Reading the Hops: Recollections of Lorenzo Piper Davis and the Negro Baseball League

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 5 No. 2, "Long Journey Home: Folklife in the South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

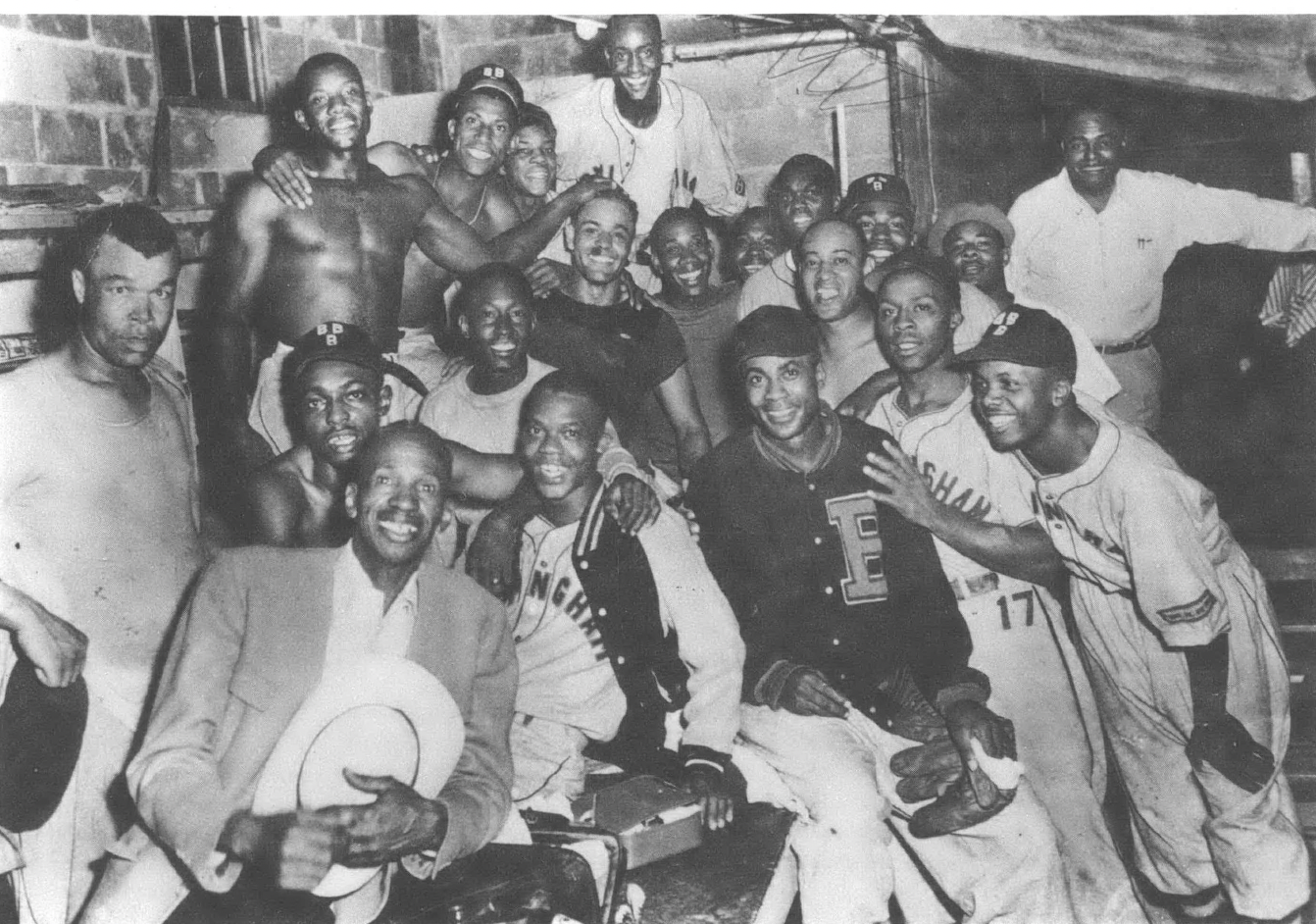

Lorenzo Piper Davis fielded ground balls like a nighthawk seizes grasshoppers. At the plate, he was a feared dutch hitter, a prodigious driver-in of men on base, a constant threat to hit the long ball. In his career with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro Baseball League, Davis starred atp shortstop, second base and first base. He played in numerous all-star games and in three Negro League World Series. He was the League’s most versatile player.

Yet his name is hardly known today even to dose followers of the game. Why? Because he spent his most productive years on all-black teams, playing in cities in front of largely black audiences, or playing "out in the sticks. ” The white press paid little attention to him until Jackie Robinson smashed the color barrier and Major League teams began scrambling for Negro League talent. Davis was the third black ballplayer in modern times to sign a Major League contract. First Robinson, of the Kansas City Monarchs, signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Then Larry Doby, of the Newark Eagles, signed with the Cleveland Indians. Davis, of the Barons, signed with the St. Louis Browns.

But he never made it to the Big Leagues. Perhaps white owners felt he was too old to risk the investment; perhaps it was his bad luck to sign with a dub whose owner wasn’t ready to put a black ballplayer on the field. One thing is certain — Davis had the talent to play.

Davis was born and raised in Piper, Alabama, a coal town southwest of Birmingham. At fourteen, he became the youngest player on Piper’s “first nine. ’’ He was so far advanced from boys his own age that, playing street ball, he had to catch for both sides because they wouldn’t let him hit. After high school, in 1936, he went on the road with a barnstorming Negro team, the Omaha Tigers. With the Tigers, and two years later with a team from Yakima, Washington, he traveled all over the West and Midwest, playing local white dubs and black dubs, and catching the eye of rivals who wanted him to play with them.

Traveling was too expensive, too wearying, for the small and uncertain pay. So Davis came back to Birmingham, got a job with the American Cast Iron Pipe Company (Acipco), and played on Acipco’s black baseball team in the City Industrial League. He stayed with Acipco from 1939 until 1943, when the Barons tempted him away. Negro ball at that time regularly outdrew white minor league ball in Birmingham by several thousand fans per game. When the Kansas City Monarchs came to town, you might go to Rick wood Field and catch a glimpse of Satchel Paige’s fastball. Or when the Homestead Grays came, you might try to follow the flight of a Josh Gibson home run.

Piper Davis became manager of the Black Barons in 1948. He continued to play every day, and he led the team into its last world series. The Negro League was waning, its best young players snapped up by Major League organizations, its fans lured by the spectacle of the black man competing in white ball. Amalgamation of white and Negro baseball killed the Negro League while it enriched the white-owned and -operated Major League.

In 1950, Davis got a shot to play with the Boston Red Sox. His earlier option with St. Louis did not pan out. This time he seemed a sure bet. But the dream chance ended with an implausible rejection. He began the season with Scranton, a Red Sox farm team in the Eastern League. He was leading the dub in nearly every offensive department when, in the middle of May, the Red Sox cut him.

In 1951, Davis went out to play with Oakland in the Pacific Coast League (PCL), a minor league of the Major Leagues — white ball. He stayed six years in the PCL, then finished out his playing career in the Texas League, with Fort Worth. He returned to Birmingham in 1959 to manage a new Black Barons team in a realigned Negro League. The season ended shortly after it began; there simply was no market for Negro ball.

I grew up hearing that the old Negro teams were made up of downs; not that the players didn’t know how to play the game, but that they weren’t serious about it. They were entertainers, mimics, Negroes. A black ballplayer was a Negro before he was a ballplayer. A white ballplayer was just a ballplayer.

My own experience flew in the face of this prejudice. We lived in earshot of old Ebbets Field, where the graduates of the Negro League first worked their baseball magic with the Dodgers. Could anybody say that Jackie Robinson took baseball lightly? Or that Joe Black and Roy Campanella gave the game anything less than their total effort? These were solemn ballplayers, determined to prove they could play, and playing to the best of enormous abilities.

Everyone could see this. Still, the myth of Negro downing persisted in white circles. Major League baseball did not get around to placing former great Negro ballplayers in the Baseball Hall of Fame until eight years ago. In seven years — the committee to nominate former Negro ballplayers expired last year — only nine players were chosen.

The performance of black ballplayers in the Major Leagues came as no surprise to blacks. “We felt we could play, ” says Piper Davis. Black ballplayers did not suddenly become skillful, clever, or gentlemanly upon entering white ball. They brought with them a style of play developed in Negro baseball. It began on country fields and on the sandlots of Southern towns and cities; gained experience in the industrial leagues of manufacturing centers; and matured in a self-regulated Negro League.

Whites claimed that Negro ball “was not organized ball, ” says Davis. His recollections reveal intense organization — though not in white terms of contracts and statistics. For example, transportation of the team from town to town had to be carefully arranged. You were black, so you knew in advance where you were going to sleep, eat and use the toilet, or you might find yourself out in the cold. The bus driver was the most valuable man on the dub; he kept you rolling, he kept you safe.

Davis had a window on America, traveling with Negro ball. He observed everywhere the place of baseball in the local life. His history of baseball in Birmingham is a history of Birmingham told through baseball. Hearing it, then reading it, I perceived the awful exclusion felt by people wanting to partake of the national culture and blocked from doing it.

Piper Davis’ recollections are taken from ten hours of taped interviews and notes. I visited Davis in Birmingham this past July, where he lives with his wife on the west side of town. Each of three interviews began sedately enough in the living room of the Davis home. After about an hour of feeling strapped in the chair, Piper would rise and take position near second base, bending slightly at the knees and balancing on the balls of his feet, pendulum arms making a small arc between his knees. Anticipating the pitch, he was gone at the crack of the bat to cover the bag — on the living room side of the dining room table. Planting his right foot, mashing the carpet, he relayed the ball to first, completing the double play. No one can tell me he can’t make the play today, at 60, as well or better than the average Major League second baseman.

This was a meeting of a player and a fan. Yet, Davis was exceedingly modest about himself. He was eager to tell his story, and the record he wanted to give was an appreciation of the men he played ball with. In editing these recollections, / have left out much material about Davis’ winters playing basketball with the Harlem Globetrotters. Piper Davis, the long and lean infield star of the Negro Baseball League, could also drive to the hoop with the best of them. But baseball was his first love.

(Editors’ note: What follows are excerpts from the longer interview. Apologies are extended if any of the ballplayers’ names are misspelled; every effort was made for accuracy, but because few Negro League members are listed in baseball source books, there remains a possibility that a name has been transcribed incorrectly.)

School ball, we didn’t have a high school; they had a high school, we didn’t. And the black school, the school children would consist of two towns, Piper and Kolina, which was both owned by the Little Cahaba Coal Company. Our baseball team in elementary school would play about four games, or five, during a season, against other black schools — West Blocton, Marvel, Montevallo.

One year they had a coach at the white high school who arranged for our team to play against theirs. Of course, some of em had a little age on us because they was up to the twelfth grade. Our catcher was a boy named Eugene Latham. He was our best hitter, our biggest man. But he wouldn’t go up to the white diamond to play in the game. He was afraid of white people — he’d always been afraid of white people. So we lost the game.

My father was in the coal mine but he heard about it while we were playing. The trip rider would come out of the mine, and he went back down and spread the news, that the blacks was playing up on the white diamond. My daddy got home and told me he heard about we all on the white diamond.

“You better stay away from up there.’’

I told him, “They coming over to play us next week.”

A home-and-home arrangement. And when they came to play us on our diamond, we beat em because our catcher would play then. We beat em on our diamond.

And after that, they got rid of that coach next season. A little bit too friendly with the blacks. At that time they called em colored, Negroes, nigras — see, he was white, he was at the white high school, and he even come over to our school and showed us how to mark off a basketball court; brought the rule book and everything.

I was born in Piper. My daddy worked in the coal mine all his life. Piper is about forty miles from here — Birmingham. They dig coal down there now from the top; it won’t hardly be on the map. All that area is coal mines. You see this big mountain right here on the south side, that’s ore right there. And when you get below Bessemer, it turns from ore into coal veins, and it runs all the way down. Used to have a row of little cities — not cities, we would call them camps, mining camps. Right in there you had Helena — Helena’s still going — and Dogwood, Blocton, Marvel, Kolina, and Piper. Piper was the tail end.

All the mining camps had baseball teams. Piper and Kolina teams were united for a long time. We had what we called the first nine — that was the men, boys from nineteen, twenty, up. The second nine was boys from about fourteen up to eighteen. I was the star player on the second nine, but I’m the batboy for the first nine. So, one Saturday they were playing. And I’m the batboy in these overalls — that’s all we could afford in those days. I was the batboy in overalls and the first baseman got hurt. They wanted to bring an outfielder in to first base and put a pitcher in the outfield that could hit pretty good. Now there was a fellow that was overseer; he would collect money to get the balls and bats, but he wouldn’t have anything to do with the managing part of it. They were around there discussing it, and he said, “Put that little old boy over there you got. He can play just as good as the boy you say you going to put in.”

So they put me over there. I was about fourteen then. I’ve played first nine ever since.

My daddy was a coal miner his whole life, forty-some-odd years. He worked five days a week, but during the Depression he would work two days sometimes, and then when it would start rolling, he’d have to work late — long shifts. I’ve seen him lay down — you see, they changed clothes at home, didn’t have a bath-house. He’d get home about two-thirty or three o’clock, take a bath behind the stove in the kitchen and just lay down there and sleep and go right back to work — he would only be there for just a short while. He had to get up about five o’clock to eat breakfast and walk to work.

My daddy played the guitar for the Saturday night fish fries. He played — and my mother was very religious; every Sunday she would ask somebody to go to church with her. She kept on, every Sunday morning she’d get up and she’d say, “Are you going to church with me this morning?”

And he’d say, “Naw —”

He played all Saturday night. So finally one morning, one Sunday morning, she asked him, “You going to church with me this morning?”

He said, “I believe so.”

He went to church with her and he came back and gave his guitar away. Didn’t play it anymore. I was a baby then, because when I got up some size to know anything he was going to church.

I had rules on me — I had to have the water in. The hydrant was in front of our house. I better have all the buckets full before I go to bed. The water I’d bring in would be enough so my daddy could take his bath. We had two buckets and a kettle — I had to keep those two buckets with water. And when he come in, I’d have em full.

I had to be home when my daddy come up out of that hill. The way he came home from the mine he had to walk a little incline. Sometimes I’d be playing over on the other side of the camp. We didn’t have streets as such, we just had rows, a hill, and like that. “Up on the hill,” or “down in the valley.” Had a row of houses started from a flat and went down in the valley to a branch. We’d call that, “down in the valley.” “Where you going?” “I’m going down in the valley to old Jim’s house.” Or, “I’m going on the L, I’m going in Number One quarters.” They had a area over there flat like it was in front of our house; you could play catch and play stickball and stuff. I be over there playing but I’m watching. And when Papa come out of there, over the rise, I get my little balls and bats and go on with him home.

He didn’t fuss at me too much about the time because he knew I’d be home if I could get away from where I was. My mother did all the fussing and spanking. I don’t think my daddy ever put his hand on me. One time — I had to be home at five o’clock. Our house was about the fifth black house before you go out of the community. On the edge of the community, the timber truck people would live. They were white, people that hauled timber for the mines. Had three or four white houses, families, on that end of town. Closer to the woods, the most woods. You go the other way, you going to Kolina, Blocton, Marvel, and all like that, north of us. And you couldn’t go across the river because the company didn’t own that land across the river.

So one day the cotton picking truck came in from the country. He got to pass our house first, picking up cotton pickers. Then he went all in the L, in the bottom, picking up people to go pick cotton. I didn’t want to go and pick no cotton. And my mother wasn’t there noway. But when the truck came back going out of the camp, one of my buddies was up there. I asked him, “What time you coming back?”

He said, “Five o’clock.”

So I ran and caught the truck. Went out there and picked cotton all day. I think I made thirty-some cents. When the man picked my cotton out he said, “Yours is too dirty.”

I just picked up everything that I saw. That sun was going down, too; I knew it was around five o’clock then. When I got home they were eating. And I was supposed to be home when Papa come home. When I come inside that door, Mama met me. She had a strap, which my daddy would whup his razor on. That’s what she had. She let into me with that thing— she didn’t ask no questions what happened or nothing. She ain’t taking no answer because there’s no answer I could give her, I’m still walking and I wasn’t there at five o’clock. Was no answer to give. She wore me out, she knocked me down ducking and dodging, and I fell down. Papa grabbed her, “Georgia, you going to kill that boy.”

And that’s the last whipping I got.

I would lay in bed and listen to ball games. Bull Connor — you heard of Bull Connor — well, he used to announce games for the Birmingham White Barons — because the black team was Black Barons. Southern Association club, minor league of the major league, all white. And he would announce at Chattanooga, Memphis — Chattanooga Lookout, Memphis Chicks, New Orleans Pelicans, Little Rock Travellers. They had eight teams in that league — Nashville — I forget Nashville’s nickname — Knoxville Smokies. I knew em all.

I would listen to them on the radio. And when I left there and come up to Fairfield, I could get a Pittsburgh Courier then. The black paper. I’d get one every once in a while and I’d read about the black teams playing here in Birmingham. We used to take the Birmingham News — and they used to have a Blue Monday here, a lot of places be closed. In Birmingham the black ball club would play a lot on Blue Monday out at Rickwood Field. I’d get a chance to read about it in the paper.

Then I found out that the black teams from the North that was in the Negro League — like the Homestead Grays who was playing out of Pittsburgh — well, they was playing down this way because they had a lot of ballplayers from this area. The Philadelphia Stars trained in Mississippi. They come down here and maybe throw the ball three or four days; they would start about Tuesday or Wednesday, and play an exhibition game that Sunday. So the Homestead Grays would come down to Alabama, and the New York Cubans, northern teams from the Negro League, and they come down here in the spring of the year. Some of em would, and some of em would stop in Virginia.

The New York Cubans would have about seven or eight Cubans and the rest black Americans. They’d play winter ball and just come over to Miami. Dihigo, Vargas.

When they first come over here Cubans didn’t want to be black. They didn’t want to be recognized as black — and you couldn’t blame them. Because in their hometowns they were Cubans; or they were Puerto Ricans, Panamanians. You didn’t read in the paper about no black Cubans, no colored Cubans. They was all Cubans.

So these teams would come into the South to find their ballplayers — Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama. The only towns that really had teams in the Negro Leagues was Birmingham and Memphis, in the South. Now Atlanta had a good ball club, New Orleans had a good ball club, but they was traveling teams. In the Negro Leagues at that time was Memphis, Birmingham, Indianapolis Clowns, Kansas City Monarchs, Chicago American Giants and the Cleveland Buckeyes. They were in the American division. New York Black Yankees, New York Cubans, Newark Eagles, Philadelphia Stars, Baltimore Elite Giants, Washington Grays that used to be the Homestead Grays — they was in the National division.

You take the Homestead Grays at the time Luke Easter was playing. Easter was from Mississippi; Buck Leonard was from South Carolina; Howard Easterling was from Louisiana; and the Bankheads, Sam and Dan, from right here at Cordova. Their second baseman, he was from right down here at Bessemer.

I went to the ninth grade in Piper, and the year before I left they raised it to the tenth. I left there in 1933 to come up to Fairfield and go to high school. My mother had four brothers there, and they worked in the steel mill. On my mother’s side they had enough boys to have a baseball team. They had a baseball team, in the country, my mother’s brothers. There’s twenty-four children in all, and she’s the baby girl of the first group. The second group, some of em is just as old as I am. Her mother died in childbirth with one below her.

They had enough to have a baseball team, and they had a diamond on their place. This was down — they call it Antioch now. It’s about eight miles due east of Centerville. It’s family property, and I take care of it now. I rent it out every year.

In high school, Fairfield, they begun calling me Piper. They used to call me Piper-Kolina, then they shortened it to Piper. Everybody calls me Piper, and always has since.

I wrote to the Philadelphia Stars for a tryout. I was finished with the twelfth grade then. And they wrote me back a letter for me to pay my way to wherever they were in Mississippi. And if I made the club they would reimburse me. So my daddy told me, “No, if you good enough to sign, if they want you, they’ll come here and get you.” He was very strict. Because when I started playing with Kolina, he told the man, “If you want him to play with you, you come and get him and carry him up there and bring him back to this house or see that he comes back to this house with a confidential man.”

He was looking out for my conduct — didn’t want me to get away.

My daddy said, “If they want you on those terms you don’t go.”

So I was at home one Monday morning. We would have mission meetings, our church would, and my mother would go to mission meetings on Monday morning. I was around the house and here come a car down the road and they all got out. It was about five or six ballplayers. One was from here, one or two from Blocton, one or two from Marvel. They came over to my house. A fellow from Omaha was getting up a club, and he heard that he could get a lot of ballplayers out of the Birmingham area. He had come here, and they told him that I was at home. My mother, when she came in, I was packing my bag to go. And I knew where they kept the money — in a little bag, a money envelope, and stuck it up in the pantry. I got me ten dollars out of there. And she came in — I was packing her bag — and she said, “What is all this?”

I introduced her to the fellas, and she said, “What are you going to do” — she called me “Baby.”

I said, “I’m going to play ball with these fellas.”

She said, “Well, how far are you going? Where is it?”

I said, “Omaha.”

She said, “How far is that from here?”

One of the fellas said, “About eight or nine hundred miles or more.”

At that time, railway travel was cheap. I said, “I already got ten dollars out of the envelope.” She said, “I don’t think that’s enough.”

So she went in and got another ten dollars and gave it to me and said, “You always keep your train fare back home.”

I said, “I sure will.”

They came to my door and got me. My daddy had halfway given me his permission in just talk. He said, “You can go....” He never did want me to work in the mines. I worked in the mines a little — but when I finished high school, the mines was on strike. And I went to Alabama State College — it’s Alabama State University now — in Montgomery, and he borrowed the money for me to go to college. I had a part scholarship for basketball, but that wasn’t enough. So he borrowed the money for me to go to college. Come time for the next tuition, they was still on strike, and I knew he would have to borrow the money from the company. So I sneaked away from college in the middle of my first year, because I knew he would have to borrow the money for me to finish the term, and that would put him then maybe three or four hundred dollars behind.

So I came back. I wasn’t doing anything. But I always wanted to make my own money. My daddy would give me the change out of his envelope every two weeks. Sometimes, if it was under thirty-five or forty cents, he would make it out fifty cents, or sixty cents.

So I told him to get me a job in the mine. He didn’t want to get me in the mine but I kept on until he started me in the mine with him. That was the tail end of 1935 and the first part of 1936. My stay in the mines didn’t last too long because I was afraid of em. We had four incidents — accidents in the mine. We were working in Number Two while they were cleaning Number One and a guy got hurt real bad. Had black boys for trip riders — they rode a trip. See, the miners would leave the top in cars and ride down to a certain point. Then they would all get out and walk to certain areas — they have guys digging coal in what they call a room, a cut-off, and they have guys digging straight ahead on the line what they let you down on. A coal vein runs on an angle. When they carry the coal, they got a motor up at the top end that pulls these cars up that come out from those rooms. And they got a man up there in a little old shack that pulls em up — he just sitting down on a stool, with an electric motor pulling up the cars.

Well, my little girlfriend that I was liking then, her brother worked in the mines at night, and he rode that trip up with them cars. He’d hook those cars up that the drivers would have pulled out from the rooms with a mule - they let mules down in the mine. And these rooms was just cut out of the wall of the mine. They about forty feet apart, and they go up so far till the coal gives out and you get back into rock. The room I was in with my daddy, when I went in that room I could stand with a three-foot shovel on the top of my head and I couldn’t touch the top; but on the other end I was on my knees shoveling coal over here to my daddy, so my daddy could load it in the car.

So my girlfriend’s brother rode the trip that night. When he’d pick up the last car, he’d load it down behind what they called a door — it’s just a big curtain to turn the air in certain directions. He’d signal the guy on top — had two wires and he’d bring the wires together — “Peep” “Peep” — one for stop, two for slowdown, three to go, whatever they had; and stop the trip and get off and open that door so the cars can come through. And he’s got his light shining to see how far he wants the cars to go. He stepped in the empty line — and they jumped the switch and come on his side and tore him up.

Jeremiah Nelson, he was a pitcher.

We went to work next morning, me and another fellow - we used to play ball together — would walk to work together, and his daddy and my daddy would walk together if the time was just right. And this fellow said, “You hear about Jeremiah getting killed last night?”

I said, “Noooo!”

We passed by the house and they had a light on. The guy next door came out and told us, “You hear about Jeremiah getting killed last night?”

Told him, “Yeaaaah!”

I went on to work. See, I would go up to the lamphouse and get my daddy’s and my lamp. And I’m walking along that morning with a fellow’s lamp that came home with Jeremiah and didn’t tell us anything about it. I’m carrying his lamp back to the lamphouse, got it in my hand. I told the lamphouseman, “Here’s Sam’s light.”

He said, “Put it on charge. He had to carry it home because he took Jeremiah home last night.”

I said, “Just give me my daddy’s because I don’t want mine, I don’t want my light. I’m finished."

I carried my daddy’s light down to him in the car. All the drivers was on top anyway. They were getting ready to strike because they wanted a man to sit down in the mine and open that door. The mules had gone on into the mine, and the drivers sitting out on top. They went down about thirty minutes ahead of us because they walked down. So they sent for the superintendent. He came down in his pajama top, houseshoes. And his favorite word was, “No twenty-seven ways about it. I’m not going to hire one man to sit on his ass out there and just open that door.”

I saw the drivers pouring their water out. I said, “Look like you coming home, too, Papa. I’m gone.”

I went home and taken my bath when he got there, and I went down to the pay office and I told the man I wanted my time. He said, “I can’t give you your time just like that. I got to have a reason.”

I said, “Just put on there, ‘Afraid of mines.’”

He said, “That’s a good enough reason.”

Signed my first contract with Omaha for $91 a month. We would travel out of Omaha — we trained in Memphis, we played one exhibition game against the Memphis Red Sox. They were in the Negro American League. But the Omaha Tigers was a traveling ball club.

Omaha had some ballplayers that went to the Homestead Grays, from off the club. Some of the local teams we played was farm clubs to the Negro League clubs. The little old club in Knoxville was the Memphis farm club. The ballplayers that didn’t make the Memphis club, they sent em to Knoxville — let the man there have em, he paid em, contract wasn’t such that he owned em or nothing like that, he just sent em over there so they could play.

When we trained in Memphis, I’m looking at the ballclub, and the ballplayers that didn’t come with us on the road. The man asks me, what position did I want to play. I knew I couldn’t beat the catcher because he played down there at Marvel, Alabama. I’m looking at the other positions — the shortstop was pretty good. I was a little lanky too. I said, “Well, I’ll play outfield and I’ll be a utility catcher”— because I used to catch a little in high school.

One Sunday during training, Memphis was playing the Monroe (Louisiana) Monarchs a exhibition game. And our shortstop was from that area. When they checked in the hotel where we were, he was there, and they borrowed him to play with them because they wanted to make a good showing. Monday morning he was sick. He made enough money to get drunk, and he was sick Monday morning, couldn’t go to practice. Everybody else showed up for practice, the outfielders and whatnot, and I stayed in the outfield. But the next day the kid was worse. So the manager came to me and said, “Hey, kid, look like I’m going to have to bring you to the infield.” He saw how I was catching the ball in the outfield. “Look like I’m going to have to bring you to the infield because this boy is in bad shape.”

We split with Memphis that next Sunday, and we left out of there Sunday night going to Omaha. The boy that was sick, well, as things are now I can say it was similar to cancer, because he had a bad throat irritation. We put him on the back seat of the bus, and when we got to Omaha that Tuesday evening, they called a doctor and the doctor came and sent him to the hospital. I think he lived about four days, and he died. I finished the season at shortstop.

I was eighteen years old when I left on the road traveling with the Omaha Tigers. Too much traveling and not enough money. Besides, they didn’t finish paying us what little we were supposed to get. We just traveled, traveled. Started in from Omaha, played on up to North Dakota, then went on across almost to Spokane, then we came on back down through Idaho, Kansas, and places like that. Played white teams along the way, played black teams. Barnstorming with local clubs.

So I left Omaha and I come back to Fairfield, where I had finished high school. I got me a job at the tin mill, when they was building the tin mill out there. Fairfield had a baseball team — that was a TCI (Tennessee Coal and Iron Company League) team. TCI had two divisions; had the manufacturing division and then they had the mine division, ore division.

O, man, you used to have some teams around then, had some teams! Stockham had a club, Acipco had a club they was rivals. Schloss Furnace, Westfield Sheetmill, Perfection Mattress, Ensley — was in the manufacturing division. Winona, Edgewater, they was in the ore division, mining division. TCI used to own all that, which is US Steel now.

You find an industrial league in Atlanta, but not as many teams as you got in Birmingham. But they had ball clubs and they had a league. They had a league in Memphis, an industrial league. But baseball teams wasn’t as prevalent there — because this is a manufacturing town, and that’s why it’s so much baseball.

Our job played out because we almost got the building up. But they took my name to come back, in the shop. At that time a boy called me from Montevallo, one of the boys I played with in ’36. And he asked me, did I want to travel at baseball again? I got laid off right after Christmas, the week after Christmas, and he called me. He called me, said, “There’s a team from Yakima, Washington, and I got a letter — the man going to be here—”

I played with Yakima that year. They give me a contract — had a contract with all of em. They all give you a piece of paper to sign, a contract, which wasn’t valid.

We played local clubs all up through the West, and sometimes we would hook up with another traveling club. We met the House of David — they played for a church out of St. Joe, Michigan, I think it was. They wore long beards — church team. We traveled with them a week or two.

But mostly it was local clubs. All towns, the big towns especially had a good baseball team and they would go to the semi-pro tournament in Wichita. That’s the teams we would play. Well, we played the Lewiston, Idaho, club and they won the right to come to Wichita. And we were playing in Wichita a week or so before the tournament’s supposed to start. And the Wichita team wanted me to play with them. I was there signing up, and Lewiston kicked. Lewiston had played them a exhibition game a day or so before the tournament and they kicked. They said I hadn’t played enough games. So I couldn’t play, they rejected me. So I caught up with our team again, and we were working ourselves on back to St. Louis. And a kid that started with us that year, name of Howard Easterling — now he was a good ballplayer — he left us because we weren’t making any money. I left Yakima, too, when we came to St. Louis. I wasn’t making that trip back to Yakima — we had come off of salary on percentage — and when we got to St. Louis, I said, “This is far enough for me.”

There’s so many ballplayers that played and got mad with baseball and quit because they couldn’t make any money. Good ballplayers, but they couldn’t make a living at it.

Come back home in ’38 and got married — we’ve been together ever since. And I got my job at Acipco, A-C-l-P-C-O, straight out on Sixteenth Street, manufacturing plant, makes pipe, cast-iron pipe. It’s short for American Cast Iron Pipe Company. I had broke my leg playing at Westfield, and I went to Piper to stay because I didn’t want no expenses on me. So I went to my mother’s to stay. And one of the fellows that worked up here at Westfield got me on. He told me they was going to hire that day. I asked the man, “Can I go up in the shop and get Censel Upshaw?”

He said, “Yeah.”

So I went up and got Censel. He couldn’t come out of the shop but he come to the back part, the employment place, and he knocked on the window and pointed the guy to me and said, “Baseball player.”

That was enough for them. He call me up and I go on around the front and I get a job. But I had to work under my daddy’s name, John Willy Davis, because I was a minor and they wasn’t supposed to hire you under twenty-one.

After my leg healed — I was taking batting practice with the boys, and I was the scorekeeper, with my crutches. I came back at the tail end of the season. And we were playing Acipco, an exhibition game; they wasn’t in our division. I was walking now, hopping, I’d thrown away my crutches a couple of weeks. I was getting ready to play.

Our manager asked their manager, “If I stand him on first base will the guys run over him?” — Negro ball was rough then.

He said, “No, we got a nice bunch of fellows.”

First time up, I hit one in the road — in front of a schoolhouse — drove in one or two runs; next time up, I hit one in the school yard; and the next time up, I hit one up against the tennis court, in right center. So we had enough runs and they took me out of the game. The manager for Acipco, he eased around to me and said, “If you ever want a job, call me.”

So, I didn’t want to go out on the road again, and I was married — so I called him up. He said, “Yeah, come on out here tomorrow.”

See, your better ballplayers were right here working, that had experienced the road a little bit. I played at Acipco with Artie Wilson, Ed Steele, guys that played later years in the Negro League. Powell, too, and Herman Bell, the catcher. We were on Acipco ball club. That’s five Black Barons right there on the same company team.

My first season with Acipco was ’39, but I started working there in the winter of ’38. I stayed there until April of ’43. I played four seasons with the club. See, the companies would sponsor teams for the amusement of the fans, and to have a baseball team competitive in name, what company could have the best team. They’d buy you everything — balls, bats, uniforms. They give you a trip and pay all your traveling; didn’t have to worry, insurance and everything was paid for. Baseball players had two lockers, baseball equipment in one locker and work clothes, dress clothes, in the other one. It was a better deal than signing with a traveling club. That’s why I stayed.

Acipco had a white team, too. All the companies that had a black team, they had a white team. Acipco’s little second baseman, he rode — we called it the dinky; little old electric car come around and pick up special stuff - he drove that. And we got to talking one day. I said, “Look, if they would just lock us up in the field, don’t have no spectators to harass anybody, we’d run you to death. We’d run you to death.”

“O, noooo, O, noooo, O, noooo.”

I’d played against white boys and I saw their type of ball. All the white boys that would play with Acipco, they wasn’t good enough to make organized ball. Of course, a lot of ern, the family wouldn’t allow em to go off for just that little money — now this is the white part.

So, he said, “O, noooo.”

And I said, “We’d run you to death.”

And one of the boys was from my home town, Piper, Alabama, white boy.

We never played em. But one day a couple of weeks later, I saw em standing out there in the trees way down in left field below the stands. Out there peeping, three of em. We played Monday, Wednesday and Saturday. They played Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. And the day they were out there, Steele hit a couple of balls in the dump — it was a lime hole then, but they dumping in it now to fill it up. Come back a day or so later, the little second baseman came riding down on his little electric car.

He said, “Hello.”

I said, “What’d you think? I saw you out there in that tree.”

He said, “I don’t know. It’d be a good battle.”

I said, “We’d run you to death” — because Herman Bell had been on the road traveling. I had been on the road traveling with baseball.

My daddy didn’t see me play ball until I came back here, started working with Acipco. I was on the road two years, and of course, he couldn’t. And when I was at home, he wouldn’t go to see no ball games in Piper and Kolina. He never did, my mother either. But she came to a ball game in Fairfield when my half-brother pitched against us.

My daddy came to see me play, I was at Acipco, first time he seen me play. And my boy was at the game that day. Of course, he had seen me play before. I hit a home run that day. My boy was small, he was young, and he came to see me play. And I slid into one of the bases. Well, we’d have to go to the shop and take a shower, change clothes. And they got home before me. When I got there, my boy was hanging on the gate. And in the living room we had one of these old coal stoves, it was built up on legs about six inches high. My boy caught me by the hand, we went on in the house, and he just talking at me: “Hey daddy, hey daddy, here were you slide, here were you slide—”

He flew across the floor and hit the linoleum and slid up under the heater. I had to pick the heater up so my wife could pull him out from under there, because I didn’t want to pull him out slow and tear him up. So she pulled him out from under the heater.

“Here were you slide, here were you slide.”

My daughter was one of my favorite fans. She’d clap — and years later, one Sunday in particular, I was at bat, crucial time, and most of the fans knew that I was a clutch hitter; and she jumped up and shouted and a little clap she’d make — clap-clap-clap-clap-clap-clap — she said, “C’mon, daddy, c’mon, daddy.”

And I missed the ball by a foot. I could hear distinctly out of the stands, “I wonder what’s wrong with my daddy.”

When I left Acipco in 1943, I was making $3.36 a day, five days, no money for playing baseball. They just give you time off; you got off about one-thirty. But before I left they dropped it to three o’clock. A lot of fellas was getting cars then, and things was getting - that’s when they started getting a little rough and a little tight. They wasn’t giving the black man as much as they had been. Because when I went there in ’39, we got off at one-thirty—they used to get off at twelve-thirty, used to get off at lunch and didn’t go back. Then they dropped it to one-thirty. The next year they lowered it to two-thirty. And the next year they dropped it to when you got off. A lot of sponsors stopped having clubs altogether. I don’t know what brought on the change, really, but it was happening before the war and at the beginning of the war.

When I went to Acipco, they would have a picnic for their employees every Labor Day. We only had one, and they cut it out. And they used to give turkeys and things for Christmas - the year I got there they cut that out. Used to give every employee a turkey and bag of groceries for Christmas — and they gave you five or ten dollars, then a dollar for every year that you were there. So I wasn’t there — I went there in October or November, so I didn’t get but five dollars, or less than that.

Perfection Mattress, making mattresses, they cut out their club. They cut down the league to about six teams, eight teams. Then they started — say a guy would sell barbecue or something like that at the ballpark; then he would do most of the sponsoring. Then the teams, the hometown fans would chip in a bit and take up a collection at the ballpark.

Acipco cut their team out altogether after I left there. Two or three cut their teams out because of integration. Stockham’s team almost went because of integration. The company felt they might have a little trouble, wouldn’t get enough men to have a good club, enough whites who would play with blacks. Integration come out into the open and whites didn’t want to play. You take a place like Hayes Aircraft. They had two clubs, and the year they said they’d integrate, the whites didn’t have no club, they had black. Then the company kicked because they was sponsoring just the black employees. So they dropped the team.

They had to integrate, anybody, any of em that had government contracts. This was right before King made his movement, right at the top of it. This was after the war, in the ’50s; but they started cutting back before the war.

We had more crowds at our games — because that’s all people had to do then. You go out to the ballpark now, the two biggest rivals is Connor Steel and Stockham, Stockham Valve and Fitting. Used to be Acipco and Stockham. Stockham makes fittings for all type valves, and all sizes. But Acipco makes the pipe. Well, you go out there today it won’t be three hundred people out there to see a ballgame. In my day, if we played Stockham, when we got to the ballpark, before hitting practice, the stands would be full. There would be standing room only after that. Gametime — folks would leave from around here — of course, they didn’t live here then, lived on Center Street and that way on, down in the valley. White lived all up here then. You better not be caught up on this hill after six o’clock, they’d put you in jail for prowling or something like that. Call the police and they’d chase you home.

In ’41, had a manager of the Birmingham Black Barons named Candy Jim Taylor. He come out to Acipco, we were playing one day, and they were here. He said, “C’mon, boy, and play for me.”

I said, “What you paying, Uncle Jim?”

He said, “About a hundred fifty, a hundred seventy-five a month.”

I said, “O, noooo, noooo, no way.”

So, in 1942, a fellow by the name of Winfield Welch came here as manager of the Black Barons. He was manager of the Harlem Globetrotters, too. Well, I played some exhibition games with the Barons. He gave me five dollars a game — and I was making $3.32 at Acipco per day. And at Acipco we could play exhibition games against a traveling club until April 15th when our season would begin. And I played a little for Welch in ’42. Five dollars a game, seven dollars for a doubleheader, seven dollars and a half. Now when he come back in ’43, he gave me ten dollars a game. I’m not on the team, I’m just a ballplayer he wants to have on the club to play, to make a good showing. Ten dollars a game and fifteen dollars for a doubleheader. I went for that. Well, naturally, I’m going to play for him until April 15th. When it come down close to April 15th, he asked me about going on the road with him. He was baiting me up real well.

The ball team would hang around at the biggest black cafe here. Bob’s Savoy Cafe. His name was Bob Williams. He had been in New York and stopped — like the old song say, “Stop at the Savoy.” He had been in New York and he named his cafe Bob’s Savoy. I played basketball for him — he’d have a basketball team around here. We were sitting there talking and Welch asked me about going on the road with him; how much he’d pay me — I think it was three hundred dollars a month, and two dollars a day meal money. In the meantime, Bob who owned the place came around and made a statement to Welch. As I said, Welch was manager for the Globetrotters. Bob said, “That nigger can play basketball, too.’’

Welch said, “What?”

He said, “Yeah, he’s my star player.”

He gets on the phone and calls Abe, Abe Saperstein. See, at the time, Abe was in the background for the Black Barons. He’d get all the booking and everything for the club, ’43, ’44, ’45. The owner was just getting a percentage out of it, because he was afraid of transportation, getting gasoline and stuff like that.

So he called Abe, and Abe said, “Give him three hundred and fifty dollars, if he can play basketball.”

I went with the Globetrotters three winters. Played basketball for them ’43, ’44, ’45. Summers I played baseball with the Birmingham team. I played outfield some and first base some. I left home as an outfielder, but the first baseman had to go in the army. So I came in to first base. In about the middle of the season — all games didn’t count, just when you played a team in your league and your division. Like you played the Homestead Grays, that game didn’t count, it was just an exhibition game. But the games you would play against teams in your division would count. We had lost four league games, and we were playing Memphis. And our shortstop — we had lost four before this one, this one made the fifth one, the first game of a doubleheader Sunday. We played those four games and he was in four of em, losses. He made an error in the fifth one, and we lost that one. So between the games of the doubleheader, the manager said, “Boy, you going to play shortstop for me. I’m sick of this.”

I said, “Man, I haven’t played any shortstop for years.”

He said, “Well, you’re going to play today. Come on, I’ll hit you some ground balls.”

I finished the season that year at shortstop. He moved the shortstop to third and moved the third baseman to left field. It was a heckuva infield combination. We won the pennant.

Birmingham was in the Negro American League. We played teams in the league and out of the league, also. We won the pennant in ’43, ’45, and ’48 — I was managing in ’48. And every time we’d win over here, the Homestead Grays would win their division out there. The year that Cleveland won, I think Newark won; and the year Kansas City won, I think Newark won. And each year the two division winners would play in the World Series, Negro World Series. Homestead Grays beat us every time we got there. We carried em to the limit in ’43 and ’45. In ’45 we carried em to seven games, but that was the year we had a car wreck. Our second baseman got tore up. We were riding in cars some, too, then. Our second baseman got broke all to pieces; and the third baseman — we were coming home to start the World Series — he got a hole knocked in his head; and the catcher, one of our catchers— we had two pretty good catchers — he got his arm hurt; and our utility infielder, which was a good pinch hitter and a powerful hitter, he got his leg hurt. So we were shorthanded, but we carried em to the limit. We never did win a World Series.

We’d carry not over nineteen — seventeen, eighteen men. Six pitchers or less than that. You’d have four outfielders and an extra infielder, two catchers. You’d have pitchers who could play another position, like pitcher/first baseman. That’s what kept many Negro pitchers from being real good pitchers, by playing two or three different positions. We never had over nineteen men, never. Our average team, when the team gets set, has about sixteen or seventeen. We’d have a twenty-two passenger bus, and wouldn’t nobody be on the back seat unless it was the material man— the guy that was the extra bus driver and handled the equipment. Material man, equipment man; he did the extra bus driving and took care of bats and balls. He’d put on a uniform and he’d play catch with us, but he was an older man. He’d get our socks washed, for those that wanted to pay him. He’d make all the trips, and he and the bus driver stayed together in the same room.

We were going into a small town in Mississippi to play. And the bus wasn’t running just right. The bus drivers had to be pretty good mechanics, which they were — some of em weren’t nothing but bus drivers, but the majority of em was pretty good mechanics. And our bus driver, God bless him, he saved our lives many a day. He could drive, he could drive.

They ought to pay the bus driver more than they pay the players, and I imagine some of the clubs did. I know Rudd made about four, five hundred dollars a month. And that was just what the average ballplayer on our club made. Average ballplayer then was making three-fifty, four hundred dollars. But the bus driver kept you alive and kept it rolling. I’ve seen Rudd, Charlie Rudd — well, the bus wasn’t running just right. One of the lift pins had broken, valve lifter had broken. And he said, “God almighty.” We had a couple of hours to spare, and we were close; we had time to make up the miles if we could get some transportation to get on in there. He said, “If I could get just one thing I’ll be all right.”

We were close to a farm, and he went out to that farmer’s fence. It had these long nails in there. He said, “I might get arrested.” But he knocked that board off and got one of those nails, and cut the head off of it, and cut that keen point off, and stuck it down in the engine compartment. And he said, “We can make it to town with this, without losing too much pressure.”

We made it to town and he bought a new lifter and he put it in while we were playing. He could drive!

A place where he could afford it, and the hotel had enough room, the bus driver stayed by himself. But places where the accommodations — like Greenwood, Mississippi, or Cleveland, Mississippi, and sometimes in bigger places — they had just enough rooms. Even the big towns, like Charlotte, didn’t have no big hotels, they just had big houses. Just like Memphis. Memphis didn’t have no big hotel for blacks until right before I left the league. Had big old apartment houses which they changed over to hotels. The place we stayed in Memphis for years was a big old apartment house right next to a drug store. Baseball players stayed in two rooms in the back. In the far room was the bath. Everybody used the same bath. Mostly all the hotels had a bath in the hall, including up to Indianapolis, Indiana. Chicago, New York, had the bigger hotels, the best hotels. Baltimore, we stayed in an apart-ment-hotel. Philadelphia, we stayed in a hotel. That was the biggest hotel we’d stay in. Kansas City had a hotel. Some big hotels didn’t want no ballclubs staying there. Worried that they’d keep up so much noise and tear it up. When they extended the block out of Chicago past Sixty-first Street, and they took over a hotel, a black guy we had met in Los Angeles was going to be the manager. He told us out there that winter, “I won’t be out here next year. I’ll be in Chicago.” Told us what he’d be doing in Chicago. “But I can’t take all of you. I’ll take guys like Bassett, Wilson, Davis, Britton —” guys that he knew. So about six of us would stay there.

See, they wanted guys that was clean and dressed nice because they didn’t want you sitting around the lobby of the hotel with a t-shirt on, or nothing like that. They got people like Joe Louis, Lena Horne, Dinah Washington, Lionel Hampton’s big band, they staying there. What they cared about was the image they showed when they walked downstairs. “Because we got people with noted fame staying with us. We got to keep our image up.”

The rest stayed down around Sixty-first Street on down to Thirty-fourth Street.

We knew beforehand where we were going to eat and where we would sleep. That was automatic. Club come in here, they know they going to stay at the Palm Leaf. They go to Atlanta, they going to stay at the Auburn Hotel on Auburn Avenue. You go to Kansas City, you going to stay at one of the two — they had two. They had one over there at the bowling alley; we stayed there most. Go to Tulsa, you going to stay at the little black hotel there — that’s where I stayed when I was in the Texas League. You go to Shreveport, you know where you going to stay.

Today it’s in the contract: A-accommodations, first-class accommodations. They stay in the top hotel now. We didn’t have no contract as such in Negro ball. But it’s in the organized contract, that’s one of the clauses. When they started signing black ballplayers, they signed the same contract — called for first-class accommodations. But they didn’t get it. That was on account of segregation. Of course, that was breaking the contract. But you know a guy wasn’t going to go against his living — maybe you had one out of a whole hundred who would.

So the black boys — Satchel and them stayed at the black hotel in St. Louis when he was with the Browns. Because we were there one night, we had played there when St. Louis come in, and Satchel stayed at the same hotel we stayed. I think it was called the Crystal White.

Sometimes we had to stay in jails. I’ve stayed in jails twice. No place else to sleep. One time, the Globetrotters was put out of a hotel in Blackfoot, Idaho. One manager checked us in, and the prejudiced manager put us out, the next morning. I used to kid the guys on the team, I’d say, “Man, they love me in the South. You fellas have been having the rough time. You don’t know where to go up here. You get refused. But I don’t ever get refused in the South because I know where to go. They got signs up for me to go. They got signs that say white go here and black go here. They look out for me. When I get on the bus they got signs say ‘Negroes’ and ‘whites.’ But you, here, you go sit down in a cafe and they liable to tell you, you ask em, ‘Do you serve Negroes?’ they say, ‘No.’” That happened many times in the Midwest.

The town we stayed in jail, we were playing in a fairgrounds. So we were walking from the jail — one thing, they fixed the place up where we could eat — we were walking to the place where we were going to play ball, and we said we’ll go out here and lay on this hay for a while where these horses been and sleep some more. We were walking and we passed by some homes, and up the street a little way two white kids were playing in the front yard. Well, one got after the other one and they ran around the house, and when they come back around the house we were right there in the street facing em — three or four big black boys, men, right there. And that one that was in front saw us. He squalled out and ran back around the house and come in and was peeping out the window. He had never seen a Negro live, I don’t guess, just on pictures. That night his father brought him to the game and got permission for the boy to touch us. He told the boy, “See there.”

I left here my first year with the Globetrotters, 1943. I had it in my contract that I’d be home for Christmas. So they would knock off three to four days at Christmas time, used to. And one way home would be on you, and Abe would pay the other way. So I was home on Christmas. I had to be back the day after New Year. New Years Day, went to the train station that night, my wife and children there to see me off. And when they said, “All aboard,” the black attendant put me up in the tail end of the car. He carried me around all the way through the car, and got to the section where the roomettes were, behind the toilets — and when he got to the end and had to make a turn, I said, “Hey, where you going, porter? We’re through the car, sleeping quarters.”

I had the drawing room, three beds for the price of three dollars and something a night. They give me three beds to keep me from sleeping in the compartment with whites.

And I told my wife, years ago, I had ideas that King had then, but I didn’t have the will power to go through with it. I always made expressions when I’m traveling, I put emphasis on, “Officer, do you know where I” — see, he looking right at me — “can get something to eat?” I never said, “Can you introduce me to a place that they serve blacks?” or “where Negroes can get something to eat?” I’d just say, “Can you tell me where I can get something to eat?” And places, public places where we would go, like filling stations, and I couldn’t use the rest room, I leave there, I tell him, “Take the gas hose out. Take it out.” And I go somewhere I can use the rest room.

After all the incidents that happened, I would sit down and talk to my wife. I’d say, “Look, you all ought to stay out of those stores” — some stores you couldn’t ride the elevator, same elevator as the white. I said, “You ought to stay out of those stores.”

They could have shook it up way before they did because I saw the gleam of the dollar in the white man’s eye. And I said, “I ought to have the FBI to go along with me and see how I am treated in transportation. But the FBI might be a Southerner; that wouldn’t help me any.”

Majority of black ballplayers, and those were just the mediocre ballplayers, all he was interested in was himself. We had some ballplayers, some good ballplayers, wouldn’t even think a dime about giving a nickel toward the NAACP. All they wanted was that money. He didn’t think about how good he could play. His desire is to get this little money right quick, in a half a year what it would take a whole year to make outside of baseball. Out of all the ballplayers that come in here, played with Birmingham, you got about four that you could walk in and say, “He’s paying toward a house.” Majority of them was renting. Because they didn’t want to spend that money on the road and send home toward a house, majority of the Southern boys — unless they had families that were a little bit established, and the father in the background already had a little something toward a home.

When I was about nine or ten years old, I was sitting there one night, I said, “Papa, can you own this home?”

He said, “No, kid, I’ll be paying rent on this house long as I live. Can’t own this house.”

I said, “I’m not going to stay anywhere where I can’t have me a home so if I get in trouble I can sell it and have a little money.”

I told him that when I was about nine or ten years old.

See, you would have your home here, and you playing ball away from here, your expenses is still going on right here. A lot of ballplayers just didn’t want to do that. They’d pull up, take their wives with em. Some of em send the wives to stay close to the mother, let the mother take care of em a while, then send for em and let em come out to where they were.

If you have a home, your children can say, “Come up to my house.” But if you didn’t, they might be ashamed to have you. “I would have you up there, but that little apartment is too little.” And I’ve always been interested in children and the whereabouts of children. I’d say, “You know where your child is?” That was one of my favorite statements. “You know where he is? You know he is between here and home?”

Our transportation broke down going into Omak, Washington, and we had to take a bus and leave one of our players with the car and trailer — traveling with the Globetrotters. So, called up the sponsor who was president of the Kiwanis Club, and also, he was an educator in the state system, and he was assistant principal of the high school. He was the sponsor. And he had us reservations at a hotel. But at the half of the game — we’d be playing cards, some guys would be scanning a old funny book or something — I was sitting in the corner of the locker room and he came in. He said, “Your reservation has been changed.”

I said, “Okay, we’ll talk about it after the game. Of course, you going to take us there anyway?”

He said, “Yeah.”

He took us to a old folks home. Give us the first floor — tall ceilings and had a grisly old heater in the middle of the floor. That’s where they changed our rooms to.

The next morning he called me up and said, “Hey, we having a luncheon today.” And if our transportation wasn’t there he was going to take us over to the next town at four o’clock that afternoon. And he said, “Reckon you fellas would like eating with us?”

I said, “Sure.” All road people like free meals because you don’t have to pay for it.

So he says, “Well, we start at twelve o’clock.”

I got em up. “Let’s go fellas, we got a freebee today with the Kiwanis Club.”

We went down and they had us on a stage. I’d never made a speech in my life, other than my graduation from high school. They introduced us — he introduced me and had me to introduce the Globetrotters. And when I introduced the Globetrotters, I sat back down. He got back up and said, “We’re happy to have the Globetrotters with us. Mr. Davis introduced his club — you know what, I would like to have Mr. Davis tell us about some of the hardships they have in their travels.”

Nothing — he hadn’t said anything to me before. So I got up, and I’m trying to get myself together — it was all these rich farmers and all like that, bankers — and I’m looking around. I said, “I’m not a speaker. I’ve always been in sports, where you’d have on a basketball team, you got four more fellas to help you out. On a baseball team, you got eight more other fellas to help you out. But making a speech, you all alone.”

I’m still thinking about what I’m going to say.

I say, “I notice you open up to the preamble of the Constitution of the United States whereby all men are created equal. Are we?”

Buddy, heads come out of those plates. Even the cook was sticking his head out. The waiters was stopping.

Then I told em, “You don’t see the true Negro. You don’t see him. All you see is actors.”

Then I said, “We’ve even had reservations changed at hotels.” And this was the hotel! But I didn’t know it, I didn’t know it. “We’ve never missed a date on our part.”

And after I finished, one guy was out there from Georgia. If I’d made that speech in Georgia, I’d been lynched. I’d been driven out of town, at least. He came up and said, “Don’t make that statement anymore that you can’t make a speech.”

The manager of the hotel came up. He said, “You had reservations here. I don’t know why it was changed. But let me know when you’re coming back. Drop me a card.”

The sponsor asked me to come to a general assembly at the high school, that evening, at two-thirty. He said, “Tell the kids the same thing.” I had a chance to dig up something then, and I told em — that’s where the true Negro came in. I said, “All you see is Stepin Fetchit, Allison that plays with Jack Benny, Amos and Andy. But you never hear” —I had a chance to get up some names, think about some names — “George Washington Carver. They don’t print too much about Ralph Metcalf, Eddie Tolan and all those guys. All you see is the black man in the movies. Because in some schools they don’t allow Negro history to even get in. You don’t know anything about the Negro that was making the clock, and making the coupling for the railroad car. You don’t know anything about that. It’s not publicized. A few of you may know, but you don’t study it.”

We were riding the bus, and our third baseman, if we rode all night and get to a town, he’d be standing up in the door so he could get a newspaper, run to the newspaper stand and get a newspaper. You’d hear some guy say, “I wonder what Joe Dimaggio doing this morning? Laying up in that big fine bed, done been out last night....”

One little old pitcher, he’d spend every dime he made, he say, “Always reading about them damn white boys, why don’t you do something yourself.”

I didn’t make those expressions, but you had guys that would. I’d just sit back and think em. Because in Negro Baseball we slept in the same bed, like husband and wife. I slept in the same bed with Steele. When I started, Tommy Sampson was my roommate and then Ed Steele. We got along very well, yessiree.

First time I played against Satchel was right here at Rickwood Field, in Birmingham, Alabama. He was with the Kansas City Monarchs. Ed Steele and I were playing with Acipco during the regular season, and playing with the Barons until April 15th. Well, the Barons and the visiting club would change at the same hotel downtown, because you couldn’t change at the ballpark at that time. No black club was changing out there, they was changing at the hotel. Palm Leaf Hotel, downtown on Seventeenth Street, on a corner above Brock’s drug store.

So, we were all changing clothes up there and Satchel was getting a rubdown from a trainer that he carried with him. Carried the man around to rub him down and be his valet. Welch told him, the manager of Birmingham told him, “You better get rubbed up good, because we going to get to you today.”

Satchel made a statement, said, “O, Welch, you got that same club you had down in Louisiana?” Was in a town that they had played earlier in the season.

Welch said, “Yeah. But I got a couple more that you haven’t seen yet.”

Satchel said, “Which ones are they?”

Welch said, “Those two right there.” See, I didn’t weigh but about a hundred and seventy-some- odd pounds then, about to hit eighty.

He looked at Steele, Steele was two hundred pounds, anywhere from a hundred ninety-five to two hundred pounds. He said, “Welch, that one there looks all right; but that other one, he too little, he too little.”

Welch said, “Well, I don’t know. That’s the one you might have to worry about.”

We went out there at the start of the game, messed around and got some men on. Satchel was asking Welch, who was coaching at third base, which one was I, coming to the bat. I was hitting behind Lester Lockett, I believe. And he walked Lester Lockett accidentally on purpose, just missing here and there. I came up and I said to myself, “I’ll just take one pitch to see what his ball does.”

He threw the first one overhand and it rose a little bit - a strike. I said, “O, it rises. Now I’m halfway set now.” Because I knew the curve ball had to be a slower pitch than the fast ball. He threw the next one three quarter and it tailed off on top of me. I pushed it off over our dugout, foul. Satchel looked at Welch and said, “He’s helpless as a baby now, Welch.”

Then he put his Satchel windup on me, gave me his motion that he had, threw me a fast ball and I just looked at it. Pfffftt. Struck out. I really didn’t see the pitch. It was fast.

Satchel’s fastball was as fast as Feller’s or faster, when he was young. I believe it might have been faster. Satchel had names for his fastball: fast fall, faster ball, and fastest ball. Changing speeds on his fast ball. You may recall, Satchel had a hesitation pitch. Pitchers was allowed any kind of motion they had at that particular time. He would bring his free foot over and let it hit the ground before he turned the ball loose. And he had a windmill windup. With nobody on he could wind up as many times as he wanted to. Some of Satchel’s best pitching was when there wasn’t many men on, when he could use that windmill windup. He could pop it. After playing with Satchel, I knew how and why he had gotten his pitching ideas and what he was doing. He was timing your pumps at the bat, your relaxation, and all like that at the bat. But he didn’t know hitters, he didn’t know faces. He wouldn’t remember a face from time to time at the bat.

I played with Satchel, barnstorming, just barnstorming. We played against the Feller All-Stars a couple of times. One time, in Los Angeles, Feller and Satchel agreed they would each go nine innings, didn’t care how bad either one of em looked. That’s what they did. Satchel struck out about sixteen or seventeen, Feller got about fourteen or fifteen. But we got eight runs and beat em eight to nothing. Feller didn’t have the stamina Satchel had. He wasn’t used to so many innings, just three innings every day. Satchel was used to it; he could go a long time.

One year we went east — see, we would go on our eastern trip once a season. Kansas City was the first club that started going east. Of course, they had names, Satchel and everybody, and people’d want to see em. We went out there in ’43 and we beat em all. First year we went into Yankee Stadium, it was a three-team doubleheader, and we beat the other two teams, we shut both of em out. We beat one by eleven to nothing, and beat the other about eight or nine to nothing. After that we were a kind of favorite out there.

So, this trip east we go with Kansas City. And we were playing a four-team doubleheader in Washington. Birmingham was playing the Grays, which was the favorite club - that was their hometown — the second game. Kansas City played the first game, but when Satchel got to the ballpark it was already the seventh or eighth inning.

He was a name, and Kansas City was a big name club, too. But he didn’t realize that we had gained as much fame out that way as Kansas City had. Without him. So they agreed, since a lot of fans came there to see Satchel, to let him pitch for us. We were playing the Grays. That’s how I got a chance to see him pitch against Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard in the same ball game. Buck Leonard hit in front of Josh. Satchel struck em both out, talking to em. He’d talk you out of a hit. Buck Leonard come up there and Satchel told him, “O, you a pretty good hitter. I’m not going to waste anything on you. Might as well get ready to hit.” And he struck him out. Then he said, “Josh, that goes for you too. You too good a hitter, I’m not going to waste any time on you.” He struck him out, too. Struck em both out and they knew he was going to throw fastbalIs. Buck Leonard was one of the best fastball hitters you want to see. Satchel’s ball moved, and he could put it where he wanted it. Buck Leonard hit third and Josh hit fourth. That was their lineup the first world series that we played, and that’s the way they hit most of the time.

Satchel was the best pitcher I ever faced, and the best I’ve seen. Because he had control; he wouldn’t walk about one or two men a ballgame.

One night he didn’t pitch three innings against us, in St. Joe, Missouri. That was one of the places Kansas City would play when they’d play at home. That night we beat em about nineteen to something. Satchel went out of there in the second inning. He didn’t pitch his three innings. Because we were lightning em up pretty good — but they was catching em. MacLaurin led off with one right back by Satchel’s head — leadoff hitter. The way he threw it, that’s the way it come back, right by his head. I don’t know what the next man did, but Steele — I believe Steele was hitting in front of me that night — Steele hit a shot. They caught it. I hit a long fly ball that Willy Brown caught. And old Satchel asked Welch, he said, “Hey, Welch, what you been feeding em, man?”

Welch said, “Ahhhhhhhhh, we going to get to you, we going to get to you tonight.”

Satchel said, “I don’t know about that because I aint going to be out here long, that’s for sure.” Because he was scheduled to pitch in Kansas City when they got there. So he didn’t pitch but two innings.

Now it was sort of a fairgrounds ballpark, and it didn’t have no dugout as such. They just attached em to the stands, at the same level. The bathhouse was down there even with first base. After Satchel went in to change clothes, he heard all the people hollering. And when the ballboy come running around there getting the balls, Satchel would stick his head out the door, say, “Hey, kid, what’s the score?”

The boy’d say, “O, about five to nothing or one, favor of the Birmingham club.”

A little later on, he’d hear the hollering, he’d say, “Hey, kid, what’s the score now?”

“O, about twelve to something.”

“Jesus Christ.”

He told Welch after the game, “You know, that whuppin was for me. If I’d stayed out there they probably woulda done the same thing to me because they was hitting me.”

Satchel was around a long time, just like Campanella was around a long time. Campanella started when he was about sixteen. If I’d a made my appearance in the Negro League when I started in traveling ball, I’d a been around a long time. Because I started when I was eighteen — traveling ball. Didn’t nobody see me but country people. In our league we used to say that about a team that was traveling; you didn’t play nowhere but out in the sticks. The only traveling club that played in big cities was the Indianapolis Clowns. All the other clubs would have to play out here in Bessemer, Tuscaloosa, Dothan, places like that. If they got in the big towns, they would have to play the big local club.

Once or twice a year, we would play a local club on the road. But they had known names, like Fort Wayne. That was the first local club we played in ’43, close around where they live. We won the first game of the series, and they was advertising, “Black Barons, winners of the first half.” We go in there to play them the second game and boy, we were looking worse than a sandlot team. Had one — you know, they got a star-ruler in every ballpark — and this fellow was up in the stands hollering, “Black Barons, my eye.” The team had us about five to one. But our old favorite statement was, if you play a local ballclub, if you can just stay close to em you can beat em from the seventh inning on. Because they get tired. Take a local ballclub playing two or three times a week, they’re never in top shape. And we started getting to em about the seventh inning. You talk about shots — shots was hit. We hit the wall and over the wall. The guy in the stands said, “Well, I think I’ll have to take that back.”

You don’t hear too much about a lot of Negro ballplayers, good ballplayers, because the whites wasn’t paying attention to em. Josh Gibson was known; he hit a lot of home runs, he was powerful, he was close to a city where he might get it in a white paper. See, all of our publicity came from two papers, the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender. And if you didn’t have anybody in your town with the initiative to send it in, they wouldn’t get to know about you.

Take Sam Bankhead — best arm in baseball from shortstop. One time Cepeda’s daddy was playing first base for us in Puerto Rico, and Sam at short. Well, Sam threw hard when he had to. A lot of players got a style where they just throw good enough to get the guy out. But when they really had to throw, they would fire the ball. That’s one of the difficulties in white scouts scouting black ballplayers. Because they didn’t throw the ball, they’d flip it. They’d fire it when they had to, then they would show it to you. After talking with white scouts and being with them, I found out all this. I’d say, “He got a good arm, he just won’t show it to you. I believe he got a good arm, but he’s flipping it all the time.” Now me, out of the hole, at shortstop, when I go get a ball in the hole and going for a double play, I didn’t throw it, I flipped it.

So, Bankhead threw one to Cepeda — this is Cepeda’s daddy. He just threw it over there ordinarily. And when Cepeda going to put on his show — we call it, “sport it,” or whatever term you might want to use —he stretched out, but the force from the ball wasn’t much and he dropped it. Now he out there going to show Bankhead up. He talking in Spanish, but a couple of guys could understand Spanish and told us what he said. He said, “You got a good enough arm, why don’t you throw the ball?”

I could speak a little Spanish, too. I said, “You hear him, Homey?”

Bankhead said, “Yeah, I hear him.” And Cepeda was a little nasty, talking about “that s.o.b.”

About the fifth or sixth inning, Bankhead got a two hopper. When he was going to throw hard, he’d tiptoe like a pitcher on a pitcher’s mound, raise up on his foot and push off. Partner, he raised up on that tiptoe and threw that ball — never got very high off the ground. Cepeda’s daddy, when he saw it coming, he started backing off and he caught it moving away from it. When we went in the dugout he put his arm around Bankhead and said, “You throw the ball like you want to all the time. You throw just like you want to.”

A lot of good Negro ballplayers was over the hill when I came along. John Henry Lloyd, he played before my time. Mules Suttles, I played against him once in an exhibition game right here. I was working at Acipco then, and he was on an all-star team. Mules Suttles, first baseman, he was old then. I couldn’t rate Cool Papa Bell because he was going over the hill when I arrived. I played with him once in an all-star game, and against him all other times with the Grays. Oscar Charleston, old man, they say he was a good ballplayer. I only saw him standing on the coaching line. Martin Dihigo, I played against him when he was with the New York Cubans; but he was old then. Luis Tiant’s daddy was on that team. Good pitcher — but I didn’t see enough of him, he was old then too. He still had the best move in baseball. He caught John Britton twice in one ballgame. First he got on base, Britton took his lead. Not as big a lead as he would ordinarily because we had been warned that Tiant had the best move in baseball. So Britton led off with a single right back by his head, but he didn’t take the usual lead that he would have taken against any other pitcher. Tiant picked him right off. The next time up Britton walked, which was rare because he was a bad ball hitter. He took his lead off first, just about a step and a piece from the base, and he standing there saying, “I’m not going to get picked off this time.” And he standing there when he got picked off. Didn’t move until the ball was on its way. Got charmed.