Prophets in Health Care

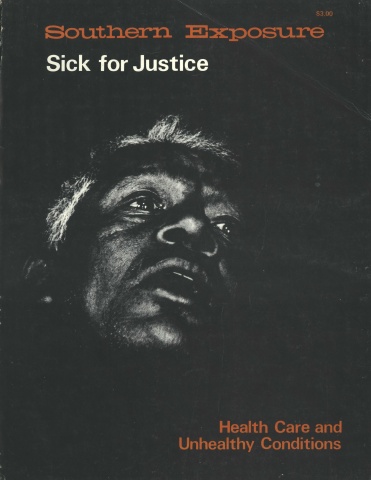

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

Rural Southerners don’t cite statistics on illness and lack of health services, but their everyday experience makes them authorities on the problems brought on by the unequal distribution of wealth, increased specialization by physicians and the proliferation of technology in medical care. Their experience has made them aware that anti-poverty programs, scholarship programs, foundation and government initiatives, and health insurance mechanisms alone will not create the health system they want.

In some cases, however, these programs have encouraged groups in the South to initiate health efforts, especially the construction and operation of health clinics. Some were begun by medical schools, like Mound Bayou, Mississippi; others were supported early by War on Poverty funds, like the Lee County Cooperative Clinic in Marianna, Arkansas. Churches supported the establishment of the Cary Christian Health Center and the Voice of Calvary Cooperative Clinic, both in Mississippi. In some cases, already existing groups like the Federation of Southern Cooperatives of Epes, Alabama, and the South East Alabama Self-Help Association in Lowndes County, Alabama, initiated health programs. Other clinics began because of new community groups, organized with the specific purpose of establishing a clinic; the Mountain Peoples’ Health Councils in east Tennessee are examples of these.

Community efforts at health care are inextricably linked to an American health care system; too often boards, administrators and providers must adjust to each other in a different political setting, one in which community people are invested with decision-making authority. Finally, finances — public and private — are more geared to what physicians charge than to what is needed to promote health. Inevitably, community health efforrs must reconcile themselves with a health system which largely ignores rural and poor people. Consequently, community dreams of twenty-four hour service, emergency care and comprehensive programs including preventive medicine, nutrition, housing, water, testing, education and more, are frustrated by the limitations of the model of American health care, the private physician.

In a national health system that does not know cost containment and where the costs are determined by urban-based, profit-motivated providers, the people most neglected, with the greatest health needs and the fewest resources, are pressured to be the most cost-effective. The community people must deal with health care as a commodity, without a sense of community.

The experiences recounted in these links have presented obstacles to the creation and maintenance of meaningful health services. Invariably community groups require the assistance of health providers and meet initial opposition. Local doctors often view community action as unnecessary or as implicit criticism of their work.

Even when initial opposition gives way to cooperation — or indifference — community groups confront other obstacles. The geographic distribution of professionals adds to the problem of physician shortages. Community clinic profiles all fall within this context, and are related to other facets of health care discussed in this issue. Proposed national health insurance programs, for example — with the exception of the Dellums bill — skirt the central issues of control of medical education and the distribution and nature of services. The case of the UMWA Fund illustrates that even well-established progressive medical programs can revert to the physician-dominated fee-for-service model. Health Systems Agencies may forge another link in the medical-political alliance unless there is representation and effective participation by those who experience first-hand the present inequities in health care.

Efforts to provide care where there was none before and to charge according to the ability to pay were hailed as political models by health activists and overdue justice by the community people involved. In retrospect, these efforts illustrated that justice initiated from below is fragile, and that the economics of equity conflict with a health system motivated by profit. Community control of health resources is an ongoing struggle that is fostered not only by a vision of the future, but by an understanding of changes required in the present as well.

Prophets do not so much tell the future as they make plain the meaning of the events of their own time. In this sense, people who have worked at the community level to achieve health care for underserved communities have much more to tell us than merely the account of their efforts. Their work tells us about everyone’s health system and what we must do to achieve a system of care that is accountable to people.

Tags

Richard Couto

Richard Couto, Pat Sharkey, Paul Elwood, and Laura Green — all affiliated at the time with the Center for Health Services at Vanderbilt University — conducted an extensive evaluation of RCEC for the U.S. Department of Education in 1986. This article is adapted from that report. (1986)