the culture. And this generation has its own unfinished sports agenda.

The struggle for full participation of women in sports, for example, centers on the enforcement of Title IX, federal legislation requiring equal opportunity for women in the distribution of athletic resources. Although athletic directors from the university “sports factories” are making a concerted effort to water down Title IX’s impact, women have been able to use this legislation to force universities to expand greatly their intercollegiate and intramural programs for women.

Right now there are two main fronts to fight on: putting pressure on the Congress to strengthen, rather than dilute, Title IX and initiating lawsuits on a local level to force compliance with the statutes. Feminist organizations and their allies have an excellent record in winning such suits. If you’re ready to help and can spare four dollars, the Women’s Equity Action League (733 15th St. NW, Washington, DC 20005) has put together a loose-leaf kit on “Women in Sports” with articles, charts, laws and facts that makes a great place to start. This is an opportune time to set up Title IX enforcement committees in local communities, both to aid the federal lobbying effort and to improve women’s access to athletic facilities in schools and neighborhoods.

Opportunities to stand up against racism may seem less straightforward now than when Jackie Robinson was a schoolboy in Cairo, Georgia, but the struggle is far from over. Michael Washington has shown recently that the percentage of blacks in big-league baseball has declined markedly — overall and at every separate position — over the past decade.

PERCENTAGE OF BLACKS IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL

Position 1960 1968 1977

Pitcher 3% 9% 5%

Catcher 11 12 4

Shortstop,

2nd, 3rd Base 11 23 10

First Base 17 40 21

Outfield 24 53 44

Total Players 12 22 16

Managers 0% 0% 0%

So you might begin by ordering a copy of Washington’s excellent pamphlet, The Locker Room is the Ghetto, from Equal Rights Congress, PO Box 2488, Loop Station, Chicago, IL 60690 ($1.50). Then tear out its back page, which invites you to write down your personal experiences with racism in sports. Or contact ARENA, the Institute for Sport and Social Analysis (PO Box 518, New York, NY 10025), which publishes the Journal of Sport and Social Issues. ARENA members were active in last year’s important boycott of a Davis Cup tennis match in Nashville against representatives of South Africa’s white supremacist majority regime. Racism continues to infect sports on an international scale, and they will need help from all of us in the future.

All these issues may seem vast and intractable. But they are also issues where change is both necessary and possible, and where people have begun to organize to prove it. All around the country, organizations like Sports for the People (391 E. 149th St., Room 216, Bronx, NY 10455) may be stronger and more numerous by the 1980s. And Southerners, as they rediscover, explore and criticize their own rich sporting heritage, may find themselves in the thick of yet another movement for human rights.

Tags

Mark Naison

Mark Naison was a varsity athlete in college; he now teaches at Fordham University and writes on sports for In These Times. (1979)

Mark Naison teaches Afro-American Studies at Fordham University in New York, and is an editor of Radical America. His research on southern radicalism led him to the Williams, with whome he has worked closely for the last three years. (1974)