This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

Even now, years later, almost no one in the sleepy north Georgia town of Hartwell likes to talk much about what happened that day in July.

The folks who have been fighting for 13 years to win a union contract at Monroe Auto Equipment Company’s Hartwell plant remember the events quite clearly, though. For they’ve clung to efforts there like the early morning mists that frequently envelop this rolling, red clay farmland.

July 24, 1964, was steamy hot — much like the election campaign that ended that day, with workers at Monroe voting whether to have the United Auto Workers union represent them or remain non-union.

The company was determined to keep the union out at all costs. It had moved its shock absorber assembly operations to Georgia from Michigan specifically to avoid UAW. Now the union threatened Monroe’s strategy of widening profit margins by running to an area where it could pay workers only $1.35 an hour instead of $3-plus.

As the National Labor Relations Board representative Scott Watson began to tally the votes that Thursday, the frowns etched across stone-faced Monroe execs gave way to grins. Their campaign of violence, intimidation, fear and reprisal had worked. It looked like a three-to-one victory for the company.

Even John Tate, the attorney who master-minded Monroe’s anti-union battle, broke into a rare smile as plant manager Charlie Gordon quietly passed the word to hand out the half-pints and beer to the workers on the second shift. By 12:50 a.m., when the union’s defeat (466-147) was formally announced, refreshments had provided the momentum for a planned march to the courthouse square. About 200 people gathered in front of the Hart County courthouse, milling around and blocking US Route 29, the main road then between Atlanta and Charlotte, N.C. The mood was surly, rather than jubilant. The group was no longer a crowd — it was a mob.

Shortly after 1 a.m., a company pickup truck drove up and a chunky, crew-cut boss with a tobacco chaw in his cheek dragged a life-like dummy toward a tree on the left side of the courthouse. Grinning, he yelled to the crowd: “C’mon boys, let’s string up Walter Reuther here and show these communists what’ll happen if they ever set foot in Hart County again.”

Moments later, the Reuther effigy dangled a foot or so off the ground, swaying slightly in the summer breeze. The mob cheered as a sign was draped around the limp neck: "Notice to all. Here hangs UAW. Caught trying to steal jobs from Monroe employees.”

Pistol shots cracked across the square and the dummy recoiled once, then again — six times finally and little dribbles of sawdust and cotton batting fell from the holes. More beer was passed around and more shots fired before the crowd began to drift away. As the man with the crew-cut climbed back into the pickup, he yelled to the stragglers, "Let’s go find us some real ones, boys, what d’ya say?”

I

Union organizers Lou Echols and Ralph Crawford were no strangers to violence. They were attacked a year earlier when they tried to leaflet the Monroe plant. The company shut down operations and ordered workers to run off the organizers.

A second effort to handbill the plant included UAW Vice President Pat Greathouse, Nick Zonarich and other top officials of the AFL-CIO’s Industrial Union Department. About 150 Monroe foremen and employees armed with crowbars and billy clubs ran the group off while local police looked on. One of the mob, now a UAW supporter, recalls "there were a lot of licks passed.” Greathouse, wearing a UAW t-shirt, was attacked. After the beatings, the organizers found their car tires slashed. The mob encircled the car and refused to allow it to be repaired, forcing the unionists to send a tow truck across state lines from South Carolina to rescue the car the next day.

Even though no one would rent a room to them, Echols and the other organizers kept coming back to Hartwell. "We’d stay in a little ol’ motel in Royston; that’s where Ty Cobb was born,” Echols remembers. "Monroe would send fellas who’d park their cars right in front of our room and shine their high beams on us all night and sling rocks against the side of the place hoping to run us off.”

They didn’t succeed.

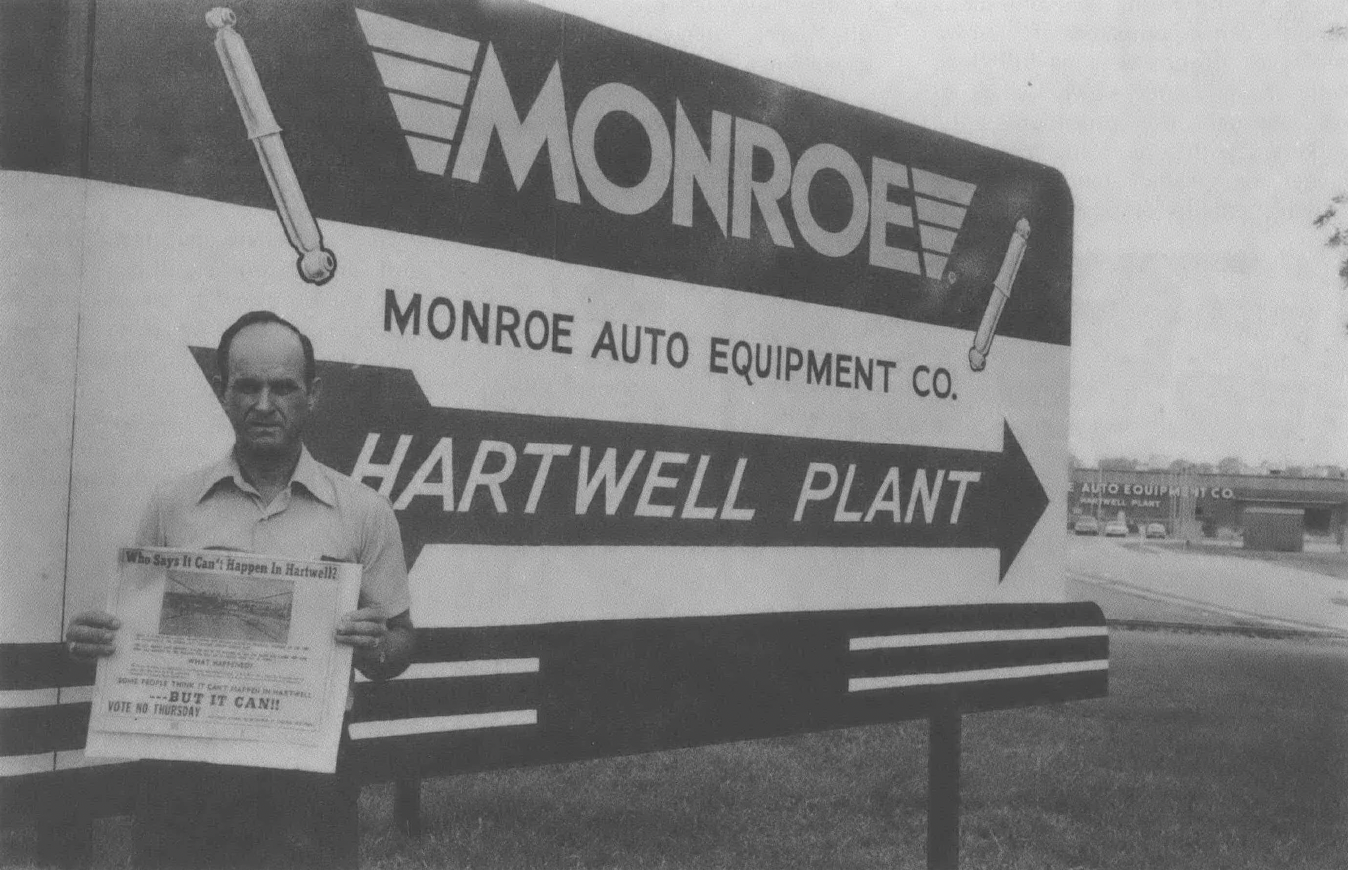

Eventually, enough workers at the Hartwell plant signed UAW cards, and the July 24 election was ordered by the NLRB. Threatened with the very element that initially caused them to move out of Michigan — the union and the higher wages and benefits it would bring — Monroe pulled out all the stops. Court records and interviews reveal the massive campaign of intimidation the company engaged in to fight the UAW. In addition to the violence, Monroe launched a propaganda campaign that in a more refined form, has become the chief weapon of union busting runaway shops across the South. Its centerpiece is the multipronged effort to convince workers that the plant would be forced to close and move elsewhere if it was unionized. In effect, choosing the union does not mean job security — it means unemployment.

Inside the factory Monroe hung huge banners covered with pictures of their Hillsdale, Michigan plant that had closed. Across the photo was a big X and the line: “It Can Happen Here.” The local newspaper carried articles "proving” that then UAW President Walter Reuther was a communist and that the union gave donations to the NAACP, the Jewish Labor Committee, the Americans for Democratic Action and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights. Local radio stations day after day echoed the theme as did many of the preachers in the predominantly fundamentalist area. A vote for the union was a vote against God, Jesus Christ, the Holy Ghost and everything sacred.

Monroe practiced its own brand of brotherly love within the plant, complete with widespread harassment and reprisals against workers who publicly indicated they believed a union contract might bring better working conditions and decent wages. Those favoring the union were frequently moved to the toughest, dirtiest jobs in the plant at lower pay.

In short, it was an outside shot that the Monroe workers would choose the union in the face of such a vicious and illegal campaign.

II

Lou Echols didn’t feel very excited about sticking around and engaging in small talk once the votes were tallied July 24th. He wondered why the National Labor Relations Board let the company set up the election so the ballots would be counted late at night.

"A lot of folks was feelin’ real strong about things because of the way the company had used the churches and the radio and all to make ’em think we was all communists who were going to steal their jobs,” he recalls. "Some of them was good people, but they’d been confused and misled. I knew when we heard the liquor was being passed out and they was getting ready to hang Walter Reuther at the courthouse that it was time to get on our way.”

Oddly, it was another act of violence that may have saved them. Several days before, nightriders shotgunned a black civil-rights worker traveling north on Highway 29. FBI agents visited the Monroe plant immediately prior to the elections seeking links between the slaying and the high-pitched mood the company’s hate campaign engendered.

While no links were found, the presence of FBI agents helped Echols and Crawford make arrangements for protection that night. ‘‘We took on off out of there fast,” Echols recalls. ‘‘We’d left two men back in Royston and I’d told them if we weren’t back by 1:30 a.m. to call the police and tell them there’d been a wreck on the highway between Royston and Hartwell. I told them to also report a fire there too so we’d maybe have a hope.

“Two cars pulled out after us and chased us about halfway, until state troopers we arranged through the federals and Gov. (Carl) Sanders blocked them off,” Echols says. “When we got to Royston, we found they’d beat up on the men we’d left there and run ’em off. I never felt so good as when we got out of there. If they just wanted to whip us, it wouldn’t have been so bad. I’ve been whipped a few times before, but that wasn’t what they had planned that night, no sir.”

The next day, the plant shut down at noon and about 500 people gathered in the courthouse square for a mock funeral. The effigy of Walter Reuther was cut down from the tree where it had dangled all night.

The local funeral home provided a pine coffin and, as women, children and workers looked on, Carey Thrasher, J.L. Herring and James Boleman placed the dummy in the coffin. Broughton Sanders, the Hart County Coroner, who also worked as a foreman at Monroe, took the microphone and informed the crowd that he as coroner had examined the body and found it to be legally dead.

The funeral hymn “Just One Rose” was sung and a wreath of pine and bitterweed placed on the coffin. The Monroe foremen covered it with sand and placed a grave marker atop the site:

Less (sic) we forget

Here Lies UAW

Born in Greed

Died in Defeat

July 23, 1964

Hartwell, Georgia

III

Indeed it did appear for the moment that the UAW was dead in Hartwell-murdered, in fact, by a massive, illegal campaign by Monroe Auto Equipment Co. The only real consolation was that despite the intimidation and physical violence over the 18 month campaign, no one had been killed.

In Detroit, top UAW officials realized that if Monroe’s strategy of running away to an area where it could pay workers half what it did in the North was successful, other companies would begin to do the same thing. Under the leadership of Vice President Pat Greathouse, the UAW and the IUD decided that although company goons had pronounced the union dead in Hartwell, it would, like Lazarus, rise again in health.

Lawyers Morgan Stanford, Joe Rauh, Steve Schlossberg, Dan Pollitt and others documented the numerous violations of the National Labor Relations Act committed by Monroe. Ultimately, the election results were set aside and a second election ordered. Unsure of its support, the UAW informed workers they would have to get cards signed on their own. Within three weeks, more than half of the workers signed cards asking that the UAW represent them.

“I guess we realized we’d done got taken,” says Eury Nannie, who has worked for Monroe 17 years. “For some folks this was their first job ever. They was farmers and kept on farming while they worked at the plant — this was the first time they ever seen a paycheck in their lives and they didn’t want to do anything to lose it. But while the company put a scare in people, that didn’t make ’em like the company much either. They saw the way people got mistreated and all. We’re country, but that don’t mean we ain’t smart.”

The second time around, in 1966, teams of UAW supporters — coalitions of blacks and whites, men and women — set about to debunk the company’s threats to close down and move away if the union got in. Their efforts paid off. The UAW won the representation election, 342-264. This time there was no hanging and no mock funeral. Workers expected to be enjoying the benefits of a union contract shortly — a contract that would give them job protection, a grievance procedure, seniority rights, decent pensions, health insurance and maybe even a wage increase that would get them back in the range of what Monroe workers in Michigan had been paid for doing the same work.

The workers were wrong. The battle had only begun with the election victory. For the next ten years, Monroe Auto Equipment ignored their employees’ desire by successfully evading the orders of the National Labor Relations Board and a variety of courts. The Labor Act, originally hailed as the “Magna Carta” for American workers, effectively protected the company from the workers by allowing them to stall efforts to get a contract to death. Like J.P. Stevens, Monroe used the law to make crime pay.

It began the day after the second election. On the election day, both the UAW and Monroe had certified that all ballots were counted. The cardboard box was torn up and the union declared the winner. But the next day, Monroe presented the ballot box, pasted back together with a ballot hanging out of it, and filed a protest claiming all ballots had not been counted.

The NLRB Regional Director found Monroe’s claims to be ludicrous and overruled them without a hearing. After months of maneuvering, the UAW was finally certified as bargaining agent for the Hartwell employees. But Monroe refused to bargain and continued to file a variety of appeals. Eventually, in I967, an NLRB trial examiner found Monroe guilty of refusing to bargain as required by the Labor Act.

Monroe continued its strategy of delay, appealing and losing in both the Fifth Circuit and the US Supreme Court. By then, some eight years had elapsed and Monroe had yet to bargain with the UAW. At the cost of some lawyers’ fees and little else, the company saved millions of dollars by evading a union contract over the eight-year period.

After more appeals with the NLRB, Monroe filed a new suit in district court asking for an injunction against the UAW and an order to the NLRB to hold a new election. It lost, but appealed to the Fifth Circuit again. Having seen the case for the third time, the Fifth Circuit judges strongly rebuked Monroe for refusing to obey the law. They assessed double costs and attorneys’ fees because the legal maneuvering by Monroe was so clearly just a delaying tactic to avoid the law and previous court rulings.

IV

Finally, in 1973, Monroe attorney John Tate agreed to begin bargaining. Not surprisingly, the company’s version of bargaining was to meet at a Ramada Inn conference room, listen to union proposals and respond with one word: “No.”

Among the proposals rejected were those as basic and simple as a dues check- off, any sickness or accident benefits, pensions, seniority protection, grievance procedure, health insurance or cost-of-living protection. “We’d ask this guy Tate why the company could provide those things for the remaining workers in Michigan who had all of them,” says Claude Pereira, who led the bargaining team. “What was good enough for those up North wasn’t good enough for us.”

Negotiations continued every six weeks or so and were often delayed because Tate, chief negotiator for Monroe, had been retained by Willie Farah to aid the clothing manufacturer in combatting the Amalgamated Clothing Workers unionizing efforts. As bargaining continued without results, frustrations grew among union supporters. “Those of us who grew up in the South were taught if you stole a penny, the federal government would spend a million to track you down and see justice done,” organizer Lou Echols says. “People can’t understand how Monroe could evade the law year after year after year. They lose faith in our system.”

Echols saw the company’s strategy saving management millions, while confusing employees who tired of hearing about legal actions. Uncertain that it could effectively prosecute a strike, the union turned to a boycott of Monroe products. But a high percentage of shock absorbers Monroe makes are sold under 20 or more brand names, making an effective consumer boycott quite difficult.

In November, 1975, a Texan named David Cox arrived in Hartwell and checked into the Ramada Inn. Soon Cox began to solicit union cards on behalf of an organization called the Allied Industrial Union of Auto Workers Independent. The group, with no constitution, no bylaws, and no collective bargaining agreements had never been recognized anywhere. Equipped with the complete mailing list observers believe was supplied by the company, Cox succeeded in getting enough cards to petition for an election. The campaign that followed proved to be, in many ways, a repeat of those of 10 and 12 years before — full of company threats and intimidation.

Tate, by this time a master campaigner against labor unions (now in wide demand for such services throughout the South), recycled old ads about how the company would have to shut down if it went union, just like the Hillsdale, Mich., facility. With the relatively high turnover since the UAW first won 10 years before, the old threats carried as good as new for many Monroe workers, particularly in view of the massive downturn in the economy, and in the auto industry in particular.

Although David Cox’s phony union received only 11 votes after he had been revealed as a former labor relations official for the Piggly Wiggly super market chain in Arlington, Texas, the UAW was defeated. The union, as might be expected, has filed a number of unfair labor practices that stand a good chance of ultimately winning an NLRB order overturning the election.

“We are back where we were the day they buried the UAW in the court house square” Lou Echols says. “I started trying to organize this plant back before President Kennedy was assassinated. My little girl hadn’t even started school and next week she’s graduating. It shouldn’t be so hard for workers to get the protection of a union contract no way.

“Something’s got to give if we have a deal where the guy who builds the shocks for that LTD makes only half of what the guy up North who puts ’em into the car. Either he’s got to come up, or the other guy’s gonna come down. I’d rather have him come up and that’s why I may be sitting in Hartwell talkin union til I’m 65 and they pension me off.”

V

What are the lessons of the Monroe story for rank-and-file workers, their labor unions, the South as a region and the country as a whole?

There are many, but among the most important needs are:

• a massive overhaul of the Labor Act to keep it from being the companies’ chief tool to repress workers.

• expanded union organizing strategies to deal with the increasing number of runaway shops.

• new legislation insuring a job for every person able to work.

• a major effort toward building an international labor movement.

• and a rededication to the crucial importance of union organizing in the South.

While proposals to repeal 14-B right-to-work provisions of Taft-Hartley have been kicking around for almost 30 years, the time has come for a massive effort by the labor movement for major reform in US labor law. Rather than an aside, it must be a central focus of a united labor movement.

Monroe, J.P. Stevens, Duke Power, Russell Stover and hundreds of other corporations today have economic incentives to violate the Labor Act. “It is widely known that it is more profitable to commit flagrant unfair labor practices to keep the union out rather than pay decent wages and benefits to workers,” UAW General Counsel Stephen Schlossberg told a House subcommittee considering proposed labor law reforms earlier this year.

What kind of changes should be made? Here are just a few that would make a good beginning:

1. Give workers the right to sue for triple damages those companies that violate the act. Few developments undercut union organizing more than winning a representation election and then being unable to deliver a contract. If a company refuses to bargain in good faith, the only remedy in virtually all cases is an NLRB or court order to bargain. Without stiff monetary penalities, companies have no real incentive to follow the order.

2. Workers dismissed for union activity should be allowed to bring private damage suits against employers who fire them. Discharges are frequently a key element in intimidating workers who support unionization; at the present, the remedy is only reinstatement and back pay. The law now makes it possible for employers to sue unions for losses that result from secondary boycotts, yet workers can’t sue employers for the loss of livelihood they suffer when discharged for union activity.

3. The Labor Act must be streamlined and the number of time-consuming loopholes that allow employers to delay for years must be limited. While employers are entitled to due process protections, the current protections they enjoy are so great that the purpose of the Labor Act is virtually nullified by them. To eliminate the worst loophole the decisions of administrative law judges should be enforceable immediately, rather than allowing them to be postponed by de novo review by the NLRB itself. In 1974, the Board ruled on 846 contested unfair labor practice cases against employers, and violations of the Act were found in 82 percent of those decisions — a record indicating requests are made by companies who don’t expect to win, but only to delay.

4. Companies that repeatedly commit unfair labor practices should be denied government contracts. Other legislation currently in effect, such as the Walsh Healy Act, provides similar types of penalties. Employers who have violated the minimum wage laws, for example, can be blacklisted for up to three years by the federal government.

5. Employers should be required to bargain with workers for a union contract on the basis of authorization cards showing a majority support the union as their representative. Before Taft Hartley, such a procedure was legal in the US and still exists in Canada. Such a procedure would reduce the company fear campaigns so prevalent in union representation elections.

6. The NLRB should seek court injunctions ordering dismissed workers to be reinstated while the Board is investigating and processing charges filed on their behalf. More than 2,000 unfair labor practice complaints were issued against employers in fiscal 1973 and many of those involved such dismissals. Yet the NLRB sought federal court orders restraining the unlawful conduct of these companies only five times, while it sought similar injunctions against unions hundreds of times that same year.

7. Provisions limiting secondary boycotts and hot cargo restrictions should be repealed. Although it is unlikely that Congress will give unions secondary boycott and hot cargo rights, the growing centralization of corporate power and growth of multinationals that act above the law make it necessary to give labor new rights to partially balance that new corporate power. Repeal of the limits on secondary boycotts would make it possible for other unions to pursue boycotts similar to those conducted effectively by the farmworkers in the UFW (who are not covered by the federal legislation). If the UAW and the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers could boycott, for example, J.C. Penney’s for handling Monroe Shock Absorbers and J.P. Stevens sheets, a great new weapon would exist.

Similarly, if the so-called hot cargo limitations of the law were lifted, UAW workers in Ford assembly plants in Detroit could support Southern organizing efforts by refusing to handle Monroe shock absorbers. Workers in other countries, such as Great Britain, have the right to refuse to handle non-union or struck goods.

8. All state right-to-work laws should be repealed. Compulsory open shop laws still give workers, particularly in the South, the “right” to work for less. Repeal of 14-B of Taft-Hartley is long overdue. The labor movement must put some vigor into this effort again. The efforts of the AFL-CIO and UAW in Arkansas are an example of growing new interest in eliminating right-to-work (for less) laws.

Although reform of labor law is crucial, there are a number of other areas of legislation that would greatly aid efforts to organize, particularly in the South. Most important are efforts to control runaway shops, such as Monroe. As long as the current economic system exists, corporations will always seek out areas in which they can produce their products at the lowest wages and with the fewest restrictions on so-called “management prerogatives.’’ Major companies, such as General Motors (see box), have made significant corporate decisions at the highest levels to open new plants in the South and attempt to keep those plants non-union. Such developments threaten the very existence of the labor movement today. The best remedy, as UAW President Leonard Woodcock noted recently, is to organize them. But what else must be done?

• One major need is for legislation providing workers with new rights and corporations with new restrictions in cases of plant closures and relocations. Very simply, plant relocations affect too many people to be left to a narrow cadre of jet-lagged, alcohol-soaked corporate executives who seldom live in the areas devastated by their decisions.

Most other western industrial countries have recognized this fact and have put some controls on runaway plants. In Britain, for example, a company desiring to relocate or close a factory must be authorized to do so by the government. West Germany, France, and the Netherlands require government approval prior to relocation of plants — and they require advance approval even for layoffs. Japan has virtually eliminated the problem of unemployment due to plant relocation by guaranteeing the worker a lifetime job.

In the US, courts have held that corporations such as Monroe are free to sign labor contracts and then abrogate them merely by deciding to shut down their operations and move elsewhere. When a union signs an agreement, however, it is obligated to live by it until it expires.

American workers and their unions must wage a priority fight for legislation that would make at least minimum requirements on companies that want to relocate. Employees should be entitled at least to notice, major severance allowance, transfer rights and pension protection. Companies should be required to get permission from the Sec. of Labor before relocating, and if the Secretary finds that the primary reason for relocating is to exploit cheap labor markets, then permission should be denied — as it should be if the move would adversely affect employment in the area left behind.

• Another important check on the runaway shop is the control of local grants and various tax concessions to new industry. Frequently, as in the case of Hart County and the Monroe plant there, a local unit of government will offer to build the new plant and lease it back to the company. Railroad spurs, access roads and sewage treatment may also be provided by the taxpayers. The community residents who have the “opportunity” to work at wages 25-40 percent lower than those paid elsewhere, thus also get to subsidize the company that profits from their labor. Major restrictions should be placed on such public giveaways, aimed at limiting the degree to which workers and community residents pay for corporate profitmaking on the part of rogue employers such as Monroe.

• Another need is for the federalization of many key social benefits, such as unemployment compensation, welfare and workers’ compensation. Allowing states to operate at substandard levels, a particularly prevalent practice in many Southern states, provides an added incentive for corporations to relocate in the South. And it makes possible economic blackmail, with corporations like General Motors stopping construction of a new facility in Michigan until the state legislature refused passage of improvements in workers’ compensation.

• Still another key piece of legislation — the Hawkins-Humphrey bill — would strengthen Southern organizing efforts by ordering the federal government to take steps to insure that every person able and willing to work will have a job, at no less than the minimum wage. In cases like Monroe, where the company came South and paid only a nickel over the minimum wage, the impetus to vote against the union to save local jobs would have been greatly reduced.

• Finally, the labor movement must quickly expand its international scope. In this era of multinationals, companies also have little difficulty seeking low-wage areas in other countries. As the South becomes organized, it too will face the problem of runaway shops. Monroe Auto Equipment still produces most of its products in non-union plants here, but in June it imported a major shipment of assembled shock absorbers from Onner de Brazil, S.A. and MAP Auto Pecas, S.A. — two Brazilian companies it recently purchased. Monroe also recently bought interests in plants in Mexico and Venezuela and acquired a wholly-owned subsidiary in Argentina.

Efforts must be made to achieve multinational cooperation and solidarity between labor unions, which might seek coordinated bargaining, common contract expiration dates and information exchanges. The UAW, for example, has been instrumental in the efforts to raise wages and improve working conditions both in Europe and Japan through the International Metalworkers Federation.

VII

Given the current conservative mood of the country, many of the legislative goals Southern workers and their Northern counterparts are fighting for may not be achieved in the near future. And workers have known for years that even well-intended legislation often is subverted and reoriented by corporate interests and their many friends in and out of government. The Labor Act is but one example.

While that’s no reason to quit the fight, it must be waged in many other arenas. The most crucial is a rededication by the labor movement to organizing in the South. As population and plants shift South, labor unions must organize or their power will be severely eroded. Southern organizing cannot be regarded as a futile luxury. The very future of the labor movement is at stake.

The J.P. Stevens campaign appears to be a sign of new interest in Southern organizing by the AFL CIO. Moves by General Motors and other auto-related companies to the South also promise to elicit massive efforts by the UAW there. Other unions, such as the United Electrical Workers, have recently and successfully followed runaways South and organized them in places like Tampa and Charleston.

New kinds of coalitions must be created between unions and others with community power — the churches, environmental groups, local media outlets, civil rights activists and elected officials — if the Southern organizing challenge is to be met.

Like the UAW’s fight at Monroe, it must be viewed as a long term struggle — one that may take years and years and still not be over.

Corporations, with their tremendous power, will continue to use violence, threats, intimidation, race, sex, politics and everything else at their disposal to break the union movement in the South. But they won’t succeed.

Not as long as there are men like Lou Echols.

VI

Echols goes back now to Hartwell about once a week to meet with union supporters. There’s a nice freeway now (US 85) instead of the old road company goons chased him down after hanging Walter Reuther in effigy.

He’s got a CB radio that provides some diversion on the trips he and UAW Rep. Claude Pereria make. The new Ramada Inn will rent him a room now, unlike the old days when he couldn’t get one in Hartwell and had to drive to Ty Cobb’s hometown of Royston.

He still makes house calls with pro-union Monroe workers, attempting to convince new workers and old recalcitrants that folks would be better off with a union contract. Many of the kids he’d see on similar efforts in the ’60s now have grown up and gone to work in the plant.

“We’re gonna bring the UAW to Monroe here in Hartwell,” Echols says. “If a little ol’ company like Monroe can beat the UAW and can get away with treating people the way it does, then our country’s in real trouble.”

Echols, angry but still somehow reserved, gazes out the window as the Lavonia sheriff drives up and down outside his room every 15 minutes, something he does from about half an hour after UAW people check in until they leave.

“I don’t know how long it’ll take us — I’ve seen four Presidents come and go while I been sittin’ down here fighting this fight. But the people here in Hartwell are going to bring the union to Monroe, they sure are.”

Somehow, listening to Lou Echols, you know he has to be right.

Tags

Don Stillman

Don Stillman is the editor of Solidarity, the United Auto Workers 1. 7 million-circulation magazine. (1976)