This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

“Their Joy and Gratitude Can Only Be Imagined”

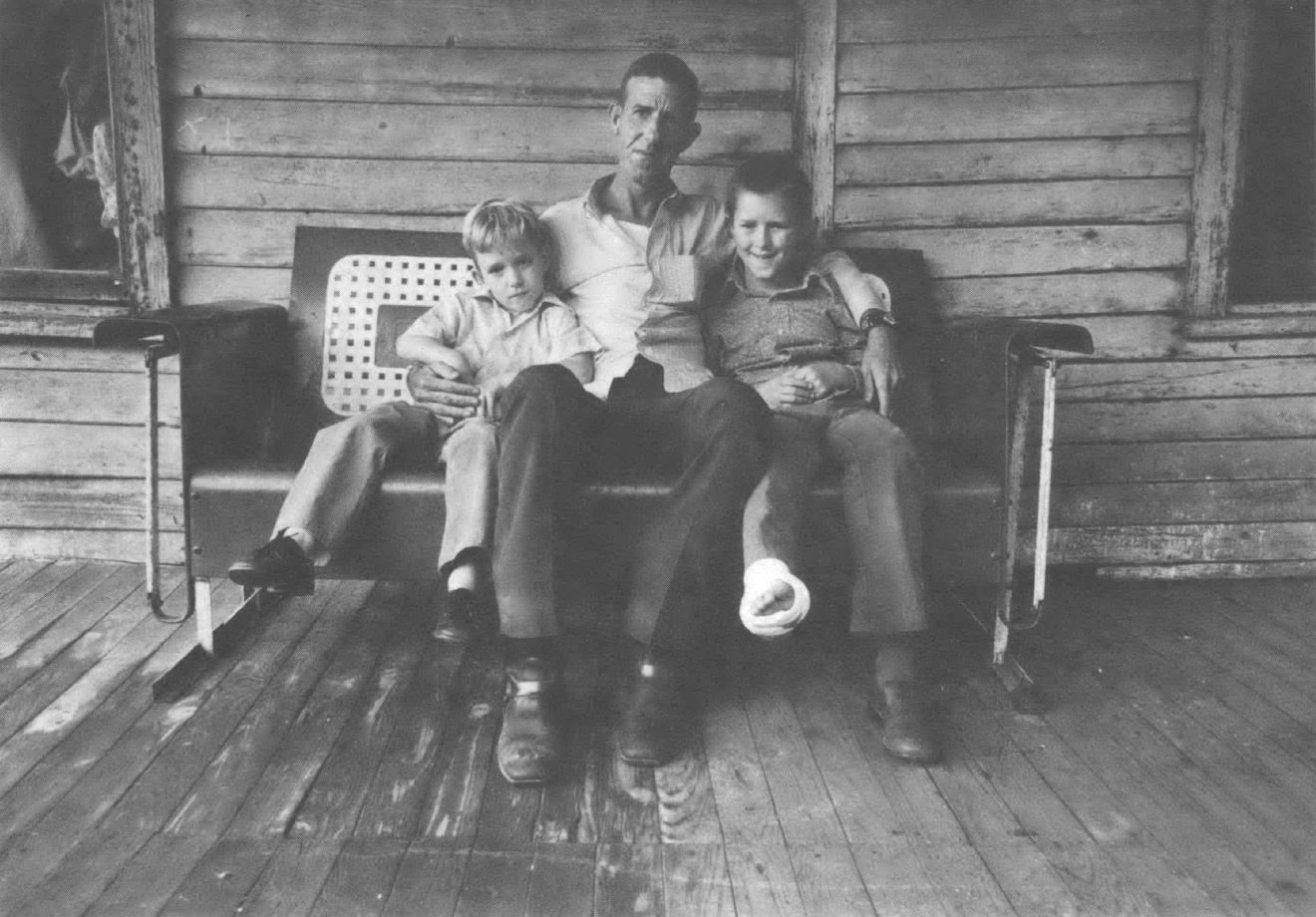

“What the doctors from the UMWA Funds saw was beyond belief — paralyzed men (paraplegics) who had not been out of bed for two, eight, seventeen, or twenty years, the story of their pain and despair deeply written on their faces. Bladder and bowel control had often been lost with the injury, and they were unable to care for their simplest needs. The men described their pain — ‘It’s just one deep, lasting ache,’ or ‘It hits me about three or four times a day, like someone jabbing a big electric rod through my legs.’

“Some were in windowless shacks, fed and cared for by their neighbors. Others were cared for by devoted wives and other members of the family. Some had not seen a doctor in years. All required the entire time of one or more other persons to keep them alive and provide such limited assistance as untrained hands could give.

“If was explained to these men and their families that the Fund was prepared to send them to some of the leading medical centers of the country, where everything possible would be done to relieve their suffering and develop and train their broken bodies, so that they might be able to move about and care for themselves. In some instances, it was suggested that they might be able to learn some new kind of work for which they might be paid. When they finally realized that they were listening to the truth, their joy and gratitude can only be imagined. ...”

— excerpted from an early UMW Fund Annual Report

When the doctors from the UMWA Health and Retirement Fund first set foot in the Appalachian coalfields during 1949, they found themselves surrounded by the human wreckage of a medical disaster area. Mangled bodies, discarded by the coal operators, were piling up. Health care, hospitals, physicians and sanitation were unknown to many of the neglected mining families nestled deep in the mountain hollows. When limbs were severed or a sickness lingered, miners in the coalfields had but one choice when they needed care — the infamous “check-off’ doctor. Since the mountains had always been medically underserved, coal operators made regular deductions from the miners’ paychecks to guarantee a steady income for the coal companies’ chosen physicians. These “check-off” doctors made no regular examinations, but by their arrangements with the coal companies, they owned a monopoly on health care in the mountains.

John L. and His Fund

This medical monopoly was finally broken in 1946 when UMWA president John L. Lewis negotiated a contract providing for a royalty of five cents per ton of mined coal to support a union-controlled Health and Retirement Fund. The contract agreement came only after negotiations with the coal operators became deadlocked, and President Truman seized the mines. In negotiating with the government’s representative, Interior Secretary Julius Krug, Lewis won his demand for a health fund coal royalty which the industry had rejected during the previous year’s negotiations. The historic Krug-Lewis agreement also ordered a survey of medical and sanitary facilities and health conditions in the coalfields.

Nowhere were the detrimental effects of the operators’ policies on miners’ health better documented and exposed than in The Medical Survey of the Bituminous Coal Industry, conducted under the direction of Navy Admiral Joel T. Boone. Commonly called the Boone Report, this study represented the first comprehensive medical survey of an industry ever undertaken by the government. By cogently documenting the deficiencies of coal operator-controlled health care in the mountains, it laid the essential groundwork for developing a miner-controlled health care financing and delivery system. The Boone Report cited a wide range of medical and environmental problems, pointing out the undesirability of the “check-off’ doctors, the inadequacy of three-fourths of the coalfield hospitals, and the glaring deficiencies in transportation, housing and sanitation in mining communities. Especially in the southern Appalachian region, the report noted that primary care was provided by an insufficient number of inadequately trained and poorly motivated physicians and that specialist care and hospitals were simply not available.

The creation of the industry-financed Health and Retirement Fund by Lewis made the coal operators financially responsible for the health and welfare of miners and their dependents, from the cradle to the grave, and started a revolution in health care delivery throughout the coalfields in the South and Midwest. Bargaining for the Fund came at a time when World War II wage controls forced the UMWA to develop innovative benefit demands at the bargaining table. Over the next several years, Lewis gradually upped the coal operators’ royalty payments and gained increasing administrative control over the Fund itself.

By October, 1952, the Fund’s royalty payments had been increased to forty cents per ton; Lewis was now chairman of the Fund’s three trustees, and his close confidant, Josephine Roche, occupied the key position of neutral trustee. In day-to-day administration, this arrangement gave the union decision-making control, but as Lewis noted at the time, “the operators’ veto power on this fund rested in the fact that at the end of each con- tract period they could, if they would, discontinue it by refusal to continue it.”

And there were other drawbacks. By tying the Fund’s financing directly to the industry’s production output, Lewis had made the miners’ health and welfare benefits vulnerable to the boom and bust cycles of the coal industry. Throughout the history of the Fund, the cruelness of this irony has haunted miners in the coalfields, particularly during the early ’50s, when the coal operators began to introduce mechanization to increase productivity. In the process, many miners lost their jobs to machines — machines which made coal mining more dangerous for the miners who remained by increasing both the safety hazards and the dust levels in the mines. Ironically the Fund’s improved financial status, and the subsequent development of a revolutionary health care program in the coalfields, were accompanied by increasing industry-caused health and welfare problems for miners and their communities.

Serving the People

As the newly appointed Executive Medical Officer of the Fund, Dr. Warren F. Draper came with impeccable credentials both in public health and organized medicine. He had served as Deputy Surgeon General of the US Public Health Service and as a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates from 1924 to 1946. His credibility and stature were to prove invaluable to the Fund in its struggle to provide “comprehensive, accessible, quality care at reasonable cost” to miners and their families throughout the coalfields.

Draper began by opening area medical offices in ten locations throughout the coalfields. Each medical office was directed by a physician administrator who was directly responsible to Dr. Draper and his staff. These physicians comprised one of the most progressive groups of health care professionals of their day and were committed to establishing a model health delivery system based on prepaid care.

Their first task, and one of the boldest and most stirring efforts of the Fund, was to seek out the broken and disabled miners and provide them with previously unheard of rehabilitation and medical care. A vast campaign involving union officials, local record searches, and the questioning of knowledgeable local citizens was undertaken to locate mine accident victims. Once found, crippled miners who had not been out of bed for months, years, and even decades were carried, in stretchers, by friends and ambulance crews, to places reachable by vehicles, which were then driven to the chartered planes and Pullman cars which transported them to the best rehabilitation centers of their day.

According to Dr. Draper, “This arduous, costly task of restoring men with crushed limbs and backs in the terrible toll of the coal mines is one of the finest chapters in the history of medicine.” By the end of 1955, 97,000 disabled miners had received rehabilitation services. About 6,500 of them had been able to return to the industry; 15,000 found work in other industries; 5,800 became self-employed. Of 1,113 who had spent their lives in bed before getting such care, 1,041 were enabled either to walk or get around in wheel chairs.

When Draper and his administration began, they conformed strictly with the practices of traditional, doctor-dominated medicine. Free choice of physicians was the rule and services were paid for in fees. But as the Fund’s area medical offices reviewed bills and medical records from doctors, they began discovering myriad abuses, similar to those presently associated with Medicare and Medicaid— unnecessary surgery, over-hospitalization, and price gouging.

Draper wasted little time in explaining his position to his former colleagues in the medical establishment. In a speech before the AMA, he set forth basic principles which would guide the operation of the UMW Fund in the years ahead: “I think that free choice of physicians should be limited to physicians who are willing to conserve the resources of the paying agency to the fullest extent possible. It is not reasonable to expect us to pay physicians who needlessly send to the hospital cases which do not require hospitalization and whose rates of admissions are much higher than the rates of other competent physicans. We are within our rights to limit our choice of physicians to those who are willing to conserve the resources of the Fund and play fair with us.” The UMW Fund’s precedent-setting efforts to secure high quality care at a reasonable price angered both coalfield physicians and doctors across the country.

As protests from local coalfield medical societies became more vehement, the Fund stopped its automatic reimbursement of doctors’ fees and hospital charges and began an ambitious program to reform health care delivery with a three-pronged attack on excessive hospitalization costs and monopoly control of coalfield health care.

First, the Fund began to replace the uncooperative coalfield doctors by organizing and financing, with the help of union locals, a series of group practice clinics throughout the mountains to provide coordinated, comprehensive primary health services to the Fund’s beneficiaries and other members of the coal mining communities. These nonprofit clinics, run by consumer boards representing the local communities, were staffed by physicians who were either paid regular salaries or put on a monthly retainer to cover all necessary care provided to Fund beneficiaries. The clinics stressed preventive medicine and became the first one-stop medical service centers in rural America. As a result, they reduced hospitalization, surgery, and overall medical costs.

Next, Draper ordered that no Fund beneficiaries would be hospitalized unless approved by a qualified specialist, in order to avoid unnecessary surgery and prolonged hospitalization.

For the third prong in its attack, the Fund tackled the problem which the Boone Report had so forcefully documented — the lack of hospitals in southern Appalachia. The Fund set up a non-profit corporation to finance the construction of ten hospitals throughout Kentucky, West Virginia and Virginia. The Miners’ Memorial Hospitals were a bold step forward in the regional planning of health services and they were touted as a first for the rural South, as well as a model for the nation and the world. Provision for large outpatient services and hospitalbased ambulatory care — a cost-saving innovation at the time — was a central concept in both their construction and operation. The first hospital opened its doors in December, 1955, the tenth in May, 1956. In addition to providing sorely needed, well-equipped modern beds and sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic facilities in areas essentially devoid of these services, the Miners’ Hospitals made it possible to recruit and train high quality health professionals for Appalachia, many of whom were the sons and daughters of coal miners. Other hospitals in the area improved their facilities, while some of the smallest and most wretched were forced to close.

In response to the Fund’s vigorous intrusion into health care delivery in the mountains, state and local medical societies passed resolutions condemning Draper and the Fund. Some doctors refused to refer their patients to the Miners’ Memorial Hospitals. In areas where the miners’ clinics were established, local medical societies tried to ensure that clinic physicians were systematically denied hospital privileges in local hospitals.

For example, physicians associated with the Fund’s Bellaire clinic in Russellton, Pennsylvania, were not able to obtain local hospital privileges from 1952 until 1965. During the thirteen year interim, they were forced to send patients needing hospital care to Pittsburgh. When the Fund removed the hospital from its participating list, the medical staff accused the physicians and the Fund of pressuring the hospitals and their staffs “to accept the dictatorship of the UMWA Fund.” In an advertisement in the New Kensington daily newspaper on April 21, 1959, the medical staff of the Citizen General Hospital accused the Fund of depriving “the individual of one of his precious American ‘Rights’ — ‘The right of free choice.’ The power hungry leaders of this and similar movements in our country today preach free enterprise... but they are working for...false socialized economic security ...and socialized medicine.”

In one of his more candid moments, a local doctor called the clinic physicians, “a bunch of young punks come out here to try [to] cut into my $30,000 a year practice.” In a letter to Les Falk, Area Medical Director for the UMW Fund, the president of the board of trustees of the City Hospital of Bellaire commented on the removal of four physicians from the participating list: “It is beyond our comprehension how an outside agency such as the United Mine Workers Fund should or can take upon itself the prerogative of judging the quality of medical care provided by these physicians and overriding a committee of their peers.”

In 1963, after having been denied privileges for more than ten years, Bellaire Clinic doctors and some of their patients finally instituted suit against the City Hospital of Bellaire, “its trustees, the medical society and various individuals, charging them with conspiracy in restraint of trade, violation of public policy and violation of the Ohio Valentine Antitrust Act.” This suit was finally won in 1965. The court directed the hospital to grant privileges to the group members. Local and state societies fought back by charging the clinic medical groups, their individual members and Area Medical Administrators with unethical conduct, including allowing the Fund to control their practice of medicine, soliciting patients, and denying patients the right to “free choice of physician.” In every case, these charges were eventually proven false or dropped, but by then organized medicine had developed other strategies of attack. In Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Illinois, state medical societies wrote all their members directing them not to deal with the Fund. Despite this pressure, most coalfield doctors continued to treat beneficiaries and bill the Fund.

The Fallout

When the bottom fell out of the coal industry in the late 1950s and early ’60s, the number of UMWA miners dropped from 400,000 in 1945 to 200,000 in 1955 to 90,000 in the early ’60s. As a result, fewer and fewer patients in the Miners’ hospitals were Fund beneficiaries and the hospitals became an ever-increasing financial drain on the Fund, which was already experiencing financial difficulties due to decreases in production and a royalty rate that had remained at forty cents per ton since 1952. The Fund initially responded to the financial crunch by tightening eligibility requirements. In 1960, 35,000 miners who had been out of work for more than a year lost their health cards in a single day, along with thousands of widows and other dependents.

Still suffering from financial problems, the Fund put the Miners’ Hospitals up for sale in 1962. The Board of National Missions of the United Presbyterian Church purchased the hospitals for $8 million, almost all of which was provided by the federal government after the personal intervention of President John F. Kennedy. Had Medicare and Medicaid been available then, the Fund might have been able to keep the hospitals. As it was, neither federal aid, which made possible the purchase of the hospitals, nor state aid, which paid for indigent patients in the hospitals once they were acquired by the Board of Missions, were offered the Fund.

Rank and file miners, who were never consulted about this giveaway of one of their most valued possessions, carried on wildcat strikes to protest the Fund’s decision. As if it were a harbinger of an event still fifteen years in the future, the union leadership turned a deaf ear to the miners’ cries, as the foundation of their cherished health care system was sold out from under them. During its first twenty years of operation, the UMWA Health and Retirement Fund developed and pioneered more innovative ways to control the cost and quality of health care that are only now being re-discovered and recommended by health advocates and reformers across the country. The Fund developed a closed panel of participating doctors who, by accepting reimbursement from the Fund, were cooperating with a regional program of comprehensive care, consumer control, and hospital use and cost containment. At the same time that the Fund pioneered and financed the first consumer-controlled comprehensive health clinics and First independent regionally coordinated hospital system that rural America had ever seen, it also contained the cost of health expenditures.

The Fund’s role in improving the occupational health and the general welfare of beneficiaries, was, however, much more limited than its role in improving the coalfield health system. Although Dr. Lorin Kerr did much of his early work on black lung under the auspices of the Fund, its involvement in occupational health issues was limited by the presence of the management trustee, by Lewis’ commitment to labor peace and industry mechanization, and by his claim that the union itself was responsible for health and safety on the job.

The Fund also left such issues as housing, sanitation, water supply and sewage disposal to public health departments which were most often inadequate to the task, especially in southern Appalachia. The Fund’s intervention and financial support began with preventive medicine and never really moved into environmentally caused diseases.

Reform Effort

As the Fund income decreased and costs rose during the late ’60s and early ’70s, the corrupt administration of union president Tony Boyle manipulated Fund eligibilty requirements and benefits and maneuvered union finances for his own personal gain and to the detriment of the Fund and its beneficiaries. From his dual position as UMWA president and Health and Retirement Fund chairman, Boyle kept between 14 and 75 million dollars of the Fund’s assets in non-interest bearing accounts in the UMW-controlled National Bank of Washington.

During the late 1960s, numerous suits were filed against the Fund and Tony Boyle. One of these, Blankenship v. Boyle, was brought by Harry Huge, a Washington attorney, on behalf of 17,000 miners and widows who charged the trustees and the union with mishandling the Fund’s assets and the arbitrary and capricious determination of eligibility for Fund benefits.

In 1971, Judge Gerhard Gesell ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and ordered in part:

• That a new board of trustees be appointed with the neutral trustee subject to approval by the government.

• That the Fund have no financial dealings that would provide collateral advantages to either the union or the operators.

• That the application forms and process make clear that union membership is not required to obtain benefits.

• That eligibility for pensions was to be based on specified length of service requirements and applied in a reasonable and consistent fashion.

As a result of the Blankenship court decision and the Miners for Democracy reform movement led by Arnold Miller, drastic changes took place within the administration and structure of the Health and Retirement Fund. Shortly after Miller was elected president of the union in 1973, he appointed Harry Huge, the attorney who had fought for the Fund’s reform, as the union representative among the Fund’s three trustees. Huge, in turn, convinced the other two trustees to hire Martin Danziger, a lawyer administrator from the Justice Department, as the new director of the Fund.

Danziger and many of the other newcomers to the Fund were not trained in pensions, or health, or coal. Their speciality was a style of management defined as a service separate from the content of what is to be managed. And in some ways content became much less important to the Fund’s health program than it had ever been. The new managers placed great emphasis on administrative documentation, written procedures, and the business-like conduct of affairs. While their attitude was quite understandable in light of the Blankenship decision, the Fund’s new managers undervalued the skills and contribution of many who had forged and directed the Funds health program for twenty-five years.

Many of the old time health people were fired, downgraded, or simply resigned. There were tremendous conflicts in personality, working style and commitment between the old timers and the newcomers, and very little trust. As physicians and administrators left the Fund, they were either not replaced — the Fund was without a Medical Director for over a year — or replaced by people with more limited experience and a different orientation to health care delivery. Thus, when critical program decisions were made, such as the July, 1977, cutback in benefits, they did not reflect the Fund’s historical commitment to the prepaid clinic/salaried physician model of care.

1974 Contract

The new management made significant changes in the organization of the Fund. Medical bill paying was centralized. It was determined that the kind of record-keeping required to comply with ERISA (Employee Retirement Income Security Act) and other information needs of the Fund could no longer be stored or processed adequately by hand. Because it seemed clumsy and outdated to manually handle $250 million worth of health services annually, the Fund computerized its records in a crash program during the life of the 1974 Contract.

Any change so drastic as centralizing and computerizing the bill-paying and record-keeping functions of an organization as large as the Fund creates a degree of chaos. Payments to providers were slowed down, and control over services and charges — once maintained by looking at each bill coming into the Area Medical Office — was lost before the computer could provide adequate replacement data.

In addition to procedural changes, the new Fund management was reluctant to intervene in the health care system. Local offices were forced to relax their demands upon health care providers both because the Fund could no longer promise prompt and accurate payment, and because there was little support in Washington for strict cost controls. New management policies also forced a dramatic retreat from direct or personal health service to beneficiaries. The Fund had done case findings among its beneficiaries — originally to seek out miners in need of rehabilitation. Field staff had arranged for referrals and social services, visited miners in hospitals, made medical appointments, given personal health education and provided discharge planning. These services were systematically dropped as uneconomic and inappropriate for the Fund. Staff were instructed to find local agencies charged with these functions and refer beneficiaries to them. The Fund’s role in providing technical assistance and special Financial aid to providers was also sharply curtailed, further diminishing its role in the lives of beneficiaries. The Fund began to look more and more like other third party payers, like an “insurance company with a heart.”

As a result of payment delays and mistakes, the Fund lost much of its credibility and clout with health care providers and with many miners. Its long history of active support and control over the community clinics was replaced by increasing scrutiny of costs, elimination of subsidies for the care of non-Fund beneficiaries, and an erosion of its faith in the efficacy of group clinics in favor of the standard fee-for-service solo practice.

In addition to the Fund’s new management practices, restrictions in the 1974 Coal Wage Agreement further eroded its support both in the coalfields and in the public health community. The 1974 contract called for the division of the Fund into four separate Trusts. The 1950 Benefit Trust was established to pay for health care, death and survivor benefits for miners retired before December 31, 1975; and the 1950 Pension Trust paid pensions to these same beneficiaries. Two similarly divided 1974 Trusts were set up to pay benefits and pensions to working miners and miners retiring after December 31, 1975. The important thing about this division was that miners retiring under the 1974 contract divided Fund beneficiaries into two unequal classes in order to raise the pensions of working miners, while also forestalling a dramatic increase in royalties for the coal companies.

Divide and Conquer

Why was the Union willing to divide its membership? Why were the 80,000 miners retired under the 1950 Trust limited to pensions of $250 per month while 1974 beneficiaries were eligible for pensions averaging $425 depending on age at retirement and years of service?

When the 1974 Coal Wage Agreement was negotiated, the UMWA was having a difficult time organizing nonunion mines — both the new strip mining operations in the Western part of the country and those in traditionally anti-union parts of Appalachia, particularly Kentucky. Operators at the non-union mines began telling their workers that joining the UMWA would mean shouldering the financial burden of the 80,000 retired miners covered by the Fund. Many non-union companies also increased their employees’ wages by an amount equal to the health and retirement royalties required by the 1974 contract, giving them cash in hand instead of payments into the financially ailing Fund. The UMWA was further pressured by the realization that demanding pensions at the 1974 Trust level for all miners would have necessitated a royalty increase which would have driven marginally profitable union mines out of business, adding more problems to organizing.

As the 1974 contract went into its final year and a half, the 1950 Benefit Trust began experiencing severe financial difficulties. By the terms of the 1974 contract, reallocating money between the different Trusts was the prerogative of the coal operators and the union, not the three trustees of the Health and Retirement Fund. At a time when health care costs were rising and pensioners’ buying power was falling, the Fund was placed on the chopping block between a strife-torn union and a profit-hungry industry. In May, 1976, the union and the Bituminous Coal Operators Association (BCOA) agreed to stave off disaster by reallocating income from the 1950 Pension Trust to the 1950 Benefit Trust. Another reallocation in October, 1976, transferred income from the 1974 Benefit Trust, which had $60 million in reserves, to each of the other three Trusts.

This second reallocation played a critical part in the financial dealings which quickened the death of the Fund. Two aspects of the transaction appear suspicious. First, the trustees of the Fund requested only that income be transferred from the 1974 Benefit Trust to the 1950 Benefit Trust. Instead, the UMW and the BCOA shifted income from the 1974 Benefit Trust to each of the other three Trusts, completely eliminating two months of contributions to the more recent Benefit Trust.

Secondly, working miners incurred out of pocket expenses of $30 million for health benefits between July, 1977, when the benefits were cut back, and December, 1977, when the 1974 contract expired. Had the $60 million not been transferred, the health benefits of working miners could have been paid in full for the entire period.

In early June, 1977, the coal operators refused to reallocate funds to stave off cutbacks a third time. Joseph Brennan, president of the BCOA, said that another reallocation would constitute “a stamp of approval for wildcat strikes” which were sweeping the coalfields. The coal operators claimed that the wildcat strikes were the cause of the Fund’s financial short-fall, drawing attention away from their own miscalculations and punitive manipulations of the Welfare and Retirement Fund. Coal production — and therefore Fund income — was adversely affected by wildcats, a harsh winter and extensive flooding; but the largest loss of income was due to the coal operators’ failure to open new mines that they had planned when the projections of Fund income were originally calculated for the 1974 contract.

On June 20, 1977, a few days after the close re-election of Arnold Miller, the trustees announced a cutback in health benefits in order to prevent a build-up of unfunded liabilities in the two Benefit Trusts. Beginning July 1, all beneficiaries would be responsible for the first $250 of a hospital bill, and forty percent of all non-hospital care up to $500 per family. In addition, all retainer arrangements with clinics and other providers were cancelled. Henceforth, all charges were to be billed on a fee-for-service basis.

The immediate response in the coalfields was a wildcat strike which involved some 90,000 miners for ten weeks. The clinics also protested, explaining that they would not be able to operate their programs on a fee-for-service basis and began to cut back on services and personnel.

The cutbacks themselves put the union in the humiliating position of entering the negotiating sessions for the new contract struggling to regain benefits that had already been won in the previous contract. The union leadership’s inability to control wildcats and unwillingness to support them, plus the charges that the announcement of the cutbacks was timed to ensure Miller’s re-election, further weakened the credibility of the union both with the BCOA and the rank and file.

Who Killed the Fund?

In retrospect, there is reason to believe that the coal industry intentionally orchestrated the financial crisis within the UMW Health and Retirement Fund in order to regain autocratic control over its workforce, break the power of the UMWA and, once and for all, rid itself of the financial burden of the human suffering of its workforce.

It appears that the Fund is dead as a provider of health benefits for the miners. The new contract allows each operator to insure its workers through private, profit-making insurance companies and provide them with the standard fee-for-service benefits which have created so many problems in the health system.

Since the Fund subsidized clinics throughout the coalfields (and consequently the care of much of the medically indigent population in these regions), and since it is extremely doubtful that any Blue Cross/Blue Shield, commercial insurance or other operator-sponsored plan will continue such subsidies, it is likely that many clinics will be forced either to drastically reduce their services or shut down completely.

The end of the Fund has implications beyond the health care system. For miners it may be the beginning of the end of national contracts. Portability of benefits — the ability to transfer health and pension benefits from one operator to another within the industry - may be threatened. And of course, neither the union nor the miners will have a say in the administration of company-provided benefits.

The UMWA Fund was one of the first industry-wide collectively bargained health plans in America. It attempted to establish a model health care system for workers in a single industry, and was successful in implementing innovative concepts in public health, including regionalization of care, comprehensive health centers, limited prepayment schemes, and the use of salaried physicians.

The Fund represents thirty years of history and practice in innovative rural health delivery and in struggle with organized medicine to improve health care. Those who continue the struggle have much to learn from that experience.

Tags

Barbara Berney

Barbara Bemey, who holds a Masters in Public Health from UCLA, was employed by the UMW Fund as a health analyst until January, 1978. (1978)