This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 3/4, "No More Moanin'." Find more from that issue here.

Among the literary figures that emerged from the all too brief, black-cultural upsurgence of the Harlem renaissance, Zora Neale Hurston was one of the most significant and, ironically, one of the least well known. She was one of the first black writers to attempt a serious study of black folklore and folk history and, as such, was a precursor of the interest in folkways that shapes much of contemporary black fiction. Her comparative present-day anonymity, then, is surprising, but is perhaps explained by the complexity of her personality and the controversy that attended her career.

Writing in the May, 1928, edition of The World Tomorrow, Zora Neale Hurston made the following observation about herself: “Sometimes I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can anyone deny themselves the pleasure of my company!” This is the kind of remark that one came to expect from Miss Hurston, who is remembered as one of the most publicly flamboyant personalities of the Harlem literary movement. She was very bold and outspoken, an attractive woman who had learned how to survive with native wit. She approached life as a series of encounters and challenges; most of these she overcame without succumbing to the maudlin bitterness of many of her contemporaries.

In her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, she explains her life as a series of migrations, of wanderings, the first of these beginning with the death of her mother. She then went to live with relatives who very often could not relate to her fantasy-oriented approach to life. Consequently, she was shuttled back and forth among relatives, who found her a somewhat difficult child to rear.

She was totally dependent upon them for survival, but she refused to humble herself to them:

A child in my place ought to realize I was lucky to have a roof over my head and anything to eat at all. And from their point of view, they were right. From mine, my stomach pains were the least of my sufferings. I wanted what they could not conceive of. I could not reveal myself for lack of expression, and then for lack of hope of understanding, even if I could have found the words. I was not comfortable to have around. Strange things must have looked out of my eyes like Lazarus after his resurrection.

She was fourteen years old when she began taking jobs as a maid. Several of these jobs ended in disappointment. She was in a difficult position. She was a Southern black child who was forced by economic necessity to make a living. But if given a choice between performing her duties as a maid or reading a book from the library of an employer, she almost always chose reading the book. She describeds this period of her life as “restless” and “unstable.”

But she was finally fortunate enough to acquire a position as maid to an actress. This position represents a significant break with the parochialism of her rural background and opens the way for her entry into creative activity as a way of life. Here, at last, she could exploit her fantasies. Here she could be the entertainer and the entertained. And most importantly, for this small-town Southerner, she could travel and seriously begin to bring some shape to her vagabond existence.

Black people have almost boundless faith in the efficacy of education. Traditionally, it has represented the chief means of overcoming the adversities of slavery; it is the group’s main index of concrete achievement. Zora shared that attitude toward education. It represents a central motif through her autobiography. Education, for her, became something of a Grail-like quest. As soon as she was situated in a school she would have to leave in order to seek employment, usually as a maid or a baby-sitter. But her life experiences and her reading were an education in themselves. By the time she entered Morgan College in Baltimore, she was sophisticated, in a homey sort of way, and tough. She had personality and an open manner that had the effect of disarming all of those who came in touch with her. But none of this would have meant anything if she had been without talent.

After a short stay at Morgan College, she was given a recommendation to Howard University in Washington, D.C. There she soon came under the influence of Lorenzo Dow Turner, who was head of the English department. He was a significant influence. Like Leo Hansberry (also of Howard), Turner is one of those unsung heroes of Afro-American scholarship. He is the author of an important monograph on African linguistic features in Afro-American speech. It was while Zora was at Howard that she also published her first short story, "Drenched in Light,” in Opportunity, a magazine edited by Charles S. Johnson. Her second short story, also published in Opportunity, won her an award, a secretarial job with Fannie Hurst and a scholarship to Barnard. There, she came under the influence of Franz Boas, the renowned anthropologist. It was Boas who suggested that she seriously undertake the study of Afro-American folklore—a pursuit that was to mold her contribution to black American literature.

Zora Neale Hurston was born in 1901 in the all-black town of Eatonville, Florida. This town and other places in Florida figure quite prominently in much of her work, especially her fiction. Her South was, however, vastly different from the South depicted in the works of Richard Wright. Wright’s fictional landscape was essentially concerned with the psychological ramifications of racial oppression, and black people’s response to it. Zora, on the other hand, held a different point of view. For her, in spite of its hardships, the South was Home. It was not a place from which one escaped, but rather, the place to which one returned for spiritual revitalization. It was a place where one remembered with fondness and nostalgia the taste of soulfully prepared cuisine. Here one recalled the poetic eloquence of the local preacher (Zora’s father had been one himself). For her also, the South represented a place with a distinct cultural tradition. Here one heard the best church choirs in the world, and experienced the great expanse of green fields.

When it came to the South, Zora could often be an inveterate romantic. In her work, there are no bellboys shaking in fear before the brutal tobacco-chewing crackers. Neither are there any black men being pursued by lynch mobs. She was not concerned with these aspects of the Southern reality. We could accuse her of escapism, but the historical oppression that we now associate with Southern black life was not a central aspect of her experience.

Perhaps it was because she was a black woman, and therefore not considered a threat to anyone’s system of social values. One thing is clear, though: unlike Richard Wright, she was no political radical. She was, instead, a belligerent individualist who was decidedly unpredictable and perhaps a little inconsistent. At one moment she could sound highly nationalistic. Then at other times she might mouth statements that, in terms of the ongoing struggle for black liberation, were ill-conceived and even reactionary.

Needless to say, she was a very complex individual. Her acquaintances ranged from the blues people of the jooks and the turpentine camps in the South to the upper-class literati of New York City. She had been Fannie Hurst’s secretary, and Carl Van Vechten had been a friend throughout most of her professional career. These friendships were, for the most part, genuine, even if they do smack somewhat of opportunism on Zora’s part. For it was the Vechten and Nancy Cunard types who exerted a tremendous amount of power over the Harlem literary movement. For this element, and others, Zora appears to have become something of a cultural showcase. They clearly enjoyed her company, and often “repaid” her by bestowing all kinds of favors upon her.

In this connection, one of the most interesting descriptions of her is found in Langston Hughes’s autobiography, The Big Sea: In her youth, she was always getting scholarships and things from wealthy white people, some of whom simply paid her just to sit around and represent the Negro race for them, she did it in such a racy fashion. She was full of side-splitting anecdotes, humorous tales, and tragicomic stories, remembered out of her life in the South as the daughter of a traveling minister of God. She could make you laugh one moment and cry the next. To many of her white friends, no doubt, she was a perfect “darkie,” in the nice meaning they gave the term—that is a naive, childlike, sweet, humorous, and highly colored Negro.

According to Mr. Hughes, she was also an intelligent person, who was clever enough never to allow her college education to alienate her from the folk culture that became the central impulse in her life’s work.

It was in the field of folklore that she did probably her most commendable work. With the possible exception of Sterling Brown, she was the only important writer of the Harlem literary movement to undertake a systematic study of African-American folklore. The movement had as one of its stated goals the reevaluation of African-American history and folk culture. But there appears to have been very little work done in these areas by the Harlen literati. There was, however, a general awareness of the literary possibilities of black folk culture—witness the blues poetry of Langston Hughes and Sterling Brown. But generally speaking, very few writers of the period committed themselves to intensive research and collection of folk materials. This is especially ironic given the particular race consciousness of the twenties and thirties.

Therefore, vital areas of folklorist scholarship went unexplored. What this means, in retrospect, is that the development of a truly original literature would be delayed until black writers came to grips with the cultural ramifications of the African presence in America. Because black literature would have to be, in essence, the most profound, the most intensely human expression of the ethos of a people. This literature would realize its limitless possibilities only after creative writers had come to some kind of understanding of the specific, as well as general ingredients that must enter into the shaping of an African culture in America. In order to do this, it would be necessary to establish some new categories of perception; new ways of seeing a culture that had been caricatured by the white minstrel tradition, made hokey and sentimental by the nineteenth-century local colorists, debased by the dialect poets and finally made a “primitive” aphrodisiac by the new sexualism of the twenties.

And to further complicate matters, the writer would have to grapple with the full range of literary technique and innovation that the English language had produced. Content and integrity of feeling aside, much of the writing of the so-called Harlem renaissance is a pale reflection of outmoded conventional literary technique. Therefore, the Harlem literary movement failed in two essential categories, that of form and that of sensibility. Form relates to the manner in which literary technique is executed, while sensibility, as used here, pertains to the cluster of psychological, emotional and psychic states that have their basis in mythology and folklore. In other words, we are talking about the projection of an ethos through literature; that is, the projection of the characteristic sensibility of a nation, or of a specific sociocultural group.

In terms of the consummate uses of the folk sensibility, the Harlem movement leaves much to be desired. There was really no encounter and subsequent grappling with the visceral elements of the black experience but rather a tendency on the part of many of the movement’s writers to pander to the voguish concerns of the white social circles in which they found themselves.

But Zora’s interest in folklore gave her a slight edge on some of her contemporaries. Her first novel, Jonah's Gourd Vine (1934), is dominated by a gospel-like feeling, but it is somewhat marred by its awkward use of folk dialect. In spite of this problem, she manages to capture, to a great extent, the inner reality of a religious man who is incapable of resisting the enticements of the world of flesh. She had always maintained that the black preacher was essentially a poet, in fact, the only true poet to which the race could lay claim. In a letter to James Weldon Johnson, April 16, 1934, speaking of Jonah's Gourd Vine, she wrote:

I have tried to present a Negro preacher who is neither funny nor an imitation Puritan ram-rod in pants. Just the human being and poet that he must be to succeed in a Negro pulpit. I do not speak of those among us who have been tampered with and consequently have gone Presbyterian or Episcopal. I mean the common run of us who love magnificence, beauty, poetry and color so much that there can never be too much of it.”

The poetic aspect of the black sermon was one of her central concerns at the time of the publication of Jonah’s Gourd Vine; by then she had begun systematically to study and collect Afro-American folklore and was especially interested in isolating those features that indicated a unique sensibility was at work in African-American folk expression. In this connection, she wrote an essay for Nancy Cunard’s anthology, Negro (1934). entitled, “Characteristics of Negro Expression.” A rather lightweight piece really. But it is important, because it does illustrate one central characteristic of African-derived cultures. And that is the principle of “acting things out.” She writes: “Every phase of Negro life is highly dramatized. No matter how joyful or how sad the case there is sufficient poise for drama. Everything is acted out.” She saw the black preacher as the principal dramatic figure in the socioreligious lives of black people.

Commenting to James Weldon Johnson on a New York Times review of Jonah's Gourd Vine, she complains that the reviewer failed to understand how the preacher in her novel “could have so much poetry in him.” In this letter of May 8, 1934. she writes: “When you and I (who seem to be the only ones even among Negroes who recognize the barbaric poetry in their sermons) know there are hundreds of preachers who are equalling that sermon [the one in Jonah's Gourd Vine] weekly. He does not know that merely being a good man is not enough to hold a Negro preacher in an important charge. He must also be an artist. He must be both a poet and an actor of a very high order, and then he must have the voice and figure.”

Her second novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), is clearly her best novel. This work indicates that she had a rather remarkable understanding of a blues aesthetic and its accompanying sensibility. Paraphrasing Ellison’s definition of the blues: this novel confronts the most intimate and brutal aspects of personal catastrophe and renders them lyrically. She is inside of a distinct emotional environment here. This is a passionate, somewhat ironic love story—perhaps a little too rushed in parts—but written with a great deal of sensitivity to character and locale.

It was written in Haiti ‘‘under internal pressure in seven weeks,” and represents a concentrated release of emotional energy that is rather carefully shaped and modulated by Zora’s compassionate understanding of Southern black life styles. Here she gathers together several themes that were used in previous work: the nature of love, the search for personal freedom, the clash between spiritual and material aspiration and, finally, the quest for a more than parochial range of life experience.

The novel has a rather simple framework: Janie, a black woman of great beauty, returns to her home town, and is immediately the subject of vaguely malicious gossip concerning her past and her lover Tea Cake. Janie’s only real friend in the town is an elderly woman called Pheoby. It is to her that Janie tells her deeply poignant story. Under pressure from a strict grandmother, Janie is forced into an unwanted marriage. Her husband is not necessarily a rich man; however, he is resourceful and hard-working. In his particular way, he represents the more oppressive aspects of the rural life. For him, she is essentially a workhorse.

After taking as much as she can, she cuts out with Joe Starks, whose style and demeanor seem to promise freedom from her oppressive situation. She describes him:

It was a citified, stylish dressed man with his hat set at an angle that didn’t belong in these parts. His coat was over his arm, but he didn’t need it to represent his clothes. The shirt with the silk sleeveholders was dazzling enough for the world. He whistled, mopped his face and walked like he knew where he was going. He was a seal-brown color but he acted like Mr. Washburn or somebody like that to Janie. Where would such a man be coming from and where was he going? He didn’t look her way nor no other way except straight ahead, so Janie ran to the pump and jerked the handle hard while she pumped. It made a loud noise and also made her heavy hair fall down. So he stopped and looked hard, and then he asked her for a cool drink of water. (See Zora’s short story, “The Gilded Sixbits,” for another example of the clash between the urban and rural sensibility in Langston Hughes’s The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers, Little, Brown, 1967.)

She later leaves her husband, and takes up with Joe Starks, who is clearly a man with big ideas. He has a little money, people love him and he is an excellent organizer. But Janie does not really occupy a central emotional concern in Joe’s scheme of things. She is merely a reluctant surrogate in his quest for small-town power and prestige. Joe is envied by everyone for having so much organizational and economic ability. But his lovely wife, who represents an essential aspect of his personal achievements, is basically frustrated and unloved. After several years, Joe Starks dies. The marriage itself had died years ago. She had conformed to Joe’s idea of what a woman of influence and prestige should be. But again, she had not been allowed to flower, to experience life on her own terms.

The last third of the novel concerns Janie’s life with Tea Cake, a gambler and itinerant worker. Tea Cake represents the dynamic, unstructured energy of the folk. He introduces her to a wider range of emotional experience. He is rootless, tied to no property save that which he carries with him, and he is not adverse to gambling that away if the opportunity presents itself. But he is warm and sensitive. He teaches her whatever she wants to know about his life and treats her with a great deal of respect. In spite of the implicit hardship of their lives, she has never lived life so fully and with such an expanse of feeling. And here is where Zora introduces her characteristic irony.

While working in the Everglades, they are nearly destroyed by a mean tropical storm. They decide to move to high ground and are forced to make their way across a swollen river. (The storm is described in vivid details that bear interesting allusions to Bessie Smith’s “Backwater Blues.”) A mad dog threatens Janie, and while protecting her Tea Cake is bitten. He contracts rabies, and later is himself so maddened by the infection that he begins to develop dangerous symptoms of paranoia. He threatens to kill Janie, and in self-defense she is forced to kill him. This is the story that she tells Pheoby.

But there is no hint of self-pity here. Just an awesome sense of the utter inability of man to fully order his life comparatively free of outside forces. Zora Neale Hurston was not an especially philosophical person, but she was greatly influenced by the religious outlook of the black church. So that this novel seems often informed by a subtle, though persistent kind of determinism. She has a way of allowing catastrophe to descend upon her characters at precisely the moment when they have achieved some insight into the fundamental nature of their lives. She introduces disruptive forces into essentially harmonious situations. And the moral fiber of her characters is always being tested. Usually, in a contest between the world of flesh and the world of spirit, she has her characters succumb to the flesh.

However, she has no fixed opinions about relationships between men and women. She can bear down bitterly on both of them. She will allow a good woman to succumb to temptation just as quickly as a man. And when such things occur with couples who genuinely love each other, she has a way of illustrating the spiritual redemption that is evident even in moral failure. She is clearly a student of male/female relationships. And when she is not being too “folksy,” she has the ability to penetrate to the core of emotional context in which her characters find themselves. In this regard, she was in advance of many of her “renaissance” contemporaries. There are few novels of the period written with such compassion and love for black people.

In Moses Man of the Mountain (1939), she retells the story of the biblical Moses. Naturally, she attempts to overlay it with a black idiom. She makes Moses a hoodoo man with African-derived magical powers. She is apparently attempting to illustrate a possible parallel between the ancient Hebrew search for a nation and the struggles of black people in America, and she is moderately successful.

The Bible has always been of special importance to her. It was the first book she read seriously. Her father was a preacher. Further, the Bible is the most prominent piece of literature in the homes of most black families, especially in the South. The title of her first novel comes from the Bible. In a letter to Carl Van Vechten, she explains: “You see the Prophet of God sat up under a gourd vine that had grown up in one night. But a cut-worm came along and cut it down. . . . One act of malice and it is withered and gone. The book of a thousand million leaves was closed.” And finally, in further correspondence to Carl Van Vechten, she expresses a desire to write another novel on the Jews, and not necessarily their liberators. She notes, for example, that these “oppressors” forbade the writing of other books. So that in three thousand years, she points out, only twenty-two books of the Bible were written. The novel was never published, but its working title was Under Fire and Cloud.

Her last novel is a sometimes turgid romance entitled Seraph on the Suwanee (1948). Its central characters are white Southerners. It is competently written, but commands no compelling significance. Since she was often in need of money, she may have intended it as a better-than-average potboiler.

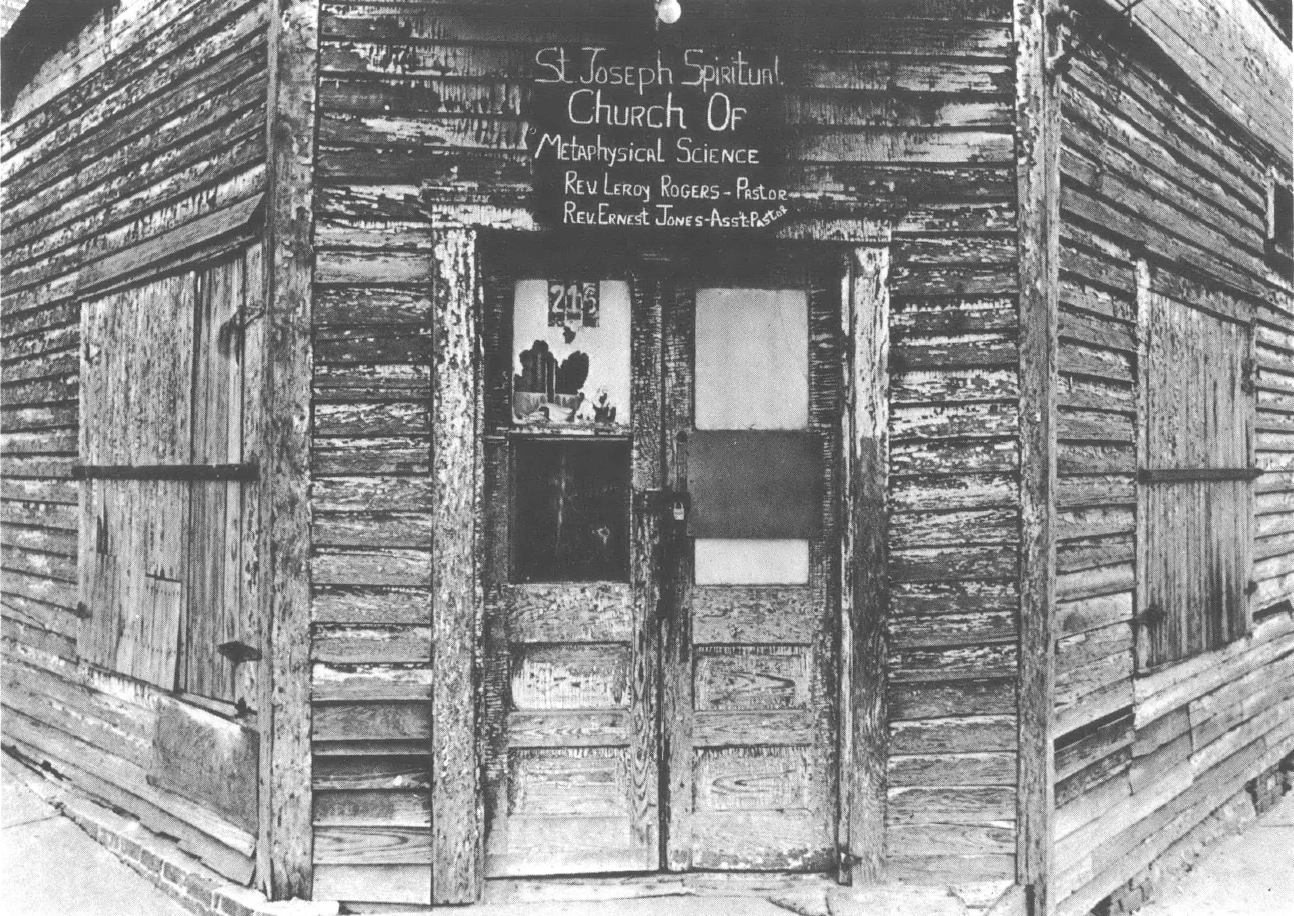

She made her most significant contribution to black literature in the field of folkloristic research. Mules and Men (1935) is a collection of African American folktales; it also gives a rather vivid account of the practice of hoodoo in Louisiana. Tell My Horse (1938), a book about Jamaican and Haitian culture, is perhaps one of the most important accounts of voodoo rites and practices in print anywhere. It successfully competes with most of the books on the subject, and there are quite a few of them. An interesting aspect of both these books, especially Tell My Horse, is the complete manner in which she insinuates herself into whatever kind of sociocultural event she is trying to understand.

Both in Louisiana and Haiti, she allowed herself to be initiated into the various rites to which she had devoted her studies. Therefore, in order to learn the internal workings of these rites, she repeatedly submitted herself to the rigorous demands of the“two-headed” hoodoo doctors of New Orleans and the voodoo hougans of Haiti. She was an excellent observer of the folkloristic and ritualistic process. Further, she approached her subject with the engaged sensibility of the artist; she left the “comprehensive” scientific approach to culture to men like her former teacher, Franz Boas, and to Melville Herskovits. Her approach to folklore research was essentially free-wheeling and activist in style. She would have been very uncomfortable as a scholar committed to “pure research.”

She had learned from experience that the folk collector must in some manner identify with her subject. For her the collector should be a willing participant in the myth-ritual process. Her actions in some of this research seem to indicate that she had nothing against assuming a persona whenever it was necessary. Given the dramatic nature of her personality, it was highly possible; we can be almost certain that she carried off her transformation into ritual participant exceptionally well. Such was not the case when she first began her research while still a student at Barnard College:

My first six months [collecting folk materials] were disappointing. I found out later that it was not because I had no talent for research, but because I did not have the right approach. The glamour of Barnard College was still upon me. I dwelt in Marble Halls. I knew where the material was, all right. But I went about asking, in carefully accented Barnardese, “Pardon me, but do you know any folk-tales or folk-songs?’’ The men and women who had whole treasuries of material just seeping through their pores looked at me and shook their heads. No, they had never heard of anything like that around there. Maybe it was over in the next county. Why didn’t I try over there? I did, and got the self-same answer.

This disappointed her for a while. But soon she discovered exactly how her own background in the South had so thoroughly imbued her with the natural attributes of a good folklore researcher. She remembered that her own Eatonville was rich in oral materials. In a sense, you could say that she realized that she, Zora Neale Hurston, was finally folk herself, in spite of the Guggenheim Award and the degree from Barnard College. Here she is, in Mules and Men, blending into her matierals:

“Ah come to collect some old stories and tales and Ah know y’all know a plenty of 'em and thats why Ah headed straight for home.’’

“What you mean, Zora, them old lies we tell when we’re jus’ sittin’ around here on the store porch doin’ nothin'?’’ asked B. Mosely.

“Yeah those same ones about Ole Massa and colored folks in heaven, and—oh y’all know the kind I mean."

Zora had a way of implicitly assuming that the world-view of her subjects was relatively accurate and justified on its own terms. For example she very rarely, if ever, questions the integrity or abilities of a hougan, or hoodoo doctor. Likewise, she never denigrates her subjects or their rituals, which to the Western mind may smack of savagery. What she sees and experiences, therefore, is what you get. This is particularly true of those cases in which we find her both the narrator and the participant in a ritual experience. Here is another selection from Mules and Men:

I entered the old pink stucco house in Vieux Carre at nine o’clock in the morning with the parcel of needed things. Turner placed the new underwear on the big Altar; prepared the couch with the snake-skin cover upon which I was to lie for three days. With the help of other members of the college of hoodoo doctors called together to initiate me, the snake skins I had brought were made into garments for me to wear. One was coiled into a high headpiece—the crown. One had loops attached to slip on my arms so that it could be worn as a shawl, and the other was made into a girdle for my loins. All places have significance. These garments were placed on the small altar in the corner. The throne of the snake. The Great One was called upon to enter the garments and dwell there.

I was made ready and at three o'clock in the afternoon, naked as I came into the world, I was stretched, face downwards, my navel to the snake-skin cover, and began my three-day search for the spirit that he might accept or reject me according to his will. Three days my body must lie silent and fasting while my spirit went wherever spirits go that seek answers never given to men as men.

I could have no food, but a pitcher of water was placed on a small table at the head of the couch, that my spirit might not waste time in search of water which should be spent in search of the Power-Giver. The spirit must have water, and if none had been provided it would wander in search of it. And evil spirits might attack it as it wandered about dangerous places. If it should be seriously injured, it might never return to me.

For sixty-nine hours I lay there. I had five psychic experiences and awoke at last with no feeling of hunger, only one of exaltation.

Her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, helps to give us a fundamental sense of the emotional tenor of her life. It was a life full of restless energy and movement. It was a somewhat controversial life in many respects, for she was not above commercial popularization of black culture. And many of her contemporaries considered her a pseudofolksy exhibitionist or, worse, a Sol Hurok of black culture. One elderly Harlem writer recalls that she once gave a party to which she invited white and Negro friends. Zora is supposed to have worn a red bandana (Aunt Jemima style), while serving her guests something like collard greens and pig’s feet. The incident may be apocryphal. Many incidents surrounding the lives of famous people are. But the very existence of such tales acts to illustrate something central to a person’s character. Zora was a kind of Pearl Bailey of the literary world. If you can dig the connection.

As we have already stated, she was no political radical. To be more precise, she was something of a conservative in her political outlook. For example, she unquestioningly believed in the efficacy of American democracy, even when that democracy came under very serious critical attack from the white and black Left of the twenties and thirties. Her conservatism was composed of a naive blend of honesty and boldness. She was not above voicing opinions that ran counter to the prevailing thrust of the civil rights movement. For example, she was against the Supreme Court decision of 1954. She felt that the decision implied a lack of competency on the part of black teachers, and hence she saw it as essentially an insult to black people.

After a fairly successful career as a writer, she suddenly drops out of the creative scene after 1948. Why she did this is somewhat of a minor enigma. She was at the apex of her career. Her novel, Seraph on the Suwanee, had received rather favorable reviews, and her letters to Carl Van Vechten indicate that she had a whole host of creative ideas kicking around inside of her.

Perhaps the answer lay in an incident that happened in the fall of 1948. At that time she was indicted on a morals charge. The indictment charged that she had been a party in sexual relationships with two mentally ill boys and an older man. The charge was lodged by the mother of the boys. All of the evidence indicates that it was a false charge; Zora was out of the country at the time of the alleged crime. But several of the Negro newspapers exploded it into a major scandal. Naturally, Zora was hurt. And the incident plunged her into a state of abject despair. She was proud of America and extremely patriotic. She believed that even though there were some obvious faults in the American system of government, they were minimal, or at worst the aberrations of a few sick, unrepresentative, individuals. This incident made her question the essential morality of the American legal system.

In a letter to her friend Carl Van Vechten she wrote: “I care for nothing anymore. My country has failed me utterly. My race has seen fit to destroy me without reason, and with the vilest tools conceived of by man so far. A society, eminently Christian, and supposedly devoted to super decency has gone so far from its announced purpose, not to protect children, but to exploit the gruesome fancies of a pathological case and do this thing to human decency. Please do not forget that thing was not done in the South, but in the so-called liberal North. Where shall I look in the country for justice. ... All that I have tried to do has proved useless. All that I have believed in has failed me. I have resolved to die. It will take me a few days to set my affairs in order, then I will go.”

There was no trial. The charges were dropped. And Zora Neale Hurston ceased to be a creative writer. In the early fifties, she wrote some articles for the Post and the conservative American Legion magazine. She took a job as a maid; and after a story of hers appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, her employers discovered her true background and told all of their friends. Stories later appeared in many newspapers around the country, telling of the successful Negro writer who was now doing housework. One story, in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, quotes her as saying: ‘‘You can use your mind only so long. . . . Then you have to use yours hands. It’s just the natural thing. I was born with a skillet in my hands. Why shouldn’t I do it for somebody else awhile? A writer has to stop writing every now and then and live a little. You know what I mean?” James Lyons, the reporter, goes on to say: ‘‘Miss Hurston believes she is temporarily ‘written out.’ An eighth novel and three short stories are now in the hands of her agents and she feels it would be sensible to ‘shift gears’ for a few months.”

But none of her plans ever materialized. She died penniless on January 28, 1960, in the South she loved so much.

Tags

Larry Neal

Larry Neal, poet-writer, currently teaches at Yale University. He is co-editor with Imau Baraka of Black Fire, and author of Black Bougaloo. He has recently completed a movie script based on Zora Hurston’s Their Eyes Are Watching God. This article originally appeared in Black Review. (1974)