This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Being a writer from the South and wanting to be published by a major publishing house has always meant sending your manuscript north, usually to New York or Boston. Being identified as a Southerner by a publishing establishment that has no links with the South has put many writers in an uncomfortable, even compromising, position. Flannery O’Connor’s words on her struggles as a writer speaks tellingly about this situation: “If you are a Southern writer, that label, and all the misconceptions that go with it, is pasted on you at once, and you are left to get it off as best you can. When I first began to write my particular bete noire was that mythical entity, The School of Southern Degeneracy. Every time I heard about The School of Southern Degeneracy, I felt like Br’er Rabbit stuck on the Tarbaby.”

Southern writers these days face an even more menacing editorial reception than O’Connor did in the ’50s, for now most publishing houses, which are still located up north, are controlled by corporate conglomerates like International Telephone and Telegraph and Music Corporation of America. As Forbes magazine’s most recent annual report on the publishing industry says, “It’s hard to find an industry that has been picked cleaner by the conglomerates than book publishing.” It’s so true. Since the early 1960s, when Random House absorbed Alfred Knopf, the publishing industry has been marked by a relentless series of mergers and takeovers, the end result being that scores of once private, individually owned publishing houses have fallen under the ever-enlarging umbrella of corporate ownership. A few examples illustrate the trend: CBS now owns Fawcett Publications, Popular Library and Holt, Rinehart & Winston; MCA owns New American Library, Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Berkley Books and G.P. Putnam’s Sons; ITT owns Pocket Books and Simon & Schuster; and Time, Inc., owns Little, Brown & Co. and Book of the Month Club, Inc.

While not all major publishing houses are owned by conglomerates, many that have remained independent, such as Doubleday, McGraw-Hill, Harper & Row and Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, have broadened their business interests, becoming conglomerates themselves. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, for example, has acquired more than 30 companies, including such un-literary enterprises as Sea World, Inc., a marine amusement park, and Captain Kidd’s Seafood Gallery, Inc., a California fast-food chain. The only major hardcover book publishers that remain both free from conglomerate control and uncluttered with other business pursuits are Crown; W.W. Norton; Farrar, Straus & Giroux; Houghton Mifflin and Macmillan.

This move to conglomerate ownership has had profound effects on the publishing industry, not the least being the scads of money that have poured in from the parent organizations. Most of this money has been directed into the discovery and promotion of what publishers call the “big book” — the blockbuster which floods the market place and which inevitably is made into a major movie and then sold to a television network. Incredible sums of money are involved in this process. Not too long ago, for instance, Bantam Books bought the paperback rights to Judith Krantz’s novel Princess Daisy — for over $3.2 million. Only with the backing of large financial corporations can money in such amounts enter the publishing marketplace.

Pursuit of the big book has created a situation in which a number of publishers are placing a great deal more time, energy and money into making sure that a book’s financial statement rather than its text reads well. Not that publishers haven’t all along been concerned with making a profit; they too, obviously, have had bills to pay. But bending under the pressure of parent companies, which have brought into the publishing industry a revolutionary overhaul of its once simple and often whimsical marketing techniques and strategies, many publishers now have expanded their promotion departments so that they — rather than the editorial offices — are the hub of the operation. As a result, editorial standards have dropped. Copyediting is often left undone. Editors are evaluated not on their literary discoveries but on the financial statements of the books they have recommended. With the increased presence of Hollywood in the publishing industry — Gulf & Western owns Paramount Pictures; Warner Communications owns Warner Books; MCA owns Universal Pictures — this has become the era of the package deal, in which the production and promotion of books into movies, and oftentimes into television series, are intricately linked. This media alliance has gone so far that it is not unusual for representatives of the various industries to sit down together and “generate” a product. With a bare plot in hand, these wheeler-dealers will hire an author to write a book and a screenwriter to complete a script, and then, when their products are ready to go, they will orchestrate an elaborate promotion schedule whereby the appearances of the book in hardback and then paperback are timed in such a way with the movie that the three will promote each other over an extended period. Sometimes the book appears first, sometimes the movie. The process usually completes itself with a new round of reprintings when the movie finally appears on television.

For authors, this emphasis on the big book has created a brutal caste system. At the top rest a relatively few authors who are making incredible sums of money (Judith Krantz, for one); these are the ones who, at their publishers’ urging and coaching, are running themselves ragged, crisscrossing the country in search of radio and television talk shows where they can plug their books. These are the writers of bestsellers — or books their publishers foresee as potential bestsellers. In contrast to these elite authors, those writers on the lower end of the caste system — particularly new writers trying to get their first books published and those known in the trade as “middle” writers (those who have shown some potential, have published a book or two, but have not reached the bestseller lists) — either are not getting published or, if they are, are saddled with limited press runs and meager advances.

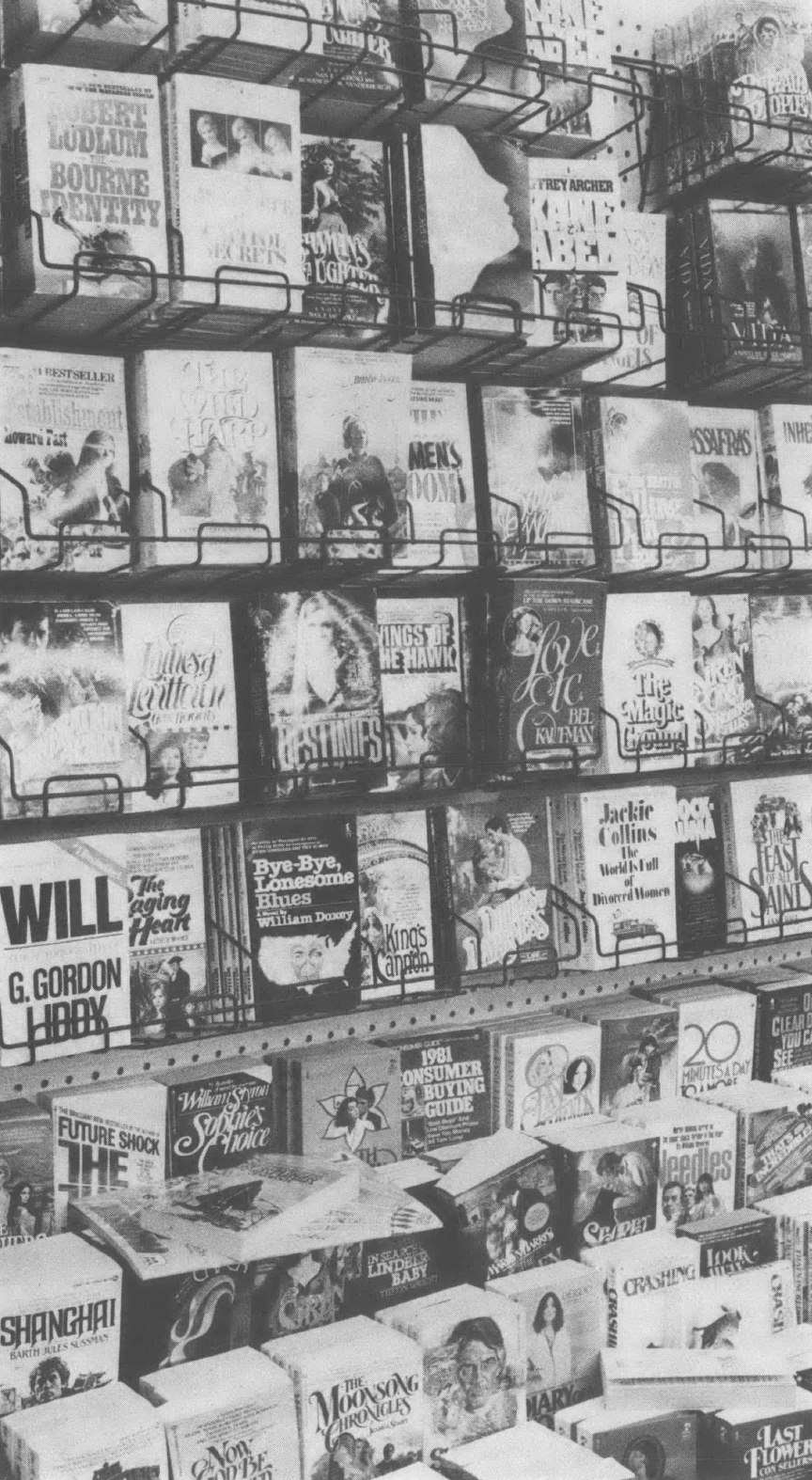

Adding to the plight of the struggling writer is the recent dominance of the bookselling marketplace by chain bookstores, such as B. Dalton and Waldenbooks, where the standard fare is bestseller, bestseller and best seller. Chain bookstores for the most part stock only what they think will sell fast, and when books don’t perform according to management projections (B. Dalton’s has a computer hook-up in every cash register in each of its stores, and therefore its executives know at all times exactly how many copies have been sold of every book stocked in their nationwide inventory), they are yanked in favor of more popular titles.

To make matters even worse for the non-elite writers, a recent Internal Revenue Service decision prohibits publishers from depreciating books stored in warehouses unless they are destroyed or sold at discount. This ruling will undoubtedly discourage publishers from taking chances on books that may not sell out quickly and will further Emit press runs on those that they do decide to go with. The publishing industry is in the throes of dramatic changes which are having profound effects on what reading material — books and otherwise — is being made available to all of us. In this section are a number of testimonies from this new conglomerate industry. In the excerpts from Thomas Whiteside’s essay, “Onward and Upward with the Arts — Book Publishing,” which originally appeared in The New Yorker, those involved with and those who have dealt with the major publishing houses speak on what is happening there. John Beecher’s “On Suppression” discusses the problems he had — and his struggles are typical of many authors’ — when his publisher brought out but refused to support his Collected Poems. On an upbeat note, Judy Hogan of Carolina Wren Press and Tom Campbell and John Valentine of the Regulator Bookshop describe their efforts at independent publishing and book selling. Little wonder in this age of conglomerate control that Hogan, Campbell and Valentine see their ventures not only as important in terms of achieving personal fulfillment but also in maintaining truly free and high-quality literary expression.

Tags

Bob Brinkmeyer

Bob Brinkmeyer, a long-time friend of the Institute, teaches English at North Carolina Central University and has published extensively on Southern literature. This summer he hopes to perfect his jump shot and bring up his batting average in City League softball play. (1981)